NIH Public Access Author Manuscript Drug Alcohol Depend

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

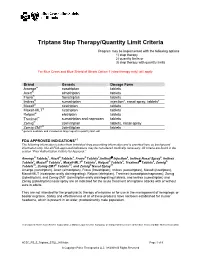

Triptans Step Therapy/Quantity Limit Criteria

Triptans Step Therapy/Quantity Limit Criteria Program may be implemented with the following options 1) step therapy 2) quantity limits or 3) step therapy with quantity limits For Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Illinois Option 1 (step therapy only) will apply. Brand Generic Dosage Form Amerge® naratriptan tablets Axert® almotriptan tablets Frova® frovatriptan tablets Imitrex® sumatriptan injection*, nasal spray, tablets* Maxalt® rizatriptan tablets Maxalt-MLT® rizatriptan tablets Relpax® eletriptan tablets Treximet™ sumatriptan and naproxen tablets Zomig® zolmitriptan tablets, nasal spray Zomig-ZMT® zolmitriptan tablets * generic available and included as target agent in quantity limit edit FDA APPROVED INDICATIONS1-7 The following information is taken from individual drug prescribing information and is provided here as background information only. Not all FDA-approved indications may be considered medically necessary. All criteria are found in the section “Prior Authorization Criteria for Approval.” Amerge® Tablets1, Axert® Tablets2, Frova® Tablets3,Imitrex® injection4, Imitrex Nasal Spray5, Imitrex Tablets6, Maxalt® Tablets7, Maxalt-MLT® Tablets7, Relpax® Tablets8, Treximet™ Tablets9, Zomig® Tablets10, Zomig-ZMT® Tablets10, and Zomig® Nasal Spray11 Amerge (naratriptan), Axert (almotriptan), Frova (frovatriptan), Imitrex (sumatriptan), Maxalt (rizatriptan), Maxalt-MLT (rizatriptan orally disintegrating), Relpax (eletriptan), Treximet (sumatriptan/naproxen), Zomig (zolmitriptan), and Zomig-ZMT (zolmitriptan orally disintegrating) tablets, and Imitrex (sumatriptan) and Zomig (zolmitriptan) nasal spray are all indicated for the acute treatment of migraine attacks with or without aura in adults. They are not intended for the prophylactic therapy of migraine or for use in the management of hemiplegic or basilar migraine. Safety and effectiveness of all of these products have not been established for cluster headache, which is present in an older, predominantly male population. -

Medication Guide 2012

DeKalb County D.U.I. Court Supervised Treatment Program MEDICATION GUIDE Medication Guide 2012 DeKalb County State Court Decatur, Georgia xxi ********** WELCOME TO THE DEKALB COUNTY D.U.I. COURT SUPERVISED TREATMENT PROGRAM. This 2012 Medication Guide was developed as a collaborative effort by Becky Pirouz, Pharm.D., Director of Pharmacy, Peachford Hospital, and by Lois Michalove, Treatment Coordinator for the DeKalb County D.U.I. Court Supervised Treatment Program, both of whom have extensive experience in addiction recovery and treatment. ********** The following information is intended to assist you in making decisions about medications. This may include those medications that you are prescribed and/or your selection of over-the-counter (OTC) products. Unintended exposure may compromise your treatment program. This is not an exhaustive list, but contains some of the medications that are most commonly used. If in doubt, always consult the Treatment Coordinator. Please inform your physician, dentist, pharmacist and other health care professionals that you are in a recovery program. WE ARE A ZERO-TOLERANCE PROGRAM! DO NOT COMPROMISE YOUR RECOVERY BY MAKING HIGH-RISK CHOICES! xxii - Section 1 – Drugs To Avoid The following drugs must not be used at any time. They are well known to be abused and even small amounts may result in relapse and are contraindicated in your treatment program. However, extenuating circumstances may occur which necessitates the short- term limited use of some of the drugs on this list in consultation with your physician, the Judge and the Treatment Coordinator. This decision should be made prior to your ingestion of any of the Drugs to Avoid. -

Guideline for Preoperative Medication Management

Guideline: Preoperative Medication Management Guideline for Preoperative Medication Management Purpose of Guideline: To provide guidance to physicians, advanced practice providers (APPs), pharmacists, and nurses regarding medication management in the preoperative setting. Background: Appropriate perioperative medication management is essential to ensure positive surgical outcomes and prevent medication misadventures.1 Results from a prospective analysis of 1,025 patients admitted to a general surgical unit concluded that patients on at least one medication for a chronic disease are 2.7 times more likely to experience surgical complications compared with those not taking any medications. As the aging population requires more medication use and the availability of various nonprescription medications continues to increase, so does the risk of polypharmacy and the need for perioperative medication guidance.2 There are no well-designed trials to support evidence-based recommendations for perioperative medication management; however, general principles and best practice approaches are available. General considerations for perioperative medication management include a thorough medication history, understanding of the medication pharmacokinetics and potential for withdrawal symptoms, understanding the risks associated with the surgical procedure and the risks of medication discontinuation based on the intended indication. Clinical judgement must be exercised, especially if medication pharmacokinetics are not predictable or there are significant risks associated with inappropriate medication withdrawal (eg, tolerance) or continuation (eg, postsurgical infection).2 Clinical Assessment: Prior to instructing the patient on preoperative medication management, completion of a thorough medication history is recommended – including all information on prescription medications, over-the-counter medications, “as needed” medications, vitamins, supplements, and herbal medications. Allergies should also be verified and documented. -

UCSF UC San Francisco Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCSF UC San Francisco Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Deep phenotypic profiling of neuroactive drugs in larval zebrafish Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3vk1d0gr Author Gendelev, Leo Publication Date 2019 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Deep phenotypic profiling of neuro-active drugs in larval Zebrafish by Lev Gendelev DISSERTATION Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Biophysics in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN FRANCISCO Approved: ______________________________________________________________________________Michael Keiser Chair ______________________________________________________________________________DAVID KOKEL ______________________________________________________________________________Jim Wells ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ Committee Members Copyright 2019 by Lev (Leo) Gendelev ii In Loving Memory of My Mother, Lucy Gendelev iii Acknowledgements First of all, I thank my advisor, Michael Keiser, for his unwavering support through the most difficult of times. I will above all else reminisce over our brainstorming sessions, where my half- wrought white-board scribbles were met with enthusiasm and sometimes even developed into exciting side-projects. My PhD experience felt less like work and more like a fantastical scientific -

Triptan Therapy for Acute Migraine

Triptan Therapy for Acute Migraine Headache John Farr Rothrock, MD University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL Deborah I. Friedman, MD, MPH University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas, TX The “triptans” are 5HT-1B/1D receptor agonists that were developed to treat acute migraine and acute cluster headache. Sumatriptan, the original triptan preparation, has been in general use since 1993, so there has been considerable experience with triptans over time. There are currently seven oral triptans on the market in the United States: sumatriptan (Imitrex™), naratriptan (Amerge™), zolmitriptan (Zomig™), rizatriptan (Maxalt™), almotriptan (Axert™), frovatriptan (Frova™), and eletriptan (Relpax™); brand names may differ by country. There is also a combination preparation of oral sumatriptan/naproxen (Treximet™). Two triptans (sumatriptan, zolmitriptan) are marketed as nasal sprays, and sumatriptan is available for subcutaneous injection, including a needle-free subcutaneous delivery system (Sumavel™). Sumatriptan suppositories are marketed in Europe but not in North America. Zolmitriptan and rizatriptan are sold in an oral disintegrating tablet or “melt” formulation as well as in tablet form; while the “melt” formulations may be more convenient (no liquid is required to propel them into the stomach), they are absorbed similarly to regular tablets and there is no evidence to suggest that they work faster than the tablet formulations. Some patients with migraine-associated nausea prefer the disintegrating tablets while others cannot tolerate their taste. Although all of the triptans initially were investigated for the treatment of migraine headache of moderate to severe intensity and were superior to placebo in those pivotal trials, they appear to be more consistently effective when used to treat migraine earlier in the attack, when the headache is still mild to moderate. -

Engineered Cells for Production of Indole-Derivatives

Downloaded from orbit.dtu.dk on: Oct 05, 2021 Engineered cells for production of indole-derivatives Kell, Douglas; Yang, Lei; Malla, Sailesh Publication date: 2020 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link back to DTU Orbit Citation (APA): Kell, D., Yang, L., & Malla, S. (2020). Engineered cells for production of indole-derivatives. (Patent No. WO2020187739). General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. ) ( 2 (51) International Patent Classification: C07K 14/715 (2006.01) (21) International Application Number: PCT/EP2020/056828 (22) International Filing Date: 13 March 2020 (13.03.2020) (25) Filing Language: English (26) Publication Language: English (30) Priority Data: 19163 184.5 15 March 2019 (15.03.2019) EP (71) Applicant: DANMARKS TEKNISKE UNIVERSITET [DK/DK]; Anker Engelunds Vej 101 A, 2800 Kgs. Lyngby (DK). (72) Inventors: KELL, Douglas, Bruce; Chirk Manor, Trevor Rd, Chirk, Wrexham LL14 5HD (GB). -

Recreational Use, Analysis and Toxicity of Tryptamines

Send Orders for Reprints to [email protected] 26 Current Neuropharmacology, 2015, 13, 26-46 Recreational Use, Analysis and Toxicity of Tryptamines Roberta Tittarelli1, Giulio Mannocchi1, Flaminia Pantano1 and Francesco Saverio Romolo1,2,* 1Legal Medicine Section, Department of Anatomical, Histological, Forensic Medicine and Orthopedic Sciences, “Sapienza” University of Rome, Viale Regina Elena, 336, 00161 Rome, Italy; 2Institut de Police Scientifique, Université de Lausanne, Batochime, 1015 Lausanne, Switzerland Abstract: The definition New psychoactive substances (NPS) refers to emerging drugs whose chemical structures are similar to other psychoactive compounds but not identical, representing a “legal” alternative to internationally controlled drugs. There are many categories of NPS, such as synthetic cannabinoids, synthetic cathinones, phenylethylamines, piperazines, ketamine derivatives and tryptamines. Tryptamines are naturally occurring compounds, which can derive from the amino acid tryptophan by several biosynthetic pathways: their structure is a combination of a benzene ring Roberta Tittarelli and a pyrrole ring, with the addition of a 2-carbon side chain. Tryptamines include serotonin and melatonin as well as other compounds known for their hallucinogenic properties, such as psilocybin in ‘Magic mushrooms’ and dimethyltryptamine (DMT) in Ayahuasca brews. Aim: To review the scientific literature regarding tryptamines and their derivatives, providing a summary of all the available information about the structure of these compounds, their effects in relationship with the routes of administration, their pharmacology and toxicity, including articles reporting cases of death related to intake of these substances. Methods: A comprehensive review of the published scientific literature was performed, using also non peer-reviewed information sources, such as books, government publications and drug user web fora. -

Triptans in the Treatment of Migraine in Adults

The role of triptans in the treatment of migraine in adults 28 Paracetamol or a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) can be used first-line for pain relief in acute migraine. A triptan can then be trialled if this was not successful. Combination treatment with a triptan and paracetamol or NSAID may be required for some patients. Most triptans are similarly effective, so choice is usually based on formulation, e.g. a non-oral preparation may be more suitable for patients with nausea or vomiting. To avoid medication overuse headache, triptan use should not exceed ten or more days per month. Migraine is a condition characterised by attacks of moderate A stepwise approach to managing migraine: to severe, throbbing headache, which is usually unilateral. This triptans are appropriate at step two is often associated with other symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, photophobia or phonophobia. Approximately one- There are a number of treatment guidelines for acute migraine, third of patients with migraines also experience a preceding all of which differ slightly in their recommended approach (see aura. Worldwide, approximately one in every seven people the NICE and BASH guidelines).3, 4 Most algorithms, however, are affected by migraines, which are often associated with recommend stepwise treatment, with triptans usually tried significant personal and socioeconomic impact.1 In the Global after paracetamol and NSAIDs. Burden of Disease Survey 2010, migraine was ranked as the third most prevalent disorder and the seventh-highest specific A reasonable approach is: 2 cause of disability. Step 1: Over-the-counter analgesics (paracetamol, NSAIDs) Step 2: Triptan For information on diagnosing migraine, see: Step 3: Combination treatment with a triptan and an NSAID National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) +/- anti-emetic (prochlorperazine, metoclopramide) at Guideline: Headaches. -

Cyclisation of Indoles by Using Orthophosphoric Acid in Sumatriptan and Rizatriptan

Available online www.jocpr.com Journal of Chemical and Pharmaceutical Research, 2013, 5(8):107-109 ISSN : 0975-7384 Research Article CODEN(USA) : JCPRC5 Cyclisation of indoles by using orthophosphoric acid in sumatriptan and rizatriptan K. Sudarshan Rao, K. Nageswara Rao, Bhausaheb Chavan, P. Muralikrishna and A. Jayashree Centre for Chemical Sciences and Technology, IST, Jawaharlal Nehru Technological University, Kukatpally, Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh, India _____________________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT A simple and Novel improved process for the preparation of pure Sumatriptan and Rizatriptan, the cyclisation of indole ring by the using of ortho phosphoric acid. The present work describes the detection, origin, synthesis, characterization and providing a commercial method to synthesize Sumatriptan and Rizatriptan. The procedure developed has several advantages such as mild reaction conditions, convenient operations and easily obtained materials. The synthetic method is suitable for industrial manufacture. Keywords: Cyclisation, Sumatriptan, Rizatriptan, ortho phosphoric acid, _____________________________________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION Triptans are a family of tryptamine-based drugs used as abortive medication in the treatment of migraines and cluster headaches. They were first introduced in the 1990s. While effective at treating individual headaches, they do not provide preventative treatment and are not considered a cure. The first triptan (i.e., tryptamine derivative) to be marketed for the acute treatment of migraine, sumatriptan, has been so successful that a number of second generation triptans are now marketed or in the late stages of clinical development 1,2 . The triptans represent a breakthrough in acute migraine treatment, being far more selective for 5-HT1B-1D receptors than their relatively nonselective predecessor’s ergotamine and dihydroergotamine (DHE) 3,4 . -

Download Leaflet View the Patient Leaflet in PDF Format

Package leaflet: Information for the user MAXALT® 10 mg Tablets/5 mg Tablets rizatriptan Read all of this leaflet carefully before you start taking this medicine because it contains important information for you. Keep this leaflet. You may need to read it again. If you have further questions, ask your doctor or pharmacist. This medicine has been prescribed for you only. Do not pass it on to others. It may harm them, even if their signs of illness are the same as yours. If you get any side effects, talk to your doctor or pharmacist. This includes any possible side effects not listed in this leaflet. See section 4. What is in this leaflet 1. What MAXALT is and what it is used for 2. What you need to know before you take MAXALT 3. How to take MAXALT 4. Possible side effects 5. How to store MAXALT 6. Contents of the pack and other information 1. What MAXALT is and what it is used for MAXALT belongs to a class of medicines called selective serotonin 5-HT1B/1D receptor agonists. MAXALT is used to treat the headache phase of the migraine attack in adults. Treatment with MAXALT: Reduces swelling of blood vessels surrounding the brain. This swelling results in the headache pain of a migraine attack. 2. What you need to know before you take MAXALT Do not take MAXALT if: you are allergic to rizatriptan benzoate or any of the other ingredients of this medicine (listed in section 6) you have moderately severe or severe high blood pressure or mild high blood pressure that is not controlled by medication you have or have ever had heart problems -

MAXALT® (Max-Awlt) and MAXALT-MLT® Rizatriptan Benzoate Tablets and Orally Disintegrating Tablets

Patient Information MAXALT® (max-awlt) and MAXALT-MLT® rizatriptan benzoate Tablets and Orally Disintegrating Tablets Read this Patient Information before you start taking MAXALT® and each time you get a refill. There may be new information. This information does not take the place of talking to your doctor about your medical condition or your treatment. Unless otherwise stated, the information in this Patient Information leaflet applies to both MAXALT Tablets and to MAXALT-MLT® Orally Disintegrating Tablets. What is MAXALT? MAXALT is a prescription medicine that belongs to a class of medicines called Triptans. MAXALT is available as a traditional tablet (MAXALT) and as an orally disintegrating tablet (MAXALT-MLT). MAXALT and MAXALT-MLT are used to treat migraine attacks with or without aura in adults and in children 6 to 17 years of age. MAXALT is not to be used to prevent migraine attacks. MAXALT is not for the treatment of hemiplegic or basilar migraines. It is not known if MAXALT is safe and effective for the treatment of cluster headaches. It is not known if taking more than 1 dose of MAXALT in 24 hours is safe and effective in children 6 to 17 years of age. It is not known if MAXALT is safe and effective in children under 6 years of age. Who should not take MAXALT? Do not take MAXALT if you: have or have had heart problems have or have had a stroke or a transient ischemic attack (TIA) have or have had blood vessel problems including ischemic bowel disease have uncontrolled high blood pressure have taken other Triptan medicines in the last 24 hours have taken ergot-containing medicines in the last 24 hours have hemiplegic or basilar migraines take monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitor or have taken a MAO inhibitor within the last 2 weeks are allergic to rizatriptan benzoate or any of the ingredients in MAXALT. -

Medication-Guide.Pdf

Migraine Medication Guide Migraine Medication Guide PREVENTIVE MEDICINES PREVENTIVE MEDICINES Dosing is intended for adults Dosing is intended for adults Migraine Prophylaxis: Level A Pediatric Migraine divalproex/sodium valproate* 500-1000 mg /day Intervention metoprolol 47.5-200 mg/day Analgesics: acetominophen, ibuprofen propranolol* 120-240 mg/day Triptans - FDA approved age 6-17 rizatriptan - weight <40kg (88 lbs), use 5 mg; (candesartan 8-16 mg/day) >40kg (88 lbs) use 10 mg timolol* 10-15 mg/day age 12-17 almotriptan- 6.25-12.5mg PO x1; Max 25/24h; may topiramate* 25-200 mg/day repeat dose x1 after 2h sumatriptan-naproxen sodium 10/60 tab; Max Migraine Prophylaxis: Level B 85/500mg tab per 24h zolmitriptan nasal spray (when nausea or vomiting) - riboavin (vitamin B2) 400 mg/day one 2.5 dose only Off-label use sumatriptan- 25 mg magnesium trimagnesium dicitrate 500-600 mg/day nasal sumatriptan - 5, 10, 25 mg feverfew 50-300 mg q12 zolmitriptan tab and melt tab - 5mg feverfew CO2 extract 2.08-18.75 mg q8 amitriptyline 25-150 mg/day (see below) Menstrual atenolol 100 mg/day (50-200 mg) no FDA approved therapies venlafaxine (ER) -Effexor 150 mg/day (37.5-150 mg) Mild-Moderate symptoms lisinopril 10 mg/day ibuprofen 800 mg every 8-12 hours prn histamine 1-10 mg subc 2x week naproxen 250 mg 1-2 every 8-12 hours prn fenoprofen 200 - 600 mg/day 500 mg every 12 hours prn acetaminophen, aspirin or ibuprofen with or without caffeine ibuprofen 200 mg q12 ketoprofen 50 mg q8 Moderate-Severe symptoms naproxen 500 - 1000 mg/day triptan with or