Treating Migraines in Patients with Psychiatric Disorders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ayahuasca: Spiritual Pharmacology & Drug Interactions

Ayahuasca: Spiritual Pharmacology & Drug Interactions BENJAMIN MALCOLM, PHARMD, MPH [email protected] MARCH 28 TH 2017 AWARE PROJECT Can Science be Spiritual? “Science is not only compatible with spirituality; it is a profound source of spirituality. When we recognize our place in an immensity of light years and in the passage of ages, when we grasp the intricacy, beauty and subtlety of life, then that soaring feeling, that sense of elation and humility combined, is surely spiritual. The notion that science and spirituality are somehow mutually exclusive does a disservice to both.” – Carl Sagan Disclosures & Disclaimers No conflicts of interest to disclose – I don’t get paid by pharma and have no potential to profit directly from ayahuasca This presentation is for information purposes only, none of the information presented should be used in replacement of medical advice or be considered medical advice This presentation is not an endorsement of illicit activity Presentation Outline & Objectives Describe what is known regarding ayahuasca’s pharmacology Outline adverse food and drug combinations with ayahuasca as well as strategies for risk management Provide an overview of spiritual pharmacology and current clinical data supporting potential of ayahuasca for treatment of mental illness Pharmacology Terms Drug ◦ Term used synonymously with substance or medicine in this presentation and in pharmacology ◦ No offense intended if I call your medicine or madre a drug! Bioavailability ◦ The amount of a drug that enters the body and is able to have an active effect ◦ Route specific: bioavailability is different between oral, intranasal, inhalation (smoked), and injected routes of administration (IV, IM, SC) Half-life (T ½) ◦ The amount of time it takes the body to metabolize/eliminate 50% of a drug ◦ E.g. -

The Migraine Attack As a Homeostatic, Neuroprotective Response to Brain Oxidative Stress: Preliminary Evidence for a Theory

ISSN 0017-8748 Headache doi: 10.1111/head.13214 VC 2017 American Headache Society Published by Wiley Periodicals, Inc. Views and Perspectives The Migraine Attack as a Homeostatic, Neuroprotective Response to Brain Oxidative Stress: Preliminary Evidence for a Theory Jonathan M. Borkum, PhD Background.—Previous research has suggested that migraineurs show higher levels of oxidative stress (lipid peroxides) between migraine attacks and that migraine triggers may further increase brain oxidative stress. Oxidative stress is trans- duced into a neural signal by the TRPA1 ion channel on meningeal pain receptors, eliciting neurogenic inflammation, a key event in migraine. Thus, migraines may be a response to brain oxidative stress. Results.—In this article, a number of migraine components are considered: cortical spreading depression, platelet acti- vation, plasma protein extravasation, endothelial nitric oxide synthesis, and the release of serotonin, substance P, calcitonin gene-related peptide, and brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Evidence is presented from in vitro research and animal and human studies of ischemia suggesting that each component has neuroprotective functions, decreasing oxidant production, upregulating antioxidant enzymes, stimulating neurogenesis, preventing apoptosis, facilitating mitochondrial biogenesis, and/or releasing growth factors in the brain. Feedback loops between these components are described. Limitations and challenges to the model are discussed. Conclusions.—The theory is presented that migraines are an integrated -

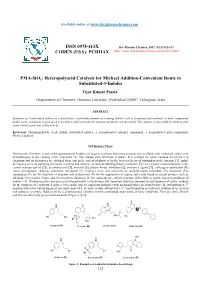

PMA-Sio2: Heteropolyacid Catalysis for Michael Addition-Convenient Route to Substituted-3-Indoles

Available online at www.derpharmachemica.com ISSN 0975-413X Der Pharma Chemica, 2017, 9(13):112-117 CODEN (USA): PCHHAX (http://www.derpharmachemica.com/archive.html) PMA-SiO2: Heteropolyacid Catalysis for Michael Addition-Convenient Route to Substituted-3-Indoles Vijay Kumar Pasala* Deapartment of Chemistry, Osmania University, Hyderabad-500007, Telangana, India ABSTRACT Synthesis of 3-substituted indoles in a hassel-free, ecofriendly manner by treating indoles with α, β-unsaturated carbonyl or nitro compounds under acidic conditions to give good to excellent yields with shorter reaction durations are described. The catalyst is recyclable for three to four times without great loss in the activity. Keywords: Phosphomolybdic Acid (PMA), Substituted indoles, α, β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds, α, β-unsaturated nitro compounds, Michael addition INTRODUCTION Heterocyclic chemistry is one of the quintessential branches of organic synthesis beaconing towards new scaffolds with medicinal values, new methodologies to the existing active principles etc. One among such skeletons is indole. It is perhaps the most common heterocycles in chemistry and its derivatives are obtained from coal pitch, variety of plants or by the bacterial decay of tryptophan in the intestine [1]. Indole derivatives serve as signaling chemicals in plants and animals, as nucleus building blocks (serotonin [2] (A) a crucial neurotransmitter in the central nervous system [3]), as antibacterial [4], antiviral [5], protein kinase inhibitors [6], anticancer agents [7], entheogens (psilocybin (B) causes perceptional changes), hormones (melatonin (C) regulates sleep and wakefulness), antidepressants (roxindole (D), bufotenin (E)), sumatriptan (F) for the treatment of migraine and ondansetron (G) for the suppression of nausea and vastly found in natural products such as alkaloids (Corynanthe, Iboga, and Aspidosperma alkaloids) [8-10], indigoids etc., which originate, either fully or partly, from bio-oxidation of indoles [11]. -

Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics and Drug

pharmaceutics Review Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics and Drug–Drug Interactions of New Anti-Migraine Drugs—Lasmiditan, Gepants, and Calcitonin-Gene-Related Peptide (CGRP) Receptor Monoclonal Antibodies Danuta Szkutnik-Fiedler Department of Clinical Pharmacy and Biopharmacy, Pozna´nUniversity of Medical Sciences, Sw.´ Marii Magdaleny 14 St., 61-861 Pozna´n,Poland; [email protected] Received: 28 October 2020; Accepted: 30 November 2020; Published: 3 December 2020 Abstract: In the last few years, there have been significant advances in migraine management and prevention. Lasmiditan, ubrogepant, rimegepant and monoclonal antibodies (erenumab, fremanezumab, galcanezumab, and eptinezumab) are new drugs that were launched on the US pharmaceutical market; some of them also in Europe. This publication reviews the available worldwide references on the safety of these anti-migraine drugs with a focus on the possible drug–drug (DDI) or drug–food interactions. As is known, bioavailability of a drug and, hence, its pharmacological efficacy depend on its pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, which may be altered by drug interactions. This paper discusses the interactions of gepants and lasmiditan with, i.a., serotonergic drugs, CYP3A4 inhibitors, and inducers or breast cancer resistant protein (BCRP) and P-glycoprotein (P-gp) inhibitors. In the case of monoclonal antibodies, the issue of pharmacodynamic interactions related to the modulation of the immune system functions was addressed. It also focuses on the effect of monoclonal antibodies on expression of class Fc gamma receptors (FcγR). Keywords: migraine; lasmiditan; gepants; monoclonal antibodies; drug–drug interactions 1. Introduction Migraine is a chronic neurological disorder characterized by a repetitive, usually unilateral, pulsating headache with attacks typically lasting from 4 to 72 h. -

Loss of Taste and Smell After Brain Injury

Loss of taste and smell after brain injury Introduction Following a brain injury many people report that their senses of taste and/or smell have been affected. This may be as a consequence of injury to the nasal passages, damage to the nerves in the nose and mouth, or to areas of the brain itself. Loss or changes to smell and taste are particularly common after severe brain injury or stroke and, if the effects are due to damage to the brain itself, recovery is rare. The effects are also often reported after minor head injuries and recovery in these cases is more common. If recovery does occur, it is usually within a few months of the injury and recovery after more than two years is rare. Sadly, there are no treatments available for loss of taste and smell, so this factsheet is designed to provide practical suggestions on how you can compensate. It provides information on health, safety and hygiene issues, suggestions to help you to maintain a healthy, balanced diet, information on psychological effects and some other issues to consider. How are taste and smell affected by brain injury? The two senses can both be affected in a number of different ways and some definitions of the terms for the different conditions are provided below: Disorders of smell Anosmia Total loss of sense of smell Hyposmia Partial loss of sense of smell Hyperosmia Enhanced sensitivity to odours Phantosmia/Parosmia ‘False’ smells – Perceiving smells that aren’t there Dysosmia Distortion in odour perception Disorders of taste Dysgeusia Distortion or decrease in the sense of taste Ageusia Total loss of sense of taste Dysgensia Persistent abnormal taste Parageusia Perceiving a bad taste in the mouth 1 The two senses are connected and much of the sensation of taste is due to smell, so if the sense of smell is lost then the ability to detect flavour will be greatly affected. -

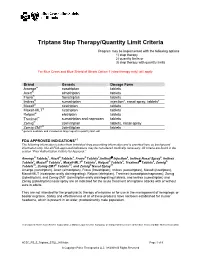

Triptans Step Therapy/Quantity Limit Criteria

Triptans Step Therapy/Quantity Limit Criteria Program may be implemented with the following options 1) step therapy 2) quantity limits or 3) step therapy with quantity limits For Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Illinois Option 1 (step therapy only) will apply. Brand Generic Dosage Form Amerge® naratriptan tablets Axert® almotriptan tablets Frova® frovatriptan tablets Imitrex® sumatriptan injection*, nasal spray, tablets* Maxalt® rizatriptan tablets Maxalt-MLT® rizatriptan tablets Relpax® eletriptan tablets Treximet™ sumatriptan and naproxen tablets Zomig® zolmitriptan tablets, nasal spray Zomig-ZMT® zolmitriptan tablets * generic available and included as target agent in quantity limit edit FDA APPROVED INDICATIONS1-7 The following information is taken from individual drug prescribing information and is provided here as background information only. Not all FDA-approved indications may be considered medically necessary. All criteria are found in the section “Prior Authorization Criteria for Approval.” Amerge® Tablets1, Axert® Tablets2, Frova® Tablets3,Imitrex® injection4, Imitrex Nasal Spray5, Imitrex Tablets6, Maxalt® Tablets7, Maxalt-MLT® Tablets7, Relpax® Tablets8, Treximet™ Tablets9, Zomig® Tablets10, Zomig-ZMT® Tablets10, and Zomig® Nasal Spray11 Amerge (naratriptan), Axert (almotriptan), Frova (frovatriptan), Imitrex (sumatriptan), Maxalt (rizatriptan), Maxalt-MLT (rizatriptan orally disintegrating), Relpax (eletriptan), Treximet (sumatriptan/naproxen), Zomig (zolmitriptan), and Zomig-ZMT (zolmitriptan orally disintegrating) tablets, and Imitrex (sumatriptan) and Zomig (zolmitriptan) nasal spray are all indicated for the acute treatment of migraine attacks with or without aura in adults. They are not intended for the prophylactic therapy of migraine or for use in the management of hemiplegic or basilar migraine. Safety and effectiveness of all of these products have not been established for cluster headache, which is present in an older, predominantly male population. -

European Patent Office of Opposition to That Patent, in Accordance with the Implementing Regulations

(19) TZZ _T (11) EP 2 666 772 B1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT SPECIFICATION (45) Date of publication and mention (51) Int Cl.: of the grant of the patent: C07D 409/04 (2006.01) C07D 209/16 (2006.01) 01.03.2017 Bulletin 2017/09 C07D 209/18 (2006.01) C07D 209/38 (2006.01) (21) Application number: 13173141.6 (22) Date of filing: 12.12.2003 (54) Synthesis of amines and intermediates for the synthesis thereof Synthese von Aminen und Zwischenverbindungen für die Synthese davon Synthèse d’amines et intermédiaires pour leur synthèse (84) Designated Contracting States: • DEMERSON C A ET AL: "ETODOLIC ACID AND AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB GR RELATED COMPOUNDS CHEMISTRY AND HU IE IT LI LU MC NL PT RO SE SI SK TR ANTIINFLAMMATORY ACTIONS OF SOME POTENT DI-AND TRISUBSTITUTED (30) Priority: 20.12.2002 EP 02406128 1,3,4,9-TETRAHYDROPYRANO not 3,4-B 3/4 INDOLE-I-ACETIC ACIDS", JOURNAL OF (43) Date of publication of application: MEDICINALCHEMISTRY, AMERICAN CHEMICAL 27.11.2013 Bulletin 2013/48 SOCIETY, vol. 19, no. 3, 1 March 1976 (1976-03-01), pages391-395, XP000940626, ISSN: (62) Document number(s) of the earlier application(s) in 0022-2623, DOI: 10.1021/JM00225A010 accordance with Art. 76 EPC: • HARUYASU ET ALL: "Possible metabolic 03799560.2 / 1 572 647 Intermediatesfrom IAA to beta-acid in Rice Bran", AGR. BIOL. CHEM., vol. 40, no. 12, 1976, pages (73) Proprietor: BASF SE 2465-2470, XP002714693, 67056 Ludwigshafen am Rhein (DE) • SOLL R M ET AL: "Multigram preparation of 1,8-diethyl-7-hydroxy-1,3,4,9-tetrahydropy (72) Inventors: rano[3,4-b]indole-1-acetic acid, a phenolic • Berens, Ulrich metabolite of the analgesic and antiinflammatory 79589 Binzen (DE) agent etodolac", THE JOURNAL OF ORGANIC • Dosenbach, Oliver CHEMISTRY, AMERICAN CHEMICAL SOCIETY 79415 Bad Bellingen (DE) [NOT]ETC. -

Patient Information Leaflet

Package Leaflet: Information for the user Sumatriptan 50 mg film-coated tablets Sumatriptan 100 mg film-coated tablets sumatriptan Read all of this leaflet carefully before you start using this medicine because it contains important information for you. • Keep this leaflet. You may need to read it again. • If you have any further questions, ask your doctor or pharmacist. • This medicine has been prescribed for you only. Do not pass it on to others. It may harm them, even if their signs of illness are the same as yours. • If you get any side effects, talk to your doctor or pharmacist. This includes any possible side effects not listed in this leaflet. See section 4. What is in this leaflet 1. What Sumatriptan tablet is and what it is used for 2. What you need to know before you use Sumatriptan tablet 3. How to use Sumatriptan tablet 4. Possible side effects 5. How to store Sumatriptan tablet 6. Contents of the pack and other information 1. What Sumatriptan tablet is and what it is used for Sumatriptan belongs to a group of medicines called serotonin receptor (5-HT1) agonists. Migraine headaches are thought to result from the dilatation of blood vessels. Sumatriptan constricts these blood vessels, thus relieving the migraine headache. Sumatriptan tablet is used to treat migraine attacks with or without aura (aura is a premonition usually connected with flashes of light, serrated images, stars or waves). 2. What you need to know before you use Sumatriptan tablet Do not use Sumatriptan tablet: - if you are allergic to sumatriptan or any of the other ingredients of this medicine (listed in section 6). -

Medication Guide 2012

DeKalb County D.U.I. Court Supervised Treatment Program MEDICATION GUIDE Medication Guide 2012 DeKalb County State Court Decatur, Georgia xxi ********** WELCOME TO THE DEKALB COUNTY D.U.I. COURT SUPERVISED TREATMENT PROGRAM. This 2012 Medication Guide was developed as a collaborative effort by Becky Pirouz, Pharm.D., Director of Pharmacy, Peachford Hospital, and by Lois Michalove, Treatment Coordinator for the DeKalb County D.U.I. Court Supervised Treatment Program, both of whom have extensive experience in addiction recovery and treatment. ********** The following information is intended to assist you in making decisions about medications. This may include those medications that you are prescribed and/or your selection of over-the-counter (OTC) products. Unintended exposure may compromise your treatment program. This is not an exhaustive list, but contains some of the medications that are most commonly used. If in doubt, always consult the Treatment Coordinator. Please inform your physician, dentist, pharmacist and other health care professionals that you are in a recovery program. WE ARE A ZERO-TOLERANCE PROGRAM! DO NOT COMPROMISE YOUR RECOVERY BY MAKING HIGH-RISK CHOICES! xxii - Section 1 – Drugs To Avoid The following drugs must not be used at any time. They are well known to be abused and even small amounts may result in relapse and are contraindicated in your treatment program. However, extenuating circumstances may occur which necessitates the short- term limited use of some of the drugs on this list in consultation with your physician, the Judge and the Treatment Coordinator. This decision should be made prior to your ingestion of any of the Drugs to Avoid. -

Let's Talk About . . . Migraine and Dizziness

LET’S TALK ABOUT . MIGRAINE AND DIZZINESS Migraine is almost as common as high blood Key points pressure in the Canadian population. It is more • A migraine is a severe headache. common than asthma or diabetes. An estimated 300,000 Canadians suffer needlessly because they • Of over 300 types of migraine, dizziness is have either been misdiagnosed or not diagnosed a symptom of two: migraine with brainstem with chronic migraine. aura and vestibular migraine. • See a doctor who specialized in headaches for accurate diagnosis. What are the symptoms of migraine with dizziness? • Lifestyle changes may help prevent or lessen the occurrence of migraine. Common symptoms include: • Medication may help prevent migraine. • Visual aura – you may see flashes of light or have blind spots in your vision. • Localized pain behind or near the eye on one Note: Concussion also causes migraine-type side of your head. dizziness – concussion sufferers can substitute the • Light, sound (hyperacusis) and odor sensitivity word “concussion” for “migraine” in the information (hyperosmia). You may have some sensitivity below. daily and increased sensitivity when you have migraine. • Visual vestibular mismatch (the brain’s What is migraine? hypersensitivity to motion) is common in Migraine is a neurovascular headache, meaning it migraine-type brains both episodically and can be triggered by annoyance or disturbance to chronically. Sometimes it will occur without the nerves or blood vessels in the brain. All headache and you may feel “off” for an hour or migraines are caused by the same type of two. neurotransmitter dysregulation and respond to the • Vertigo (spinning sensation) – it may start same treatments. -

Guideline for Preoperative Medication Management

Guideline: Preoperative Medication Management Guideline for Preoperative Medication Management Purpose of Guideline: To provide guidance to physicians, advanced practice providers (APPs), pharmacists, and nurses regarding medication management in the preoperative setting. Background: Appropriate perioperative medication management is essential to ensure positive surgical outcomes and prevent medication misadventures.1 Results from a prospective analysis of 1,025 patients admitted to a general surgical unit concluded that patients on at least one medication for a chronic disease are 2.7 times more likely to experience surgical complications compared with those not taking any medications. As the aging population requires more medication use and the availability of various nonprescription medications continues to increase, so does the risk of polypharmacy and the need for perioperative medication guidance.2 There are no well-designed trials to support evidence-based recommendations for perioperative medication management; however, general principles and best practice approaches are available. General considerations for perioperative medication management include a thorough medication history, understanding of the medication pharmacokinetics and potential for withdrawal symptoms, understanding the risks associated with the surgical procedure and the risks of medication discontinuation based on the intended indication. Clinical judgement must be exercised, especially if medication pharmacokinetics are not predictable or there are significant risks associated with inappropriate medication withdrawal (eg, tolerance) or continuation (eg, postsurgical infection).2 Clinical Assessment: Prior to instructing the patient on preoperative medication management, completion of a thorough medication history is recommended – including all information on prescription medications, over-the-counter medications, “as needed” medications, vitamins, supplements, and herbal medications. Allergies should also be verified and documented. -

Olfactory Dysfunction

Olfactory Dysfunction: By Steven Sobol, MD, MSc; Saul Frenkiel, MD, FRCSC; and Debbie Mouadeb he sense of smell plays an important role in protecting Tman from environmental dangers, such as fire, natural gas leaks and spoiled food. Physiologically, the chemical senses aid in normal digestion by triggering gastrointestinal secretions.1 Smell influences the palatability of food. Defects in the sense of smell are associated with alterations in perceptions of flavor, leading to anorexia and weight loss. Psychologically, smell is powerful in establishing strong positive and negative memories, and affects socialization and interpersonal relationships. Smell dysfunctions often mean considerable disability and a lower quality of life. Loss or decreased olfactory function affects approximately one per cent of Americans under the age of 60 and more than half the population over that age.2 Aside from having a substantial impact on an individual’s quality of life, olfactory dysfunction may signal an underlying disease. Smell disorders have been largely overlooked by the medical community because of a lack of knowledge and understanding of the sense of smell and its disease states, as well its diagnosis and management. Patients with olfactory disorders need to be clinically assessed, and the etiology and anatomical location of their disorder should be sought out. The Canadian Journal of Diagnosis / August 2002 55 Olfactory Dysfunction Summary What are the causes of olfactory dysfunction? 1.Conductive olfactory loss is any process that causes sufficient obstruction in the nose preventing odorant molecules from reaching the olfactory epithelium. 2.Sensorineural olfactory loss is any process that directly affects and impairs either the olfactory epithelium or the central olfactory pathways.