Natural Dyeing of Textiles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Improving the Fastness Properties of Cotton Fabric Through the Implementation of Different Mordanting Agents Dyed with Natural Dye Extracted from Marigold

American Journal of Polymer Science and Engineering Islam M, American Journal of Polymer Sciencehttp://www.ivyunion.org/index.php/ajpse/ and Engineering 2016, 4:8-16 Page 1 of 17 Research Article Improving the Fastness Properties of Cotton Fabric through the Implementation of Different Mordanting Agents Dyed with Natural Dye Extracted from Marigold Mazharul Islam1, K. M. Faridul Hasan1*, Hridam Deb1, Md Faisal Ashik2, Weilin Xu1 1 School of Textile Science and Engineering, Wuhan Textile University, Wuhan, China 2 School Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Wuhan Textile University, Wuhan, China Abstract Extraction of natural dyes for the coloration of Textile substrate is one the most important research area to the researchers. It is tried to extract the natural dyes from marigold flower through using the different kinds of mordanting agents. In this research, a particular source is used for dyes extraction. Before the extraction Patel of the marigold flower was extracted and dried on sunlight, subsequently dried in room temperature due to preserve the natural colorant. The natural dyes were extracted by boiling the above substrates in water without any chemicals. As mordant, Potash Alum [K2Al2(SO4)3.24H2O], Ferrous Sulphate(FeSO4),Copper Sulphate (CuSO4),Nickel (II) Sulphate (NiSO4),Potassium Dichromate (K2Cr2O7),Stannous Chloride(SnCl2) were used. The mordanting procedures were followed same for all the experiments. The treatment runtime was 60 minute at 100oC. After mordanting each sample fabric was kept for 24 hours for conditioning and then the dyeing was done. But as there is no particular dyeing method for natural dyeing so it is followed some trial and some convenient methods were made after trial for several times. -

Indigo and the Tightening Thread 1 for the Journal of Weavers, Spinners and Dyers 231 Autumn 2009

Indigo and the Tightening Thread 1 For the Journal of Weavers, Spinners and Dyers 231 Autumn 2009 Jane Callender Natural indigo and synthetic Many varieties of indigo bearing plants flourish in indigo are both available to us. hot and temperate climates all over the world A key date in textile history is and more than one can be found in any one 1856 when 18 year old assistant region. The European indigo bearing plant is chemist William Perkins, Isastis Tinctoria, known as woad. stumbled upon, developed and Although there are an incredible number of patented the first synthetic species and subspecies, ‘indican’, the actual dyestuff from coal tar. ‘Perkins chemical source and precursor of indigo, a tiny Purple’ became known as organic molecule, is common to all. (A Large Mauvine. Later the German percentage in the woad precursor is also indican, chemist Adolf von Baeyer with Isatan B making up the rest) Consequently synthesized indigo which was ‘…..the resulting blue is indistinguishable even to sold on the open market in the specialist’ (Balfour-Paul) 1897. Astonishingly, the Harvesting the plants, extracting the indican molecular structure of natural present within the leaves and storage of the and synthetic indigo, as it was indigo pigment differs from country to country. then and as it is now, is the Though glycosides and enzymes vary, as does the same. alkalinity level and temperature of the water in which leaves are immersed, the following Dyeing can only be done graphics illustrates, in essence, the acquisition of with indigo in its soluble form natural indigo through fermentation. -

Folk Traditions of Carved Board Clamp Resist Dyeing in Zhejiang Province

8ISS Symposium-Panel on Clamp, Pole-Wrap, Tied-Resist Dyeing CHINESE BLUE & WHITE ITAJIME (JIAXIE): Folk Traditions of Carved Board Clamp Resist Dyeing in Zhejiang Province Tomoko TORIMARU Association of Fukuoka District Vocational Training, Fukuoka, Japan (Independent Scholar - History and Technology in Textiles: Japanese, Chinese, and other Traditional Asian Textiles) 1-5-10-501, Futsukaichiminami, Chikushino, Fukuoka, Japan, 818-0057 Email: [email protected] Abstract some efforts by local government to preserve this This is a report on our field studies taken to identify and vanishing practice, it simply cannot sustain itself without observe in China the process of itajime shibori, or carved sufficient demand. board clamp resist dyeing known as Jiaxie in Chinese and pronounced 'Kyokechi' in Japanese. There is very little In 2002 and 2003, we traveled to Yishan, Cangnan, known history of this craft as generally not much attention Zhejiang Province, and visited what is now officially is paid in China to their folk traditions. designated ―Zhongnuo Minjian Gongyi Jiaxie Zuofang,‖ or roughly 'Chinese People's Art Craft Jiaxie Studio'. The 1. Introduction name suggests an effort by local government to preserve Chinese jiaxie, pronounced ―kyokechi‖ in Japanese and the area's folk craft traditions. There, we observed jiaxie known as itajime shibori, is a type of carved board clamp master, Mr. Xunlang Xue. As a sign of the times, Mr. Xue resist dyeing. Different from wax or paste resist, jiaxie performs his craft only on request as there is hardly any employs resists made of carved wooden boards. In this need nor much demand for him to sustain a regular technique, cloth is sandwiched tightly between two boards practice. -

Adire Cloth: Yoruba Art Textile

IROHIN Taking Africa to the Classroom SPRING 2001 A Publication of The Center for African Studies University of Florida IROHIN Taking Africa to the Classroom SPRING 2001 A Publication of The Center for African Studies University of Florida Editor/Outreach Director: Agnes Ngoma Leslie Layout & Design: Pei Li Li Assisted by Kylene Petrin 427 Grinter Hall P.O. Box 115560 Gainesville, FL. 32611 (352) 392-2183, Fax: (352) 392-2435 Web: http://nersp.nerdc.ufl.edu/~outreach/ Center for African Studies Outreach Program at the University of Florida The Center is partly funded under the federal Title VI of the higher education act as a National Resource Center on Africa. As one of the major Resource Centers, Florida’s is the only center located in the Southeastern United States. The Center directs, develops and coordinates interdisci- plinary instruction, research and outreach on Africa. The Outreach Program includes a variety of activities whose objective is to improve the teaching of Africa in schools from K-12, colleges, universities and the community. Below are some of the regular activities, which fall under the Outreach Program. Teachers’ Workshops. The Center offers in- service workshops for K-12 teachers on the teaching of Africa. Summer Institutes. Each summer, the Center holds teaching institutes for K-12 teachers. Part of the Center’s mission is to promote Publications. The Center publishes teaching African culture. In this regard, it invites resources including Irohin, which is distributed to artists such as Dolly Rathebe, from South teachers. In addition, the Center has also pub- Africa to perform and speak in schools and lished a monograph entitled Lesson Plans on communities. -

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI Filozofická Fakulta

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI Filozofická fakulta Katedra asijských studií Estetické vnímání krásy ženy v Japonsku Aesthetic perception of woman´s beauty in Japan Bakalářská diplomová práce Autor práce: Pomklová Lucie Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Sylva Martinásková - ASJ Olomouc 2013 Kopie zadání diplomové práce Prohlašuji, že jsem diplomovou práci vypracovala samostatně a uvedla veškeré použité prameny a literaturu V Olomouci dne _______________________ Poděkování: Na tomto místě bych chtěla velice poděkovat Mgr. Sylvě Martináskové za konzultace, ochotu, flexibilitu při řešení jakýchkoliv problémů a odborné vedení mé práce. Díky jejím cenným radám a podnětům mohla tato práce vzniknout. Ediční poznámka Ve své práci používám anglický přepis japonských názvů společně se znaky nebo slabičnou abecedou, které budu užívat u ér, období, uvedených japonských termínů a jmen osob. Japonská jména uvádím v japonském pořadí čili první příjmení a za ním teprve následuje jméno osobní, ženská jména jsou uvedena v nepřechýlené podobě. Pro obecně známá místní jména či termíny, u kterých je český přepis již pevně stanoven pravidly českého pravopisu, používám tento do češtiny přejatý tvar. Kurzívu budu používat pro méně známé termíny, názvy ér a období a také pro citace. Používám citační normu ISO 690. Obsah 1 Úvod ................................................................................................................................... 8 2 Protohistorické období .................................................................................................. -

Batik of Java: Global Inspiration Maria Wronska-Friend the Cairns Institute, James Cook University, [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2018 Batik of Java: Global Inspiration Maria Wronska-Friend The Cairns Institute, James Cook University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Art Practice Commons, Fashion Design Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Fine Arts Commons, and the Museum Studies Commons Wronska-Friend, Maria, "Batik of Java: Global Inspiration" (2018). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 1080. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/1080 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings 2018 Presented at Vancouver, BC, Canada; September 19 – 23, 2018 https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/ Copyright © by the author(s). Batik of Java: Global Inspiration Maria Wronska-Friend [email protected] Batik, the resist-dyeing technique of patterning cloth through the application of wax, has been known since antiquity in several parts of the world, but it reached its highest level of complexity on the island of Java. While deeply embedded in local traditions and associated with the beliefs, philosophy, and social order of Java, during the last two centuries batik has become a powerful cultural intermediary connecting Indonesia with other parts of the world. -

Resist Dyeing - Wikipedia Page 1 of 3

Resist dyeing - Wikipedia Page 1 of 3 Resist dyeing From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Resist dyeing (resist-dyeing) is a term for a number of traditional methods of dyeing textiles with patterns. Methods are used to "resist" or prevent the dye from reaching all the cloth, thereby creating a pattern and ground. The most common forms use wax, some type of paste made from starch or mud,[1] or a mechanical resist that manipulates the cloth such as tying or stitching. Another form of resist involves using a chemical agent in a specific type of dye that will repel another type of dye printed over the top. The best-known varieties today include tie-dye and batik. Contents ◾ 1 Basic methods ◾ 2History ◾ 3 Traditions using wax or paste Indonesian batik fabric ◾ 4 Traditions using tying or stitching ◾ 5 Traditions using printing ◾ 6 Other traditions ◾ 7See also ◾ 8 References Basic methods Wax or paste: melted wax or some form of paste is applied to cloth before being dipped in dye. Wherever the wax has seeped through the fabric, the dye will not penetrate. Sometimes several colors are used, with a series of dyeing, drying and waxing steps. The wax may also be applied to another piece of cloth to make a stencil, which is then placed over the cloth, and dye applied to the assembly; this is known as resist printing. Paper stencils may also be used; another type of resist printing. The same method is used in art in printmaking, in one form of screenprinting. Mechanical: the cloth is tied,stitched, or clamped using clothespegs or wooden blocks to shield areas of the fabric. -

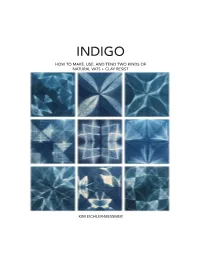

Indigo How to Make, Use, and Tend Two Kinds of Natural Vats + Clay Resist

INDIGO HOW TO MAKE, USE, AND TEND TWO KINDS OF NATURAL VATS + CLAY RESIST KIM EICHLER-MESSMER Background Indigo cultivation is thought to have existed in the Indus Valley (present-day Pakistan and Northwest India) more than 5,000 years ago and there have been recent discoveries in Peru that date Indigo cultivation and use to 6,000 years ago. It is the only plant pigment that creates a permanent blue dye, and varieties of the plant were discovered and used as dye in many different parts of the world including Africa, Asia, South and Central America, and Europe. The word “indigo” is now used to describe the dyestuff, the plant, and the color. There are a variety of plants that contain the dye molecule indigotin. Indigofera tinctoria, indigofera suffruticosa, Persicaria tinctoria, and Isatis tinctoria (woad) are the most common plants to be grown for their indigo content. Each plant thrives in a different climate. Indigotin is the only blue natural dye, and it is extracted from the leaves of the plant in a number of ways, including water extraction and composting. Indigo is a very unusual type of dye called a vat dye. Most natural dyes are mordant dyes. They can easily be extracted in water or dissolved in water and they require a mineral mordant (usually alum) to bond with the fiber. Indigo does not require a mordant to bond and the indigo dye molecule is not water-soluble. If you add indigo powder to water the indigo will not dissolve. It will float around, suspended in the water. -

Resist-Dyeing As a Possible Ancient Transoceanic Transfer

Resist-Dyeing as a Possible Ancient Transoceanic Transfer Stephen C. Jett Introduction The controversial question of whether signicant cultural contact occurred between the peoples of the Eastern and Western Hemispheres before the time of Columbus is one of paramount cultural-historical and theoretical importance. Its potential resolution rests on many kinds of evidence.1 Among these are cultural similarities of various sorts. A principal aim of research on this issue is determining which shared traits may have been the result of cultural exchange. From an evidentiary standpoint, the most convincing cultural commonalities involve either highly arbitrary traits (such as most lexemes) or highly complex phenomena whose independent development in distant geographical areas seems very improbable. Of the latter type is the technology of cloth manufacture, which includes ber extraction, carding, spinning, and weaving, often in elaborate ways. When advanced coloring methods are added to all the other sophisticated aspects of textile production, the result is an exceedingly complicated system of phenomena. As one scholar noted, “Textiles are one of the strangest inventions ever produced by man.”2 Unfortunately, very little research has been undertaken comparing Old and New World textile arts in the context of the transoceanic-diffusion question. In 1985 science historians Joseph Needham and Lu Gwei-Djen observed, “We have not found any comparative summary of textile technology in the Old and New Worlds, and without this it would be fruitless to offer any observations.”3 In view of this gap, I have attempted to address in a preliminary way the topic of textile manufacture as evidence for cultural diffusion between the hemispheres. -

Asian Knowledge and the Development of Calico Printing In

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap This paper is made available online in accordance with publisher policies. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item and our policy information available from the repository home page for further information. To see the final version of this paper please visit the publisher’s website. Access to the published version may require a subscription. Author(s): Giorgio Riello Article Title: Asian knowledge and the development of calico printing in Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries Year of publication: 2010 Link to published version: http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1017/S1740022809990313 Publisher statement: Riello, G. (2010). Asian knowledge and the development of calico printing in Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Journal of Global History , Vol. 5, pp.1-28 Journal of Global History (2010) 5, pp. 1–28 ª London School of Economics and Political Science 2010 doi:10.1017/S1740022809990313 Asian knowledge and the development of calico printing in Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries* Giorgio Riello Department of History, University of Warwick, Coventry CV4 7AL, UK E-mail: [email protected] Abstract From the seventeenth century, the brilliance and permanence of colour and the exotic nature of imported Asian textiles attracted European consumers. The limited knowledge of colouring agents and the general absence of textile printing and dyeing in Europe were, however, major impediments to the development of a cotton textile-printing and -dyeing industry in Europe. This article aims to chart the rise of a European calico-printing industry in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries by analysing the knowledge transfer of textile-printing techniques from Asia to Europe. -

0-23 Evolution of Adire Texti1e Design of Nigeria: Diffusion & Impact on Globalization

0-23 Evolution of Adire Texti1e Design of Nigeria: Diffusion & Impact on Globalization. PRISCILLA NNENNA EZEMA Fed. College Of Education,Eha-Amufu. Nigeria I • INTRODUTION This paper design to address the origin and antecedent of Adire Textile design of Nigeria and how the practice has acquired inter cultural and global significance in the present Times. This becomes necessary because the world is under giving fast change and the world of fashion is no exception to this dynamism. There are intercultural exchange tendencies which justify the craze for novelty and conformity which are the major justifications for moving along with fashion trend. Fabrics, styles and design have undergone innovations and evolutionary trends in various ways resulting to the present advanced status. Adire textile design is by no means an exception to this rule . H. What is Adire? Adire is an al 1 time textile design, which originated from the Western part of Nigeria The Yoruba ethnic group in general and Abeokuta in particular. Enem (1999) contended That the Yoruba people are the second largest group of people in Nigeria after the Hausa. They are followed by the Igbo. They are believed to be the descendants of a legendary figure, Od나d냐wa who first settle at He- Ife. Yoruba dresses include long Agbada, Buba, Iro, Fil가, Gele mostly made of 멇so oke? Ankara and Adire. Adire textile comes in different design and colures which make it convenient and relevant for use for different purposes and for various occasions. For instance, Adire is used for sewing garments of different, Caftan, etc. and for household article 1 ike cushion covers, throw-puffs and blinds for -81 doors and windows. -

Arimatsu to Africa: Shibori Textiles Developed for African Trade in 1948–49 Yoshiko Iwamoto Wada [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2016 Arimatsu to Africa: Shibori Textiles Developed for African Trade in 1948–49 Yoshiko Iwamoto Wada [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Art Practice Commons, Fashion Design Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Fine Arts Commons, and the Museum Studies Commons Wada, Yoshiko Iwamoto, "Arimatsu to Africa: Shibori Textiles Developed for African Trade in 1948–49" (2016). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 1017. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/1017 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Crosscurrents: Land, Labor, and the Port. Textile Society of America’s 15th Biennial Symposium. Savannah, GA, October 19-23, 2016. 549 Arimatsu to Africa: Shibori Textiles Developed for African Trade in 1948–49 Yoshiko Iwamoto Wada [email protected] Shibori is a traditional Japanese textile term now widely used to classify a variety of patterns created on cloth by plucking, stitching, folding and then tightly knotting, binding, or clamping to compress and selectively resist dye penetration.