Bronze Age.PDF

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INLAND NAVIGATION AUTHORITIES the Following Authorities Are Responsible for Major Inland Waterways Not Under British Waterways Jurisdiction

INLAND NAVIGATION AUTHORITIES The following authorities are responsible for major inland waterways not under British Waterways jurisdiction: RIVER ANCHOLME BRIDGEWATER CANAL CHELMER & BLACKWATER NAVIGATION The Environment Agency Manchester Ship Canal Co. Essex Waterways Ltd Anglian Region, Kingfisher House Peel Dome, Trafford Centre, Island House Goldhay Way, Orton Manchester M17 8PL Moor Road Peterborough PE2 5ZR T 0161 629 8266 Chesham T 08708 506 506 www.shipcanal.co.uk HP5 1WA www.environment-agency.gov.uk T: 01494 783453 BROADS (NORFOLK & SUFFOLK) www.waterways.org.uk/EssexWaterwaysLtd RIVER ARUN Broads Authority (Littlehampton to Arundel) 18 Colgate, Norwich RIVER COLNE Littlehampton Harbour Board Norfolk NR3 1BQ Colchester Borough Council Pier Road, Littlehampton, BN17 5LR T: 01603 610734 Museum Resource Centre T 01903 721215 www.broads-authority.gov.uk 14 Ryegate Road www.littlehampton.org.uk Colchester, CO1 1YG BUDE CANAL T 01206 282471 RIVER AVON (BRISTOL) (Bude to Marhamchurch) www.colchester.gov.uk (Bristol to Hanham Lock) North Cornwall District Council Bristol Port Company North Cornwall District Council, RIVER DEE St Andrew’s House, St Andrew’s Road, Higher Trenant Road, Avonmouth, Bristol BS11 9DQ (Farndon Bridge to Chester Weir) Wadebridge, T 0117 982 0000 Chester County Council PL27 6TW, www.bristolport.co.uk The Forum Tel: 01208 893333 Chester CH1 2HS http://www.ncdc.gov.uk/ RIVER AVON (WARWICKSHIRE) T 01244 324234 (tub boat canals from Marhamchurch) Avon Navigation Trust (Chester Weir to Point of Air) Bude Canal Trust -

Some Elements of the Landscape History of the Five 'Low Villages'

Some elements of the Landscape History of the five ‘Low Villages’, North Lincolnshire. Richard Clarke. Some elements of the landscape history of the five ‘Low Villages’, north Lincolnshire. The following twelve short articles were written for the Low Villages monthly magazine in 2014 and 2015. Part One was the first, and so on. In presenting all 12 as one file certain formatting problems were encountered, particularly with Parts two and three. Part One. Middlegate follows the configuration of the upper scarp slope of the chalk escarpment from the top of the ascent in S. Ferriby to Elsham Hill, from where a direct south-east route, independent of contours, crosses the ‘Barnetby Gap’ to Melton Ross. The angled ascent in S. Ferriby to the western end of the modern chalk Quarry is at a gradient of 1:33 and from thereon Middlegate winds south through the parishes of Horkstow, Saxby, Bonby and Worlaby following the undulations in the landscape at about ten meters below the highest point of the scarp slope. Therefore the route affords panoramic views west and north-west but not across the landscape of the dip slope to the east. Cameron 1 considered the prefix middle to derive from the Old English ‘middel’ and gate from the Old Norse ‘gata’ meaning a way, path or road. From the 6th and 7th centuries Old English (Anglo-Saxon) terms would have mixed with the Romano-British language, Old Norse (Viking) from the 9 th century. However Middlegate had existed as a route-way long before these terms could have been applied, it being thought to have been a Celtic highway, possibly even Neolithic and thus dating back five millennia. -

Climate Change, Recreation and Navigation

Climate change, recreation and navigation Science report: SC030303 SCHO0707BMZG-E-P The Environment Agency is the leading public body protecting and improving the environment in England and Wales. It’s our job to make sure that air, land and water are looked after by everyone in today’s society, so that tomorrow’s generations inherit a cleaner, healthier world. Our work includes tackling flooding and pollution incidents, reducing industry’s impacts on the environment, cleaning up rivers, coastal waters and contaminated land, and improving wildlife habitats. This report is the result of research commissioned and funded by the Environment Agency’s Science Programme. Published by: Author(s): Environment Agency, Rio House, Waterside Drive, Aztec West, R. Lamb, J. Mawdsley, L. Tattersall, M. Zaidman Almondsbury, Bristol, BS32 4UD Tel: 01454 624400 Fax: 01454 624409 Dissemination Status: www.environment-agency.gov.uk Publicly available / released to all regions ISBN: 978-1-84432-797-3 Keywords: Strong stream advice, climate change, low flows, navigation, © Environment Agency July 2007 High flows, recreation. All rights reserved. This document may be reproduced with prior Research Contractor: permission of the Environment Agency. JBA Consulting, South Barn, Broughton Hall, Skipton, BD23 3AE +44 (0)1756 799 919 The views expressed in this document are not necessarily those of the Environment Agency. Environment Agency’s Project Manager: Naomi Savory, Richard Fairclough House, Knutsford Road, This report is printed on Cyclus Print, a 100% recycled stock, Warrington. which is 100% post consumer waste and is totally chlorine free. Water used is treated and in most cases returned to source in Science Project Number: better condition than removed. -

Lincolnshire Local Flood Defence Committee Annual Report 1996/97

1aA' AiO Cf E n v ir o n m e n t ' » . « / Ag e n c y Lincolnshire Local Flood Defence Committee Annual Report 1996/97 LINCOLNSHIRE LOCAL FLOOD DEFENCE COMMITTEE ANNUAL REPORT 1996/97 THE FOLLOWING REPORT HAS BEEN PREPARED UNDER SECTION 12 OF THE WATER RESOURCES ACT 1991 Ron Linfield Front Cover Illustration Area Manager (Northern) Aerial View of Mablethorpe North End Showing the 1996/97 Kidding Scheme May 1997 ENVIRONMENT AGENCY 136076 LINCOLNSHIRE LOCAL FLOOD DEFENCE COMMITTEE ANNUAL REPORT 1996/97 CONTENTS Item No Page 1. Lincolnshire Local Flood Defence Committee Members 1 2. Officers Serving the Committee 3 3. Map of Catchment Area and Flood Defence Data 4 - 5 4. Staff Structure - Northern Area 6 5. Area Manager’s Introduction 7 6. Operations Report a) Capital Works 10 b) Maintenance Works 20 c) Rainfall, River Flows and Flooding and Flood Warning 22 7. Conservation and Flood Defence 30 8. Flood Defence and Operations Revenue Account 31 LINCOLNSHIRE LOCAL FLOOD DEFENCE COMMITTEE R J EPTON Esq - Chairman Northolme Hall, Wainfleet, Skegness, Lincolnshire Appointed bv the Regional Flood Defence Committee R H TUNNARD Esq - Vice Chairman Witham Cottage, Boston West, Boston, Lincolnshire D C HOYES Esq The Old Vicarage, Stixwould, Lincoln R N HERRING Esq College Farm, Wrawby, Brigg, South Humberside P W PRIDGEON Esq Willow Farm, Bradshaws Lane, Hogsthorpe, Skegness Lincolnshire M CRICK Esq Lincolnshire Trust for Nature Conservation Banovallum House, Manor House Street, Homcastle Lincolnshire PROF. J S PETHICK - Director Cambs Coastal Research -

Anglian Navigation Byelaws

boating the right way Recreational Byelaws Anglian Waterways We are the Environment Agency. It’s our job to look after your environment and make it a better place – for you, and for future generations. Your environment is the air you breathe, the water you drink and the ground you walk on. Working with business, Government and society as a whole, we are making your environment cleaner and healthier. The Environment Agency. Out there, making your environment a better place. Published by: Environment Agency Kingfisher House Goldhay Way, Orton Goldhay Peterborough, Cambridgeshire PE2 5ZR Tel: 0870 8506506 Email: [email protected] www.environment-agency.gov.uk © Environment Agency All rights reserved. This document may be reproduced with prior permission of the Environment Agency. Recreational Waterways (General) Byelaws 1980 (as amended) The Anglian Water Authority under and ‘a registered pleasure boat’ by virtue of the powers and authority means a pleasure boat registered vested in them by Section 18 of the with the Authority under the Anglian Water Authority Act 1977 and provisions of the Anglian Water of all other powers them enabling Authority Recreational Byelaws hereby make the following Byelaws. - Recreational Waterways (Registration) 1979 1 Citation These byelaws may be cited as the (ii) Subject as is herein otherwise ‘Anglian Water Authority, Recreational expressly provided these byelaws Waterways (General) Byelaws 1980’. shall apply to the navigations and waterways set out in Schedule 1 2 Interpretation and Application of the Act. (i) In these byelaws, unless the context or subject otherwise 3 Damage, etc. requires, expressions to which No person shall interfere with or meanings are assigned by the deface Anglian Water Authority Act (i) any notice, placard or notice 1977 have the same respective board erected or exhibited by meanings, and the Authority on a recreational ‘the Act’ means the Anglian Water waterway or a bank thereof. -

UPDATED EMERGENCY NAVIGATION SEVERE RESTRICTION NOTICE Anglian Waterways All Rivers & Locations Listed DATE: 27 March

UPDATED EMERGENCY NAVIGATION SEVERE RESTRICTION NOTICE Section 15 Anglian Water Authority Act 1977 Anglian Waterways All Rivers & Locations Listed _________________________________________________________ DATE: 27 March 2020 – Until at least 14 April 2020. __________________________________________________ LOCATION: Anglian Waterways - All Navigations __________________________________________________ DETAILS: EMERGENCY NOTICE OF SEVERE NAVIGATION RESTRICTION OF ALL ASSISTED PASSAGE LOCKS Following the Prime Ministers announcement on 23 March 2020 about the UK’s heightened response to the Coronavirus emergency, we have taken the difficult decision to introduce limits to the use of our waterways to protect our staff, customers and stop all non-essential travel. From 4pm on Friday 27th March 2020 the following lock sites where we provide assisted passage will be severely restricted and closed until further notice for all non- essential travel. If you believe you need passage for essential reasons please contact the Waterways Duty Officer via our incident number any time on: 0800 80 70 60. South Ferriby Lock on the River Ancholme; Black Sluice Lock on the Black Sluice Navigation at Boston; Fulney Lock on the River Welland in Spalding; Dog-in-a-Doublet Lock on the River Nene; Denver Lock at Denver on the Ely Ouse / Tidal River Great Ouse and; Hermitage Lock, Earith on the River Great Ouse (Bedford Ouse). Please make sure you return to your home mooring, or to a point of safe mooring, before these lock site severe restrictions are imposed. We will keep these severe restrictions under constant review in the light of the developing situation and advice from Government, but we expect them to be in place until at least 14 April 2020. -

South Ferriby Heritage Trail

REVISED FINAL PDF 26/11/10 South Humber HERITAGE TRAIL SOUTH FERRIBY A Secret of St Nicholas Church On the Heritage Trail Wildfowling on Read’s Island Set above the porch is a 10th century carved stone depicting a bishop, perhaps The South Humber Heritage Trail is split in two sections and can be walked in Read’s Island is a peaceful wildlife haven with a resident herd St Nicholas, the patron saint of children either direction between Burton-upon-Stather and Winteringham and between of fallow deer and a flourishing population of the elegant avocet. and fishermen. The stone is probably a Barton-upon-Humber and South Ferriby. There are several car parks along the trail and regular bus services between the villages. The island was reclaimed from a sandbank in the 19th century relic from an earlier church as the present building is of 13th century date. Unusually, and was inhabited by tenant farmers until 1989. The tradition Along the trail are seven information panels at Burton-upon-Stather picnic area; the church is oriented north-south. of wildfowling has strong links with the area and was popular Countess Close medieval earthwork at Alkborough; the Humber bank at Whitton; in the 1950s when low-lying punts were used with specially Winteringham Haven; River Ancholme Car Park at South Ferriby; the Old Cement Works at Far Ings; and the Waters’ Edge at Barton-upon-Humber. adapted guns. The South Humber Area Joint Council of Traces of Iron Age Settlers Wildfowling Clubs now oversees the sport. A balanced approach Evidence of an Iron Age settlement Within this pack are leaflets providing information about the South Humber to shooting and conservation is maintained and today the lies on the edge of the Humber around Heritage Trail and each of the five villages along the trail, and details of local Humber Estuary is a thriving habitat for waders and wildfowl. -

DRAFT Feb March Edition 1 2018

HIBALDSTOW VILLAGE VOICE Volume 21 - Edition 4: August/September 2018 What does it cost? Full page is £24 (portrait) Half page is £12 (landscape) Quarter page is £6 (portrait) For more information contact: Sylvia Wattam 01652 652790 We need you to provide your adverts, send your adverts to: [email protected] Note: New adverts or changes to current adverts need submitting before the deadline for the next edition date shown inside the front cover. We’re Looking for Volunteers! If you’d like to help with the Village Voice, please get in touch we have a number of roles available! Email: [email protected] It’s been an amazing few weeks with the weather, hope everyone is enjoying it! Here’s the next edition of the Hibaldstow Village Voice for August and Septem- ber. Thankyou to those who have emailed me about helping with the village Diary Dates 2018 voice, we really appreciate it! If you know of anyone in the village that can help Event Day Venue Time as we’re still in need of more volunteers, it takes a lot of time to produce this magazine, and sharing this time with more people would really help! Short Mat Bowls Club Every Monday Village Hall 2.00pm For the next edition of the Village Voice, please submit your content for articles Scouts Every Monday Village Hall 5.45pm and adverts by: Tuesday 11 September 2018. 11.00am - Rural Day Centre Every Tuesday Village Hall 2.00pm Disclaimer Kurling Every Tuesday Village Hall 2.00pm The opinions, beliefs and viewpoints expressed by the various authors of articles and letters published with in "The Village Voice" publication do not necessarily Zumba Every Wednesday Village Hall 6.00pm reflect the opinions, beliefs and viewpoints of the Editor, Producers or Short Mat Bowls Club Every Wednesday Village Hall 7.15pm Committee. -

1 the UNIVERSITY of LINCOLN the Behaviour and Ecology of Adult

THE UNIVERSITY OF LINCOLN The behaviour and ecology of adult common bream Abramis brama (L.) in a heavily modified lowland river A Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Christopher John Gardner B.Sc. (Hons) September 2013 1 CONTENTS Publications and outputs 5 List of tables 6 List of figures 7 Acknowledgements 12 Abstract 13 1. Rivers, fish and human interventions 15 1.1 General introduction 15 1.2 Objectives 17 1.3 A ‘natural’ lowland riverine ecosystem 17 1.4 Anthropogenic impacts on lowland riverine ecosystems 18 1.5 Fish ecology and rivers 21 1.6 Common bream ecology 23 1.7 Studying spatio-temporal behaviour of fishes with telemetry techniques 29 1.8 Proposed study 33 2. The ecology of the lower River Witham 35 2.1 Objectives 35 2.2 The lower River Witham 35 2.2.1 Background 35 2.2.2 History 36 2.2.3 Catchment and land use 39 2.2.4 Water quality 39 2.2.5 Biological quality 40 2.2.6 Flow regime and flood events 41 2.2.7 Water level management 43 2.2.8 Trent-Witham-Ancholme water transfer scheme 43 2.2.9 Morphology 43 2.2.10 Habitat assessments 45 2.2.11 Barriers to fish migration 49 2.2.12 River uses 49 2.2.13 Conservation 49 2.2.14 Fishery assessments 50 2.2.15 Water Framework Directive classification 57 2.3 Discussion 57 2.3.1 Water quality 57 2.3.2 Biological quality 58 2.3.3 Habitat assessments 58 2.3.4 Fishery assessments 58 3. -

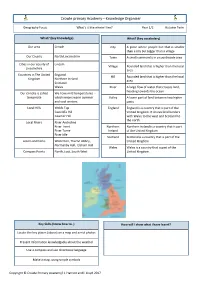

Crowle Primary Academy—Knowledge Organiser

Crowle primary Academy—Knowledge Organiser Geography Focus What’s it like where I live? Year 1/2 Autumn Term What? (key knowledge) What? (key vocabulary) Our area Crowle City A place where people live that is smaller than a city but bigger than a village Our County North Lincolnshire Town A small community in a countryside area Cities in our county of Lincoln Village Rounded land that is higher than the local Lincolnshire area Countries in The United England Hill Rounded land that is higher than the local Kingdom Northern Ireland area Scotland Wales River A large flow of water that crosses land, heading towards the ocean Our climate is called We have mild temperatures - temperate which means warm summer Valley A lower part of land between two higher and cool winters. parts Local Hills Wolds Top England England is a country that is part of the Castcliffe Hill United Kingdom. It shares land borders Gaumer Hill with Wales to the west and Scotland to the north. Local Rivers River Ancholme River Trent Northern Northern Ireland is a country that is part River Torne Ireland of the United Kingdom River Idle Scotland Scotland is a country that is part of the Local Landmarks Winterton, Thorne Abbey, United Kingdom. Normanby Hall, Elsham Hall Wales Wales is a country that is part of the Compass Points North, East, South West United Kingdom. Key Skills (know how to..) How will I show what I have learnt? Locate the key places (above) on a map and aerial photos Present information knowledgably about the weather Use a compass and use directional language Make a map, using simple symbols Copyright © Crowle Primary Academy/ J. -

Lines Across Lincolnshire Jon Fox Sample 2

2 : TRENT VALLEYS Changing Courses, Gaps & the Ice Age Rivers are one of the most significant linear features in the landscape, previous courses dating to the Ice Age that affected much of southern and both physically and culturally, forming corridors with their own natural central Lincolnshire. At various points in the Trent’s history, its tributaries processes and ecology that have interracted with human societies from the have included the Witham, Till, Slea, Glen and Bain, and even the Welland earliest times. Archaeological remains from over half a million years ago and Nene probably joined it before entering the North Sea until relatively indicate that early hominids used the main river valleys of south-eastern recently (Bridgland, 2014). Today’s Trent, conjoined with the Ouse to form Britain to navigate and colonise the interior of what was then a peninsula of the Humber, receives the River Ancholme and also affects patterns of silt Europe. The ‘Bytham River’, which crossed southern Lincolnshire prior to deposition on Lincolnshire’s coast. In short, very little of Lincolnshire is the Anglian glaciation, is an important example. Later, despite the risk of without some Trent influence on its landscape. flooding, rivers attracted permanent settlement at key crossing and trading 31 points, some of which developed over time into our most important towns. This chapter focuses on the River Trent – including its previous courses through Ancaster and Lincoln – and investigates how the river’s evolution during the Ice Age has influenced the landscape across Lincolnshire. The River Trent is sometimes seen as rather peripheral to Lincolnshire or, at most, as boundary territory with neighbouring counties. -

Display PDF in Separate

E n v ir o n m e n t Ag e n c y NATIONAL LIBRARY & INFORMATION SERVICE ANGLIAN REGION Kingfisher House. Goldhay Way. Orton Goldhay, Peterborough PE2 5ZR En v ir o n m e n t Ag e n c y f o r e wo r d I very much hope you enjoy this, our 2003, Snapshot of the environment in the Anglian Region of the Environment Agency. On the next few pages we look at some of the key indicators of the health of our Region. We can take comfort from the improvements made to river and coastal water quality, air quality, enhanced wildlife and innovative flood defence management. The Anglian Region has a vibrant economy and is a healthy place to live. We are proud of our contribution to the sustainable development of our Region but recognise that we cannot afford to be complacent. We still face daily challenges from pollution incidents and the desire to improve further the biodiversity and quality of our environment. The Anglian Region of the Environment Agency covers a large area and we cross a number of regional Government boundaries. The data that we have used for this year's Snapshot reflects the situation across the whole of the Anglian Region. In 2004 we plan to publish a fuller State of the Environment Report. I look forward to another successful year working with our regional and local partners to deliver an improved environment and a better quality of life for all of us in the Anglian Region. Regional Director snapshot contents The Anglian Region 3 An enhanced environment for wildlife 5 Cleaner air for everyone 7 Improved and protected inland and coastal waters 9 Restored, protected land and healthier soils 11 A greener business world 13 Wiser sustainable use of natural resources 15 Limiting and adapting to climate change 17 Reducing flood risk 19 Conclusions and next steps 21 ENVIRONMENT AGENCY 124245 pages 1 2 5 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 1 3 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 The Anglian Region extends from the Humber estuary in the north to the Thames in the south and from the Norfolk coast in the east to Milton Keynes in the west.