An Institutional Analysis of the Basij-E Mostazafan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PROTESTS and REGIME SUPPRESSION in POST-REVOLUTIONARY IRAN Saeid Golkar

THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY n OCTOBER 2020 n PN85 PROTESTS AND REGIME SUPPRESSION IN POST-REVOLUTIONARY IRAN Saeid Golkar Green Movement members tangle with Basij and police forces, 2009. he nationwide protests that engulfed Iran in late 2019 were ostensibly a response to a 50 percent gasoline price hike enacted by the administration of President Hassan Rouhani.1 But in little time, complaints Textended to a broader critique of the leadership. Moreover, beyond the specific reasons for the protests, they appeared to reveal a deeper reality about Iran, both before and since the 1979 emergence of the Islamic Republic: its character as an inherently “revolutionary country” and a “movement society.”2 Since its formation, the Islamic Republic has seen multiple cycles of protest and revolt, ranging from ethnic movements in the early 1980s to urban riots in the early 1990s, student unrest spanning 1999–2003, the Green Movement response to the 2009 election, and upheaval in December 2017–January 2018. The last of these instances, like the current round, began with a focus on economic dissatisfaction and then spread to broader issues. All these movements were put down by the regime with characteristic brutality. © 2020 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. SAEID GOLKAR In tracking and comparing protest dynamics and market deregulation, currency devaluation, and the regime responses since 1979, this study reveals that cutting of subsidies. These policies, however, spurred unrest has become more significant in scale, as well massive inflation, greater inequality, and a spate of as more secularized and violent. -

Sheikh Qassim, the Bahraini Shi'a, and Iran

k o No. 4 • July 2012 o l Between Reform and Revolution: Sheikh Qassim, t the Bahraini Shi’a, and Iran u O By Ali Alfoneh The political stability of the small island state of Bahrain—home to the US Navy’s Fifth Fleet—matters to the n United States. And Sheikh Qassim, who simultaneously leads the Bahraini Shi’a majority’s just struggle for a more r democratic society and acts as an agent of the Islamic Republic of Iran, matters to the future of Bahrain. A survey e of the history of Shi’a activism in Bahrain, including Sheikh Qassim’s political life, shows two tendencies: reform and t revolution. Regardless of Sheikh Qassim’s dual roles and the Shi’a protest movement’s periodic ties to the regime in Tehran, the United States should do its utmost to reconcile the rulers and the ruled in Bahrain by defending the s civil rights of the Bahraini Shi’a. This action would not only conform to the United States’ principle of promoting a democracy and human rights abroad, but also help stabilize Bahrain and the broader Persian Gulf region and under- mine the ability of the regime in Tehran to continue to exploit the sectarian conflict in Bahrain in a way that broadens E its sphere of influence and foments anti-Americanism. e Every Friday, the elderly Ayatollah Isa Ahmad The Sunni ruling elites of Bahrain, however, l Qassim al-Dirazi al-Bahrani, more commonly see Sheikh Qassim not as a reformer but as d known as Sheikh Qassim, climbs the stairs to the a zealous revolutionary serving the Islamic pulpit at the Imam al-Sadiq mosque in Diraz, d Bahrain, to deliver his sermon. -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 63/Wednesday, April 1, 2020/Notices

18334 Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 63 / Wednesday, April 1, 2020 / Notices DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY a.k.a. CHAGHAZARDY, MohammadKazem); Subject to Secondary Sanctions; Gender DOB 21 Jan 1962; nationality Iran; Additional Male; Passport D9016371 (Iran) (individual) Office of Foreign Assets Control Sanctions Information—Subject to Secondary [IRAN]. Sanctions; Gender Male (individual) Identified as meeting the definition of the Notice of OFAC Sanctions Actions [NPWMD] [IFSR] (Linked To: BANK SEPAH). term Government of Iran as set forth in Designated pursuant to section 1(a)(iv) of section 7(d) of E.O. 13599 and section AGENCY: Office of Foreign Assets E.O. 13382 for acting or purporting to act for 560.304 of the ITSR, 31 CFR part 560. Control, Treasury. or on behalf of, directly or indirectly, BANK 11. SAEEDI, Mohammed; DOB 22 Nov ACTION: Notice. SEPAH, a person whose property and 1962; Additional Sanctions Information— interests in property are blocked pursuant to Subject to Secondary Sanctions; Gender SUMMARY: The U.S. Department of the E.O. 13382. Male; Passport W40899252 (Iran) (individual) Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets 3. KHALILI, Jamshid; DOB 23 Sep 1957; [IRAN]. Control (OFAC) is publishing the names Additional Sanctions Information—Subject Identified as meeting the definition of the of one or more persons that have been to Secondary Sanctions; Gender Male; term Government of Iran as set forth in Passport Y28308325 (Iran) (individual) section 7(d) of E.O. 13599 and section placed on OFAC’s Specially Designated [IRAN]. 560.304 of the ITSR, 31 CFR part 560. Nationals and Blocked Persons List Identified as meeting the definition of the 12. -

The Intelligence Organization of the IRGC: a Major Iranian Intelligence Apparatus Dr

רמה כ ז מל ו תשר מה ו ד י ע י ן ( למ מ" ) רמה כרמ כ ז ז מל מה ו י תשר עד מל מה ו ד ו י ד ע י י ע ן י ן ו רטל ( למ ו מ" ר ) כרמ ז מה י עד מל ו ד י ע י ן ו רטל ו ר The Intelligence Organization of the IRGC: A Major Iranian Intelligence Apparatus Dr. Raz Zimmt November 5, 2020 Main Argument The Intelligence Organization of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) has become a major intelligence apparatus of the Islamic Republic, having increased its influence and broadened its authorities. Iran’s intelligence apparatus, similar to other control and governance apparatuses in the Islamic Republic, is characterized by power plays, rivalries and redundancy. The Intelligence Organization of the IRGC, which answers to the supreme leader, operates alongside the Ministry of Intelligence, which was established in 1984 and answers to the president. The redundancy and overlap in the authorities of the Ministry of Intelligence and the IRGC’s Intelligence Organization have created disagreements and competition over prestige between the two bodies. In recent years, senior regime officials and officials within the two organizations have attempted to downplay the extent of disagreements between the organizations, and strove to present to domestic and foreign audience a visage of unity. The IRGC’s Intelligence Organization (ILNA, July 16, 2020) The IRGC’s Intelligence Organization, in its current form, was established in 2009. The Organization’s origin is in the Intelligence Unit of the IRGC, established shortly after the Islamic Revolution (1979). -

Major General Hossein Salami: Commander-In-Chief of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps October 2020

Major General Hossein Salami: Commander-in-Chief of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps October 2020 1 Table of Contents Salami’s Early Years and the Iran-Iraq War ................................................................................................... 3 Salami’s Path to Power ................................................................................................................................. 4 Commander of the IRGC’s Air Force and Deputy Commander-in-Chief ....................................................... 5 Commander-in-Chief of the IRGC.................................................................................................................. 9 Conclusion ................................................................................................................................................... 11 2 Major General Hossein Salami Major General Hossein Salami has risen through the ranks of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) since its inception after the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran. He served on the battlefield during the Iran-Iraq War, spent part of his career in the IRGC’s academic establishment, commanded its Air Force, served as its second-in-command, and finally was promoted to the top position as commander-in-chief in 2019. Salami, in addition to being an IRGC insider, is known for his speeches, which are full of fire and fury. It’s this bellicosity coupled with his devotion to Iran’s supreme leader that has fueled his rise. Salami’s Early Years and the Iran-Iraq War Hossein -

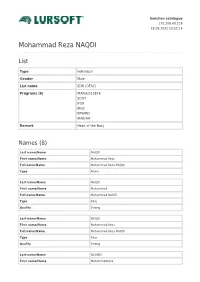

Mohammad Reza NAQDI

Sanction catalogue 170.106.40.219 28.09.2021 10:32:18 Mohammad Reza NAQDI List Type Individual Gender Male List name SDN (OFAC) Programs (6) IRAN-EO13876 SDGT IFSR IRGC NPWMD IRAN-HR Remark Head of the Basij Names (8) Last name/Name NAQDI First name/Name Mohammad Reza Full name/Name Mohammad Reza NAQDI Type Name Last name/Name NAQDI First name/Name Muhammad Full name/Name Muhammad NAQDI Type Alias Quality Strong Last name/Name NAQDI First name/Name Mohammad-Reza Full name/Name Mohammad-Reza NAQDI Type Alias Quality Strong Last name/Name NAGHDI First name/Name Mohammedreza Full name/Name Mohammedreza NAGHDI Type Alias Quality Strong Last name/Name NAQDI First name/Name Gholamreza Full name/Name Gholamreza NAQDI Type Alias Quality Strong Last name/Name NAQDI First name/Name Gholam-reza Full name/Name Gholam-reza NAQDI Type Alias Quality Strong Last name/Name NAGHDI First name/Name Mohammad Reza Full name/Name Mohammad Reza NAGHDI Type Alias Quality Strong Last name/Name SHAMS First name/Name Mohammad Reza Full name/Name Mohammad Reza SHAMS Type Alias Quality Strong Citizenships (1) Country Iran Addresses (1) Country Iran Full address Iran Birth data (6) Birthdate Apr 1961 Birthdate 1951 to 1953 Birthdate 1960 to 1962 Place Tehran, Iran Country Iran Birthdate 1953 Place Najaf, Iraq Country Iraq Identification documents (1) Type Additional Sanctions Information -: Subject to Secondary Sanctions Updated: 28.09.2021. 05:15 The Sanction catalog includes Latvian, United Nations, European Union, United Kingdom and Office of Foreign Assets Control subjects included in sanction list. -

The Grand Strategy of Militant Clients: Iran's Way Of

Security Studies ISSN: 0963-6412 (Print) 1556-1852 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fsst20 The Grand Strategy of Militant Clients: Iran’s Way of War Afshon Ostovar To cite this article: Afshon Ostovar (2018): The Grand Strategy of Militant Clients: Iran’s Way of War, Security Studies To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2018.1508862 Published online: 17 Oct 2018. Submit your article to this journal View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fsst20 SECURITY STUDIES https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2018.1508862 The Grand Strategy of Militant Clients: Iran’s Way of War Afshon Ostovar ABSTRACT This article argues that militant clients should be understood as a pillar of Iran’s grand strategy and an extension of its military power. The article examines why Iran has relied on militant clients since the 1979 revolution and the benefits and costs of its client approach. In evaluating these issues, it iden- tifies five main areas where Iran has gained from its client strategy: 1) maintaining independence from the West; 2) suc- cessfully exporting its religio-political worldview; 3) extending its military reach and power; 4) reducing political costs of its foreign activities; and 5) establishing needed regional allies. It further identifies five main dangers that Iran faces by continu- ing its strategic behavior: 1) increased pressure from the United States and a broader US military regional footprint; 2) more unified regional adversaries; 3) the risk of unintended escalation with the United States and regional adversarial states; and 4) enduring regional instability and insecurity Introduction In the 21st century, no state has had more success in utilizing militant clients outside its borders toward strategic ends than the Islamic Republic of Iran. -

Iran, Gulf Security, and U.S. Policy

Iran, Gulf Security, and U.S. Policy Kenneth Katzman Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs August 14, 2015 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL32048 Iran, Gulf Security, and U.S. Policy Summary Since the Islamic Revolution in Iran in 1979, a priority of U.S. policy has been to reduce the perceived threat posed by Iran to a broad range of U.S. interests, including the security of the Persian Gulf region. In 2014, a common adversary emerged in the form of the Islamic State organization, reducing gaps in U.S. and Iranian regional interests, although the two countries have often differing approaches over how to try to defeat the group. The finalization on July 14, 2015, of a “Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action” (JCPOA) between Iran and six negotiating powers could enhance Iran’s ability to counter the United States and its allies in the region, but could also pave the way for cooperation to resolve some of the region’s several conflicts. During the 1980s and 1990s, U.S. officials identified Iran’s support for militant Middle East groups as a significant threat to U.S. interests and allies. A perceived potential threat from Iran’s nuclear program emerged in 2002, and the United States orchestrated broad international economic pressure on Iran to try to ensure that the program is verifiably confined to purely peaceful purposes. The international pressure contributed to the June 2013 election as president of Iran of the relatively moderate Hassan Rouhani, who campaigned as an advocate of ending Iran’s international isolation. -

Iran - Researched and Compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on 30 December 2011 and 3 January 2012

Iran - Researched and compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on 30 December 2011 and 3 January 2012 Information on the activities of Basij including applicable state support In September 2011 Human Rights Watch states: “Agents of the Ministry of Intelligence, Revolutionary Guards, police, and Basij paramilitaries have been responsible for numerous cases of torture, particularly of political prisoners” (Human Rights Watch (21 September 2011) UN: Expose Iran’s Appalling Rights Record). The European Parliament in November 2011 notes that: “…the Iranian Revolutionary Guard, the secret services and the Basij militia are playing an active role in the severe and brutal repression in Iran.” (European Parliament (17 November 2011) European Parliament resolution of 17 November 2011 on Iran – recent cases of human rights violations) In October 2011 a report by the United States Congressional Research Service points out that: “Iran’s armed forces are divided organizationally. The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC, known in Persian as the Pasdaran) controls the Basij (Mobilization of the Oppressed) volunteer militia that enforces adherence to Islamic customs and has been the main instrument to repress the postelection protests in Iran.” (United States Congressional Research Service (26 October 2011) Iran: U.S. Concerns and Policy Responses, p.25) In March 2011 BBC News notes: “The Revolutionary Guard also controls the Basij Resistance Force, an Islamic volunteer militia of about 90,000 men and woman with an additional capacity to mobilise nearly 1m. The Basij, or Mobilisation of the Oppressed, are often called out onto the streets at times of crisis to use force to dispel dissent. -

ANTI-AMERICANISM Table of Contents Anti-American Statements

ANTI-AMERICANISM Table of Contents Anti-American Statements........................................................................................................... 1 Death to America ..................................................................................................................... 1 America Is The Enemy and Its "Enmity Is Endless" ................................................................. 2 The Great Satan ......................................................................................................................4 Regime’s Goal is to Destroy the United States ........................................................................ 5 America Created ISIS and Al-Qaeda ....................................................................................... 6 U.S. Seeks to Dominate Iran, Islamic Lands, and the World .................................................... 8 Timeline of Anti-American Hostilities ........................................................................................... 8 Iran’s Anti-Western Conspiracies .............................................................................................. 15 The Iranian Regime’s Conspiracies ....................................................................................... 15 The Iranian Regime Prohibits ................................................................................................ 19 Anti-American Statements The Iranian regime has maintained its virulent anti-Americanism as a core pillar of its ideology since -

CPC Outreach Journal #1012

Issue No. 1012, 3 July 2012 Articles & Other Documents: Featured Article: Nuclear Arsenal in China Much Bigger Than Believed , Says Expert 1. China To Lead Talks On Nuclear Definitions 2. China Is ‘Severe’ Nuclear Threat To Taiwan: Expert 3. Nuclear Arsenal in China Much Bigger Than Believed, Says Expert 4. Russian Specialists Involved In Syria Intercepting Turkish Jet, Sources Say 5. Doubts Cast On Turkey's Story Of Jet Dropped By Syria 6. Hezbollah Could Blockade Sea In Future War 7. UN Publishes Report On Iran Arms Trade With Syria 8. US Naval Forces In Region Within Reach Of Iranian Vessels: IRGC Commander 9. Iran: We'll Introduce Missile Against Iron Dome 10. Iran Threatens To Wipe Israel 'Off The Face Of The Earth' 11. China Opposes Unilateral Sanctions Against Iran 12. The Story Behind the Korea-Japan Military Pact 13. Korean Ex-Military Official Warns Of Nuclear Threat From North 14. Panetta Pleads For Missile Defense Dollars Welcome to the CPC Outreach Journal. As part of USAF Counterproliferation Center’s mission to counter weapons of mass destruction through education and research, we’re providing our government and civilian community a source for timely counterproliferation information. This information includes articles, papers and other documents addressing issues pertinent to US military response options for dealing with chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear (CBRN) threats and countermeasures. It’s our hope this information resource will help enhance your counterproliferation issue awareness. Established in 1998, the USAF/CPC provides education and research to present and future leaders of the Air Force, as well as to members of other branches of the armed services and Department of Defense. -

CIG Template

Country Information and Guidance Iran: Background Information, including actors of protection and internal relocation. Version 2.0 December 2015 Preface This document provides general, background information to Home Office decision makers to set the context for considering particular types of protection and human rights claims. Where applicable, it must be read alongside the other country information and guidance material. Decision makers must consider claims on an individual basis, taking into account the case specific facts and all relevant evidence, including: the guidance contained with this document; the available COI; any applicable caselaw; and the Home Office casework guidance in relation to relevant policies. Country Information The COI within this document has been compiled from a wide range of external information sources (usually) published in English. Consideration has been given to the relevance, reliability, accuracy, objectivity, currency, transparency and traceability of the information and wherever possible attempts have been made to corroborate the information used across independent sources, to ensure accuracy. All sources cited have been referenced in footnotes. It has been researched and presented with reference to the Common EU [European Union] Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI), dated April 2008, and the European Asylum Support Office’s research guidelines, Country of Origin Information report methodology, dated July 2012. Feedback Our goal is to continuously improve the guidance and information we provide. Therefore, if you would like to comment on this document, please e-mail us. Independent Advisory Group on Country Information The Independent Advisory Group on Country Information (IAGCI) was set up in March 2009 by the Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration to make recommendations to him about the content of the Home Office‘s COI material.