Chinese Associations and Associational Life in South Africa's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memories of Johannesburg, City of Gold © Anne Lapedus

NB This is a WORD document, you are more than Welcome to forward it to anyone you wish, but please could you forward it by merely “attaching” it as a WORD document. Contact details For Anne Lapedus Brest [email protected] [email protected]. 011 783.2237 082 452 7166 cell DISCLAIMER. This article has been written from my memories of S.Africa from 48 years ago, and if A Shul, or Hotel, or a Club is not mentioned, it doesn’t mean that they didn’t exist, it means, simply, that I don’t remember them. I can’t add them in, either, because then the article would not be “My Memories” any more. MEMORIES OF JOHANNESBURG, CITY OF GOLD Written and Compiled By © ANNE LAPEDUS BREST 4th February 2009, Morningside, Sandton, S.Africa On the 4th February 1961, when I was 14 years old, and my brother Robert was 11, our family came to live in Jhb. We had left Ireland, land of our birth, leaving behind our beloved Grandparents, family, friends, and a very special and never-to-be-forgotten little furry friend, to start a new life in South Africa, land of Sunshine and Golden opportunity…………… The Goldeneh Medina…... We came out on the “Edinburgh Castle”, arriving Cape Town 2nd Feb 1961. We did a day tour of Chapmans Peak Drive, Muizenberg, went to somewhere called the “Red Sails” and visited our Sakinofsky/Yodaiken family in Tamboerskloof. We arrived at Park Station (4th Feb 1961), Jhb, hot and dishevelled after a nightmarish train ride, breaking down in De Aar and dying of heat. -

Chinese Identity in Johannesburg

BURCH FELLOW 2014 CHINESE IDENTITY IN JOHANNESBURG Johannesburg has a reputation sky like a tie-dye thumb. for violent crime. Arriving there, that The concept of Chinese in Africa idea badgered me again and again. surprised me at first, but after seeing I am alone, and Johannesburg has Johannusburg’s color and diversity, a reputation for violent crime. For the idea of two distinct Chinatowns the first part of my trip, ideas of what in the city hardly seemed far- PAUL ASHTON could happen to me if I ventured fetched. I visited the two within my Class of 2015 out, ignorant and alone, paralyzed first week and found them radically Durham, NC me. I spent most of my time different. First Chinatown sits in locked in my one-room apartment downtown Johannesburg, while defied stereotyping. I met a bilingual y Burch on Witwatersrand University’s New Chinatown is located in the preschool teacher and a Jehovah’s project campus, waiting out Human Ethics Cyrildene suburb. On an average witness; a woman whose “Made in challenged M Board approval to start contacting day, First Chinatown is windswept China” tattoo started her career as me to my interviewees. Most nights, I bided and deserted, while New Chinatown a filmmaker; a historian who quit core. It was a success, her job to write a book that took PAUL ASHTONPAUL my time translating local Chinese feels like a bustling street in Beijing. but most of the time, it newspapers with the square head Cantonese versus Mandarin, cultural nine years instead of two; a man didn’t feel that way. -

AG2887-A2-7-001-Jpeg.Pdf

■6-<j- r ' P ^ ^ AFRICANS MOVED AT OUX-POIXT Removals Conducted As Full-Scale Military Operation HNORTHERN EDITIONWRegistered at G.P.O. as a Newspaper JOHANNESBURG.—IN ITS SURPRISE DESCENT ON SOPHIATOWN ON FEB RUARY 9 AND AGAIN LAST TUESDAY THE NATIONALIST GOVERNMENT Vol. I, No. 17 THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 17, 1955 PRICE 3d. MOVED THE FIRST FAMILIES TO MEADOWLANDS—AT GUN-POINT. BE FORE DAWN ON THE 9th, OPERATION GHETTO ROUND-UP STARTED, AS 2,000 POLICE AND THE ARMY CARRIED OUT THEIR SOPHIATOWN MILITARY Op e r a t i o n , t h e i r t a r g e t ?— a f e w h u n d r e d Af r i c a n f a m i l i e s . Such a show of force has probably never been seen before in longer in evidence, and the police South Africa. Not only was Sophiatown thick with armed police relied on their rifles—stacked in drawn from many spots along the Reef, but on the evening of the neat triangles at more than one removal Orlando Power Station was heavily guarded, and armed shop comer—and on assegais and police guards were stationed at intervals all along the route from knobkerries (for the African con Sophiatown to Orlando and through Newclare, past the cemetery stables). and along the main Reef road running past Orlando to guard every Eighty-six military trucks moved MORE cross-road and briilge. All this, no doubt, to act as a fitting back the families, and at 4 a.m. -

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC of SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID-AFRIKA March Vol

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID-AFRIKA March Vol. 585 Pretoria, 7 2014 Maart No. 37395 PART 1 OF 2 LEGAL NOTICES B WETLIKE KENNISGEWINGS SALES IN EXECUTION AND OTHER PUBLIC SALES GEREGTELIKE EN ANDER OPENBARE VERKOPE N.B. The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes AIDS HELPLINEHELPLINE: 08000800-0123-22 123 22 Prevention Prevention is is the the cure cure 400882—A 37395—1 2 No. 37395 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 7 MARCH 2014 IMPORTANT NOTICE The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for faxed documents not received due to errors on the fax machine or faxes received which are unclear or incomplete. Please be advised that an “OK” slip, received from a fax machine, will not be accepted as proof that documents were received by the GPW for printing. If documents are faxed to the GPW it will be the sender’s respon- sibility to phone and confirm that the documents were received in good order. Furthermore the Government Printing Works will also not be held responsible for cancellations and amendments which have not been done on original documents received from clients. TABLE OF CONTENTS LEGAL NOTICES Page SALES IN EXECUTION AND OTHER PUBLIC SALES ................................... 9 Sales in execution: Provinces: Gauteng .......................................................................... 9 Eastern Cape.................................................................. 106 Free State -

11111~111 Iiiii! Ii 9771682452005

Selling price • Verkoopprys: R2,50 Other countries • Buitelands: R3,25 FEBRUARY Vol. 11 PRETORIA, 2 FEBRUARIE 2005 No.32 We all have, the power to prevent AIDS· AIDS HElPUNE 1 oaoo 012 3221 ggle DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH Prevention is the cure. .... ', . ·.· .... 05032 . 11111~111 IIIII! II 9771682452005 J05002727-A 32-1 2 No. 32 PROVINCIAL GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY, 2 FEBRUARY 2005 CONTENTS • INHOUD Page Gazette No. No. No. GENERAL NOTICE 244 Gauteng Liquor Act (2/2003): Applications for liquor licences in terms of section 24: Divided into the following regions: Johannesburg ............................................................. .-........................................... :............................................... 3 32 Tshwane.................................................................................................................................................................. 9 32 Ekurhuleni ................................................................................................. :............................................................. 14 32 Sedibeng................................................................................................................................................................. 18 32 West Rand ............. :................................................................................................................................................ 19 32 Metweding ... ..... ..................... ......................... ....... ......................... ............ .......................... -

Master B Even

AFFILIATED SYNAGOGUES AND MINYANIM Code to Minyanim: 1. All Services 2. Shabbat & Yom Tov 3. All Services except weekday mornings 4. Friday night, Shabbat morning & Yomtov 5. All Shabbat & Yom Tov Services 6. Friday night and Yomtov and Sunday Mornings 8. Shabbat morning and Yomtov 7. Friday nights only 9. Phone for details MASTER B To confirm services and times for commencement, please check by telephoning the relevant number listed. JOHANNESBURG EVEN Congregation Address Rabbi/Contact Telephone Minyanim 166 Blairgowrie 94 Blairgowrie Drive Rabbi S Bacher 011-789-2827 (3) Bnei Akiva 63 Tanced Rd, Glenhazel Rabbi I. Raanan 082-335-2247 (3) Beth Chana 51 Northfield Ave, Glenhazel Rabbi R. Hendler 082-778-7073 (1) (Northfield Shul) Chabad Fourways 24 Campbell St, Ambiance Complex, Rabbi D. Rabin 082-822-6112 (4) Unit 24, Craigavon Chabad Illovo 42 2nd Ave Cnr Central St, Illovo Rabbi M Katz 011-440-6600 (1) Chabad House Shul 27 Aintree Avenue, Savoy Estate Rabbi E. Ash 082-824-9560 (1) Chabad Lyndhurst 133 Morkel Road, Lyndhurst Rabbi A Carlebach 011-882-0303 (1) Chabad Norwood 8 The Avenue, Orchards Rabbi M Rodal 011-728-0655 (5) Chabad Sandton Chabad Place off Hampton Crt, Rabbi J Hecht 011-803-5787 (1) Gallo Manor Cyrildene 32 Aida Avenue Rabbi A. Hoppenstein 082-678-8004 (1) Doornfontein 120 Siemert Road Rabbi I.D. Herrmann 082-683-4100 (4) Jhb continued Congregation Address Rabbi/Contact Telephone Minyanim Edenvale Cnr. 6th Ave & 3rd Street Rabbi Z. Gruzd 011-453-0988 (1) Emmarentia 26 Kei Road, Emmarentia Rabbi H Rosenblum 011-646-6138 (1) Bereshit Great-ParkIsaiah 42 Synagogue Cnr Glenhove & 4th Street, Rabbi D HazdanBereshit Isaiah 42011-728-8152 (1) MASTER A Houghton Estate Greenside 7A Chester Rd, Greenside East Rabbi M Rabinowitz 011-788-5036 (1) Johannesburg Sephardi 58 Oaklands Road, Orchards Rabbi M Kazilsky 011-640-7900 (5) ODD Kensington 80 Orion Street Mr S Jacobs 011-616-4154 (4) Keter Torah 98 10th Ave. -

Jewish Affairs

EEWISHW I S H J Rosh Hashanah A FFFAIRSFA I R S 2013 Price R50,00 incl. VAT Registered at the GPO as a Newspaper ISSN 0021 • 6313 Specialist Banking Asset Management Wealth & Investment INSIDE FRONT COVER FRONT INSIDE MISSION EDITORIAL BOARD In publishing JEWISH AFFAIRS, the SA EXECUTIVE EDITOR Jewish Board of Deputies aims to produce a cultural forum which caters for a wide David Saks SA Jewish Board of Deputies variety of interests in the community. The journal will be a vehicle for the publication of ACADEMIC ADVISORY BOARD articles of significant thought and opinion on Professor Marcus Arkin contemporary Jewish issues, and will aim to encourage constructive debate, in the form of Suzanne Belling reasoned and researched essays, on all matters Dr Louise Bethlehem Hebrew University of Jerusalem of Jewish and general interest. Marlene Bethlehem SA Jewish Board of Deputies Cedric Ginsberg University of South Africa JEWISH AFFAIRS aims also to publish essays Dr Elaine Katz of scholarly research on all subjects of Jewish Professor Marcia Leveson interest, with special emphasis on aspects of South African Jewish life and thought. Naomi Musiker Archivist and Bibliographer Scholarly research papers that make an original Professor Reuben Musiker SAJBD Library Consultant contribution to their chosen field of enquiry Gwynne Schrire SA Jewish Board of Deputies will be submitted to the normal processes of Dr Gabriel A Sivan World Jewish Bible Centre academic refereeing before being accepted Professor Gideon Shimoni Hebrew University of Jerusalem for publication. Professor Milton Shain University of Cape Town JEWISH AFFAIRS will promote Jewish John Simon cultural and creative achievement in South Mervyn Smith Africa, and consider Jewish traditions and The Hon. -

South African Architectural Record

SOUTH AFRICAN ARCHITECTURAL RECORD THE JOURNAL OF THE CAPE, NATAL, ORANGE FREE STATE AND TRANSVAAL PROVINCIAL INSTITUTES OF SOUTH AFRICAN ARCHITECTS AND THE CHAPTER OF SOUTH AFRICAN QUANTITY SURVEYORS M T im FOR DECEMBER 1019 RESIDENCE IN CYRILDENE, JOHANNESBURG. Jacques Morgenstern, Architect 250 HOUSE FISHER, GREENSIDE, JOHANNESBURG, Axelrod and Siew; Gilbert Herbert, Associated Architects 254 HOUSE RABBIE, GREENSIDE, JOHANNESBURG. Gilbert Herbert, Architect 256 A LETTER FROM ANTHONY CHITTY 259 CONTEMPORARY JOURNALS 262 OBITUARY : Donald Ele Pilcher 264 BOOK REVIEWS 265 NOTES AND NEW S 266 EDITOR VOLUME 34 The Editor will be glad to consider any MSS., photographs or sketches submitted to him, but they should be accompanied by stamped addressed envelopes for return if W. DUNCAN HOWIE unsuitable. In case of loss or injury he cannot hold himself responsible for MSS., photographs or sketches, and publication in the Journal can alone be taken as evidence ASSISTANT EDITORS of acceptance. The name and address of the owner should be placed on the back of UGO T O M A S E L L I all pictures and MSS. The Institute does not hold itself responsible for the opinions 12 expressed by contributors. Annual subscription £1 I Os. direct to the Secretary, GILBERT HERBERT 612, KELVIN HOUSE, 75. MARSHALL STREET. JOHANNESBURG. ’PHONE 34-2921. BUSINESS MANAGEMENT: G. J. McHARRY (PTY.), LTD., 43, BECKETT’S BUILDINGS, JOHANNESBURG, P.O. BOX 1409, ’PHONE 33-7505. RESIDENCE IN CYRILDENE, JOHANNESBURG JACQUES MORGENSTERN, ARCHITECT The house stands on a steeply sloping, nearly triangular plot with two of its sides facing streets which meet at an acute angle. -

Strategic Integrated Transport Plan Framework for the Ci Ty of Johannesburg

STRATEGIC INTEGRATED TRANSPORT PLAN FRAMEWORK FOR THE CI TY OF JOHANNESBURG FINAL 30 AUGUST 2013 CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 3 City and Transport Facts and Figures ............................................................................................ 5 Johannesburg Demographics ................................................................................................. 5 Transport System in Johannesburg........................................................................................ 6 Travel Behaviour, Characteristics and Attitudes in Johannesburg ...................................... 16 Changes in Johannesburg Transport System Over the Last Ten Years ................................ 18 The Strategic Public Transport Network (SPTN) Proposals and Phase 1A, 1B and 1C of the Rea Vaya BRT Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) System .......................................................... 18 Gautrain Implementation ................................................................................................ 25 Using Transport Corridors to Restructure the City .......................................................... 26 Upgrade of Heavy Rail Corridors in Joburg ...................................................................... 29 Susidised Bus Contracts Rationalisation .......................................................................... 31 Minibus-taxi network Re-organisation and Legalisation ................................................ -

Netflorist Designated Area List.Pdf

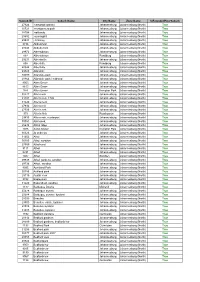

Subrub ID Suburb Name City Name Zone Name IsExtendedHourSuburb 27924 carswald kyalami Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 30721 montgomery park Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 28704 oaklands Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 28982 sunninghill Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 29534 • bramley Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 8736 Abbotsford Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 28048 Abbotts ford Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 29972 Albertskroon Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 897 Albertskroon Randburg Johannesburg (North) True 29231 Albertsville Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 898 Albertville Randburg Johannesburg (North) True 28324 Albertville Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 29828 Allandale Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 30099 Allandale park Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 28364 Allandale park / midrand Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 9053 Allen Grove Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 8613 Allen Grove Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 974 Allen Grove Kempton Park Johannesburg (North) True 30227 Allen neck Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 31191 Allen’s nek, 1709 Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 31224 Allens neck Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 27934 Allens nek Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 27935 Allen's nek Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 975 Allen's Nek Roodepoort Johannesburg (North) True 29435 Allens nek, rooderport Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 30051 Allensnek, Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 28638 -

Gauteng Johannesburg Main Seat of Johannesburg Central Magisterial

# # !C # # # ## ^ !C# !.!C# # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # ^!C # # # # # ^ # # # # ^ !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # # !C!C # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # !C# # # # # # !C # ^ # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # !C # # !C # #^ # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # ## # !C # # # # # !C # # # # # # # #!C # !C # # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # !C # # ^ # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # ##^ !C # !C# # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # ## # # # #!C # !C# # # ##!C # # # # # # # # !C# # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # ## ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # !C ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ^ !C # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C !C # # # # # # # # !C # # #!C # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # ### !C # # !C # # # # !C # ## ## ## !C # # !C # !. # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # !C # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # ### # # # # # # # # # # !C ## # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # !C !C### # # # ## # !C # # # # # !C# # # # # # # !C # # # # !C # ^ # # # !C # ^ # # ## !C # # # !C #!C ## # # # # # # ## # # # # # ## # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # -

A Green Infrastructure Planning Approach in the Gauteng City-Region

GCRO RESEARCH REPORT # NO. 04 A FRAMEWORK FOR A GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE PLANNING APPROACH IN THE GAUTENG CITY-REGION SEPTEMBER 2016 Written by Christina Culwick and Kerry Bobbins, with contributions from Anton Cartwright and Gregg Oelofse, Myles Mander, and Stuart Dunsmore A PARTNERSHIP OF A FRAMEWORK FOR A GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE PLANNING APPROACH IN THE GCR September 2016 ISBN: 978-0-620-72851-5 Copyright 2016 © Gauteng City-Region Observatory Written by: Christina Culwick and Kerry Bobbins, with Published by the Gauteng City-Region Observatory contributions from Anton Cartwright and Gregg Oelofse, (GCRO), a partnership of the University of Myles Mander, and Stuart Dunsmore Johannesburg, the University of the Witwatersrand, Design: Breinstorm Brand Architects Johannesburg, the Gauteng Provincial Government Cover Image: Brenden Gray and organised local government in Gauteng. A framework for a green infrastructure planning approach in the Gauteng City-Region ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: This report would not have been possible without the discussions in GCRO’s Green Infrastructure CityLab in 2014 and 2015. We would particularly like to thank those local and provincial government officials, academics and representatives of other stakeholder groups who were part of these discussions, and contributed their time, insights and experience, in particular: Theo Bernhardt, Stephan Du Toit, Jane Eagle, Anne Fitchett, Budu Manaka, Mokgema Mongane, Timothy Nast, Thembeka Nxumalo, Susan Stoffberg, Mahlodi Tau and Elsabeth van der Merwe. We also acknowledge the financial contribution to the project by the Department of Science and Technology and the National Research Foundation, as part of the programme “Urban Resilience Assessment for Sustainable Urban Development” at the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits).