ZIMBABWE Report of the Fact-Finding Mission June 2002

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mortal Remains: Succession and the Zanu Pf Body Politic

THE MORTAL REMAINS: SUCCESSION AND THE ZANU PF BODY POLITIC Report produced for the Zimbabwe Human Rights NGO Forum by the Research and Advocacy Unit [RAU] 14th July, 2014 1 CONTENTS Page No. Foreword 3 Succession and the Constitution 5 The New Constitution 5 The genealogy of the provisions 6 The presently effective law 7 Problems with the provisions 8 The ZANU PF Party Constitution 10 The Structure of ZANU PF 10 Elected Bodies 10 Administrative and Coordinating Bodies 13 Consultative For a 16 ZANU PF Succession Process in Practice 23 The Fault Lines 23 The Military Factor 24 Early Manoeuvring 25 The Tsholotsho Saga 26 The Dissolution of the DCCs 29 The Power of the Politburo 29 The Powers of the President 30 The Congress of 2009 32 The Provincial Executive Committee Elections of 2013 34 Conclusions 45 Annexures Annexure A: Provincial Co-ordinating Committee 47 Annexure B : History of the ZANU PF Presidium 51 2 Foreword* The somewhat provocative title of this report conceals an extremely serious issue with Zimbabwean politics. The theme of succession, both of the State Presidency and the leadership of ZANU PF, increasingly bedevils all matters relating to the political stability of Zimbabwe and any form of transition to democracy. The constitutional issues related to the death (or infirmity) of the President have been dealt with in several reports by the Research and Advocacy Unit (RAU). If ZANU PF is to select the nominee to replace Robert Mugabe, as the state constitution presently requires, several problems need to be considered. The ZANU PF nominee ought to be selected in terms of the ZANU PF constitution. -

Zimbabwe's Power Sharing Government and the Politics Of

Creating African Futures in an Era of Global Transformations: Challenges and Prospects Créer l’Afrique de demain dans un contexte de transformations mondialisées : enjeux et perspectives Criar Futuros Africanos numa Era de Transformações Globais: Desafios e Perspetivas بعث أفريقيا الغد في سياق التحوﻻت المعولمة : رهانات و آفاق Toward more democratic futures: making governance work for all Africans Zimbabwe’s Power Sharing Government and the Politics of Economic Indigenisation, 2009 to 2013 Musiwaro Ndakaripa Toward more democratic futures: making governance work for all Africans Zimbabwe’s Power Sharing Government and the Politics of Economic Indigenisation, 2009 to 2013 Abstract Using the economic indigenisation policy this study examines the problems caused by Zimbabwe‟s power sharing government (PG) to democratic governance between 2009 and 2013. The power sharing government experienced policy gridlock in implementing the Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment Act of 2007 due to disagreements among the three governing political parties which were strategising to gain political credibility and mobilising electoral support to ensure political survival in the long term. The Indigenisation Act intends to give indigenous black Zimbabweans at least fifty one per cent (51%) shareholding in all sectors of the economy. The Zimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) posited that economic indigenisation rectifies colonial imbalances by giving black Zimbabweans more control and ownership of the nation‟s natural resources and wealth. The two Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) political parties in the power sharing government asserted that while economic indigenisation is a noble programme, it needs revision because it discouraged Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). Moreover, the two MDC parties claimed that economic indigenisation is a recipe for ZANU-PF elite enrichment, clientelism, cronyism, corruption and political patronage. -

OTHER ISSUES ANNEX E: MDC CANDIDATES & Mps, JUNE 2000

Zimbabwe, Country Information Page 1 of 95 ZIMBABWE COUNTRY REPORT OCTOBER 2003 COUNTRY INFORMATION & POLICY UNIT I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT II GEOGRAPHY III ECONOMY IV HISTORY V STATE STRUCTURES VIA HUMAN RIGHTS ISSUES VIB HUMAN RIGHTS - SPECIFIC GROUPS VIC HUMAN RIGHTS - OTHER ISSUES ANNEX A: CHRONOLOGY ANNEX B: POLITICAL ORGANISATIONS ANNEX C: PROMINENT PEOPLE PAST & PRESENT ANNEX D: FULL ELECTION RESULTS JUNE 2000 (hard copy only) ANNEX E: MDC CANDIDATES & MPs, JUNE 2000 & MDC LEADERSHIP & SHADOW CABINET ANNEX F: MDC POLICIES, PARTY SYMBOLS AND SLOGANS ANNEX G: CABINET LIST, AUGUST 2002 ANNEX H: REFERENCES TO SOURCE MATERIAL 1. SCOPE OF THE DOCUMENT 1.1 This country report has been produced by the Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a wide variety of recognised sources. The document does not contain any Home Office opinion or policy. 1.2 The country report has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum / human rights determination process. The information it contains is not exhaustive. It concentrates on the issues most commonly raised in asylum / human rights claims made in the United Kingdom. 1.3 The country report is sourced throughout. It is intended to be used by caseworkers as a signpost to the source material, which has been made available to them. The vast majority of the source material is readily available in the public domain. 1.4 It is intended to revise the country report on a six-monthly basis while the country remains within the top 35 asylum-seeker producing countries in the United Kingdom. -

ZIMBABWE COUNTRY REPORT April 2004

ZIMBABWE COUNTRY REPORT April 2004 COUNTRY INFORMATION & POLICY UNIT IMMIGRATION & NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM Zimbabwe April 2004 CONTENTS 1 Scope of the Document 1.1 –1.7 2 Geography 2.1 – 2.3 3 Economy 3.1 4 History 4.1 – 4.193 Independence 1980 4.1 - 4.5 Matabeleland Insurgency 1983-87 4.6 - 4.9 Elections 1995 & 1996 4.10 - 4.11 Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) 4.12 - 4.13 Parliamentary Elections, June 2000 4.14 - 4.23 - Background 4.14 - 4.16 - Election Violence & Farm Occupations 4.17 - 4.18 - Election Results 4.19 - 4.23 - Post-election Violence 2000 4.24 - 4.26 - By election results in 2000 4.27 - 4.28 - Marondera West 4.27 - Bikita West 4.28 - Legal challenges to election results in 2000 4.29 Incidents in 2001 4.30 - 4.58 - Bulawayo local elections, September 2001 4.46 - 4.50 - By elections in 2001 4.51 - 4.55 - Bindura 4.51 - Makoni West 4.52 - Chikomba 4.53 - Legal Challenges to election results in 2001 4.54 - 4.56 Incidents in 2002 4.57 - 4.66 - Presidential Election, March 2002 4.67 - 4.79 - Rural elections September 2002 4.80 - 4.86 - By election results in 2002 4.87 - 4.91 Incidents in 2003 4.92 – 4.108 - Mass Action 18-19 March 2003 4.109 – 4.120 - ZCTU strike 23-25 April 4.121 – 4.125 - MDC Mass Action 2-6 June 4.126 – 4.157 - Mayoral and Urban Council elections 30-31 August 4.158 – 4.176 - By elections in 2003 4.177 - 4.183 Incidents in 2004 4.184 – 4.191 By elections in 2004 4.192 – 4.193 5 State Structures 5.1 – 5.98 The Constitution 5.1 - 5.5 Political System: 5.6 - 5.21 - ZANU-PF 5.7 - -

Zimbabwe: the Face of Torture and Organised Violence

REDRESS ZIMBABWE: THE FACE OF TORTURE AND ORGANISED VIOLENCE Torture and Organised Violence in the run-up to the 31 March 2005 General Parliamentary Election THE REDRESS TRUST MARCH 2005 ZIMBABWE: THE FACE OF TORTURE AND ORGANISED VIOLENCE Torture and Organised Violence in the run-up to the 31 March 2005 General Parliamentary Election March 2005 THE REDRESS TRUST 3rd Floor, 87 Vauxhall Walk, London SE11 5HJ Tel: +44 (0)20 7793 1777 Fax: +44 (0)20 7793 1719 Registered Charity Number 1015787, A Limited Company in England Number 2274071 [email protected] (general correspondence) URL: www.redress.org 2 INDEX 1. INTRODUCTION ................................ ................................ ....................... 1 CASE STUDY ONE .................................................................................. 3 2. ZIMBABWE’S DETERIORATING HUMAN RIGHTS RECORD................ 4 3. TORTURE AND ORGANISED VIOLENCE ................................ ................ 5 CASE STUDY TWO ................................................................................. 6 4. TORTURE, ORGANISED VIOLENCE AND ELECTIONS.......................... 8 CASE STUDY THREE............................................................................. 10 CASE STUDY FOUR .............................................................................. 11 5. THE ZANU-PF PRIMARY ELECTIONS AND POLITICAL VIOLENCE .. 13 CASE STUDY FIVE................................................................................ 13 6. THE FORTHCOMING ELECTIONS: CAN THEY BE FREE AND FAIR? 15 CASE -

Zimbabwe: in Search of a New Strategy

ZIMBABWE: IN SEARCH OF A NEW STRATEGY 19 April 2004 ICG Africa Report N°78 Nairobi/Brussels TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS ....................................................... i I. THE EVER DEEPENING CRISIS............................................................................... 1 A. THE ECONOMY’S COLLAPSE .................................................................................................2 B. DETERIORATING GOVERNANCE ............................................................................................3 1. Press freedoms ...........................................................................................................3 2. Political violence .......................................................................................................4 3. Civic freedoms...........................................................................................................5 4. Crackdown on corruption: Political scapegoating .....................................................6 II. MUGABE'S VICTORY ................................................................................................. 7 A. ZANU-PF: IN SEARCH OF LEGITIMACY................................................................................7 B. THE MDC: IN SEARCH OF A STRATEGY ................................................................................8 III. TALKS ABOUT TALKS............................................................................................. 10 A. THE PARTIES.......................................................................................................................10 -

Building and Urban Planning in Zimbabwe with Special Reference to Harare: Putting Needs, Costs and Sustainability in Focus

Consilience: The Journal of Sustainable Development Vol. 11, Iss. 1 (2014), Pp. 1–26 Building and Urban Planning in Zimbabwe with Special Reference to Harare: Putting Needs, Costs and Sustainability in Focus Innocent Chirisa, PhD Department of Rural & Urban Planning University of Zimbabwe Abstract This article examines construction and its relationship with urban planning in Zimbabwe. Urban planning has been blamed for making the building process cumbersome, thereby raising transaction costs. Such transaction costs include planning and associated bureaucratic processes, which are often underestimated by construction investors. Although planning is critical for the sustainability of buildings in Zimbabwe, it still relies heavily on outdated building standards set by the British. The social, economic, and physical environment in which construction takes place has greatly changed. Issues concerning costs, investments, building materials, planning laws, and climate change play a key role in shaping urban environments. They are thus examined in the context of sustainable construction, a field of science that addresses relevant societal needs and issues of technology. This article is a theoretical and empirical review of the present needs and costs characterizing the construction industry. It examines both micro and macro-scale building processes and issues raised by different players in the industry. Can sustainability be achieved with the current mantra of building operations, guided by the present planning diktats and procedures? Keywords: town planning, standards, transaction costs, urban policy, economic meltdown, sustainability 2 Consilience 1. Introduction This article examines construction and its relationship with urban planning in Zimbabwe. Urban planning has encumbered the building process, elevating the costs of development in the form of transaction costs. -

Zimbabwe April 2002

Zimbabwe Country Report October 2003 Country Information and Policy Unit Immigration and Nationality Directorate Home Office, United Kingdom Zimbabwe October 2003 CONTENTS 1 Scope of the Document 1.1 - 1.4 2 Geography 2.1 - 2.3 3 Economy 3.1 4 History 4.1 - 4.175 Independence 1980 4.1 - 4.5 Matabeleland Insurgency 1983-87 4.6 - 4.9 Elections 1995 & 1996 4.10 - 4.11 Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) 4.12 - 4.13 Parliamentary Elections, June 2000 4.14 - 4.23 - Background 4.14 - 4.16 - Election Violence & Farm Occupations 4.17 - 4.18 - Election Results 4.19 - 4.23 - Post-election Violence 2000 4.24 - 4.27 - By election results in 2000 4.28 - 4.29 - Marondera West 4.28 - Bikita West 4.29 - Legal challenges to election results in 2000 4.30 Incidents in 2001 4.31 - 4.58 - Bulawayo local elections, September 2001 4.48 - 4.52 - By elections in 2001 4.53 - 4.55 - Bindura 4.53 - Makoni West 4.54 - Chikomba 4.55 - Legal Challenges to election results in 2001 4.56 - 4.58 Incidents in 2002 4.59 - 4.94 - Presidential Election, March 2002 4.59 - 4.68 - Background 4.69 - 4.81 - Election Result 4.69 - 4.72 - Rural elections September 2002 4.73 - 4.81 - By election results in 2002 4.82 - 4.89 - Hurungwe West 4.90 - 4.93 - Insiza 4.90 - Kuwadzana 4.91 - Highfield 4.92 - Legal challenges to election results in 2002 4.93 Incidents in 2003 4.94 - Mass Action 18-19 March 2003 4.95 - 4.112 - ZCTU strike 23-25 April 4.113 - 4.129 - MDC Mass Action 2-6 June 4.130 - 4.147 - Mayoral and Urban Council elections 30-31 August 4.148 - 4.164 - Mayor of Harare 4.165 -

Zimbabwe in Turmoil and Tenacity

ZIMBABWE: IN SEARCH OF A NEW STRATEGY 19 April 2004 ICG Africa Report N°78 Nairobi/Brussels TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS ....................................................... i I. THE EVER DEEPENING CRISIS............................................................................... 1 A. THE ECONOMY’S COLLAPSE .................................................................................................2 B. DETERIORATING GOVERNANCE ............................................................................................3 1. Press freedoms ...........................................................................................................3 2. Political violence .......................................................................................................4 3. Civic freedoms...........................................................................................................5 4. Crackdown on corruption: Political scapegoating .....................................................6 II. MUGABE'S VICTORY ................................................................................................. 7 A. ZANU-PF: IN SEARCH OF LEGITIMACY................................................................................7 B. THE MDC: IN SEARCH OF A STRATEGY ................................................................................8 III. TALKS ABOUT TALKS............................................................................................. 10 A. THE PARTIES.......................................................................................................................10 -

Informality and Governmentality: an Ethnography of Conversion Entrepreneurship in Harare

Informality and Governmentality: An Ethnography of Conversion Entrepreneurship in Harare by Robert Nyakuwa Dissertation presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Social Anthropology in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Prof C.S. Van der Waal March 2018 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third-party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. March 2018 Copyright © 2018 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved i Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Acknowledgements The co-production of this work has taken a very long time and has involved many people. Although I claim authorship by attaching my name on the front cover there are many people, some of whom I shall name below that have helped shape the ideas and generated the intellectual insights outlined in the pages that make up this thesis. The individuals I acknowledge below are not in any hierarchical order but simply outlined according to my recall of their contribution to my work. I am greatly indebted to Bert Helmsing (local economic development and entrepreneurship), Georgina Gomez (informality and alternative currencies), Peter Knoringa (value chains and enterprise development), John Cameron (research epistemologies and visual ethnography), Karin Astrid Siegman (informality, radical epistemologies and development economics) and Des Gasper (discourse analysis). -

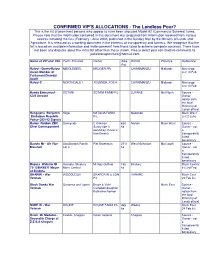

CONFIRMED VIP's ALLOCATIONS - the Landless Poor? This Is the List of Prominent Persons Who Appear to Have Been Allocated Model A2 (Commercial Scheme) Farms

CONFIRMED VIP'S ALLOCATIONS - The Landless Poor? This is the list of prominent persons who appear to have been allocated Model A2 (Commercial Scheme) farms. Please note that the information contained in this document was prepared from information received from various sources including the lists (February / June 2002) published in the Sunday Mail by the Ministry of Lands and Agriculture. It is released as a working document in the interests of transparency and fairness. We recognise that the list is based on available information and invite comment from those listed to achieve complete accuracy. There have not been any disputes about the initial list other than those shown. Please direct your constructive comments to [email protected] Name of VIP and title Farm/ Province Owner Area District Province Reference (ha) Baloyi - Query-Baloyi MIDDLEDEEL KRUGER PR CHIRUMANZU Midlands Masvingo Aaron Member of List 10 Feb ParliamentChiredzi South Baloyi C NORTHDALE 1 JOURNER J DE K CHIRUMANZU Midlands Masvingo List 10 Feb Banda Emmanuel - SOTANI SOTANI FARM P/L LUPANE Mat North Source - Civil Servant Owner - notice from the local Mininstry of Lands official Bangajena Benjamin Silgo NATALIA FARM Makonde Mash West Zimbabwe Republic P/L List 2 June Police CID HO Signals Barwe Reuben ZBC Sunnyside C Kirkman 830 Norton Mash West Source - Chief Correspondent Sunnyside is ha Owner - not owned by Kevana a Investments transparently listed beneficiary Basutu Mr - Air Vice Swallowfork Ranch Piet Broekman 2711 West Nicholson Mat south Source - Marshall Lot 3 ha Owner - not a transparently listed beneficiary Bepura Webster ID Avondur, Bindura Mr Roy Guthrie 150 Bindura Mash Central 75-129849D71 Mayor Mash Central ha list 3rd Feb of Bindura BHARIRI - War WOODLEIGH DRAPER W & SON HARARE Mash East Veteran P/L 24 Feb list Black Ganda War Gorajena and Igava Bruce & Vicki Mash East Source - Veteran Campbell daughter Owner - Katharine Reimer. -

Zimbabwe April 2002

ZIMBABWE COUNTRY REPORT October 2004 COUNTRY INFORMATION AND POLICY UNIT IMMIGRATION AND NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM Zimbabwe Oct 2004 Contents 1. Scope of the Document 1.1–1.10 2. Geography 2.1–2.4 3. Economy 3.1–3.4 4. History 4.1–4.95 Post-Independence 4.5 Matabeleland Insurgency 1983–87 4.6 Political Developments 4.7–4.9 Recent History 4.10–4.11 Parliamentary Elections, June 2000 4.12–4.13 Presidential Election, March 2002 4.14–4.16 Land Reform 4.17–4.19 Sanctions and Commonwealth Suspension 4.20–4.23 2002 Incidents of Political Violence and Intimidation 4.24–4.31 2003 Incidents of Political Violence and Intimidation 4.32–4.36 2004 Incidents of Political Violence and Intimidation 4.37–4.50 History of Local and By-elections By-elections in 2000 4.51–4.52 Bulawayo Local Elections, September 2001 4.53–4.56 By-elections in 2001 4.57–4.59 Rural Elections, September 2002 4.60–4.66 By-elections in 2002 4.67–4.68 Mayoral and Urban Council Elections, 30-31 August 2003 4.69–4.86 By-elections in 2003 4.87–4.92 By-elections in 2004 4.93–4.95 5. State Structures 5.1–5.81 The Constitution 5.1–5.3 Citizenship and Nationality 5.4 Political System 5.5–5.6 Parliament 5.7–5.14 Judiciary 5.15–5.27 Legal Rights/Detention 5.28–5.35 Death Penalty 5.36 Internal Security 5.37–5.43 Prisons and Prison Conditions 5.44–5.52 Military Service 5.53–5.55 Medical Services 5.56–5.60 People with Disabilities 5.61–5.64 HIV/AIDS 5.65–5.75 Education System 5.76–5.81 6.