©Ferrata Storti Foundation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bitamoazedthesis.Pdf (2.274Mb)

GASTROINTESTINAL ABSORPTION OF HEPARINS A Dissertation Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillments of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate Program of Veterinary Biomedical Sciences University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon Bita Moazed Copyright Bita Moazed, November 2009. All Rights Reserved PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this dissertation in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Doctor of Philosophy degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis/dissertation in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by Dr. Linda M. Hiebert who supervised my dissertation work or, in her absence, by the chair of the Graduate Program of Veterinary Biomedical Sciences. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this dissertation or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in this dissertation. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of other material in this dissertation in whole or part should be addressed to: Chair of the Graduate Program of Veterinary Biomedical Sciences Western College of Veterinary Medicine University of Saskatchewan 52 Campus Drive Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5B4 Canada i PREFACE This dissertation has been organized as a series of manuscripts that was or will be submitted for publication in scientific journals. -

Review of Anticoagulant Drugs in Paediatric Thromboembolic Disease

18th Expert Committee on the Selection and Use of Essential Medicines (21 to 25 March 2011) Section 12: Cardiovascular medicines 12.5 Antithrombotic medicines Review of Anticoagulant Drugs in Paediatric Thromboembolic Disease September 2010 Prepared by: Fiona Newall Anticoagulation Nurse Manager/ Senior Research Fellow Royal Children’s Hospital/ The University of Melbourne Melbourne, Australia 1 Contents Intent of Review Review of indications for antithrombotic therapy in children Venous thromboembolism Arterial thrombeombolism Anticoagulant Drugs Unfractionated heparin Mechanism of action and pharmacology Dosing and administration Monitoring Adverse events Formulary Summary recommendations Vitamin K antagonists Mechanism of action and pharmacology Dosing and administration Monitoring Adverse events Formulary Summary recommendations Low Molecular Weight Heparins Mechanism of action and pharmacology Dosing and administration Monitoring Adverse events Formulary Summary recommendations ??Novel anticoagulants Summary 2 1. Intent of Review To review the indications for anticoagulant therapies in children. To review the epidemiology of thromboembolic events in children. To review the literature and collate the evidence regarding dosing, administration and monitoring of anticoagulant therapies in childhood. To review the safety of anticoagulant therapies and supervision required To give recommendations for the inclusion of anticoagulants on the WHO Essential Medicines List 2. Review of indications for antithrombotic therapy in children Anticoagulant therapies are given for the prevention or treatment of venous and/or arterial thrombosis. The process of ‘development haemostasis’, whereby the proteins involved in coagulation change quantitatively and qualitatively with age across childhood, essentially protects children against thrombosis(1-5). For this reason, insults such as immobilization are unlikely to trigger the development of thrombotic diseases in children. -

For National Autllority Use Only

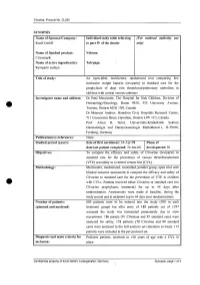

Clivarine. Protocol No. CL055 SYNOPSIS Name of Sponsor/Company: Individual study table referring (For national autllOrity use Knoll GmbH to part IV of the dossier only) Name of finished product: Volume: Clivarine® Name of active ingredient(s): Tab/page: Reviparin sodium Title of study: An open-label, multicentre, randomized trial comparing low molecular weight heparin (reviparin) to standard care for the prophylaxis of deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism in children with central venous catheters Investigator name and address: Dr Patti Massicotte, The Hospital for Sick Children, Division of Hematology/Oncology, Room 9420, 555 University Avenue, Toronto, Ontario M5G JX8, Canada Dr Maureen Andrew, Hamilton Civic Hospitals Research Center, 711 Concession Street, Hamilton, Ontario L8V JC3, Canada Prof. Anton H. Sutor, Universitats-Kinderklink Sektion Haematologie und Haemostaseologie Mathildenstr.l, D-79106, Freiburg, Germany Publication(s) (reference): None. Studied period (years): date of first enrolment: 24-Apr-98 Phase of date' last patient completed: 24-Jan-00 development: 111 Objectives: To compare the efficacy and safety of Clivarine (reviparin) to standard care for the prevention of venous thromboembolism (VTE) secondary to a central venous line (CVL). Methodology: Multicentre, randomized, controlled, parallel group, open trial with blinded outcome assessment to compare the efficacy and safety of Clivarine to standard care for the prevention of VTE in children e· with CVLs. Patients received either Clivarine or standard care (no -

Anderson Chapt 8

Chapter-8 Bibliography Where is the evidence? Literature Cited Alpert JS, Dalen JE. Epidemiology and natural history of venous thromboembo- lism. Prog Cardiovas Dis 1994; 36:417-22. Anderson FA, Wheeler HB, Golberg RJ, Hosmer DW, Forcier A, Patwardhan NA. Changing clinical practice: Prospective study of the impact of continuing medical education and quality assurance programs on use of prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism Arch Intern Med 1994; 154:669-677. Anderson FA Jr, Wheeler HB, Goldberg RJ, Hosmer DW, Forcier A, Patwardhan NA. Physician practices in the prevention of venous thromboembolism. Ann Intern Med 1991;115:591-595. Anderson FA Jr, Wheeler HB. Strategies to improve implementation. In: Goldhaber S, ed. Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker Inc.; 1992; 519-539. Bergqvist D. 1983. Post-operative Thromboembolism, Frequency, Etiology, Prophylaxis. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. Clagett GP, Anderson FA Jr, Heit J, Levine MN, Wheeler HB. Prevention of venous thromboembolism. Chest 1995; 108:312S-334S. Collins R, Scrimgeour A, Yusuf S, et al. Reduction in fatal pulmonary embolism and venous thrombosis by perioperative administration of subcutaneous heparin. N Engl J Med 1988; 318:1162-73. Gallus AS. Anticoagulants in the prevention of venous thromboembolism. Baillieres Clin Haematol 1990; 3(3):651-684. Hull RD, Raskob GE, Hirsh J. The diagnosis of clinically suspected pulmonary embolism: Practical approaches. Chest 1986; 89(5 Suppl):417S-425S. Morrell MP, Dunhill MA. The postmortem incidence of pulmonary embolism in a hospital population. Br J Surg 1968; 55:347-352. NIH Consensus Development. Prevention of venous thrombosis and pulmonary Best embolism. JAMA 1986; 256:744-749. -

Patent Application Publication ( 10 ) Pub . No . : US 2019 / 0192440 A1

US 20190192440A1 (19 ) United States (12 ) Patent Application Publication ( 10) Pub . No. : US 2019 /0192440 A1 LI (43 ) Pub . Date : Jun . 27 , 2019 ( 54 ) ORAL DRUG DOSAGE FORM COMPRISING Publication Classification DRUG IN THE FORM OF NANOPARTICLES (51 ) Int . CI. A61K 9 / 20 (2006 .01 ) ( 71 ) Applicant: Triastek , Inc. , Nanjing ( CN ) A61K 9 /00 ( 2006 . 01) A61K 31/ 192 ( 2006 .01 ) (72 ) Inventor : Xiaoling LI , Dublin , CA (US ) A61K 9 / 24 ( 2006 .01 ) ( 52 ) U . S . CI. ( 21 ) Appl. No. : 16 /289 ,499 CPC . .. .. A61K 9 /2031 (2013 . 01 ) ; A61K 9 /0065 ( 22 ) Filed : Feb . 28 , 2019 (2013 .01 ) ; A61K 9 / 209 ( 2013 .01 ) ; A61K 9 /2027 ( 2013 .01 ) ; A61K 31/ 192 ( 2013. 01 ) ; Related U . S . Application Data A61K 9 /2072 ( 2013 .01 ) (63 ) Continuation of application No. 16 /028 ,305 , filed on Jul. 5 , 2018 , now Pat . No . 10 , 258 ,575 , which is a (57 ) ABSTRACT continuation of application No . 15 / 173 ,596 , filed on The present disclosure provides a stable solid pharmaceuti Jun . 3 , 2016 . cal dosage form for oral administration . The dosage form (60 ) Provisional application No . 62 /313 ,092 , filed on Mar. includes a substrate that forms at least one compartment and 24 , 2016 , provisional application No . 62 / 296 , 087 , a drug content loaded into the compartment. The dosage filed on Feb . 17 , 2016 , provisional application No . form is so designed that the active pharmaceutical ingredient 62 / 170, 645 , filed on Jun . 3 , 2015 . of the drug content is released in a controlled manner. Patent Application Publication Jun . 27 , 2019 Sheet 1 of 20 US 2019 /0192440 A1 FIG . -

Table of Contents

Table of contents PRISMA checklist .............................................................................................................................................. 2 Tables Supplementary Table S1. Search strategy ..................................................................................................... 4 Supplementary Table S2. Characteristics of included randomized trials, stratified by patient type . 6 Supplementary Table S3. Ongoing trials ..................................................................................................... 10 Supplementary Table S4. Risk of bias assessment ................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. Supplementary Table S5. Sensitivity analysis: best-worse and worst-best case scenario’s ................ 11 Supplementary Table S6. Sensitivity analysis: trials with publication year ≥ 2005 ............................. 16 Supplementary Table S7. Sensitivity analysis: including LMWH types not a priori defined ..... Error! Bookmark not defined. Supplementary Table S8. Subgroup analysis: co-primary outcomes ..................................................... 16 Supplementary Table S9. Sensitivity analysis: proportion of SAE and cumulative SAE ................... 13 Figures Supplementary Figure S1. Forest plot of SAE, stratified for patient type ............................................. 17 Supplementary Figure S2. Forest plot of non-major bleeding, stratified for patient type .................. 18 Supplementary Figure S3. Forest plot of any VTE, stratified -

SYNOPSIS Name of Sponsor/Company: Individual Study

Clivarine. Protocol No. CL052 SYNOPSIS Name of Sponsor/Company: Individual study table referring (For national autllOrity use to part IV of the dossier only) Knoll GmbH Name of finished product: Volume: Clivarine Name of active ingredient(s): Tab/page: Reviparin sodium Title of study: A randomised controlIed trial comparing low molecular weight heparin (reviparin sodium) to standard of practice unfractionated heparin plus a vitamin K antagonist for the treatment of venous thromboembolism in a pediatric patient population Investigator name and address: Principal Investigators: Dr Maureen Andrew, Hamilton Civic Hospitals Research Centre, 711 Concession Street, Hamilton, Ontario L8V lC3, Canada; Dr Patti Massicotte, The Hospital for Sick Children, Division ofHematology/Oncology, 555 University Avenue, Toronto, Ontario M5G lX8, Canada Publication(s) (reference): None. Studied period (years): date of first enrolment: 29-Nov-97 I Phase of date last patient completed: 27-Jul-OO development: III Objectives: To compare the efficacy and safety of Clivarine (reviparin sodium) to unfractionatedheparin (UFH) plus vitamin K antagonist therapy for the treatment of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in a pediatric population. Methodology: Multicentre, randomised, controlled, parallel group, open trial with blinded outcome assessment to compare the efficacy and safety of Clivarine to UFH plus a vitamin K antagonist for the treatment of venous thromboembolism in children. Patients received either Clivarine or UFH plus a vitamin K antagonist for three months. Assessments were made at baseline, during the treatment period and at six months post-randomisation (follow-up). Number of patients: 352 patients were planned (176 in each treatment group) but the (planned and analysed) study was tenninated prematurely due to slow recruitment. -

Using Existing Data for Epidemiologic Research of Cardiovascular Diseases

Using existing data for epidemiologic research of cardiovascular diseases By Yongzhe Hong A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Medicine University of Alberta © Yongzhe Hong, 2018 Abstract Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are the leading cause of morbidity and mortality and have placed a significant burden on our society both regionally and globally. With the development of information technology, we are accumulating digitalized data at an exponential speed. This growing volume of existing data has provided researchers tremendous opportunities and resources to generate real-world evidence for healthcare decision making. Leveraging data from overwhelming numbers of available databases could effectively speed up the progress of scientific advances and provide a significant impact on clinical practice and public health. Despite that plenty of resources and efforts have been put to address health-related questions, countless unanswered questions remain and new hypotheses keep arising with the advance in healthcare system. Many of them can be addressed by epidemiologic studies using the available data without the primary data collection. Meanwhile, the challenges CVD researchers are facing when conducting research using existing data are less frequently discussed. In the thesis, I aim to address several clinical epidemiologic research questions and controversies in the field of cardiovascular diseases using available data, and discuss the challenges during the research process from a data user’s perspective to raise the awareness and to stimulate discussions. Chapter 2 is a diagnostic and community-wide study that evaluated the feasibility of using administrative health data to identify peripheral arterial disease (PAD) patients. -

Update on Low Molecular Weight Heparins at the Beginning of Third Millennium

European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences 2011; 15: 950-959 Update on low molecular weight heparins at the beginning of third millennium. Focus on reviparin R. DEL BONO, G. MARTINI, R. VOLPI Haemostasis and Thrombosis Centre, University-Hospital Institute of “Spedali Civili di Brescia”, Brescia (Italy) Abstract. – Background: This review pro- Outline of Low Molecular Weight vides an outline of the main pharmacological Heparin Pharmacology and clinical features of low molecular weight he- parins (LMWHs) and a wider description of re- Low molecular weight heparins (LMWHs), viparin. The basic pharmacological properties of marketed first in Europe from the second half of LMWHs are compared with those of unfraction- ated heparin, showing clear advantages of the ’80, represented a new therapeutic measure, not former, mainly as for pharmacokinetic profile. only alternative and more practical, but also often Design: Consequently LMWHs are character- more effective than standard heparin in many ized by a more predictable behaviour. A key is- clinical fields1-3. sue is the lack of “bioequivalence”: LMWHs are As known, the search on LMWHs (obtained in fact distinct chemical entities, with typical by unfractionated heparin (UFH) through differ- pharmacological and clinical profile for each agent. Therefore, they are not reciprocally inter- ent chemical or enzymatic methods) has been changeable. The efficacy and safety of re- prompted by some basic observations: viparin, a second generation LMWH, has been – markedly lower activity of LMWHs on factor evaluated in many clinical trials as both throm- IIa than on factor Xa of the coagulation cas- bosis prevention and treatment. Reviparin use cade4,5; is documented in general and orthopaedic – higher risk/benefit ratio of LMWHs versus surgery. -

PDF Download

Review Article 201 How Do I Reverse Oral and Parenteral Anticoagulants? Wie Reversiere ich die Wirkung von Oralen und Parenteralen Antikoagulanzien? Jürgen Koscielny1 Edita Rutkauskaite1 Christoph Sucker2 Christian von Heymann3 1 Charité, Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Gerinnungsambulanz mit Address for correspondence Jürgen Koscielny, Charité, Hämophiliezentrum im Ambulanten, Gesundheitszentrum (AGZ), Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Gerinnungsambulanz mit Berlin, Germany HämophiliezentrumimAmbulantenGesundheitszentrum(AGZ), 2 Gerinnungszentrum Berlin Dr. Sucker, Berlin, Germany Berlin, Germany (e-mail: [email protected]). 3 Klinik für Anästhesie, Intensivmedizin, Notfallmedizin und Schmerztherapie, Vivantes Klinikum, Im Friedrichshain, Berlin, Germany Hämostaseologie 2020;40:201–213. Abstract An understanding of reversal strategies alone is important to safely and effectively care for patients in cases of bleeding or invasive procedures. The recent diversification in the number of licensed anticoagulants makes an understanding of drug-specific reversal strategies essential. Intravenous or oral vitamin K can reverse the effect of vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) within 12 to 48 hours and is indicated for any bleeding or an international normalized ratio >10 or 4.5 to 10 in patients with additional risk factors for bleeding. Furthermore, an additional administration of prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC) may be necessary in cases of major bleeding related to VKA. Protamine (chloride or sulfate) fully reverses the effect of unfractionated heparin and partially in low-molecular-weight heparin. Idarucizumab has been approved for dabigatran reversal, whereas andexanet alfa is approved for the reversal of some oral factor Xa inhibitors (apixaban, rivaroxaban). PCC seems to enhance the haemo- static potential for the reversal of the effect of FXa-inhibitors. So far, there are promising but only limited data on the efficacy of this approach available. -

Low Molecular Weight Heparins and Their Clinical Applications

CHAPTER TWO Low molecular weight heparins and their clinical applications Cui Haoa,*, Mojian Sunb, Hongmei Wangc, Lijuan Zhanga, Wei Wangd aSystems Biology and Medicine Center for Complex Diseases, Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University, Qingdao, China bDepartment of Medical Records, Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University, Qingdao, China cRespiratory Department, Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University, Qingdao, China dKey Laboratory of Marine Drugs, Ministry of Education, Shandong Provincial Key Laboratory of Glycoscience & Glycoengineering, Ocean University of China, Qingdao, China *Corresponding author: e-mail address: [email protected] Contents 1. Introduction 22 2. Structure of LMWHs 23 3. Clinical uses of LMWHs 25 4. Update on the LMWHs under clinic trials and its potential applications 27 4.1 Anti-tumor 27 4.2 Anti-viral 30 4.3 Anti-inflammation 30 4.4 Anti-diabetes-associated complications 31 4.5 Other applications 32 5. Concluding remarks 32 Acknowledgments 33 References 34 Abstract Heparin is an anticoagulant medication that was discovered in 1917 and used in clinic since 1935. Low molecular weight heparins (LMWHs) represent a refined use of heparin as anticoagulant medications that were developed in 1980s. LMWHs are obtained by cleaving heparin with different chemical or enzymatic methods. Eight chemically distinct and officially approved LMWHs are Bemiparin, Certoparin, Dalteparin, Enoxaparin, Nadroparin, Parnaparin, Reviparin, and Tinzaparin. LMWHs are mainly used for preventing blood clots, for treating deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, and for treating myocardial infarction. LMWHs have advantages over heparin in that they can be used at home with good predictability, dose-dependent plasma levels, a long half-life, less bleeding for a given antithrombotic even, smaller risk of osteoporosis in long-term use, and smaller risk of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and thrombo- sis, a potential side effect of heparin. -

Reviparin Sodium May Be Reduced by the Reserpine

1388 Cardiovascular Drugs It is probably not necessary to stop reserpine during anaesthesia, Description. Reteplase is a nonglycosylated protein produced 3150 and 5150 with a characteristic value of about 4150. The de- although the effects of CNS depressants may be enhanced by re- by recombinant DNA technology. It consists of selected domains gree of sulfation is about 2.1 per disaccharide unit. serpine. of human tissue plasminogen activator. Units Incompatibility. Reteplase may precipitate out of solution if it As for Low-molecular-weight Heparins, p.1329. Interactions 1 Patients taking reserpine may be hypersensitive to adrenaline is given with heparin in the same intravenous line. Reteplase and heparin must therefore be given separately; if a single intra- Adverse Effects, Treatment, and Precautions and other direct-acting sympathomimetics, which should not be As for Low-molecular-weight Heparins, p.1329. given except to antagonise reserpine. The effects of indirect-act- venous line is used it must be flushed thoroughly with sodium ing sympathomimetics such as ephedrine may be decreased by chloride 0.9% or with glucose 5% before, and after, reteplase in- Severe bleeding with reviparin sodium may be reduced by the reserpine. The hypotensive effects of reserpine are enhanced by jection. slow intravenous injection of protamine sulfate; about 1.2 mg of thiazide diuretics and other antihypertensives. Reserpine may 1. Committee on Safety of Medicines/Medicines Control Agency. protamine sulfate is stated to inhibit the effect of 100 units of re- cause excitation and hypertension in patients receiving MAOIs. Reteplase (Rapilysin): incompatibility with heparin. Current viparin sodium. Problems 2000; 26: 5.