Deadjectival Human Nouns: Conversion, Nominal Ellipsis, Or Mixed Category?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rethinking Social Action. Core Values in Practice | RSACVP 2017 | 6-9 April 2017 | Suceava – Romania Rethinking Social Action

Available online at: http://lumenpublishing.com/proceedings/published-volumes/lumen- proceedings/rsacvp2017/ 8th LUMEN International Scientific Conference Rethinking Social Action. Core Values in Practice | RSACVP 2017 | 6-9 April 2017 | Suceava – Romania Rethinking Social Action. Core Values in Practice The Convertor Status of Article of Case and Number in the Romanian Language Diana-Maria ROMAN* https://doi.org/10.18662/lumproc.rsacvp2017.62 How to cite: Roman, D.-M. (2017). The Convertor Status of Article of Case and Number in the Romanian Language. In C. Ignatescu, A. Sandu, & T. Ciulei (eds.), Rethinking Social Action. Core Values in Practice (pp.682-694). Suceava, Romania: LUMEN Proceedings https://doi.org/10.18662/lumproc.rsacvp2017.62 © The Authors, LUMEN Conference Center & LUMEN Proceedings. Selection and peer-review under responsibility of the Organizing Committee of the conference 8th LUMEN International Scientific Conference Rethinking Social Action. Core Values in Practice | RSACVP 2017 | 6-9 April 2017 | Suceava – Romania The Convertor Status of Article of Case and Number in the Romanian Language Diana-Maria ROMAN1* Abstract This study is the outcome of research on the grammar of the contemporary Romanian language. It proposes a discussion of the marked nominalization of adjectives in Romanian, the analysis being focused on the hypostases of the convertor (nominalizer). Within this area of research, contemporary scholarly treaties have so far accepted solely nominalizers of the determinative article type (definite and indefinite) and nominalizers of the vocative desinence type, in the singular. However, with regard to the marked conversion of an adjective to the large class of nouns, the phenomenon of enclitic articulation does not always also entail the individualization of the nominalized adjective, as an expression of the category of definite determination. -

Pronouns, Logical Variables, and Logophoricity in Abe Author(S): Hilda Koopman and Dominique Sportiche Source: Linguistic Inquiry, Vol

MIT Press Pronouns, Logical Variables, and Logophoricity in Abe Author(s): Hilda Koopman and Dominique Sportiche Source: Linguistic Inquiry, Vol. 20, No. 4 (Autumn, 1989), pp. 555-588 Published by: MIT Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4178645 Accessed: 22-10-2015 18:32 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Linguistic Inquiry. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.97.27.20 on Thu, 22 Oct 2015 18:32:27 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Hilda Koopman Pronouns, Logical Variables, Dominique Sportiche and Logophoricity in Abe 1. Introduction 1.1. Preliminaries In this article we describe and analyze the propertiesof the pronominalsystem of Abe, a Kwa language spoken in the Ivory Coast, which we view as part of the study of pronominalentities (that is, of possible pronominaltypes) and of pronominalsystems (that is, of the cooccurrence restrictionson pronominaltypes in a particulargrammar). Abe has two series of thirdperson pronouns. One type of pronoun(0-pronoun) has basically the same propertiesas pronouns in languageslike English. The other type of pronoun(n-pronoun) very roughly corresponds to what has been called the referential use of pronounsin English(see Evans (1980)).It is also used as what is called a logophoric pronoun-that is, a particularpronoun that occurs in special embedded contexts (the logophoric contexts) to indicate reference to "the person whose speech, thought or perceptions are reported" (Clements (1975)). -

Toward a Shared Syntax for Shifted Indexicals and Logophoric Pronouns

Toward a Shared Syntax for Shifted Indexicals and Logophoric Pronouns Mark Baker Rutgers University April 2018 Abstract: I argue that indexical shift is more like logophoricity and complementizer agreement than most previous semantic accounts would have it. In particular, there is evidence of a syntactic requirement at work, such that the antecedent of a shifted “I” must be a superordinate subject, just as the antecedent of a logophoric pronoun or the goal of complementizer agreement must be. I take this to be evidence that the antecedent enters into a syntactic control relationship with a null operator in all three constructions. Comparative data comes from Magahi and Sakha (for indexical shift), Yoruba (for logophoric pronouns), and Lubukusu (for complementizer agreement). 1. Introduction Having had an office next to Lisa Travis’s for 12 formative years, I learned many things from her that still influence my thinking. One is her example of taking semantic notions, such as aspect and event roles, and finding ways to implement them in syntactic structure, so as to advance the study of less familiar languages and topics.1 In that spirit, I offer here some thoughts about how logophoricity and indexical shift, topics often discussed from a more or less semantic point of view, might have syntactic underpinnings—and indeed, the same syntactic underpinnings. On an impressionistic level, it would not seem too surprising for logophoricity and indexical shift to have a common syntactic infrastructure. Canonical logophoricity as it is found in various West African languages involves using a special pronoun inside the finite CP complement of a verb to refer to the subject of that verb. -

Possessive Agreement Turned Into a Derivational Suffix Katalin É. Kiss 1

Possessive agreement turned into a derivational suffix Katalin É. Kiss 1. Introduction The prototypical case of grammaticalization is a process in the course of which a lexical word loses its descriptive content and becomes a grammatical marker. This paper discusses a more complex type of grammaticalization, in the course of which an agreement suffix marking the presence of a phonologically null pronominal possessor is reanalyzed as a derivational suffix marking specificity, whereby the pro cross-referenced by it is lost. The phenomenon in question is known from various Uralic languages, where possessive agreement appears to have assumed a determiner-like function. It has recently been a much discussed question how the possessive and non-possessive uses of the agreement suffixes relate to each other (Nikolaeva 2003); whether Uralic definiteness-marking possessive agreement has been grammaticalized into a definite determiner (Gerland 2014), or it has preserved its original possessive function, merely the possessor–possessum relation is looser in Uralic than in the Indo-Europen languages, encompassing all kinds of associative relations (Fraurud 2001). The hypothesis has also been raised that in the Uralic languages, possessive agreement plays a role in organizing discourse, i.e., in linking participants into a topic chain (Janda 2015). This paper helps to clarify these issues by reconstructing the grammaticalization of possessive agreement into a partitivity marker in Hungarian, the language with the longest documented history in the Uralic family. Hungarian has two possessive morphemes functioning as a partitivity marker: -ik, an obsolete allomorph of the 3rd person plural possessive suffix, and -(j)A, the productive 3rd person singular possessive suffix. -

Assibilation Or Analogy?: Reconsideration of Korean Noun Stem-Endings*

Assibilation or analogy?: Reconsideration of Korean noun stem-endings* Ponghyung Lee (Daejeon University) This paper discusses two approaches to the nominal stem-endings in Korean inflection including loanwords: one is the assibilation approach, represented by H. Kim (2001) and the other is the analogy approach, represented by Albright (2002 et sequel) and Y. Kang (2003b). I contend that the assibilation approach is deficient in handling its underapplication to the non-nominal categories such as verb. More specifically, the assibilation approach is unable to clearly explain why spirantization (s-assibilation) applies neither to derivative nouns nor to non-nominal items in its entirety. By contrast, the analogy approach is able to overcome difficulties involved with the assibilation position. What is crucial to the analogy approach is that the nominal bases end with t rather than s. Evidence of t-ending bases is garnered from the base selection criteria, disparities between t-ending and s-ending inputs in loanwords. Unconventionally, I dare to contend that normative rules via orthography intervene as part of paradigm extension, alongside semantic conditioning and token/type frequency. Keywords: inflection, assibilation, analogy, base, affrication, spirantization, paradigm extension, orthography, token/type frequency 1. Introduction When it comes to Korean nominal inflection, two observations have captivated our attention. First, multiple-paradigms arise, as explored in previous literature (K. Ko 1989, Kenstowicz 1996, Y. Kang 2003b, Albright 2008 and many others).1 (1) Multiple-paradigms of /pʰatʰ/ ‘red bean’ unmarked nom2 acc dat/loc a. pʰat pʰaʧʰ-i pʰatʰ-ɨl pʰatʰ-e b. pʰat pʰaʧʰ-i pʰaʧʰ-ɨl pʰatʰ-e c. -

Nominal Internal and External Topic and Focus: Evidence from Mandarin

University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics Volume 20 Issue 1 Proceedings of the 37th Annual Penn Article 17 Linguistics Conference 2014 Nominal Internal and External Topic and Focus: Evidence from Mandarin Yu-Yin Hsu Bard College Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl Recommended Citation Hsu, Yu-Yin (2014) "Nominal Internal and External Topic and Focus: Evidence from Mandarin," University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics: Vol. 20 : Iss. 1 , Article 17. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol20/iss1/17 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol20/iss1/17 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nominal Internal and External Topic and Focus: Evidence from Mandarin Abstract Taking the Cartographic Approach, I argue that the left periphery of nominals in Mandarin (i.e., the domain before demonstrative) has properties similar to the split-CP domain proposed by Rizzi (1997). In addition, I argue that the nominal internal domain (i.e., under demonstrative but outside of NP) encodes information structure in a way similar to the sentence-internal Topic and Focus that has been put forth in the literature. In this paper, I show that identifying Topic and Focus within a nominal at such two distinct domains helps to explain various so-called “reordering” and extraction phenomena affecting nominal elements, their interpretation, and their associated discourse functions. The result of this paper supports the parallelisms between noun phrases and clauses and it provides a new perspective to evaluate such theoretical implication, that is, the interaction between syntax and information structure. -

A THEORY of NOMINAL CONCORD a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requirements for the Degree Of

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ A THEORY OF NOMINAL CONCORD A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in LINGUISTICS by Mark Norris June 2014 The Dissertation of Mark Norris is approved: Professor Jorge Hankamer, Chair Professor Sandra Chung Professor James McCloskey Dean Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Mark Norris 2014 Table of Contents List of Figures vi List of Tables vii Abstract viii Dedication x Acknowledgments xi 1 Introduction 3 1.1 Themainpuzzle.................................. 3 1.2 EmpiricalBackground ... ...... ..... ...... ...... ... 5 1.2.1 Grammaticalsketch ........................... 6 1.2.2 Nominalmorphology........................... 8 1.2.3 Nominal morphophonology . 12 1.2.4 Datasources ............................... 14 1.2.5 ThecaseforEstonian...... ..... ...... ...... .... 16 1.3 Theoretical Background . 16 1.3.1 Some important syntactic assumptions . ..... 17 1.3.2 Some important morphological assumptions . ...... 20 1.4 Organization.................................... 21 2 Estonian Nominal Morphosyntax 23 2.1 Introduction.................................... 23 2.2 TheDPlayerinEstonian .. ...... ..... ...... ...... ... 25 2.2.1 Estonian does not exhibit properties of articleless languages . 28 2.2.2 Overt material in D0 inEstonian..................... 44 2.2.3 Evidence for D0 from demonstratives . 50 2.2.4 Implications for the Small Nominal Hypothesis . ....... 54 2.3 Cardinal numerals in Estonian . 60 2.3.1 The numeral’s “complement” . 60 2.3.2 Previous analyses of numeral-noun constructions . ......... 64 iii 2.4 Two structures for NNCs in Estonian . ..... 75 2.4.1 The size of the NP+ ............................ 76 2.4.2 The higher number feature in Estonian . 79 2.4.3 Higher adjectives and possessors . 81 2.4.4 Plural numerals in Estonian are specifiers . -

Where Do New Words Like Boobage, Flamage, Ownage Come From? Tracking the History of ‑Age Words from 1100 to 2000 in the OED3

Lexis Journal in English Lexicology 12 | 2018 Lexical and Semantic Neology in English Where do new words like boobage, flamage, ownage come from? Tracking the history of ‑age words from 1100 to 2000 in the OED3 Chris A. Smith Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/lexis/2167 DOI: 10.4000/lexis.2167 ISSN: 1951-6215 Publisher Université Jean Moulin - Lyon 3 Electronic reference Chris A. Smith, « Where do new words like boobage, flamage, ownage come from? Tracking the history of ‑age words from 1100 to 2000 in the OED3 », Lexis [Online], 12 | 2018, Online since 14 December 2018, connection on 03 May 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/lexis/2167 ; DOI : 10.4000/ lexis.2167 This text was automatically generated on 3 May 2019. Lexis is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Where do new words like boobage, flamage, ownage come from? Tracking the hist... 1 Where do new words like boobage, flamage, ownage come from? Tracking the history of ‑age words from 1100 to 2000 in the OED3 Chris A. Smith Introduction 1 This study aims to trace the evolution of nominal ‑age formation in the OED3, from its origins as a product of borrowing from Latin or French from 1100, to its status as an innovative internal derivation process. The suffix ‑age continues today to coin newly- or non-lexicalized forms such as ownage, boobage, brushage, suggestive of the continued productivity of a long-standing century-old suffix. This remarkable success appears to distinguish ‑age from similar Latinate suffixes such as ‑ment and ‑ity (see Gadde [1910]) and raises the question of the reasons behind this adaptability. -

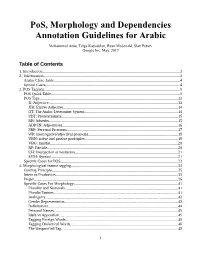

Pos, Morphology and Dependencies Annotation Guidelines for Arabic

PoS, Morphology and Dependencies Annotation Guidelines for Arabic Mohammed Attia, Tolga Kayadelen, Ryan Mcdonald, Slav Petrov Google Inc. May, 2017 Table of Contents 1. Introduction............................................................................................................................................2 2. Tokenization...........................................................................................................................................3 Arabic Clitic Table................................................................................................................................4 Special Cases.........................................................................................................................................4 3. POS Tagging..........................................................................................................................................8 POS Quick Table...................................................................................................................................8 POS Tags.............................................................................................................................................13 JJ: Adjective....................................................................................................................................13 JJR: Elative Adjective.....................................................................................................................14 DT: The Arabic Determiner System...............................................................................................14 -

Ikizu-Sizaki Orthography Orthography Statement

IKIZUIKIZU----SIZAKISIZAKI ORTHOGRAPHY STATEMENT SIL International UgandaUganda----TanzaniaTanzania Branch IkizuIkizu----SizakiSizaki Orthography Statement Approved Orthography Edition Acknowledgements Many individuals contributed to this document by formatting the structure, contributing the language data, organizing the data, writing the document and by giving advice for editing the document. This document was authored by Holly Robinson, and it is an updated and expanded version of the Ikizu Orthography Sketch, which was authored by Michelle Smith and Hazel Gray. Additional contributors from SIL International include: Oliver Stegen, Helen Eaton, Leila Schroeder, Oliver Rundell, Tim Roth, Dusty Hill, and Mike Diercks. Contributors from the Ikizu language community include: Rukia Rahel Manyori and Ismael Waryoba (Ikizu Bible translators), as well as Kitaboka Philipo, Bahati M. Seleman, Joseph M. Edward, Magwa P. Marara, Mwassi Mong’ateko, Ibrahimu Ketera, Amosi Mkono, Dennis Paul, Nickson Obimbo, Muhuri Keng’are, Matutu Ngese. © SIL International UgandaUganda----TanzaniaTanzania Branch P.O Box 44456 00100 Nairobi, Kenya P.O. Box 60368 Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania P.O. Box 7444 Kampala, Uganda Approved Orthography Edition: April 2016 2 Contents 1.1.1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................................... ......... 555 1.1 Classification .................................................................................................. -

5 Adjectives and Adverbs

5 ADJECTIVES AND ADVERBS 1 Choose the correct alternative in the sentences below. If you find both alternatives acceptable, explain any difference in meaning. a. All the venues are easy/easily accessible. b. There’s a possible/possibly financial problem. c. We admired the wonderful/wonderfully panorama. d. Our neighbours are (simple)/simply people who live near us. Although less likely in this case, the adjective “simple” could be used as a premodifier to describe the noun (that is, the neighbours are not sophisticated people). Since the sentence seems to be a more general description of neighbours, however, the adverb “simply” is the more likely choice. The adverb serves as a comment on the part of the speaker. e. They seemed happy/happily about George’s victory. f. Similar/Similarly teams of medical advisers were called upon. g. Something in here smells horrible/horribly. Normally an adjective will follow a linking verb to describe a quality of the subject ref- erent. However, the adverb “horribly” can be used to refer to the intensity of the smell. h. This cream will give you a beautiful/beautifully smooth complexion. i. Particular/Particularly groups such as recent immigrants felt their needs were being overlooked. INTRODUCING ENGLISH GRAMMAR, THIRD EDITION KEY TO EXERCISES 5 Adjectives and Adverbs The adjective “particular” premodifies or describes the noun “groups”, whereas the use of the adverb “particularly” functions as a comment on the part of the speaker. 2 Explain the difference in form and meaning between the members of each pair. a. 1 She is a natural blonde. -

Philosophy of Language in the Twentieth Century Jason Stanley Rutgers University

Philosophy of Language in the Twentieth Century Jason Stanley Rutgers University In the Twentieth Century, Logic and Philosophy of Language are two of the few areas of philosophy in which philosophers made indisputable progress. For example, even now many of the foremost living ethicists present their theories as somewhat more explicit versions of the ideas of Kant, Mill, or Aristotle. In contrast, it would be patently absurd for a contemporary philosopher of language or logician to think of herself as working in the shadow of any figure who died before the Twentieth Century began. Advances in these disciplines make even the most unaccomplished of its practitioners vastly more sophisticated than Kant. There were previous periods in which the problems of language and logic were studied extensively (e.g. the medieval period). But from the perspective of the progress made in the last 120 years, previous work is at most a source of interesting data or occasional insight. All systematic theorizing about content that meets contemporary standards of rigor has been done subsequently. The advances Philosophy of Language has made in the Twentieth Century are of course the result of the remarkable progress made in logic. Few other philosophical disciplines gained as much from the developments in logic as the Philosophy of Language. In the course of presenting the first formal system in the Begriffsscrift , Gottlob Frege developed a formal language. Subsequently, logicians provided rigorous semantics for formal languages, in order to define truth in a model, and thereby characterize logical consequence. Such rigor was required in order to enable logicians to carry out semantic proofs about formal systems in a formal system, thereby providing semantics with the same benefits as increased formalization had provided for other branches of mathematics.