Herbert Marcuse Douglas Kellner ( Herbert Marcuse Gained World Renown During the 1960

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CRITICAL THEORY and AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism

CDSMS EDITED BY JEREMIAH MORELOCK CRITICAL THEORY AND AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism edited by Jeremiah Morelock Critical, Digital and Social Media Studies Series Editor: Christian Fuchs The peer-reviewed book series edited by Christian Fuchs publishes books that critically study the role of the internet and digital and social media in society. Titles analyse how power structures, digital capitalism, ideology and social struggles shape and are shaped by digital and social media. They use and develop critical theory discussing the political relevance and implications of studied topics. The series is a theoretical forum for in- ternet and social media research for books using methods and theories that challenge digital positivism; it also seeks to explore digital media ethics grounded in critical social theories and philosophy. Editorial Board Thomas Allmer, Mark Andrejevic, Miriyam Aouragh, Charles Brown, Eran Fisher, Peter Goodwin, Jonathan Hardy, Kylie Jarrett, Anastasia Kavada, Maria Michalis, Stefania Milan, Vincent Mosco, Jack Qiu, Jernej Amon Prodnik, Marisol Sandoval, Se- bastian Sevignani, Pieter Verdegem Published Critical Theory of Communication: New Readings of Lukács, Adorno, Marcuse, Honneth and Habermas in the Age of the Internet Christian Fuchs https://doi.org/10.16997/book1 Knowledge in the Age of Digital Capitalism: An Introduction to Cognitive Materialism Mariano Zukerfeld https://doi.org/10.16997/book3 Politicizing Digital Space: Theory, the Internet, and Renewing Democracy Trevor Garrison Smith https://doi.org/10.16997/book5 Capital, State, Empire: The New American Way of Digital Warfare Scott Timcke https://doi.org/10.16997/book6 The Spectacle 2.0: Reading Debord in the Context of Digital Capitalism Edited by Marco Briziarelli and Emiliana Armano https://doi.org/10.16997/book11 The Big Data Agenda: Data Ethics and Critical Data Studies Annika Richterich https://doi.org/10.16997/book14 Social Capital Online: Alienation and Accumulation Kane X. -

1 Douglas Kellner [

Douglas Kellner [http://www.gseis.ucla.edu/faculty/kellner/] T.W. Adorno and the Dialectics of Mass Culture While T.W. Adorno is a lively figure on the contemporary cultural scene, his thought in many ways cuts across the grain of emerging postmodern orthodoxies. Although Adorno anticipated many post-structuralist critiques of the subject, philosophy, and intellectual practice, his work clashes with the postmodern celebration of media culture, attacks on modernism as obsolete and elitist, and the more affirmative attitude toward contemporary culture and society found in many, but not all, postmodern circles. Adorno is thus a highly contradictory figure in the present constellation, anticipating some advanced tendencies of contemporary thought, while standing firming against other regnant intellectual attitudes and positions. In this article, I argue that Adorno's analyses of the functions of mass culture and communications in contemporary societies constitute valuable, albeit controversial, legacies. Adorno excelled both as a critic of so-called "high culture" and "mass culture," while producing many important texts in these areas. His work is distinguished by the close connection between social theory and cultural critique, and by his ability to contextualize culture within social developments, while providing sharp critical analysis. Accordingly, I discuss Adorno's analysis of the dialectics of mass culture, focusing on his critique of popular music, the culture industry, and consumer culture. I argue that Adorno's critique of mass culture is best read and understood in the context of his work with information superhighway. In conclusion, I offer alternative perspectives on mass communication and culture, and some criticisms of Adorno's position. -

Qualitative Freedom

Claus Dierksmeier Qualitative Freedom - Autonomy in Cosmopolitan Responsibility Translated by Richard Fincham Qualitative Freedom - Autonomy in Cosmopolitan Responsibility Claus Dierksmeier Qualitative Freedom - Autonomy in Cosmopolitan Responsibility Claus Dierksmeier Institute of Political Science University of Tübingen Tübingen, Baden-Württemberg, Germany Translated by Richard Fincham American University in Cairo New Cairo, Egypt Published in German by Published by Transcript Qualitative Freiheit – Selbstbestimmung in weltbürgerlicher Verantwortung, 2016. ISBN 978-3-030-04722-1 ISBN 978-3-030-04723-8 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-04723-8 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018964905 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2019. This book is an open access publication. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this book are included in the book’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the book’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. -

Heideggerian Marxism

1 2 3 4 5 Heideggerian Marxism 6 7 8 9 10 11 [First Page] 12 [-1], (1) 13 14 15 Lines: 0 to 16 ——— 17 * 429.1755pt 18 ——— 19 Normal Page 20 * PgEnds: PageB 21 22 [-1], (1) 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 1 european horizons 2 Series Editors 3 Richard Golsan, 4 Texas A&M University 5 6 Christopher Flood, 7 University of Surrey 8 Jeffrey T. Schnapp, 9 Stanford University 10 11 Richard Wolin, 12 The Graduate Center, [-2], (2) 13 City University of New York 14 15 Lines: 15 16 ——— 17 * 321.29399pt 18 ——— 19 Normal P 20 * PgEnds: 21 22 [-2], (2) 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 1 2 3 4 5 Heideggerian 6 7 8 9 Marxism 10 11 12 [-3], (3) 13 14 15 Lines: 36 to 16 ——— 17 0.78pt PgV 18 Herbert Marcuse ——— 19 Normal Page 20 * PgEnds: PageB 21 22 [-3], (3) 23 24 25 Edited by 26 27 Richard Wolin and John Abromeit 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 university of nebraska press 37 lincoln and london 1 © 2005 by the University of Nebraska Press 2 All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America 3 ⅜ϱ 4 The essays of Herbert Marcuse contained in this volume 5 are reprinted with the permission of the Literary Estate of Herbert Marcuse Peter Marcuse, executor. 6 Supplementary material from previously unpublished work of Herbert Marcuse, 7 much now in the archives of the Johann Wolfgang Goethe University 8 Frankfurt am Main, is being published by Routledge in a six-volume series edited by Douglas Kellner. -

Critical Theory of Herbert Marcuse: an Inquiry Into the Possibility of Human Happiness

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1986 Critical theory of Herbert Marcuse: An inquiry into the possibility of human happiness Michael W. Dahlem The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Dahlem, Michael W., "Critical theory of Herbert Marcuse: An inquiry into the possibility of human happiness" (1986). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5620. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5620 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COPYRIGHT ACT OF 1976 This is an unpublished manuscript in which copyright sub s is t s, Any further reprinting of its contents must be approved BY THE AUTHOR, Mansfield Library U n iv e rs ity o f Montana Date :_____1. 9 g jS.__ THE CRITICAL THEORY OF HERBERT MARCUSE: AN INQUIRY INTO THE POSSIBILITY OF HUMAN HAPPINESS By Michael W. Dahlem B.A. Iowa State University, 1975 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Montana 1986 Approved by Chairman, Board of Examiners Date UMI Number: EP41084 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

CRITICAL THEORY Past, Present, Future Anders Bartonek and Sven-Olov Wallensein (Eds.) SÖDERTÖRN PHILOSOPHICAL STUDIES

CRITICAL THEORY Past, Present, Future Anders Bartonek and Sven-Olov Wallensein (eds.) SÖDERTÖRN PHILOSOPHICAL STUDIES The series is attached to Philosophy at Sder- trn University. Published in the series are es- says as well as anthologies, with a particular em- phasis on the continental tradition, understood in its broadest sense, from German idealism to phenomenology, hermeneutics, critical theory and contemporary French philosophy. The com- mission of the series is to provide a platform for the promotion of timely and innovative phil- osophical research. Contributions to the series are published in English or Swedish. Cover image: Kristofer Nilson, System (Portrait of a Swedish Tax Form), 2020, Lead pencil drawing on chalk paint, on mdf 59.2 x 42 cm. Photo: Jesper Petersen. Te Swedish tax form is one of many systems designed to handle and present information. Mapped onto the surface of an artwork, it opens a free space; an untouched surface where everything can exist at the same time. Kristofer Nilson Critical Theory Past, Present, Future Edited by Anders Bartonek & Sven-Olov Wallenstein Sdertrns hgskola Sdertrns University Library SE-141 89 Huddinge www.sh.se/publications © the Authors Published under Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License Cover layout: Jonathan Robson Graphic form: Per Lindblom & Jonathan Robson Printed by Elanders, Stockholm 2021 Sdertrn Philosophical Studies 28 ISSN 1651-6834 Sdertrn Academic Studies 83 ISSN 1650-433X ISBN 978-91-89109-35-3 (print) ISBN 978-91-89109-36-0 (digital) Contents Introduction -

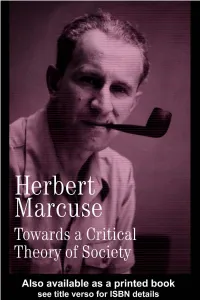

Towards a Critical Theory of Society Collected Papers of Herbert Marcuse Edited by Douglas Kellner

TOWARDS A CRITICAL THEORY OF SOCIETY COLLECTED PAPERS OF HERBERT MARCUSE EDITED BY DOUGLAS KELLNER Volume One TECHNOLOGY, WAR AND FASCISM Volume Two TOWARDS A CRITICAL THEORY OF SOCIETY Volume Three FOUNDATIONS OF THE NEW LEFT Volume Four ART AND LIBERATION Volume Five PHILOSOPHY, PSYCHOANALYSIS AND EMANCIPATION Volume Six MARXISM, REVOLUTION AND UTOPIA TOWARDS A CRITICAL THEORY OF SOCIETY HERBERT MARCUSE COLLECTED PAPERS OF HERBERT MARCUSE Volume Two Edited by Douglas Kellner London and New York First published 2001 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2003. © 2001 Peter Marcuse Selection and Editorial Matter © 2001 Douglas Kellner Afterword © Jürgen Habermas All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Marcuse, Herbert, 1898– Towards a critical theory of society / Herbert Marcuse; edited by Douglas Kellner. p. cm. – (Collected papers of Herbert Marcuse; v. 2) Includes bibliographical -

An Essay on Liberation by Herbert Marcuse

An Essay on Liberation by Herbert Marcuse 1969 Title: An Essay on Liberation Author: Marcuse, Herbert (1898 - 1979) Retrieved from: Facsimile version with OCR: http://libgen.org/search.php also in: http://www.lifeaftercapitalism.info/downloads/read/Philosophy/Herbert% 20Marcuse/Herbert%20Marcuse%20- %20An%20Essay%20on%20Liberation%20(Beacon,%201969).pdf https://wiki.brown.edu/confluence/download/attachments/73535007/an_ essay_on_liberation.pdf 2 3 Herbert Marcuse (July 19, 1898 – July 29, 1979) was a German Jewish philosopher, sociologist and political theorist, associated with the Frankfurt School of critical theory. Born in Berlin into a Jewish family, Marcuse studied at the universities of Berlin and Freiburg. He was a prominent figure in the Frankfurt-based Institute for Social Research - what later became known as the Frankfurt School. He was married to Sophie Wertheim (1924- 1951), Inge Neumann (1955-1972), and Erica Sherover (1976-1979). Active in the United States after 1934, his intellectual concerns were the dehumanizing effects of capitalism and modern technology. After his studies, in the late 1960s and the 1970s he became known as the preeminent theorist of the New Left and the student movements of Germany, France, and the USA. Between 1943 and 1950, Marcuse worked in US Government Service, which helped form the basis of his book Soviet Marxism (1964). Celebrated as the "Father of the New Left," his best known works are Eros and Civilization (1955) and One-Dimensional Man (1964). His Marxist scholarship inspired many radical intellectuals and political activists in the 1960s and '70s, both in the U.S. and internationally. Herbert Marcuse 4 Contents Acknowledgments 6 Preface 7 Introduction 9 1 - A Biological Foundation for Socialism? 12 2 - The New Sensibility 22 3 - Subverting Forces -- in Transition 38 4 - Solidarity 56 5 Acknowledgments Thanks Again to my friends who read the manuscript and whose comments and criticism I heeded throughout: especially Leo Lowenthal (University of California at Berkeley), Arno J. -

Theories of Political Action

1 THEORIES OF POLITICAL ACTION POLS 520, Spring 2013 Professor Bradley Macdonald Office: C366 Clark Office Hours: TW 2-3:30 or by appointment Telephone #: 491-6943 E-mail: [email protected] Preliminary Remarks: The character of political theory is intimately related to the diverse political practices in which the theorist wrote. Particularly in the contemporary period, theorists have increasingly recognized this political nature to their enterprise by clarifying the linkages of their theory to politics and by rethinking the way in which their ideas may promote social and political change. This critical reassessment has become particularly important in the wake of the dissolution of both classical liberalism and classical Marxism as political ideologies guaranteeing universal human emancipation, not to mention providing conceptual tools to understand the unique political dilemmas facing political actors in the 21st century. If there have been differing ideologies and theories that have confronted new conditions, there are also different strategies and tactics that have been increasingly revamped and rearticulated to engage our contemporaneity. If anything, the present century increasingly gives rise to issues associated with the nature of the “political.” How do we define political action and political knowledge? In what way is politics related to cultural practices (be they art, popular culture, or informational networks)? In what way is political action imbricated within economic practices? How has politics changed given the processes associated with globalization? This course will attempt to explore some of the more important developments within recent theory associated with defining differing positions on the nature of politics and the political. -

Why Rawlsian Liberalism Has Failed and How Proudhonian Anarchism Is the Solution

A Thesis entitled Why Rawlsian Liberalism has Failed and How Proudhonian Anarchism is the Solution by Robert Pook Submitted to the graduate faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in Philosophy __________________________________ Dr. Benjamin Pryor, Committee Chair __________________________________ Dr. Ammon Allred, Committee Member __________________________________ Dr. Charles V. Blatz, Committee Member __________________________________ Dr. Patricia Komuniecki, Dean College of Graduate Studies The University of Toledo August 2011 An abstract of Why Rawlsian Liberalism has Failed and How Proudhonian Anarchism is the Solution by Robert Pook Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in Philosophy University of Toledo August 2011 Liberalism has failed. The paradox in modern society between capitalism and democracy has violated the very principles of liberty, equality, and social justice that liberalism bases its ideology behind. Liberalism, in directly choosing capitalism and private property has undermined its own values and ensured that the theoretical justice, in which its foundation is built upon, will never be. This piece of work will take the monumental, landmark, liberal work, A Theory of Justice, by John Rawls, as its foundation to examine the contradictory and self-defeating ideological commitment to both capitalism and democracy in liberalism. I will argue that this commitment to both ideals creates an impossibility of justice, which is at the heart of, and is the driving force behind liberal theory. In liberalism‟s place, I will argue that Pierre-Joseph Proudhon‟s anarchism, as outlined in, Property is Theft, offers an actual ideological model to achieving the principles which liberalism has set out to achieve, through an adequate and functioning model of justice. -

Paul Ricoeur's Hermeneutics of Symbols: a Critical Dialectic Of

KRITIKE VOLUME FOUR NUMBER TWO (DECEMBER 2010) 1-17 Article Paul Ricoeur’s Hermeneutics of Symbols: A Critical Dialectic of Suspicion and Faith Alexis Deodato S. Itao Introduction ritical theory, which started in Germany through the members of the Frankfurt School1 in the early 1920’s, has inspired a number of non- CGerman philosophical schools and philosophers to establish their own unique critical theories. Paul Ricoeur (1913-2005), who is one of the most celebrated contemporary philosophers in France, is one of those who fashioned a “unique version of critical theory.”2 David Kaplan reveals that Ricoeur is even “committed to a conception of philosophy as critical theory resulting in personal and social transformation and progressive politics.”3 However, Ricoeur’s philosophy as a whole has mainly been considered hermeneutical, that is, one concerned mostly with questions involving interpretation. Emerita Quito ascertains, for instance, that “Ricoeur’s entire philosophy finally centered on hermeneutics.”4 Likewise, Don Ihde confirms how hermeneutics eventually became the “guiding thread which unites” all of Ricoeur’s diverse interests.5 Indeed, Ricoeur devoted much of his writings in 1 Douglas Kellner relates that “the term ‘Frankfurt School’ refers to the work of the members of the Institut für Sozialforschung (Institute for Social Research) which was established in Frankfurt, Germany, in 1923 as the first Marxist-oriented research centre affiliated with a major German university. Under its director, Carl Grünberg, the institute’s work -

The Great Refusal: Herbert Marcuse and Contemporary Social Movements

Excerpt • Temple University Press 1 Bouazizi’s Refusal and Ours Critical Reflections on the Great Refusal and Contemporary Social Movements Peter N. Funke, Andrew T. Lamas, and Todd Wolfson The Dignity Revolution: A Spark of Refusal n December 17, 2010, in a small rural town in Tunisia, an interaction that happens a thousand times a day in our world—the encounter Obetween repression’s disrespect and humanity’s dignity—became a flashpoint, igniting a global wave of resistance. On this particular day, a police officer confiscated the produce of twenty-six-year-old street vendor Mohamed Bouazizi and allegedly spit in his face and hit him. Humiliated and in search of self-respect, Bouazizi attempted to report the incident to the municipal government; however, he was refused an audience. Soon there- after, Bouazizi doused himself in flammable liquid and set himself on fire. Within hours of his self-immolation, protests started in Bouazizi’s home- town of Sidi Bouzid and then steadily expanded across Tunisia. The protests gave way to labor strikes and, for a few weeks, Tunisians were unified in their demand for significant governmental reforms. During this heightened period of unrest, police and the military responded by violently clamping down on the protests, which led to multiple injuries and deaths. And as is often the case, state violence intensified the situation, resulting in mounting pressure on the government. The protests reached their apex on January 14, 2011, and Tunisian president Ben Ali fled the country, ending his twenty- three years of rule; however, the demonstrations continued until free elec- tions were declared in March 2011.