Writing Sample

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Ref : TP/VAL/Q575/A

For Discussion WCDC Paper On 09.01.2018 No.: 2/2018 Proposed Amendments to the Road Improvement Works at Kennedy Road, and the Junction of Queen’s Road East and Kennedy Road, Wan Chai PURPOSE 1. This paper aims to seek Members’ views on the proposed amendments to the Road Improvement Works (“RIW”) following the presentation by the representatives of Hopewell Holdings Limited to Wan Chai District Council on 10 January 2017 regarding the latest development scheme of Hopewell Centre II and the associated RIW amendments. BACKGROUND 2. The original RIW was gazetted in April 2009 and authorized by the Chief Executive in Council in July 2010. The RIW comprises three parts; namely road widening at Kennedy Road, road widening at the junction of Queen’s Road East and Kennedy Road, and road widening at the junction of Spring Garden Lane and Queen’s Road East Note 1. Please refer to the Key Plan in 2009 Gazette at Appendix 1. 3. In order to preserve more trees, during the detailed design of the road work, Hopewell Holdings Limited proposed to amend the RIW at Kennedy Road and at the junction of Queen’s Road East and Kennedy Road. The proposed amendments to the RIW have been submitted to the relevant Government departments for comment and are considered acceptable in principle. On 11 August 2017, the planning application (No. A/H5/408) of the latest development scheme of Hopewell Centre II was approved with conditions by the Metro Planning Committee of the Town Planning Board including an approval condition on the design and implementation of the related RIW. -

Public Waste Recovery Facilities (Central and Wan Chai)

Public Waste Recovery Facilities (Central and Wan Chai) The one-year programme "Mobile Community Recycling Shop" will end on September 16, 2012 (Sunday). Upon the completion of the “Mobile Community Recycling Shop" programme, citizens are encouraged to continue to practice source separation of waste by making good use of the waste recovery facilities at their residential buildings, housing estates or workplaces. For convenience, we have compiled below a list of some public waste recovery facilities in Central and Wan Chai for reference. Please note the exact locations and opening hours of the recovery facilities may be adjusted as per the actual operational situations. Thank you for your kind attention. Three-coloured Recyclables Collection Bins 6) Junction of Ice House Street and Chater 1) Lockhart Road Market Road 2) Outside Sogo Department Store, Hennessy Road 7) Corridor of Central Pier no. 9 3) Pavement near junction of Yee Wo Street and 8) Statue Square,Chater Road(Prince Paterson Street Building) 4) Open space between Statue Square and Prince’s 9) Chater Garden, Chater Road Building (opposite to AIG Tower) 5) In front of Central MTR Station exit C at 18 Des 10) Hong Kong City Hall Voeux Road Central Glass Bottles Collection Point Name Address Working hour Shop S45, basement, East Buddhist Compassion Relief Tue to Sat 10:00 a.m. - 3:00 p.m. Point Centre, 1056 King’s road, Tzu-chi Foundation (except Sun and Mon) Hong Kong 1 Stadium Path, So Kon Po, Olympic House 24 hours Causeway Bay, Hong Kong. Central and Western District Elderly Community Centre - 11/F, Sheung Wan Municipal St. -

Branch List English

Telephone Name of Branch Address Fax No. No. Central District Branch 2A Des Voeux Road Central, Hong Kong 2160 8888 2545 0950 Des Voeux Road West Branch 111-119 Des Voeux Road West, Hong Kong 2546 1134 2549 5068 Shek Tong Tsui Branch 534 Queen's Road West, Shek Tong Tsui, Hong Kong 2819 7277 2855 0240 Happy Valley Branch 11 King Kwong Street, Happy Valley, Hong Kong 2838 6668 2573 3662 Connaught Road Central Branch 13-14 Connaught Road Central, Hong Kong 2841 0410 2525 8756 409 Hennessy Road Branch 409-415 Hennessy Road, Wan Chai, Hong Kong 2835 6118 2591 6168 Sheung Wan Branch 252 Des Voeux Road Central, Hong Kong 2541 1601 2545 4896 Wan Chai (China Overseas Building) Branch 139 Hennessy Road, Wan Chai, Hong Kong 2529 0866 2866 1550 Johnston Road Branch 152-158 Johnston Road, Wan Chai, Hong Kong 2574 8257 2838 4039 Gilman Street Branch 136 Des Voeux Road Central, Hong Kong 2135 1123 2544 8013 Wyndham Street Branch 1-3 Wyndham Street, Central, Hong Kong 2843 2888 2521 1339 Queen’s Road Central Branch 81-83 Queen’s Road Central, Hong Kong 2588 1288 2598 1081 First Street Branch 55A First Street, Sai Ying Pun, Hong Kong 2517 3399 2517 3366 United Centre Branch Shop 1021, United Centre, 95 Queensway, Hong Kong 2861 1889 2861 0828 Shun Tak Centre Branch Shop 225, 2/F, Shun Tak Centre, 200 Connaught Road Central, Hong Kong 2291 6081 2291 6306 Causeway Bay Branch 18 Percival Street, Causeway Bay, Hong Kong 2572 4273 2573 1233 Bank of China Tower Branch 1 Garden Road, Hong Kong 2826 6888 2804 6370 Harbour Road Branch Shop 4, G/F, Causeway Centre, -

21St, 28Th Apr & 12Th, 26Th May 2018 (Sat)(4 Modules X 3 Hours)

Date: 21st, 28th Apr & 12th, 26th May 2018 (Sat)(4 modules x 3 hours) Time: 9:00am - 12:15pm Venue : Lecture Theatre, LG 1, Ruttonjee Hospital, 266 Queen’s Road East, Wan Chai, HK CNE : 3 points per module (to be confirmed) Date Topic Speaker Dr. Edwin K.K. YIP, Specialist in Neurology, Ischemic Stroke for Nurses 21st Ruttonjee & Tang Shiu Kin Hospitals 1 Apr Acute Stroke Service in Hong Kong: Nursing Mr. Wilson AU, APN(ASU), Management and Stroke Nurse Role Ruttonjee & Tang Shiu Kin Hospitals Dr. Selina CHAN, Associate Consultant (Geriatrics), Post stroke rehabilitation— the KEY Elements 28th Ruttonjee & Tang Shiu Kin Hospitals 2 Nursing Care and Management of Patient Apr Mr. CHAN Tak Sing, Registered Nurse (Geri), under Stroke Rehabilitation Service in Ruttonjee & Tang Shiu Kin Hospitals Geriatrics: from Hospital to Community Mr. Alan LAI, Physiotherapist I, Physiotherapy Management in Stroke 12th Ruttonjee & Tang Shiu Kin Hospitals 3 Mr. Benny YIM, Senior Occupational Therapist, May Occupational Therapy in Stroke Rehabilitation Ruttonjee and Tang Shiu Kin Hospitals Mr. CHAN KUI, Chinese Medicine Practitioner, Chinese Medicine Treatment on Stroke HKTBA Chinese Medicine Clinic cum Training 26th Centre of the University of Hong Kong 4 May Ms. POON Zi Ha, Chinese Medicine Practitioner, Chinese Medicine Treatment on Hypertension HKTBA Chinese Medicine Clinic cum Training Centre of the University of Hong Kong Enrollment Deadline: 18th April 2018 Enquiry: 2834 9333 Website: www.antitb.org.hk (Upcoming Event) Seminars on “Ischemic Stroke” for Nurses Objectives a) To strengthen, update and develop knowledge of nurses on the topic of endocrine system. b) To enhance the skills and technique in daily practice. -

Application for Amendment of Plan Under Section 12A of the Town Planning Ordinance

MPC Paper No. Y/H5/5B For Consideration by the Metro Planning Committee on 13.12.2019 APPLICATION FOR AMENDMENT OF PLAN UNDER SECTION 12A OF THE TOWN PLANNING ORDINANCE APPLICATION NO. Y/H5/5 Applicant Yuba Company Limited represented by AECOM Asia Limited Site 1, 1A, 2 and 3 Hillside Terrace, 55 Ship Street (Nam Koo Terrace), 1- 5 Schooner Street, 53 Ship Street (Miu Kang Terrace) and adjoining Government Land, Wan Chai, Hong Kong Site Area About 2,427.9m2 (including about 300m2 government land) Lease Inland Lot (IL) 2140, IL 1940, IL 2272 & Ext. IL 1564, IL1669, IL 2093 R.P. and IL 2093 s.A R.P. - Standard non-offensive trades clause (IL 2140) - Virtually unrestricted except non-offensive trades clause (the remaining ILs) Plan Draft Wan Chai Outline Zoning Plan (OZP) No. S/H5/27 (at the time of submission of the application) Draft Wan Chai OZP No. S/H5/28 currently in force (the zoning of the site remains unchanged) Zonings “Open Space” (“O”) (84%), “Residential (Group C)” (“R(C)”) (14%) and “Government, Institution or Community” (“G/IC”) (2%) Proposed To rezone the application site from “O”, “R(C)” and “G/IC” to Amendment “Comprehensive Development Area” (“CDA”) 1. The Proposal 1.1 The applicant proposes to rezone the application site (the Site) (Plan Z-1) from “O”, “R(C)” and “G/IC” to “CDA” to facilitate a development which comprises residential and commercial uses and preservation of the Grade 1 historical building of Nam Koo Terrace (NKT). The applicant submitted a Proposed Indicative Scheme in the current application to demonstrate that the proposed land uses and development parameters are acceptable. -

District Profiles 地區概覽

Table 1: Selected Characteristics of District Council Districts, 2016 Highest Second Highest Third Highest Lowest 1. Population Sha Tin District Kwun Tong District Yuen Long District Islands District 659 794 648 541 614 178 156 801 2. Proportion of population of Chinese ethnicity (%) Wong Tai Sin District North District Kwun Tong District Wan Chai District 96.6 96.2 96.1 77.9 3. Proportion of never married population aged 15 and over (%) Central and Western Wan Chai District Wong Tai Sin District North District District 33.7 32.4 32.2 28.1 4. Median age Wan Chai District Wong Tai Sin District Sha Tin District Yuen Long District 44.9 44.6 44.2 42.1 5. Proportion of population aged 15 and over having attained post-secondary Central and Western Wan Chai District Eastern District Kwai Tsing District education (%) District 49.5 49.4 38.4 25.3 6. Proportion of persons attending full-time courses in educational Tuen Mun District Sham Shui Po District Tai Po District Yuen Long District institutions in Hong Kong with place of study in same district of residence 74.5 59.2 58.0 45.3 (1) (%) 7. Labour force participation rate (%) Wan Chai District Central and Western Sai Kung District North District District 67.4 65.5 62.8 58.1 8. Median monthly income from main employment of working population Central and Western Wan Chai District Sai Kung District Kwai Tsing District excluding unpaid family workers and foreign domestic helpers (HK$) District 20,800 20,000 18,000 14,000 9. -

Distribution Point of Sold Tourist Octopus

Distribution point of Sold Tourist Octopus All 7-Eleven at MTR stations and the below listed stores G01 Shun Tak Centre, 200 Connaught Rd C, HK-Macau Ferry Terminal, HK Shop 289 on 2nd Floor, Shun Tak Centre, 200 Connaught Road Central, Hong Kong Shop 1C, 1D & 1E, G/F, Queen's Terrace, 1 Queen Street, Sheung Wan, HK Shops F & G, Ground Floor, Hollywood Garden, No. 222 Hollywood Road, Sheung Wan, HK G/F & the Cockloft, No. 298 Des Voeux Road Central, Sheung Wan, Hong Kong Shop B, Ground Floor, 106 Jervois Street, Sheung Wan, Hong Kong G/F., No.40 Elgin Street, Central, Hong Kong G/F, Teng Fuh Commercial Building, 331-333 Queen's Road Central, Central, HK Shop No.106, First Floor, Infinitus Plaza, No.199 Des Voeux Road Central, Hong Kong Shop No. 5, G/F, The Peak Galleria, 118 Peak Road, Hong Kong G/F., Winner House,15 Wong Nei Chung Road, Happy Valley, HK Shop E & F, G/F., New Spring Gdn Mansion, 47-56 Spring Garden Lane, Wanchai, HK G6, G/F, Harbour Centre, 25 Harbour Rd., Wanchai, HK Shop 3, G/F, Professional Bldg., 19-23 Tung Lo Wan Road, HK Shop 2, 20 Luard Road, Wanchai, HK Shop A, G/F, 151 Lockhart Road, Wanchai, HK Portion of shop A, B & C, G/F Sun Tao Bldg, 12-18 Morrison Hill Rd, HK Shop C, G/F Pak Shing Bldg, 168-174 Tung Lo Wan Rd, Causeway Bay, HK Shop C, G/F, Siu Fung Building, 9-17 Tin Lok Lane, Wanchai, HK G4, G/F, Hennessy House (CLI Bldg), 313-317B Hennesy Rd, Wanchai, HK Shop B, G/F, Allied Kajima Bldg., 138 Gloucester Road, Wanchai, HK Shop 3, UG/F., Kam Kwong Mansion, 36-44 King Kwong St, Happy Valley, HK G/F, The Chinese Bank Bldg, 2A Pottinger St, 61-65 Des Voeux Rd C, HK Shop C, G/F, Grand View Comm Bldg, Nos.29-31 Sugar St, Causeway Bay, HK G/F., No. -

Wan Chai Connect Design Group Lead Consultant / Ideation / Buro Happold Multi Disciplinary Engineering / Sustainability Strategy

52 CITIES Wan Chai Connect Design Group Lead Consultant / Ideation / Buro Happold Multi Disciplinary Engineering / Sustainability Strategy Conceptual Architects Urban Design DCMSTUDIOS Architects Conceptual Master Planning Studio B Cost Management Currie and Brown Public Relations Stakeholder Engagement Executive Counsel Real Estate Advisory Knight Frank WAN CHAI Socal Economic Impact Waters Economics BuroHappold marketing and relationships director, Peter Dampier, said: “Serving as a catalyst for regeneration, we hope this sparks serious debate around the provision and ownership of quality public space. Private developers haven’t always historically worked with local communities to create functional but iconic public spaces or looked beyond the site to maximise value.” The Design Group believes that the provision of public space should be considered now in conjunction with the needs and desires of the Wan Chai community. The estimated cost of Wan Chai Connect’s social infrastructure (excluding the extension to the convention centre and new commercial tower) is HK$1.65 Billion. CONNECTS Wan Chai Connect presents a rare, visionary and unmissable opportunity to restore illed as Hong Kong’s equivalent of the New York High Line, Wan Chai Connect is a Hong Kong’s position as a leading World City. vision for the future, weaving old Wan Chai and the harbour, back together. Studio B managing director, Peter Brannan, said: “Taking inspiration from innovative projects B such as New York High Line (an abandoned railway redeveloped into a green walkway Making something out of nothing, Wan Chai Connect is a progressive idea conceptualised to deliver true world-class placemaking, a significant new public space, maximising societal and now the No.1 tourist attraction in New York), Seoul’s Seoullo (a former highway value, connecting the fragmented, and making it safe, enjoyable and smart to walk easily transformed to a sky garden) and Hong Kong Mid-Levels escalators (that has catalysed around Wan Chai. -

Designated 7-11 Convenience Stores

Store # Area Region in Eng Address in Eng 0001 HK Happy Valley G/F., Winner House,15 Wong Nei Chung Road, Happy Valley, HK 0009 HK Quarry Bay Shop 12-13, G/F., Blk C, Model Housing Est., 774 King's Road, HK 0028 KLN Mongkok G/F., Comfort Court, 19 Playing Field Rd., Kln 0036 KLN Jordan Shop A, G/F, TAL Building, 45-53 Austin Road, Kln 0077 KLN Kowloon City Shop A-D, G/F., Leung Ling House, 96 Nga Tsin Wai Rd, Kowloon City, Kln 0084 HK Wan Chai G6, G/F, Harbour Centre, 25 Harbour Rd., Wanchai, HK 0085 HK Sheung Wan G/F., Blk B, Hiller Comm Bldg., 89-91 Wing Lok St., HK 0094 HK Causeway Bay Shop 3, G/F, Professional Bldg., 19-23 Tung Lo Wan Road, HK 0102 KLN Jordan G/F, 11 Nanking Street, Kln 0119 KLN Jordan G/F, 48-50 Bowring Street, Kln 0132 KLN Mongkok Shop 16, G/F., 60-104 Soy Street, Concord Bldg., Kln 0150 HK Sheung Wan G01 Shun Tak Centre, 200 Connaught Rd C, HK-Macau Ferry Terminal, HK 0151 HK Wan Chai Shop 2, 20 Luard Road, Wanchai, HK 0153 HK Sheung Wan G/F., 88 High Street, HK 0226 KLN Jordan Shop A, G/F, Cheung King Mansion, 144 Austin Road, Kln 0253 KLN Tsim Sha Tsui East Shop 1, Lower G/F, Hilton Tower, 96 Granville Road, Tsimshatsui East, Kln 0273 HK Central G/F, 89 Caine Road, HK 0281 HK Wan Chai Shop A, G/F, 151 Lockhart Road, Wanchai, HK 0308 KLN Tsim Sha Tsui Shop 1 & 2, G/F, Hart Avenue Plaza, 5-9A Hart Avenue, TST, Kln 0323 HK Wan Chai Portion of shop A, B & C, G/F Sun Tao Bldg, 12-18 Morrison Hill Rd, HK 0325 HK Causeway Bay Shop C, G/F Pak Shing Bldg, 168-174 Tung Lo Wan Rd, Causeway Bay, HK 0327 KLN Tsim Sha Tsui Shop 7, G/F Star House, 3 Salisbury Road, TST, Kln 0328 HK Wan Chai Shop C, G/F, Siu Fung Building, 9-17 Tin Lok Lane, Wanchai, HK 0339 KLN Kowloon Bay G/F, Shop No.205-207, Phase II Amoy Plaza, 77 Ngau Tau Kok Road, Kln 0351 KLN Kwun Tong Shop 22, 23 & 23A, G/F, Laguna Plaza, Cha Kwo Ling Rd., Kwun Tong, Kln. -

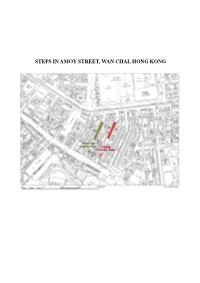

Steps in Amoy Street, Wan Chai, Hong Kong

STEPS IN AMOY STREET, WAN CHAI, HONG KONG Contents 1. Background of the Study 2. Research on the Study Area 2.1 Early History of the Study Area 2.2 Amoy Street: Origins and Early Development 3. The Steps in Amoy Street: Preliminary Findings 3.1 Site Observations 3.2 Land Records 4. Findings of Ground Investigations at No. 186 Queen’s Road East 5. Comparison with Swatow Street 6. Conclusions 7. Bibliography 8. Chronology of Events 9. Plates 1 Pottinger’s Map (1842) 2 Gordon’s Map (1843) 3 Lt Collinson’s Ordnance Survey (1845) 4 Plan of Marine Lot 40 (1859) 5 Plan of Marine Lot 40 (1866) 6 Plan of Marine Lot 40 (1889) 7 Plan of Amoy & Swatow Lanes (1901) 8 Plan of Amoy & Swatow Streets (1921) 9 Plan of Amoy & Swatow Streets (1936) 10 Widening of Amoy Street (1949) 11 Surrender of Sec. A of I.L. 4333 (1949) 12 Plan of Amoy & Swatow Streets (1959) 13 Plan of Swatow Street (1938) 14 Plan of Amoy & Swatow Streets (1963) 15 Plan of Amoy & Swatow Streets (1967) 1 1. Background of the Study 1.1 The Urban Renewal Authority (URA) will redevelop the site of Lee Tung Street and McGregor Street for a comprehensive commercial and residential development with GIC facilities and public open space. Shophouses at 186-190 Queen’s Road East (Grade II) will be conserved for adaptive re-use. The Town Planning Board (TPB) at its meeting on 22 May 2007 approved the Master Layout Plan submitted by URA with conditions including the submission of a conservation plan for the shophouses to be preserved within the site to the satisfaction of the Director of Leisure and Cultural Services or of the TPB. -

A Study on Historical and Architectural Context of Central Market The

A Study on Historical and Architectural Context of Central Market The Hong Kong Institute of Architects July 2005 1.0 The History of the Central Market The historical significance of Central Market may better be understood by first examining the early history of its predecessors, the Canton Bazaar and the former Central Market. As early as in 1842, a market, named Canton Bazaar (廣州市場), was already opened by the Chinese living in the neighbourhood. It was first established at the section of Cochrane and Graham at the foot of the hill near Queen’s Road Central, then moved to Queen’s Road East, where the Supreme Court is now located in Admiralty. At around 1850, the Canton Bazaar was renamed to Central Market (中環街市) and moved to the current site: Between the Praya (now Des Voeux Road Central), Queen’s Road Central, Queen Victoria and Jubilee Streets. It was rebuilt again on years 1858, 1895 and 1938. In 1895, the Government rebuilt the former Central Market to a more elegant, marble structure in western style. Former Central Market on Des Voeux Road Central, c 1928. It was originally built on 1895 and was demolished not long after and then rebuilt in 1938. (Source: Cheng 2001) Former Central Market, the facade on Queens Road Central (Source: www.zazzle.com) In 1938, it was rebuilt again in contemporary western building styles of 1930s, inter alia, the Bauhaus was prevailing. The cost of construction for the new market was $900,000 and it opened again on 1st of May 1939. This new three- storey (plus the roof floor) reinforced concrete structure, with over 200 booths, high ceiling and equipped with many facilities, is regarded as the most advanced market at that time. -

HK TRUSTEES' ASSOCIATION LTD STEP HONG KONG LTD C/O

HK TRUSTEES’ ASSOCIATION LTD STEP HONG KONG LTD c/o Deacons c/o Suite 201 St George’s Building 6/F Alexandra House 2 Ice House Street, Central Chater Road, Central, Hong Kong Hong Kong Tel: 2559 7144 Fax: 2559 7249 Email: [email protected] Website: www.step.orghongkong A SEMINAR ON TRUST STRUCTURES TO HOLD AND PRESERVE THE FAMILY-OWNED BUSINESS Speaker: Christian Stewart (Family Legacy Asia (HK) Ltd) Date: Thursday, 5th March 2009 Time: 6.00 p.m. – 7.00 p.m. Venue: HSBC Theatre, Level 13, 1 Queen’s Road Central, Hong Kong Mr Stewart set up Family Legacy Asia in 2008 to provide Asian families with independent advise that is focused solely on helping families plan and then implement best succession and family governance practices. Mr Stewart will discuss the advantages and disadvantages of using a trust to own the family business and some of the critical tasks that a family needs to engage in. Trusts are often marketed in Asia as a succession planning device, and as a tool that can help keep wealth in a family for more than three generations. Clearly there are certain benefits of using a trust structure that tax and trust advisers can articulate for their clients. There is an often quoted statistic that only one third of family owned businesses will make it into the second-generation and something like a 10% chance of survival into the third generation. The theory of family owned businesses helps to explain these statistics by reference to a “three circle model”, which says that a family owned business is made up of three overlapping systems.