Chapter 3 Pinyon-Juniper and Oak Woodlands Authors: Corrine Dolan and Alix Rogstad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Western Juniper Woodlands of the Pacific Northwest

Western Juniper Woodlands (of the Pacific Northwest) Science Assessment October 6, 1994 Lee E. Eddleman Professor, Rangeland Resources Oregon State University Corvallis, Oregon Patricia M. Miller Assistant Professor Courtesy Rangeland Resources Oregon State University Corvallis, Oregon Richard F. Miller Professor, Rangeland Resources Eastern Oregon Agricultural Research Center Burns, Oregon Patricia L. Dysart Graduate Research Assistant Rangeland Resources Oregon State University Corvallis, Oregon TABLE OF CONTENTS Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................... i WESTERN JUNIPER (Juniperus occidentalis Hook. ssp. occidentalis) WOODLANDS. ................................................. 1 Introduction ................................................ 1 Current Status.............................................. 2 Distribution of Western Juniper............................ 2 Holocene Changes in Western Juniper Woodlands ................. 4 Introduction ........................................... 4 Prehistoric Expansion of Juniper .......................... 4 Historic Expansion of Juniper ............................. 6 Conclusions .......................................... 9 Biology of Western Juniper.................................... 11 Physiological Ecology of Western Juniper and Associated Species ...................................... 17 Introduction ........................................... 17 Western Juniper — Patterns in Biomass Allocation............ 17 Western Juniper — Allocation Patterns of Carbon and -

Annotated Check List and Host Index Arizona Wood

Annotated Check List and Host Index for Arizona Wood-Rotting Fungi Item Type text; Book Authors Gilbertson, R. L.; Martin, K. J.; Lindsey, J. P. Publisher College of Agriculture, University of Arizona (Tucson, AZ) Rights Copyright © Arizona Board of Regents. The University of Arizona. Download date 28/09/2021 02:18:59 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/602154 Annotated Check List and Host Index for Arizona Wood - Rotting Fungi Technical Bulletin 209 Agricultural Experiment Station The University of Arizona Tucson AÏfJ\fOTA TED CHECK LI5T aid HOST INDEX ford ARIZONA WOOD- ROTTlNg FUNGI /. L. GILßERTSON K.T IyIARTiN Z J. P, LINDSEY3 PRDFE550I of PLANT PATHOLOgY 2GRADUATE ASSISTANT in I?ESEARCI-4 36FZADAATE A5 S /STANT'" TEACHING Z z l'9 FR5 1974- INTRODUCTION flora similar to that of the Gulf Coast and the southeastern United States is found. Here the major tree species include hardwoods such as Arizona is characterized by a wide variety of Arizona sycamore, Arizona black walnut, oaks, ecological zones from Sonoran Desert to alpine velvet ash, Fremont cottonwood, willows, and tundra. This environmental diversity has resulted mesquite. Some conifers, including Chihuahua pine, in a rich flora of woody plants in the state. De- Apache pine, pinyons, junipers, and Arizona cypress tailed accounts of the vegetation of Arizona have also occur in association with these hardwoods. appeared in a number of publications, including Arizona fungi typical of the southeastern flora those of Benson and Darrow (1954), Nichol (1952), include Fomitopsis ulmaria, Donkia pulcherrima, Kearney and Peebles (1969), Shreve and Wiggins Tyromyces palustris, Lopharia crassa, Inonotus (1964), Lowe (1972), and Hastings et al. -

The Collection of Oak Trees of Mexico and Central America in Iturraran Botanical Gardens

The Collection of Oak Trees of Mexico and Central America in Iturraran Botanical Gardens Francisco Garin Garcia Iturraran Botanical Gardens, northern Spain [email protected] Overview Iturraran Botanical Gardens occupy 25 hectares of the northern area of Spain’s Pagoeta Natural Park. They extend along the slopes of the Iturraran hill upon the former hay meadows belonging to the farmhouse of the same name, currently the Reception Centre of the Park. The minimum altitude is 130 m above sea level, and the maximum is 220 m. Within its bounds there are indigenous wooded copses of Quercus robur and other non-coniferous species. Annual precipitation ranges from 140 to 160 cm/year. The maximum temperatures can reach 30º C on some days of summer and even during periods of southern winds on isolated days from October to March; the winter minimums fall to -3º C or -5 º C, occasionally registering as low as -7º C. Frosty days are few and they do not last long. It may snow several days each year. Soils are fairly shallow, with a calcareous substratum, but acidified by the abundant rainfall. In general, the pH is neutral due to their action. Collections The first plantations date back to late 1987. There are currently approximately 5,000 different taxa, the majority being trees and shrubs. There are around 3,000 species, including around 300 species from the genus Quercus; 100 of them are from Mexico and Central America. Quercus costaricensis photo©Francisco Garcia 48 International Oak Journal No. 22 Spring 2011 Oaks from Mexico and Oaks from Mexico -

Western Juniper Field Guide: Asking the Right Questions to Select Appropriate Management Actions

Western Juniper Field Guide: Asking the Right Questions to Select Appropriate Management Actions Circular 1321 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover: Photograph taken by Richard F. Miller. Western Juniper Field Guide: Asking the Right Questions to Select Appropriate Management Actions By R.F. Miller, Oregon State University, J.D. Bates, T.J. Svejcar, F.B. Pierson, U.S. Department of Agriculture, and L.E. Eddleman, Oregon State University This is contribution number 01 of the Sagebrush Steppe Treatment Evaluation Project (SageSTEP), supported by funds from the U.S. Joint Fire Science Program. Partial support for this guide was provided by U.S. Geological Survey Forest and Rangeland Ecosystem Science Center. Circular 1321 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DIRK KEMPTHORNE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Mark D. Myers, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2007 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS--the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials con- tained within this report. Suggested citation: Miller, R.F., Bates, J.D., Svejcar, T.J., Pierson, F.B., and Eddleman, L.E., 2007, Western Juniper Field Guide: Asking the Right Questions to Select Appropriate Management Actions: U.S. -

A Vegetation Map of Carlsbad Caverns National Park, New Mexico 1

______________________________________________________________________________ A Vegetation Map of Carlsbad Caverns National Park, New Mexico ______________________________________________________________________________ 2003 A Vegetation Map of Carlsbad Caverns National Park, New Mexico 1 Esteban Muldavin, Paul Neville, Paul Arbetan, Yvonne Chauvin, Amanda Browder, and Teri Neville2 ABSTRACT A vegetation classification and high resolution vegetation map was developed for Carlsbad Caverns National Park, New Mexico to support natural resources management, particularly fire management and rare species habitat analysis. The classification and map were based on 400 field plots collected between 1999 and 2002. The vegetation communities of Carlsbad Caverns NP are diverse. They range from desert shrublands and semi-grasslands of the lowland basins and foothills up through montane grasslands, shrublands, and woodlands of the highest elevations. Using various multivariate statistical tools, we identified 85 plant associations for the park, many of them unique in the Southwest. The vegetation map was developed using a combination of automated digital processing (supervised classifications) and direct image interpretation of high-resolution satellite imagery (Landsat Thematic Mapper and IKONOS). The map is composed of 34 map units derived from the vegetation classification, and is designed to facilitate ecologically based natural resources management at a 1:24,000 scale with 0.5 ha minimum map unit size (NPS national standard). Along with an overview of the vegetation ecology of the park in the context of the classification, descriptions of the composition and distribution of each map unit are provided. The map was delivered both in hard copy and in digital form as part of a geographic information system (GIS) compatible with that used in the park. -

Common Conifers in New Mexico Landscapes

Ornamental Horticulture Common Conifers in New Mexico Landscapes Bob Cain, Extension Forest Entomologist One-Seed Juniper (Juniperus monosperma) Description: One-seed juniper grows 20-30 feet high and is multistemmed. Its leaves are scalelike with finely toothed margins. One-seed cones are 1/4-1/2 inch long berrylike structures with a reddish brown to bluish hue. The cones or “berries” mature in one year and occur only on female trees. Male trees produce Alligator Juniper (Juniperus deppeana) pollen and appear brown in the late winter and spring compared to female trees. Description: The alligator juniper can grow up to 65 feet tall, and may grow to 5 feet in diameter. It resembles the one-seed juniper with its 1/4-1/2 inch long, berrylike structures and typical juniper foliage. Its most distinguishing feature is its bark, which is divided into squares that resemble alligator skin. Other Characteristics: • Ranges throughout the semiarid regions of the southern two-thirds of New Mexico, southeastern and central Arizona, and south into Mexico. Other Characteristics: • An American Forestry Association Champion • Scattered distribution through the southern recently burned in Tonto National Forest, Arizona. Rockies (mostly Arizona and New Mexico) It was 29 feet 7 inches in circumference, 57 feet • Usually a bushy appearance tall, and had a 57-foot crown. • Likes semiarid, rocky slopes • If cut down, this juniper can sprout from the stump. Uses: Uses: • Birds use the berries of the one-seed juniper as a • Alligator juniper is valuable to wildlife, but has source of winter food, while wildlife browse its only localized commercial value. -

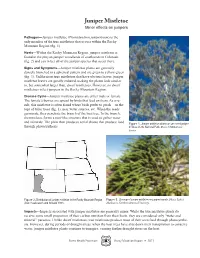

Juniper Mistletoe Minor Effects on Junipers

Juniper Mistletoe Minor effects on junipers Pathogen—Juniper mistletoe (Phoradendron juniperinum) is the only member of the true mistletoes that occurs within the Rocky Mountain Region (fig. 1). Hosts—Within the Rocky Mountain Region, juniper mistletoe is found in the pinyon-juniper woodlands of southwestern Colorado (fig. 2) and can infect all of the juniper species that occur there. Signs and Symptoms—Juniper mistletoe plants are generally densely branched in a spherical pattern and are green to yellow-green (fig. 3). Unlike most true mistletoes that have obvious leaves, juniper mistletoe leaves are greatly reduced, making the plants look similar to, but somewhat larger than, dwarf mistletoes. However, no dwarf mistletoes infect junipers in the Rocky Mountain Region. Disease Cycle—Juniper mistletoe plants are either male or female. The female’s berries are spread by birds that feed on them. As a re- sult, this mistletoe is often found where birds prefer to perch—on the tops of taller trees (fig. 1), near water sources, etc. When the seeds germinate, they penetrate the branch of the host tree. In the branch, the mistletoe forms a root-like structure that is used to gather water and minerals. The plant then produces aerial shoots that produce food Figure 1. Juniper mistletoe plants on one-seed juniper through photosynthesis. in Mesa Verde National Park. Photo: USDA Forest Service. Figure 2. Distribution of juniper mistletoe in the Rocky Mountain Region Figure 3. Closeup of juniper mistletoe on juniper branch. Photo: Robert (from Hawksworth and Scharpf 1981). Mathiasen, Northern Arizona University. Impacts—Impacts associated with juniper mistletoe are generally minor. -

Wakefield 306 2Nd 79500 307 2Nd 71300

WAKEFIELD 306 2ND 79500 307 2ND 71300 405 2ND 56100 406 2ND 81000 409 2ND 8110 508 2ND 124000 302 3RD 83920 303 3RD 131700 304 3RD 112500 305 3RD 25000 306 3RD 139000 307 3RD 56700 308 3RD 58000 403 3RD 10870 405 3RD 35700 501 3RD 144200 503 3RD 17120 704 3RD 33780 804 3RD 920 902 3RD 47800 1600 3RD 15410 1706 3RD 22050 1708 3RD 113870 301 4TH 166700 303 4TH 46400 305 4TH 74900 306 4TH 130300 307 4TH 120300 402 4TH 121900 404 4TH 125800 602 4TH 78100 606 4TH 132500 701 4TH 174540 706 4TH 227000 305 5TH 20500 308 5TH 100970 312 5TH 150800 102 6TH 117950 104 6TH 57100 106 6TH 84360 204 6TH 89200 206 6TH 38200 208 6TH 73900 304 6TH 18490 305 6TH 77130 401 6TH 148000 403 6TH 31750 607 6TH 106500 701 6TH 162000 703 6TH 178500 705 6TH 173300 805 6TH 131900 102 7TH 145000 103 7TH 151500 104 7TH 186800 107 7TH 141500 201 7TH 121200 202 7TH 138300 203 7TH 168900 204 7TH 118800 206 7TH 125500 303 7TH 50600 404 7TH 18170 602 8TH 123100 802 8TH 98700 803 8TH 181400 804 8TH 104900 903 8TH 6080 905 8TH 6080 1001 8TH 6090 1003 8TH 183100 1005 8TH 176700 1007 8TH 167800 1101 8TH 225800 702 9TH 187200 704 9TH 240500 804 9TH 101600 603 10TH 10810 604 10TH 242900 706 10TH 44810 802 10TH 41110 901 10TH 130900 902 10TH 265000 902 10TH 13530 904 10TH 674320 905 10TH 80040 402 BIRCH 79800 403 BIRCH 148900 404 BIRCH 90000 405 BIRCH 107900 406 BIRCH 116100 502 BIRCH 200800 503 BIRCH 145500 504 BIRCH 63000 505 BIRCH 110600 506 BIRCH 216300 602 BIRCH 167600 603 BIRCH 160500 604 BIRCH 96000 605 BIRCH 151100 605 BIRCH 16180 606 BIRCH 6500 607 BIRCH 109300 608 BIRCH -

The World Needs Network Innovation. Juniper Is Here to Help

The world needs network innovation. Juniper is here to help. In a world where the pace of change is accelerating at an unprecedented rate the network has taken on a new level of importance as the vehicle for pulling together our best people, best thinking, and best hope for addressing the critical challenges we face as a global community. The JUNIPER BY THE macro-trends of cloud computing and the mobile Internet NUMBERS hold the potential to expand the reach and power of the network—while creating an explosion of new subscribers, • The world’s top five social media properties new traffic, and new content. In the face of such intense are supported by Juniper demand, this potential cannot be realized with legacy Networks. thinking. Juniper Networks stands as a response and a • The top 10 telecom companies challenge to the traditional approach to the network. in the world run on Juniper Networks. • Juniper Networks is deployed in more than 1,400 national Our Vision government organizations We believe the network is the single greatest vehicle for knowledge, collaboration, and around the world. human advancement that the world has ever known. Now more than ever, the world relies on high-performance networks. And now more than ever, the world needs network • Juniper has over 8,700 innovation to unleash our full potential. employees in 46 worldwide offices, serving over 100 The network plays a central role in addressing the critical challenges we face as a global countries. community. Consider the healthcare industry, where the network is the foundation for new models of mobile affordable care for underserved communities. -

Oaks of the Wild West Inventory Page 1 Nursery Stock Feb, 2016

Oaks of the Wild West Inventory Nursery Stock Legend: AZ = Arizona Nursery TX = Texas Nursery Feb, 2016 *Some species are also available in tube sizes Pine Trees Scientific Name 1G 3/5G 10G 15 G Aleppo Pine Pinus halapensis AZ Afghan Pine Pinus elderica AZ Apache Pine Pinus engelmannii AZ Chinese Pine Pinus tabulaeformis AZ Chihuahua Pine Pinus leiophylla Cluster Pine Pinus pinaster AZ Elderica Pine Pinus elderica AZ AZ Italian Stone Pine Pinus pinea AZ Japanese Black Pine Pinus thunbergii Long Leaf Pine Pinus palustris Mexican Pinyon Pine Pinus cembroides AZ Colorado Pinyon Pine Pinus Edulis AZ Ponderosa Pine Pinus ponderosa AZ Scotch Pine Pinus sylvestre AZ Single Leaf Pine Pinus monophylla AZ Texas Pine Pinus remota AZ, TX Common Trees Scientific Name 1G 3/5G 10G 15 G Arizona Sycamore Platanus wrightii ** Ash, Arizona Fraxinus velutina AZ AZ Black Walnut, Arizona Juglans major AZ AZ Black Walnut, Texas Juglans microcarpa TX Black Walnut juglans nigra AZ, TX Big Tooth Maple Acer grandidentatum AZ Carolina Buckthorn Rhamnus caroliniana TX Chitalpa Chitalpa tashkentensis AZ Crabapple, Blanco Malus ioensis var. texana Cypress, Bald Taxodium distichum AZ Desert Willow Chillopsis linearis AZ AZ Elm, Cedar Ulmus crassifolia TX TX Ginko Ginkgo biloba TX Hackberry, Canyon Celtis reticulata AZ AZ AZ Hackberry, Common Celtis occidentalis TX Maple (Sugar) Acer saccharum AZ AZ Mexican Maple Acer skutchii AZ Mexican Sycamore Platanus mexicana ** Mimosa, fragrant Mimosa borealis Page 1 Oaks of the Wild West Inventory Pistache (Red Push) Pistacia -

![ASHY DOGWEED (Thymophylla [=Dyssodia] Tephroleuca)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9459/ashy-dogweed-thymophylla-dyssodia-tephroleuca-729459.webp)

ASHY DOGWEED (Thymophylla [=Dyssodia] Tephroleuca)

ASHY DOGWEED (Thymophylla [=Dyssodia] tephroleuca) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation Photograph: Chris Best, USFWS U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Corpus Christi Ecological Services Field Office Corpus Christi, Texas September 2011 1 FIVE YEAR REVIEW Ashy dogweed/Thymophylla tephroleuca Blake 1.0 GENERAL INFORMATION 1.1 Reviewers Lead Regional Office: Southwest Regional Office, Region 2 Susan Jacobsen, Chief, Threatened and Endangered Species, 505-248-6641 Wendy Brown, Endangered Species Recovery Coordinator, 505-248-6664 Julie McIntyre, Recovery Biologist, 505-248-6507 Lead Field Office: Corpus Christi Ecological Services Field Office Robyn Cobb, Fish and Wildlife Biologist, 361- 994-9005, ext. 241 Amber Miller, Fish and Wildlife Biologist, 361-994-9005, ext. 247 Cooperating Field Office: Austin Ecological Services Field Office Chris Best, Texas State Botanist, 512- 490-0057, ext. 225 1.2 Purpose of 5-Year Reviews: The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service or USFWS) is required by section 4(c)(2) of the Endangered Species Act (Act) to conduct a status review of each listed species once every five years. The purpose of a 5-year review is to evaluate whether or not the species’ status has changed since it was listed (or since the most recent 5-year review). Based on the 5-year review, we recommend whether the species should be removed from the list of endangered and threatened species, be changed in status from endangered to threatened, or be changed in status from threatened to endangered. Our original listing as endangered or threatened is based on the species’ status considering the five threat factors described in section 4(a)(1) of the Act. -

Redalyc. Germinación Y Establecimiento De Mimosa

Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad ISSN: 1870-3453 [email protected] Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México México Pavón, Numa P.; Ballato-Santos, Jesús; Pérez-Pérez, Claudia Germinación y establecimiento de Mimosa aculeaticarpa var. biuncifera (Fabaceae- Mimosoideae) Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, vol. 82, núm. 2, junio, 2011, pp. 653-661 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Distrito Federal, México Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=42521043023 Abstract Mimosa aculeaticarpa var. biuncifera, spiny drought-deciduous shrub has the potential to be used in restoration projects in degraded semi-arid areas of México. However, basic information that supports this does not exist. The objective of the study was to evaluate the germination conditions and establishment of this species. Germination experiments were realized using 3 factors (scarification, light and temperature). Also, seeds predation for bruquids was registered. We evaluated the effect of light and soil nitrogen on the establishment, for this we considered survival, growth and root nodulation of the shrub seedling. Scarification and temperature were significant dormancybreaking factors. Seeds were not photoblastics and germinative parameters indicated that to 30o C the better results were obtained. Seeds damaged by bruquids not germinate; the infestation was 26.8 % and 4 bruquids species were determined. On high brightness conditions, the highest seedling survival and root growth was registered. The nitrogen fertilization of soil had a significant negative effect on survival and growth of the shrub seedling. These results support the recommendation to use M. aculeaticarpa var. biuncifera in the restoration projects in degraded semi-arid areas in México. Keywords Bruquids, soil fertilization, leguminous plant, seedlings, restoration, xerophilous shrubland.