Firearms in the Family

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Under the Second Amendment

PROTESTS, INSURRECTION, AND THE SECOND AMENDMENT The Gun Rights Movement and “Arms” Under the Second Amendment By Eric Ruben, Assistant Professor, SMU Dedman School of Law, and Fellow, Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law PUBLISHED JUNE 2021 Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law Introduction After Donald Trump supporters breached the U.S. Capitol on January 6 wielding weapons including tasers, chemical sprays, knives, police batons, and baseball bats, Sen. Ron Johnson (R-WI) remarked that the insurrection “didn’t seem . armed.”1 Johnson, who is A-rated by the National Rifle Association (NRA),2 observed, “When you hear the word ‘armed,’ don’t you think of firearms?”3 For many, the answer is likely yes. This essay describes how the gun rights movement has contributed to the conflation of arms and firearms. In doing so, it shows how that conflation is flatly inconsistent with the most important legal context for arms — the Second Amendment. Neglecting non-gun arms obscures how Americans actually own, carry, and use weapons for self-defense and elevates guns over less lethal alternatives that receive constitutional protection under District of Columbia v. Heller.4 Now is the time to place gun rights into the broader Second Amendment context, on the eve of the Supreme Court’s next big Second Amendment case, New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Corlett.5 Heller’s Definition of Arms and Its Potential Implications The Second Amendment protects arms, not firearms,6 and in Heller, the Supreme Court defined an arm as any “[w]eapon[] of offence” or “thing that a man wears for his defence, or takes into his hands,” that is “carr[ied] . -

Nancy Simpson Mornings 5:30A-10A

Call Letters KTTS KSPW KSGF KRVI Format Country Top 40 News Talk Adult Hits/Variety Frequency 94.7 FM 96.5 FM 104.1 FM/1260 AM 106.7 FM Station Country Best 94.7 KTTS Power 96.5 Springfield’s Talk 104.1 106.7 The River DJs 5:30a-10a 6a-10a 6a-9a 6a-10a (Mon-Fri)/10a-1p (Saturday) Nancy & Rick Fotsch & Friends Nick Reed Ace & TJ 10a-3p 10a-3p Sarah Myers 6a-10a (Saturday)/8p-12a (Sunday) Chelsea Julian Syndicated Line Up: Casey Kasem Radio Stations Radio 3p-7p Old School Lunch Hour/ Glenn Beck 9a-12p (Sunday) Commander Tom 3p-6p Dana Loesch Nina Blackwood (Absolutely 80’s) 7p-12a The Ginge Sean Hannity B-Dub 7p-11p Mark Levin Weekends Tino Cochino Ben Shapiro Steve Smith Weekends Katie Chelsea Website ktts.com power965.com ksgf.com 1067theriver.com Core Listeners A 25-49 W 18-34 M 35-64 A 25-44 Core Artists Tim McGraw, Luke Combs, Post Malone, Taylor Swift, News Talk Madonna, Aerosmith, Michael Jackson, Miranda Lambert, Garth Brooks, Justin Bieber, Shawn Mendes, Bon Jovi, Def Leppard, Linkin Park, Phil Carrie Underwood, Blake Shelton, Camilla Cabello, Maroon 5 Collins, Cyndi Lauper, Imagine Dragons, SummitMedia Jason Aldean, Luke Bryan John Mellencamp, 3 Doors Down Format Country 94.7 KTTS is the Ozarks’ Heritage country station; winner of the Country Music Association Small Market Station of the Year (2016,2018), winner of the Academy of Country Music Small Market Station of the Year (2015,2017), and one of 10 radio stations in the entire country to receive a Crystal Award from the National Association of Broadcasters for service for our community. -

Ll Do for Donald Trump …

What They’ll Do for Donald Trump … In Robert Bolt’s 1960 play A Man For All Seasons, an overly ambitious little man named Richard Rich commits perjury against his friend, a great man of conscience, Sir Thomas More – perjury that he knows will send Thomas to his death. And why does he do it? Because Richard Rich needs to be somebody bigger than he is. He needs recognition. He betrays his friend in exchange for a job he thinks will give him status – Attorney General of Wales. After the trial, when Sir Thomas knows he is doomed, he confronts Richard Rich and utters a verse from the Bible – with a twist. “It profits a man nothing to give his soul for the whole world … but for Wales?” – making sure Richard, a status-seeking careerist, understands what he has just done: that he gave his soul not for the whole world – but for a trivial job in a trivial place. None of us is pure. Few of us are as noble as Sir Thomas More. We make accommodations. Sometimes we convince ourselves that our motives are noble, when in fact they’re selfish. But if we’re going to sell out our principles, we should be motivated by something of great significance. Each of us can decide what that might be, what would cause us to abandon our long held beliefs. Selling out always comes with a price. Sir Thomas lived in the 16th century, but his stinging observation holds a message even now, some 500 years later. And so in his final days in office, a question comes to mind about our current president: If it profits a man nothing to give his soul for the whole world … why do it for Donald Trump? Donald Trump no longer fascinates me. -

Benghazi.Pdf

! 1! The Benghazi Hoax By David Brock, Ari Rabin-Havt and Media Matters for America ! 2! The Hoaxsters Senator Kelly Ayotte, R-NH Eric Bolling, Host, Fox News Channel Ambassador John Bolton, Fox News Contributor, Foreign Policy Advisor Romney/Ryan 2012 Gretchen Carlson, Host, Fox News Channel Representative Jason Chaffetz, R-UT Lanhee Chen, Foreign Policy Advisor, Romney/Ryan 2012 Joseph diGenova, Attorney Steve Doocy, Host, Fox News Channel Senator Lindsay Graham, R-SC Sean Hannity, Host, Fox News Channel Representative Darrell Issa, R-CA, Chairman, House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform Brian Kilmeade, Host, Fox News Channel Senator John McCain, R-AZ Mitt Romney, Former Governor of Massachusetts, 2012 Republican Presidential Nominee Stuart Stevens, Senior Advisor, Romney/Ryan 2012 Victoria Toensing, Attorney Ambassador Richard Williamson, Foreign Policy Advisor, Romney/Ryan 2012 ! 3! Introduction: Romney’s Dilemma Mitt Romney woke up on the morning of September 11, 2012, with big hopes for this day – that he’d stop the slow slide of his campaign for the presidency. The political conventions were in his rear-view mirror, and the Republican nominee for the White House was trailing President Obama in most major polls. In an ABC News/Washington Post poll released at the start of the week, the former Massachusetts governor’s previous 1-point lead had flipped to a 6-point deficit.1 “Mr. Obama almost certainly had the more successful convention than Mr. Romney,” wrote Nate Silver, the polling guru and then-New York Times blogger.2 While the incumbent’s gathering in Charlotte was marked by party unity and rousing testimonials from Obama’s wife, Michelle, and former President Bill Clinton, Romney’s confab in Tampa had fallen flat. -

Blueprint for a Better Deal for Black America

Blueprint for a Better Deal for Black America April 2018 A program of the National Center for Public Policy Research 20 F Street NW, Suite 700 Washington, D.C. 20001 NationalCenter.org This publication is dedicated to the memory of Amy Moritz Ridenour, the founding CEO of the National Center for Public Policy Research, without whose support Project 21 wouldn’t exist. Project 21’s Blueprint for a Better Deal for Black America - 2 Executive Summary It has been over a half-century since the enactment of landmark civil rights legislation targeting the scourge of racial discrimination. Unfortunately, too many black families today suffer from a non-racial scourge – conditions that undermine upward mobility and perpetuate unacceptable levels of poverty, crime and other social ills. The vaunted social safety net has become a web that ensnares black families in a vicious cycle of dependency. Project 21, a network of black leaders from across the nation, has identified 10 key areas for reform and offers 57 concrete, budget-neutral recommendations to remove barriers blocking blacks from reaching their full potential and ensuring the American dream is attainable for all. Project 21 Areas of Focus and Key Recommendations: Promoting K–12 Educational Choice: Establish federal needs-based vouchers funded in part through an IRS 1040 voluntary donation check-off. Improve school security through upgrades in entry doors and by allowing trained school personnel access to guns. Improving Higher Education: Require schools to meet minimum graduation rate standards for both general and minority student populations to be eligible for federal student financial aid. -

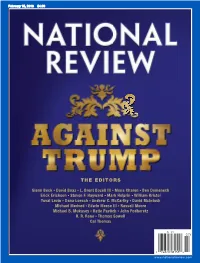

The Editors the Editors

20160215 _ UPC_cover61404-postal.qxd 1/26/2016 10:29 PM Page 1 February 15, 2016 $4.99 THE EDITORS GlennGlenn BeckBeck GG DavidDavid BoazBoaz GG L.L. BrentBrent BozellBozell IIIIII GG MonaMona CharenCharen GG BenBen DomenechDomenech ErickErick EricksonErickson GG StevenSteven F.F. HaywardHayward GG MarkMark HelprinHelprin GG WilliamWilliam KristolKristol YuvalYuval LevinLevin GG DanaDana LoeschLoesch GG AndrewAndrew C.C. McCarthyMcCarthy GG DavidDavid McIntoshMcIntosh MichaelMichael MedvedMedved GG EdwinEdwin MeeseMeese IIIIII GG RussellRussell MooreMoore MichaelMichael B.B. MukaseyMukasey GG KatieKatie PavlichPavlich GG JohnJohn PodhoretzPodhoretz R.R. R.R. RenoReno GG ThomasThomas SowellSowell CalCal ThomasThomas www.nationalreview.com base_milliken-mar 22.qxd 7/21/2015 3:41 PM Page 2 base_milliken-mar 22.qxd 7/21/2015 3:41 PM Page 3 TOC_QXP-1127940144.qxp 1/27/2016 1:50 PM Page 1 Contents FEBRUARY 15, 2016 | VOLUME2 LXVIII, NO. 2 | www.nationalreview.com $4.99 ON THE COVER Page 26 Donald Trump is not Reihan Salam on Bernie Sanders deserving of conservative p. 20 support in the caucuses and primaries. Trump is a BOOKS, ARTS philosophically un moored & MANNERS political opportunist who 41 A MAN IN FULL would trash the broad Clark S. Judge reviews Destiny and Power: The American Odyssey conservative ideological of George Herbert Walker consensus within the THE EDITORS Bush, by Jon Meacham, and The GGlennlenn Beck GG David Boaz GG L.L. BrentBrent BozellBozell IIIIII GG Mona Charen GG Ben Domenech Quiet Man: The Indispensable EErickrick EricksonErickson GG SSteventeven F. Hayward GG MMarkark Helprin GG WWilliamilliam Kristol GOP in favor of a free- YuvalYuval Levin GG DanaDana Loesch GG AndrewAndrew C. -

CQR Tea Party Movement

Res earc her Published by CQ Press, a Division of SAGE CQ www.cqresearcher.com Tea Party Movement Will angry conservatives reshape the Republican Party? he Tea Party movement seemed to come out of nowhere. Suddenly, citizens angry over the multi- billion-dollar economic stimulus and the Obama ad - T ministration’s health-care plan were leading rallies, confronting lawmakers and holding forth on radio and TV. Closely tied to the Republican Party — though also critical of the GOP — the movement proved essential to the surprise victory of Republi - can Sen. Scott Brown in Massachusetts. Tea partiers say Brown’s Tea kettle held high, a Tea Party activist dressed like a election proves the movement runs strong outside of “red states.” Revolutionary War soldier rallies tax protesters in Atlanta on April 15, 2009. It was among several But some political experts voice skepticism, arguing that the Tea protests held in cities around the nation. Party’s fiscal hawkishness won’t appeal to most Democrats and many independents. Meanwhile, some dissension has appeared among tea partiers, with many preferring to sidestep social issues, I such as immigration, and others emphasizing them. Still, the move - N THIS REPORT ment exerts strong appeal for citizens fearful of growing govern - S THE ISSUES ....................243 I ment debt and distrustful of the administration. BACKGROUND ................249 D CHRONOLOGY ................251 E CURRENT SITUATION ........256 CQ Researcher • March 19, 2010 • www.cqresearcher.com AT ISSUE ........................257 Volume 20, Number 11 • Pages 241-264 OUTLOOK ......................259 RECIPIENT OF SOCIETY OF PROFESSIONAL JOURNALISTS AWARD FOR EXCELLENCE N AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION SILVER GAVEL AWARD BIBLIOGRAPHY ................262 THE NEXT STEP ..............263 TEA PARTY MOVEMENT CQ Re search er March 19, 2010 THE ISSUES SIDEBARS AND GRAPHICS Volume 20, Number 11 • Does the Tea Party rep - Tea Partiers Running in MANAGING EDITOR: Thomas J. -

Ted Cruz Is Not a Constitutionalist, and Therefore Cannot Be a Constitutional Conservative

Do you believe in the constitution? In the Bible? Ted Cruz is not a constitutionalist, and therefore cannot be a constitutional conservative. He is an establishment conservative. Neither he nor Rubio are qualified candidates. But the birther question is only the tip of the iceberg: The most common tenets to support Ted Cruz deal with the following questions: Is Ted Cruz Constitutionally able to hold the Office of the United States Presidency? Is Ted Cruz a ‘True Conservative’? Is Ted Cruz devoted to the ‘Word of God’? I will try to answer these questions as shortly as possible, but truth be told, I could do a long dissertation on the matter. The answers to all of those Questions are No, No, and No. I've almost completed the first question, but it's enough to share now. http://www.mediaaccess.hu/userspace/pdf_files/Dispelling%20the%20Myths%20that %20Support%20Ted%20Cruz.pdf http://www.mediaaccess.hu/index.php?module=sourcepage&id=598&lang=1 In #TedCruz own words!! Ted Cruz Said, Obama Not Eligible To Be President; Citizen Parents? “ I am honored that so many Americans want me to run for the office of President. However, my moral convictions require that I state clearly for the record that I am not eligible for the office of president or vice president according to Article II – Section I – Clause V of the U.S. Constitution, which requires that only a Natural Born Citizen of the United States, born of an American Citizen Father, seek or hold these offices. As I was born the son of a Cuban Citizen living in Canada at the time, I am not a Natural Born Citizen of the United States. -

KTTS-Media-Kit-.Pdf

Format Country 94.7 KTTS is the Ozarks’ Heritage country station; winner of the Country Music Association Small Market Station of the Year (2016,2018), winner of the Academy of Country Music Small Market Station of the Year (2015,2017), and one of 10 radio stations in the entire country to receive a Crystal Award from the National Association of Broadcasters for service for our community. KTTS has a regional 100,000 watt signal blanketing Southwest Missouri with the best in Country music and local news/weather 24 hours a day, 7 days a week • News & Weather – hourly from the KTTS 24-Hour News Center • Breaking News – when news breaks, we break in! • Go Patrol Traffic reports mornings & afternoons Monday-Friday every ten minutes from 6am- 8:30am & 4pm-6pm • KTTS Interactive Radar in-studio • Severe weather coverage • KTTS First Alert Forecast Awards 2020 Regional Edward R. Murrow Award | Best Newscast 2020 Missouri Broadcasters Association Certificate of Merit | KTTS Morning Show with Nancy and Rick 2020 Missouri Broadcasters Association First Place, Medium Market Radio | Breaking News 2020 Missouri Broadcasters Association First Place, Breaking Weather Coverage Event 2020 Missouri Broadcasters Association First Place, Podcast | The Toll 2018, 2016 CMA Small Market Station of the Year 2018, 2016 NAB Crystal Award 2017, 2015 ACM Small Market Station of the Year Nancy Simpson Mornings 6a-10a After spending 20 years in the KTTS News department, I am now one half of the KTTS Morning Show, and live in Nixa with my husband and two children. In addition to radio, I love spending time with family, cooking, and attending baseball games (especially St. -

(Un)Building the Wall Reinventing Ourselves As Others in the Post-Truth Era

INTRODUCTION (Un)building the Wall Reinventing Ourselves as Others in the Post-truth Era ROUHOLLAH AGHASALEH Georgia State University Background: Out of Comfort Zones N MY SYLLABI, I write for my students (future teachers) that, unlike many teachers who I romanticize teaching and learning, learning is not always fun. Sometimes we need to feel pains and share our pains to learn. Hopefully, this will make all of us better teachers to lift a bit of a burden from our students’ shoulders and make our pedagogy more accessible. Thinking and writing about post-truth is quite uncomfortable, as it requires self-criticism, critical reflection, and confession. We are trained as professionals to present our arguments tactfully—in a way that would not offend anyone. However, positioning my scholarship in the (post)critical camp, I find this problematic. How can I be critical and not disrupt the unjust structures? How can I challenge the normalized meta-narratives and expect all readers to be happy with my writing? I realize that this professionalism leads us to professional tribalism where we write for those who agree with us and expect recognition from them, which is counter-transformative. How could we make a difference if we only engaged in conversations with those who are already in agreement? bell hooks (1996) has eloquently made the case for why and how education should be transformative. How can I, as an educator, work for transformation and yet be afraid of making myself and my readers uncomfortable? In 2016, I wrote to my #bad_hombre and #nasty_women friends that Trump is old news. -

The Tea Party Movement, Framing, and the US Media

This article was downloaded by: [Jules Boykoff] On: 23 November 2011, At: 08:46 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Social Movement Studies Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/csms20 The Tea Party Movement, Framing, and the US Media Jules Boykoff a & Eulalie Laschever b a Department of Politics and Government, Pacific University, Forest Grove, OR, USA b Department of Sociology, University of California, Irvine, CA, USA Available online: 22 Nov 2011 To cite this article: Jules Boykoff & Eulalie Laschever (2011): The Tea Party Movement, Framing, and the US Media, Social Movement Studies, 10:4, 341-366 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2011.614104 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

Media-Kit.Pdf

Springfield’s Talk 104.1 informs and empowers listeners in the Ozarks with the news and information they want. Listeners depend on it! The station puts a focus on what’s important to listeners in the Ozarks: local news, weather, the economy, events that shape our world, and insight on how those events affect life here in the Ozarks. The station (104.1 FM & 1260 AM) is Springfield’s premier news talk product and the Ozarks’ national news source with updates from Fox News. Springfield’s Talk 104.1 delievers expanded, in-depth coverage on local and state news during the KSGF Mornings with Nick Reed (6a-9a) & provides breaking local news and severe weather coverage using the established brand equity of the KTTS 24-Hour News Center Glenn Beck Mark Levin Dana Loesch Ben Shapiro Sean Hannity Armstrong & Getty 53.8% Female 46.2% Male Household Income $100K-$150K 83% Ages 35-64 Nick Reed Mornings 6a-9a Since high school, I have been behind a microphone, first in music, before moving to talk radio, a natural move being a lover of the format. I am not your typical “political talk show host”… I don’t view one side as always ‘good’ while the other side always ‘bad’, party affiliation doesn’t determine the truth, neither does ‘good intention’. Sarah Myers Producer, Mornings on KSGF 6a-9a “Avery” on Power 96.5 Weekends I have been working with KSGF since 2017 and behind a microphone since the age of 17 where I landed a job in radio. Growing up in Fair Grove, I consider myself a country girl at heart….I love going to the lake, hiking and fishing.