Hidden Baggage: Behavioral Responses to Changes in Airline Ticket Tax Disclosure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Antitrust Implications of Computer Reservations Systems (CRS's) Derek Saunders

Journal of Air Law and Commerce Volume 51 | Issue 1 Article 5 1985 The Antitrust Implications of Computer Reservations Systems (CRS's) Derek Saunders Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc Recommended Citation Derek Saunders, The Antitrust Implications of Computer Reservations Systems (CRS's), 51 J. Air L. & Com. 157 (1985) https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc/vol51/iss1/5 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Air Law and Commerce by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. THE ANTITRUST IMPLICATIONS OF COMPUTER RESERVATIONS SYSTEMS (CRS's) DEREK SAUNDERS THE PASSAGE of the Airline Deregulation Act' dramat- ically altered the airline industry. Market forces, rather than government agencies, 2 began to regulate the indus- try. The transition, however, has not been an easy one. Procedures and relationships well suited to a regulated in- dustry are now viewed as outdated, onerous, and even anticompetitive. The current conflict over carrier-owned computer res- ervation systems (CRS's) represents one instance of these problems.3 The air transportation distribution system re- lies heavily on the use of CRS's, particularly since deregu- lation and the resulting increase in airline activity. 4 One I Pub. L. No. 95-504, 92 Stat. 1705 (codified at 49 U.S.C.A. § 1401 (Supp. 1984)). 2 Competitive Market Investigation, CAB Docket 36,595 (Dec. 16, 1982) at 3. For a discussion of deregulation in general and antitrust problems specifically, see Beane, The Antitrust Implications of Airline Deregulation, 45 J. -

Credit Travel Rewards Catalog Available, You Will Be Advised to Make an Alternate Selection Or May Return Your Points to Your Account

ScoreCard® Bonus Point Program Rules 4) Reservations shall also be subject to airline availability for advance gift shop purchases, gambling, beauty salon/barber shop/spa services, 1. As provided in these rules (“Rules”), account holders (“You” or “you”) earn (1) Point in the ScoreCard® fare category seating , non-refundable type tickets for the travel dates laundry, photographs, email, internet and fax, etc.) are the responsibility Program (“Program”) for every dollar in qualifying purchases that you: (i) charge to an eligible credit card specified. 5) ScoreCard travel services reserves the right to choose the of the Cardholder. 4) Cruises are non-refundable, non-cancelable and non- account covered by the Program (“Account”); and (ii) that appears on your statement during the Program Period. Purchases that are returned do not qualify for Points. No Points are earned for finance charges, fees, airline and routing on which to reserve and ticket Cardholders. transferable. Once redeemed, Bonus Points may not be added back to your cash advances, convenience checks, ATM withdrawals, foreign transaction currency conversion charges or ScoreCard account. 5) Please check with ScoreCard travel representatives Universal First Class/Business Class Ticket insurance charges posted to your account. Contact your financial institution (“Sponsor”) for full details on the Item Points Item # Item Points Item # for any documentation requirements or other restrictions associated Program Period dates during which you are eligible to earn Points. Cardholder is responsible for any overages above the maximum ticket with cruises. It is the guest’s responsibility to obtain appropriate 2. Points can be used to order the merchandise/travel awards (“Award(s)”) available in the current Program. -

Validating Carrier, Interline, and GSA

Validating Carrier, Interline, and GSA Developer Administration Guide August 2014 W Q2 © 2012-2014, Sabre Inc. All rights reserved. This documentation is the confidential and proprietary intellectual property of Sabre. Any unauthorized use, reproduction, preparation of derivative works, performance, or display of this document, or software represented by this document, without the express written permission of Sabre Inc. is strictly prohibited. Sabre and the Sabre logo design and Sabre Travel Network and the Sabre Travel Network logo design are trademarks and/or service marks of an affiliate of Sabre. All other trademarks, service marks, and trade names are owned by their respective companies. DOCUMENT REVISION INFORMATION The following information is to be included with all versions of the document. Project Project Name Number Prepared by Date Prepared Revised by Date Revised Revision Reason Edition No. Revised by Date Revised Revision Reason Edition No. Revised by Date Revised Revision Reason Edition No. • • • Table of Contents 1 Getting Started 1.1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Summary of Changes .................................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.3 About This Guide ........................................................................................................................................... 1-2 2 -

Supplement, ICAO's Policies on Taxation

11/1/02 Transmittal Note SUPPLEMENT TO DOC 8632 ICAO’S POLICIES ON TAXATION IN THE FIELD OF INTERNATIONAL AIR TRANSPORT (Third Edition — 2000) 1. The attached Supplement supersedes all previous Supplements to Doc 8632 and includes information received from Contracting States as to their position vis-à-vis the consolidated Resolution on taxation in the field of international air transport up to 11 January 2002. 2. The Supplement is divided into two parts to better reflect the revised editions. Part A includes the position of States on the consolidated Resolution adopted by the Council on 24 February 1999 as it appears in the Third Edition of Doc 8632 dated 2000. Part B includes the positions of States as contained in Doc 8632, Second Edition, dated January 1994. The Second Edition, now an obsolete document, is reproduced in the Attachment to Part B. 3. Additional information received from Contracting States will be issued at intervals as amendments to this Supplement. SUPPLEMENT TO DOC 8632 — THIRD EDITION ICAO’S POLICIES ON TAXATION IN THE FIELD OF INTERNATIONAL AIR TRANSPORT Information reflecting the status of implementation in Contracting States of Council’s 1999 Taxation Resolutions and Recommendations as notified to ICAO. Published by the authority of the Council JANUARY 2002 (ii) SUPPLEMENT TO DOC 8632 INTERNATIONAL CIVIL AVIATION ORGANIZATION RECORD OF AMENDMENTS TO SUPPLEMENT No. Date Entered by No. Date Entered by The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of ICAO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

08-06-2021 Airline Ticket Matrix (Doc 141)

Airline Ticket Matrix 1 Supports 1 Supports Supports Supports 1 Supports 1 Supports 2 Accepts IAR IAR IAR ET IAR EMD Airline Name IAR EMD IAR EMD Automated ET ET Cancel Cancel Code Void? Refund? MCOs? Numeric Void? Refund? Refund? Refund? AccesRail 450 9B Y Y N N N N Advanced Air 360 AN N N N N N N Aegean Airlines 390 A3 Y Y Y N N N N Aer Lingus 053 EI Y Y N N N N Aeroflot Russian Airlines 555 SU Y Y Y N N N N Aerolineas Argentinas 044 AR Y Y N N N N N Aeromar 942 VW Y Y N N N N Aeromexico 139 AM Y Y N N N N Africa World Airlines 394 AW N N N N N N Air Algerie 124 AH Y Y N N N N Air Arabia Maroc 452 3O N N N N N N Air Astana 465 KC Y Y Y N N N N Air Austral 760 UU Y Y N N N N Air Baltic 657 BT Y Y Y N N N Air Belgium 142 KF Y Y N N N N Air Botswana Ltd 636 BP Y Y Y N N N Air Burkina 226 2J N N N N N N Air Canada 014 AC Y Y Y Y Y N N Air China Ltd. 999 CA Y Y N N N N Air Choice One 122 3E N N N N N N Air Côte d'Ivoire 483 HF N N N N N N Air Dolomiti 101 EN N N N N N N Air Europa 996 UX Y Y Y N N N Alaska Seaplanes 042 X4 N N N N N N Air France 057 AF Y Y Y N N N Air Greenland 631 GL Y Y Y N N N Air India 098 AI Y Y Y N N N N Air Macau 675 NX Y Y N N N N Air Madagascar 258 MD N N N N N N Air Malta 643 KM Y Y Y N N N Air Mauritius 239 MK Y Y Y N N N Air Moldova 572 9U Y Y Y N N N Air New Zealand 086 NZ Y Y N N N N Air Niugini 656 PX Y Y Y N N N Air North 287 4N Y Y N N N N Air Rarotonga 755 GZ N N N N N N Air Senegal 490 HC N N N N N N Air Serbia 115 JU Y Y Y N N N Air Seychelles 061 HM N N N N N N Air Tahiti 135 VT Y Y N N N N N Air Tahiti Nui 244 TN Y Y Y N N N Air Tanzania 197 TC N N N N N N Air Transat 649 TS Y Y N N N N N Air Vanuatu 218 NF N N N N N N Aircalin 063 SB Y Y N N N N Airlink 749 4Z Y Y Y N N N Alaska Airlines 027 AS Y Y Y N N N Alitalia 055 AZ Y Y Y N N N All Nippon Airways 205 NH Y Y Y N N N N Amaszonas S.A. -

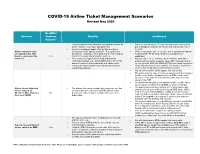

COVID-19 Airline Ticket Management Scenarios Revised May 2020

COVID-19 Airline Ticket Management Scenarios Revised May 2020 Do ARC’s Scenario Systems Benefits Challenges Support? • Ticket number is easily identified, stored and retrieved by • Tracking unused tickets: To track unused tickets, agents may airline, agency, corporation and passenger. pay a third party, maintain an internal tool or manually retrieve • Agency exchanges happen often so this scenario is the data. Airline maintains value already part of the agency workflow. The agency can • Airlines may not be able to extend e-ticket expiration (being able on original ticket. (The perform the exchange in their GDS and the ticketing data to maintain the ET for longer than their standard ticket ticket is considered the Yes is fed to their mid- and back-office systems. expiration). voucher.) • ARC’s systems support this method and allow for • Agency may need to exchange ticket manually. GDS auto- refunds/exchanges (e.g., ticket validity) up to 39 months pricing tool may not be available. Note: ARC understands that based on carrier e-ticket expiration and validity rules. as of early June 2020, the GDSs/ATPCO have made updates to • Tracing the end-to-end life of the transaction is simple allow auto-pricing tools to be utilized. This ability is dependent (old and new tickets). on the airline being able to extend ticket expiration. • Not all airlines and/or GDSs support this functionality. • The airline may not have a consistent way to notify the customer that the value has been transferred to an EMD, as the travel agency’s e-mail address (instead of the passenger’s) may be stored in the PNR • The airline-issued EMD is not reported to ARC, so ARC does not recognize the airline-issued EMD for future exchanges. -

Procedure 20335E: Air Transportation

Controller’s Office Procedure Procedure 20335e: Air Transportation Rules and procedures for the purchase of air travel services, both on public carriers and charter aircraft are based on the requirement that all expenditures of the University must be necessary and reasonable and that the mechanism of payment must be in accordance with state and university procedures. A. Rates Public transportation rates must not exceed those for tourist/coach class accommodations. Business class or premium coach seating such as comfort plus air travel may be granted for international travel under the following circumstances: When the cost does not exceed the lowest available tourist/coach fare. For travel to Western Europe if the business meeting is conducted within three hours of landing. For transoceanic, intercontinental trips involving flight time of more than eight consecutive hours. If the traveler pays the difference. Business class for rail travel may be granted under the following circumstances: When it does not cost more than the lowest available tourist/coach fare (comparison must be attached to the travel reimbursement request). When reserved coach seats are not offered on the route. If the traveler pays the difference. Reimbursement for first class travel is prohibited. Travelers purchasing first class airline tickets will not be reimbursed for the expense from public funds. Travel Protection Insurance for airline tickets is not an allowable expense. Internet Purchases - Internet travel users must be careful when procuring airline tickets. The Internet sites often list only a class code and the user should know the following code designations: Tourist/Coach – B H K L Q T U V W Y Business Class – C J First Class – A D E F J P A.1 Fly America Act If international travel is being charged to a Federal grant or contract, then the “Fly America Act” applies. -

Income Tax (Amendment) Bill 2016 – Bill No

PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF THE FIRST SESSION (2015-2017) OF THE ELEVENTH PARLIAMENT OF GUYANA UNDER THE CONSTITUTION OF THE CO-OPERATIVE REPUBLIC OF GUYANA HELD IN THE PARLIAMENT CHAMBER, PUBLIC BUILDINGS, BRICKDAM, GEORGETOWN 59TH Sitting Friday, 6TH January, 2017 Assembly convened at 2.44 p.m. Prayers [Mr. Speaker in the Chair] PUBLIC BUSINESS GOVERNMENT BUSINESS BILLS – Second Readings INTOXICATING LIQUOR LICENSING (AMENDMENT) BILL 2016 – BILL No. 32/2016 A BILL intituled: “AN ACT to amend the Intoxicating Liquor Licensing Act.” [Minister of Finance] Mr. Speaker: Hon. Members, I must begin by acknowledging our late start and apologising for that. There are two matters which I would like to comment on. First of all, it is to say to Hon. Members, in relation to the information which is to be supplied to questions raised during the debate, that having looked at what is required of us in relation to dissemination of the questions, of the answers to the questions raised, we are proposing that the answers be disseminated by way of soft copy and that hard copy be provided to the questioner. It is proving financially laborious. It will prove that way if we were to supply hard copies of all the answers to all the questions to every Hon. Member in this House. I repeat, we will provide the questioner with the hard copy 1 and to all other Hon. Members we will supply soft copies of the answers. I hope that will prove satisfactory to Hon. Members. Secondly, Hon. Members, the two Chief Whips and I have had a conversation on the progress of our work. -

Air Departure Tax: Who Benefits? Analysis for Scottish Policymakers

air departure tax: who benefits? analysis for scottish policymakers fellow travellers air departure tax: who benefits? About Fellow Travellers fellowtravellers.org Fellow Travellers is a not-for-profit, unincorporated association campaigning for fair and equitable solutions to the growing environmental damage caused by air travel. We aim to protect access to reasonable levels of flying for the less well-off, whilst maintaining aviation emissions within safe limits for the climate. About the authors Leo Murray is the founder of the Free Ride campaign and Director of strategy at climate change charity 10:10. Twitter @crisortunity Charlie Young is an independent researcher with a background in economics and climate change. He focuses on new economics and analyses the socio- economic impacts of policy interventions. Twitter @CMaxwellYoung Acknowledgements This paper was produced with the kind support of Scottish Green Party MSPs. We would also like to thank statisticians at Transport Scotland, HMRC and the CAA for their help compiling and making sense of the data that informs this analysis. Permission to share This document is published under a creative commons licence: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 UK http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/uk/ This paper was first published in June 2017. introduction This paper explores the clearest dimensions of the distributional impacts of the Scottish Government’s planned 50% cut in air passenger taxes, asking the question: who benefits? Our analysis of Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) Passenger Survey data from Scottish airports reveals that this £160m+ annual tax giveaway will predominantly go to line the pockets of wealthy frequent flyers and corporations, while the majority of Scots will lose out. -

Travel Information

Travel Information Visa To enter Indonesia, you are required to possess a passport valid for at least six months from the date of arrival and have proof of return or onward ticketing. Most tourists can obtain a Visa on Arrival (VOA), costs are US$35 for a 30 day stay, or US$15 for a 7 day stay. For some countries there is an additional visa fee. Payment is by cash at the immigration desk upon arrival at the International Bali or Jakarta airport. For some countries this visa-on-arrival does not apply, and people need to apply for a tourist visa in their country of origin before traveling. We highly recommend that you contact your local Indonesian Consulate or Embassy to check requirements for travelers of your nationality and/or passport that you will be traveling on. Vaccinations Please get advice from your local medical center. For some parts of Indonesia malaria prophylactics are recommended as well as booster injections for intestinal diseases and hepatitis A and B. While onboard the Seven Seas, we ensure you will run no risk of "traveler's diseases" as the food is prepared with a high degree of hygiene and all the drinking water comes from bottles. Please ensure your medical insurance covers your vacation. Currency, Cards, Cash The local currency is the Indonesian Rupiah (IDR). Most hotels and restaurants in Bali accept credit cards, but it's always helpful to have some local currency to hand. On Bali there are plenty of ATM cash machines that service most foreign bank cards, most common are those servicing cards with the Cirrus and Maestro logos. -

Civil Aviation and the Federal Government, 1926-1996 (Washington, DC: Federal Aviation Administration, 1998)

1997-2018 Update to FAA Historical Chronology: Civil Aviation and the Federal Government, 1926-1996 (Washington, DC: Federal Aviation Administration, 1998) 1997 January 2, 1997: The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) issued an airworthiness directive requiring operators to adopt procedures enabling the flight crew to reestablish control of a Boeing 737 experiencing an uncommanded yaw or roll – the phenomenon believed to have brought down USAir Flight 427 at Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in 1994. Pilots were told to lower the nose of their aircraft, maximize power, and not attempt to maintain assigned altitudes. (See August 22, 1996; January 15, 1997.) January 6, 1997: Illinois Governor Jim Edgar and Chicago Mayor Richard Daley announced a compromise under which the city would reopen Meigs Field and operate the airport for five years. After that, Chicago would be free to close the airport. (See September 30, 1996.) January 6, 1997: FAA announced the appointment of William Albee as aircraft noise ombudsman, a new position mandated by the Federal Aviation Reauthorization Act of 1996 (Public Law 104-264). (See September 30, 1996; October 28, 1998.) January 7, 1997: Dredging resumed in the search for clues in the TWA Flight 800 crash. The operation had been suspended in mid-December 1996. (See July 17, 1996; May 4, 1997.) January 9, 1997: A Comair Embraer 120 stalled in snowy weather and crashed 18 miles short of Detroit [Michigan] Metropolitan Airport, killing all 29 aboard. (See May 12, 1997; August 27, 1998.) January 14, 1997: In a conference sponsored by the White House Commission on Aviation Safety and Security and held in Washington, DC, at George Washington University, airline executives called upon the Clinton Administration to privatize key functions of FAA and to install a nonprofit, airline-organized cooperative that would manage security issues. -

Case Fsl Cory

NASA CONTRACTOR NASA CR-2227 REPORT CXI IS* <c CASE FSL CORY STUDY OF V/STOL AIRCRAFT IMPLEMENTATION Volume I - Summary by W. J. Portenier and H. M. Webb Prepared by THE AEROSPACE CORPORATION El Segundo, Calif. for Ames Research Center NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION • WASHINGTON, D, C. • MARCH 1973 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. NASA CR-2227 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date March 1973 Study of V/STOL Aircraft Implementation 6. Performing Organization Code Volume I; Summary 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. W. J. Portenier and H. M. Webb 10. Work Unit No. 9. Performing Organization Name and Address The Aerospace Corporation •11. Contract or Grant No. El Segundo, California .'*;.?i£ '•*'. T?~v •' vi?/ .,-'-' .'"if''. '-.'j- •";••: •' ••'•. 'r MAS 2-6473 13. Type of Report and Period Covered 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address Contractor Report National Aeronautics and Space Administration 14. Sponsoring Agency Code Washington, D.C. 15. Supplementary Notes 16. Abstract The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), recognizing the interplay which exists between the technological and institutional aspects of V/STOL implementation, initiated a system study of the interactive elements to assist in planning V/STOL research, and to determine the V/STOL introduction approach that would reasonably provide for an economically viable V/STOL system. This study has identified a high density short haul air market which by 1980 is large enough to support the introduction of an independent short haul air transportation system. This system will complement the existing air transportation system and will provide relief of noise and congestion problems at conventional airports.