Dutchess Dirt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quercus ×Coutinhoi Samp. Discovered in Australia Charlie Buttigieg

XXX International Oaks The Journal of the International Oak Society …the hybrid oak that time forgot, oak-rod baskets, pros and cons of grafting… Issue No. 25/ 2014 / ISSN 1941-2061 1 International Oaks The Journal of the International Oak Society … the hybrid oak that time forgot, oak-rod baskets, pros and cons of grafting… Issue No. 25/ 2014 / ISSN 1941-2061 International Oak Society Officers and Board of Directors 2012-2015 Officers President Béatrice Chassé (France) Vice-President Charles Snyers d’Attenhoven (Belgium) Secretary Gert Fortgens (The Netherlands) Treasurer James E. Hitz (USA) Board of Directors Editorial Committee Membership Director Chairman Emily Griswold (USA) Béatrice Chassé Tour Director Members Shaun Haddock (France) Roderick Cameron International Oaks Allen Coombes Editor Béatrice Chassé Shaun Haddock Co-Editor Allen Coombes (Mexico) Eike Jablonski (Luxemburg) Oak News & Notes Ryan Russell Editor Ryan Russell (USA) Charles Snyers d’Attenhoven International Editor Roderick Cameron (Uruguay) Website Administrator Charles Snyers d’Attenhoven For contributions to International Oaks contact Béatrice Chassé [email protected] or [email protected] 0033553621353 Les Pouyouleix 24800 St.-Jory-de-Chalais France Author’s guidelines for submissions can be found at http://www.internationaloaksociety.org/content/author-guidelines-journal-ios © 2014 International Oak Society Text, figures, and photographs © of individual authors and photographers. Graphic design: Marie-Paule Thuaud / www.lecentrecreatifducoin.com Photos. Cover: Charles Snyers d’Attenhoven (Quercus macrocalyx Hickel & A. Camus); p. 6: Charles Snyers d’Attenhoven (Q. oxyodon Miq.); p. 7: Béatrice Chassé (Q. acerifolia (E.J. Palmer) Stoynoff & W. J. Hess); p. 9: Eike Jablonski (Q. ithaburensis subsp. -

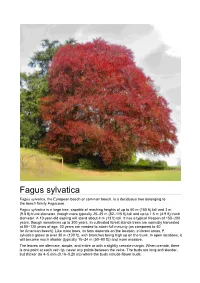

Fagus Sylvatica Fagus Sylvatica, the European Beech Or Common Beech, Is a Deciduous Tree Belonging to the Beech Family Fagaceae

Fagus sylvatica Fagus sylvatica, the European beech or common beech, is a deciduous tree belonging to the beech family Fagaceae. Fagus sylvatica is a large tree, capable of reaching heights of up to 50 m (160 ft) tall and 3 m (9.8 ft) trunk diameter, though more typically 25–35 m (82–115 ft) tall and up to 1.5 m (4.9 ft) trunk diameter. A 10-year-old sapling will stand about 4 m (13 ft) tall. It has a typical lifespan of 150–200 years, though sometimes up to 300 years. In cultivated forest stands trees are normally harvested at 80–120 years of age. 30 years are needed to attain full maturity (as compared to 40 for American beech). Like most trees, its form depends on the location: in forest areas, F. sylvatica grows to over 30 m (100 ft), with branches being high up on the trunk. In open locations, it will become much shorter (typically 15–24 m (50–80 ft)) and more massive. The leaves are alternate, simple, and entire or with a slightly crenate margin. When crenate, there is one point at each vein tip, never any points between the veins. The buds are long and slender, but thicker (to 4–5 mm (0.16–0.20 in)) where the buds include flower buds. The leaves of beech are often not abscissed in the autumn and instead remain on the tree until the spring. This process is called marcescence. This particularly occurs when trees are saplings or when plants are clipped as a hedge (making beech hedges attractive screens, even in winter), but it also often continues to occur on the lower branches when the tree is mature. -

Geobotany Studies

Geobotany Studies Basics, Methods and Case Studies Editor Franco Pedrotti University of Camerino Via Pontoni 5 62032 Camerino Italy Editorial Board: S. Bartha, Va´cra´tot, Hungary F. Bioret, University of Brest, France E. O. Box, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia, USA A. Cˇ arni, Slovenian Academy of Sciences, Ljubljana (Slovenia) K. Fujiwara, Yokohama City University, Japan D. Gafta, “Babes-Bolyai” University Cluj-Napoca (Romania) J. Loidi, University of Bilbao, Spain L. Mucina, University of Perth, Australia S. Pignatti, Universita degli Studi di Roma “La Sapienza”, Italy R. Pott, University of Hannover, Germany A. Vela´squez, Centro de Investigacion en Scie´ncias Ambientales, Morelia, Mexico R. Venanzoni, University of Perugia, Italy For further volumes: http://www.springer.com/series/10526 About the Series The series includes outstanding monographs and collections of papers on a given topic in the following fields: Phytogeography, Phytosociology, Plant Community Ecology, Biocoenology, Vegetation Science, Eco-informatics, Landscape Ecology, Vegetation Mapping, Plant Conservation Biology and Plant Diversity. Contributions are expected to reflect the latest theoretical and methodological developments or to present new applications at broad spatial or temporal scales that could reinforce our understanding of ecological processes acting at the phytocoenosis and landscape level. Case studies based on large data sets are also considered, provided that they support refinement of habitat classification, conservation of plant diversity, or -

John Pastor Illustrated by the Author

What Should a Clever Moose Eat? NATURAL HISTORY, ECOLOGY, AND THE NORTH WOODS OHN ASTOR J FOREWORD BY P BERND HEINRICH What Should a Clever Moose Eat? What Should a Clever Moose Eat? NATURAL HISTORY, ECOLOGY, AND THE NORTH WOODS John Pastor Illustrated by the author Washington | Covelo | London Copyright © 2016 John Pastor All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher: Island Press, 2000 M Street NW, Suite 650, Washington, DC 20036 Island Press is a trademark of The Center for Resource Economics. Library of Congress Control Number: 2015937835 Printed on recycled, acid-free paper Manufactured in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Keywords: Adirondacks, balsam fir, beaver, blueberries, boreal forest, fire, food web, glaciation, ice sheet, Lake Superior, life cycles, life histories, Maine, maple, Minnesota, moose, moraines, natural history, North Woods, pine, pollen analysis, spruce budworms, spruce, tent caterpillar, voyageurs For my grandson, Laszlo Pastor Everything changes; everything is connected; pay attention. —Jane Hirshfield Contents List of Drawings xiii Foreword xv Preface xix Prologue: The Beauty of Natural History xxvii Introduction: The Nature of the North Woods 1 Part I: The Assembly of a Northern Ecosystem and the European Discovery of Its Natural History 19 1. Setting the Stage 21 2. The Emergence of the North Woods 35 3. Beaver Ponds and the Flow of Water in Northern Landscapes 49 4. David Thompson, the Fur Trade, and the Discovery of the Natural History of the North Woods 57 Part II: Capturing the Light 65 5. -

1 Tree Leaves Structure & Function 2019 1

Tree Anatomy: Leaf Structure & Function Dr. Kim D. Coder, Professor of Tree Biology & Health Care / Hill Fellow One of the primary visual keys to tree life and identification are leaves. Leaves provide clues to species, health, and history. Leaves are the workhouses of trees, turning an invisible gas in the air and soil water into carbohydrates using a few essential elements and a sunlight energy source. The term photosynthesis, making life-stuff powered by light, represents the power for 98% of all life on Earth, and demonstrates how tree forms have been sustained over 420 million years. Leaves are the wet cauldrons within which photosynthesis and its associated sustaining processes are contained. Tree leaves provide visual texture, structure and color. Leaves generate white noise from their movement showing the passage of wind and precipitation. Leaves provide an electron source for ecological parasites in the neighborhood. Leaves are one of two active interfaces between a tree’s internal life, and a dry and dangerous environment filled with other living things interfering with each other. Life Energy Tree leaves hold and sustain dense pigment nets for capturing light energy. Leaves generate shade by physically blocking and reflecting light. Leaves act as selective light filters using specific energy wavelengths and passing on the rest of the energy spectrum. A leaf reflects, transmits, absorbs, utilizes, and retransmits light energy. The modified light energy environment or shadow behind / below a leaf opposite the sun, is composed of direct shade (umbra) and indirect shade (penumbra) for a distance based upon leaf size (i.e. shade effect distance). -

Trees and Shrubs for Northern Climates

2019‐01‐15 INTRODUCTION TREES AND SHRUBS Stick with the tried & true? or Sift through the FOR NORTHERN CLIMATES masses of new cultivars? Some change is 200 SHRUB CULTIVARS PLANTED OVER 4 YEARS necessary! Improved global genetics NORTHERN GREEN 2019 New pests Smaller, lower maintenance yards EVALUATION: Determining the impact of climate, soils and pests on PHILIP RONALD, PH.D. long-term plant survival 260 TREE CULTIVARS AT 4 SITES OVER 6 YEARS ERRATIC CLIMATE WEATHER Minnesota: “beachhead” for Is Arctic warming Arctic cold producing hot/cold weather April 5, 2018 Zone map: an extremes in the attempt to U.S.? match plant survival with a The new normal? set of weather > summer drought conditions > April cold snaps > Min. winter temp > Frost free period “Arctic invasion” > Precipitation of April 2018 damaged plants at a time of Do zone maps limited hardiness reflect recent trends? Watch out for Less extreme winter cold extreme cold during More erratic acclimation or weather deacclimation! Dakota Pinnacle Birch – June 2018 Downtown Winnipeg, MB Thief River Falls, MN LANDSCAPE SOIL pH SOILS Bur Oak Typical scenarios Determined by for urban >parent material landscapes: >summer moisture Top-soil often stripped MN is divided: 1/3 alkaline Compaction of 6.5 - 8 subsoil 2/3 acidic Freeman Maple 5.5 – 6.5 Poor drainage Soil alkalinity: Minimal water Major impact on infiltration micro-nutrient availability Little organic matter Severely restricts growth for some Contamination plants Same site – 1 year later 1 2019‐01‐15 PESTS OBJECTIVES Ornamental -

Quantitative Trait Loci Mapping and Analysis of Adaptive Traits in Northern Red Oak (Quercus Rubra L.)

Quantitative trait loci mapping and analysis of adaptive traits in northern red oak (Quercus rubra L.) A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School University of Missouri-Columbia In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Science Presented by Chris Heim Dr. Mark Coggeshall, Thesis Supervisor July 2016 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled: Quantitative trait loci mapping and analysis of adaptive traits in northern red oak (Quercus rubra L.) Presented by Chris Heim, A candidate for the degree of Master of Science, And hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. __________________________________________________ Professor Dr. Mark Coggeshall __________________________________________________ Professor Dr. David Larsen __________________________________________________ Professor Dr. Michele Warmund Acknowledgements I have many people to thank for helping me throughout my studies, as this project would not have been possible without their support. First and foremost I would like to thank my thesis advisor Dr. Mark Coggeshall. Dr. Coggeshall does not know how to say no whenever I need help, resources or advice. He has been a mentor to me since before I started my graduate research, and I consider him a close friend. Secondly, I would like to thank Dr. Jeanne Romero-Severson and her student Arpita Konar. I cannot express the gratitude I feel towards Dr. Romero-Severson for providing both help and patience during my time at the University of Missouri. She took spare time she didn’t have to help a forestry student learn a little about genetics. I want to thank Arpita Konar for working so closely with me on the QTL analysis project. -

Comparative Genomics of Fagaceae

Comparative Genomics of Fagaceae Images.google.com TM www.quia.comLinkage Map www.clipartlord.com Comparative Genomics of Hardwood Tree Species http://www.hardwoodgenomics.org Selection of mapping parents SM2 SM1 Predominant pollinator? Comparative Genomics of Hardwood Tree Species http://www.hardwoodgenomics.org Progeny Exclusion for Full Sib Linkage Mapping Year Acorns SM2 genotyped pollinated 2000 326 101 2003 674 468 2007 362 110 2010 549 399 • All acorns genotyped across 6 microsatellite markers. • Also all potential pollinators within 200 m of SM1 • Exclude all acorns except those pollinated by SM2 • Parentage analysis done with CERVUS. Comparative Genomics of Hardwood Tree Species http://www.hardwoodgenomics.org Pollination rates in SM1 by SM2 across years SM2 paternity (%) across years Our current mapping population composed of 510 full sibs. Comparative Genomics of Hardwood Tree Species http://www.hardwoodgenomics.org SSR markers developed and mapped Developing codominant SSRs Primary amplification test. Temperature gradient. Test of informativeness in parents. Informative markers configurations ab x cd, ef x eg, hk x hk, nn x np, lm x ll SSR Mapping 37 gSSRs ( 26 with CA repeats, 11 with GA repeats) 39 Q. rubra EST-SSRs from FGP ( 181 screened & 148 amplified) 31 Q. robur EST-SSRs ( 113 screened & 99 amplified) 1 EST-SSR from Castanea mollissima. Comparative Genomics of Hardwood Tree Species http://www.hardwoodgenomics.org SSR Framework Map of Q.rubra 1 (6) 2 (8) 3 (1) 4 (2) Comparative Genomics of Hardwood Tree Species http://www.hardwoodgenomics.org 5 (5) 6 (12) 7 (4) 8 (7) Comparative Genomics of Hardwood Tree Species http://www.hardwoodgenomics.org 9 (3) 10 (9) 11 (10) 12 (11) Comparative Genomics of Hardwood Tree Species http://www.hardwoodgenomics.org Comparative Mapping Marker Name Linkage Gr. -

Carpinus Betulus

Carpinus betulus Carpinus betulus in Europe: distribution, habitat, usage and threats R. Sikkema, G. Caudullo, D. de Rigo The common hornbeam (Carpinus betulus L.) is a small-medium deciduous tree which usually grows 20-25 m in height, rarely exceeding 30 m. In winter it is recognisable for its brown leaves which stay attached, dropping only in spring when the new green leaves are starting to come out. Its natural range extends from the Pyrenees to southern Sweden and eastwards to Iran. It is a typical temperate climate species along with deciduous oaks, requiring fairly abundant moisture and tolerant of a range of soil types. It can grow in full to partial sun, but it is also one of the few strongly shade tolerant native trees. Its wood is considered difficult to work due to its density and toughness, so this species has low silvicultural interest, except as a secondary species in mixed stands. In coppice forests it can provide firewood, very appreciated for its high calorific value. The common hornbeam (Carpinus betulus L.) is a small- medium sized deciduous tree normally reaching heights of 20- Frequency 25 metres1-3, although in old growth forests heights can exceed < 25% 25% - 50% 4, 5 30 metres . The crown is irregular, ovoid or conic, becoming 50% - 75% > 75% domed in old trees. The bark is smooth and steel grey, having a Chorology 6 muscled character to its appearance . The leaves are alternate, Native simple, obovate, with serrated margins, 8-10 cm long, opaque to dull green, with prominent parallel veins2. They are quite similar to those of the beech (Fagus sylvatica), but less shiny6. -

Winter Tree Identification Can Inspire Wonder and Curiosity in Students of All Ages

This Winter Tree I.D. Volunteer Enrichment took place at the Litzsinger Road Ecology Center on 02/17/16. This presentation was followed by a winter tree walk on the property to practice using the tools discussed. The walk included tree examples featuring key identifying characteristics discussed in the presentation, examples of younger and older trees of the same species to compare bark changes, and gave people the opportunity to practice using dichotomous keys. 1 The ability to identify trees in the winter is a valuable skill that will strengthen your tree identification ventures throughout the year. Although we often rely on leaves to indicate the tree species, there are several other clues available to us in the winter, if only we know what to look for! Remember to look up, down, and all around, and use all of your senses for these clues. One of your first clues is to determine if the tree is deciduous or coniferous. Does the tree still have green leaves (needles) or have they all dropped? There are only 3 native conifers of Missouri; the bald cypress (deciduous conifer), shortleaf pine, and eastern red cedar. However, the bald cypress loses its leaves in the winter. Because deciduous trees are more common in Missouri, this is one quick way to eliminate some possibilities. You may notice that some trees, particularly oaks and beeches, tend to hang on to some of their leaves in the winter. “Botanists call this retention of dead plant matter marcescence.” Despite being brown and dead, you can usually still see the general shape of the leaf. -

Topics Index

Topics Index A Anthropogenic impacts, 392 Absolute minimum temperature, 12, 14, 27, Appropriate scale, 504, 542 28, 33, 40 Aquatic plants, 81 Accidental species, 367, 371, 373, 417 Aridification, 58, 87, 260 Accuracy (measurement, sampling), 504 Arid subtype (climate), 23, 26, 29, 30 Acidophilous grassland, 350, 351 Assembly rules, 56, 66, 414 Actual vegetation, 243, 249, 250 Association, 80, 113, 185–186, 190–198, 202– Adaptation analysis, xxii, xxvii, 325–327 205, 246, 261–263, 270, 274, 279–282, Adaptive specialization, 56 287, 293, 294, 299, 309, 335, 351, 352, Aerenchyma, 326 357–361, 364, 365, 368, 371, 374, 376– Afforestation, 495 382, 409–412, 414–417, 419, 462–468 African Plants Database, 318 Atlantic forest, 475–495, 534, 536 Agricultural land, 500 Austral climate, 23 Agroforestry, 78, 500 Autecology, xxviii, xxx, xxxiii Alga, 390 Auto-succession, 216, 218–220 Algorithm, 334, 380, 409, 415 Average continent (vegetation), 10 Alien species, 448, 476 Alliance, 106, 261, 269, 280, 287, 309, 325, 332, 350, 352, 357, 360, 364, 365, 368, 374, 376, 377, 379, 380, 466–468 B Allometry, allometric equation, 502–506, 511, Bailey system (climatic), 179 512 Bamboo, 196, 450, 456 Allopatric speciation, 325 Bare land, 502, 504–506, 509, 511, 512 Allophytes, 533 Bark, 106, 107, 111, 196, 258 Alpine belt, 35, 37, 46, 316, 458 Basal belt (altitudinal), 133 Altitudinal belt, 35, 37, 185, 186, 196, 199, 229 Basophilous species, 337 Amphibious vegetation, 315–328 Beech forest, 246, 261, 373, 391, 419, 494, 539 Analysis of variance, 480 Below-ground (strategies, traits), 58 Anglo-Saxon world, 407, 409, 411 Belt (altitudinal), 35, 37, 185, 186, 196, 199, Anmoor, 359, 383, 386 229 Annual plants, 326, 542 Belt (bioclimatic), 35, 36, 261, 316 Annual turf, 323 Bioclimate, 38, 170, 287 Anomaly (climatic), 20, 29 Bioclimatic analysis, xxii, xxv, 260–262 Anthropocene, 534 Bioclimatic zonation, 3–46 Anthropogenic grassland, 332 Biocoenosis, 132, 413 © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2016 549 E.O. -

Trees in Winter

Trees In Winter By Gretchen Spencer, Fairfax Master Gardener The cold, short days of winter offer a wonderful time to observe the trees in our neighborhoods and parks. While the evergreen trees such as the Southern magnolias, hollies, Eastern redcedars, pines, spruces and arborvitae seem to take center stage, for me it is the deciduous trees that garner the most attention. Winter reveals their wonderful artistic structure, colorful bark and vestiges of the growing season such as seed pods and, most importantly, the buds that hold next year’s leaves and by author flowers. Winter poses its own challenges for deciduous trees, such photo: Winter tree architectural silhouette as the cold and lack of water (although here in the Washington D.C. area, we’ve been inundated with rain!). However, trees have several marvelous and complex adaptations that allow them to survive in harsh conditions. First, as everyone knows, trees drop their leaves in the fall to prevent water loss and winter injury, spurred on by the photoperiod, or reduction of daylight. The gradual loss of daylight allows time for the trees to adapt to the coming cold. When the leaves fall, a special layer of cells called the abscission layer grows at the base of each leaf stem to protect it. However, some trees retain their dead brown or tan leaves well into winter or until new growth pushes them off in the spring. This condition, called marcescence, is not well understood. I have noticed this on young beech trees and some varieties of oaks. Some theories are that maintaining the leaves prevents animals from browsing on them, protects leaf buds from drying out or desiccation or provides a nutrient layer for the tree when they by author drop in the spring.