John Pastor Illustrated by the Author

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quercus ×Coutinhoi Samp. Discovered in Australia Charlie Buttigieg

XXX International Oaks The Journal of the International Oak Society …the hybrid oak that time forgot, oak-rod baskets, pros and cons of grafting… Issue No. 25/ 2014 / ISSN 1941-2061 1 International Oaks The Journal of the International Oak Society … the hybrid oak that time forgot, oak-rod baskets, pros and cons of grafting… Issue No. 25/ 2014 / ISSN 1941-2061 International Oak Society Officers and Board of Directors 2012-2015 Officers President Béatrice Chassé (France) Vice-President Charles Snyers d’Attenhoven (Belgium) Secretary Gert Fortgens (The Netherlands) Treasurer James E. Hitz (USA) Board of Directors Editorial Committee Membership Director Chairman Emily Griswold (USA) Béatrice Chassé Tour Director Members Shaun Haddock (France) Roderick Cameron International Oaks Allen Coombes Editor Béatrice Chassé Shaun Haddock Co-Editor Allen Coombes (Mexico) Eike Jablonski (Luxemburg) Oak News & Notes Ryan Russell Editor Ryan Russell (USA) Charles Snyers d’Attenhoven International Editor Roderick Cameron (Uruguay) Website Administrator Charles Snyers d’Attenhoven For contributions to International Oaks contact Béatrice Chassé [email protected] or [email protected] 0033553621353 Les Pouyouleix 24800 St.-Jory-de-Chalais France Author’s guidelines for submissions can be found at http://www.internationaloaksociety.org/content/author-guidelines-journal-ios © 2014 International Oak Society Text, figures, and photographs © of individual authors and photographers. Graphic design: Marie-Paule Thuaud / www.lecentrecreatifducoin.com Photos. Cover: Charles Snyers d’Attenhoven (Quercus macrocalyx Hickel & A. Camus); p. 6: Charles Snyers d’Attenhoven (Q. oxyodon Miq.); p. 7: Béatrice Chassé (Q. acerifolia (E.J. Palmer) Stoynoff & W. J. Hess); p. 9: Eike Jablonski (Q. ithaburensis subsp. -

Planet Asian America

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2001 Planet Asian America Mari J. Matsuda Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] Copyright 2001, Mari J. Matsuda. Reprinted from Asian-American Law Journal, Vol. 8, No. 1, by permission of the Regents of the University of California. This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/318 8 Asian L.J. 169-186 (2001) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons GEORGETOWN LAW Faculty Publications March 2010 Planet Asian America* 8 Asian L.J. 169-186 (2001) Mari J. Matsuda Professor of Law Georgetown University Law Center [email protected] This paper can be downloaded without charge from: Scholarly Commons: http://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/318/ Posted with permission of the author *Copyright 2001, Mari J. Matsuda. Reprinted from Asian-American Law Journal, Vol. 8, No. 1, by permission of the Regents of the University of California. Planet Asian America* Marl Matsudat When we were kids, we played on Kochi-san's truck: an old blue pick-up that carried a permanent smell of cut grass, gasoline, and bug killer. I did not understand until many years later how special those Okinawan Issei gardeners were, working all day on other people's lawns, coming home at night to read Marx and Lenin.1 We learned from them not the theory, but the practice: the dignity in manual labor, the intelligence of workers, the reflexive generosity toward others, the doing of everything - from odori, 2 to building a club house, to Marxist study - in a group. -

IIT Magazinesummer 2017

SUMMER 2017 IIT Magazine Letter from the President On May 13, 2,799 students became members of the Illinois Tech Class of 2017. At the Commencement ceremony held at Ed Glancy Field on Mies Campus, I looked at the many faces representing a multitude of cultures within our academic community. They reminded me of our university's continuum of success as our students transform into alumni leaders across the globe. Some of our recent graduates are introduced in this issue of IIT Magazine on pages 4–5 [read their bio sketches at magazine.iit.edu]. All are ambitious and have discovered ways to further develop their passions in business, engineering, law, psychology, and writing. National Academy of Engineering inductee Sam Pitroda (M.S. EE ’66), who helped to lead the telecommunications revolution in India, is profiled [pages 12–13] as is Robin Chaurasiya (PPPS, PSYC ’06), recipient of Illinois Tech’s 2017 International Award of Merit [pages 10–11]. Robin heads the Mumbai (India)-based nonprofit Kranti, a home for young women from red-light areas. Four Kranti students are now enrolled in various universities thanks to an educational program that Robin, a finalist for the 2016 Global Teacher Prize, has created. You can meet new Institute of Design Dean Denis Weil (M.Des. ’01), who discusses design’s role in society today [page 21]. Weil has led design efforts within the corporate sector as well as the nonprofit sector, bringing extensive and varied work experiences that will further advance ID’s international impact. As the university makes strides across the globe through our alumni and faculty, Illinois Tech also continues to merit recognition closer to home. -

The Newberry Annual Report 2019–20

The Newberry A nnua l Repor t 2019–20 30 Fall/Winter 2020 Letter from the Chair and the President Dear Friends and Supporters of the Newberry, The Newberry’s 133rd year began with sweeping changes in library leadership when Daniel Greene was appointed President and Librarian in August 2019. The year concluded in the midst of a global pandemic which mandated the closure of our building. As the Newberry staff adjusted to the abrupt change of working from home in mid-March, we quickly found innovative ways to continue engaging with our many audiences while making Chair of the Board of Trustees President and Librarian plans to safely reopen the building. The Newberry David C. Hilliard Daniel Greene responded both to the pandemic and to the civil unrest in Chicago and nationwide with creativity, energy, and dedication to advancing the library’s mission in a changed world. Our work at the Newberry relies on gathering people together to think deeply about the humanities. Our community—including readers, scholars, students, exhibition visitors, program attendees, volunteers, and donors—brings the library’s collection to life through research and collaboration. After in-person gatherings became impossible, we joined together in new ways, connecting with our community online. Our popular Adult Education Seminars, for example, offered a full array of classes over Zoom this summer, and our public programs also went online. In both cases, attendance skyrocketed, and we were able to significantly expand our geographic reach. With the Reading Rooms closed, library staff responded to more than 450 research questions over email while working from home. -

San Josã© Studies, November 1976

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks San José Studies, 1970s San José Studies 11-1-1976 San José Studies, November 1976 San José State University Foundation Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sanjosestudies_70s Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation San José State University Foundation, "San José Studies, November 1976" (1976). San José Studies, 1970s. 6. https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sanjosestudies_70s/6 This Journal is brought to you for free and open access by the San José Studies at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in San José Studies, 1970s by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SAN .JOSE Volume II, Number 3 ARTICLES Poetry, Revolution, and the Age of Paine . 6 Roy Harvey Pearce The "tendentiousness" of ideology precludes successful poetry The Ethnic Voice in American Poetry ........................ 26 Arnold Rampersad Poetry - the best language of truth for America's minorities From Colonial to Revolutionary: The Modern American Woman Poet . 37 Barbara Charlesworth Gelpi Poetry as insight into socio-psychic experience The Regional Incentive: Reflections on the Power of Place in Contemporary Literature . 51 William Everson Locality as an adjunct of human personality Andrew P. Hill and the Big Basin, California's First State Park . 70 Carolyn De Vries The birth of the "Save the Redwoods" Movement A Frontier Agrarian Settlement: San Jose de Guadalupe, 1777-1850 . 93 Daniel J. Garr California's first civilian settlement California State Normal School: The First Years in San Jose ......... 106 Benjamin F. Gilbert The beginning of public higher education in California STUDIES November 197 6 The United States Army's First Flirtation with the Bicycle ......... -

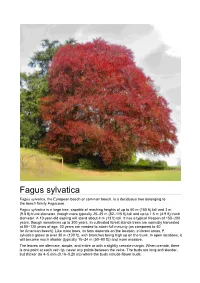

Fagus Sylvatica Fagus Sylvatica, the European Beech Or Common Beech, Is a Deciduous Tree Belonging to the Beech Family Fagaceae

Fagus sylvatica Fagus sylvatica, the European beech or common beech, is a deciduous tree belonging to the beech family Fagaceae. Fagus sylvatica is a large tree, capable of reaching heights of up to 50 m (160 ft) tall and 3 m (9.8 ft) trunk diameter, though more typically 25–35 m (82–115 ft) tall and up to 1.5 m (4.9 ft) trunk diameter. A 10-year-old sapling will stand about 4 m (13 ft) tall. It has a typical lifespan of 150–200 years, though sometimes up to 300 years. In cultivated forest stands trees are normally harvested at 80–120 years of age. 30 years are needed to attain full maturity (as compared to 40 for American beech). Like most trees, its form depends on the location: in forest areas, F. sylvatica grows to over 30 m (100 ft), with branches being high up on the trunk. In open locations, it will become much shorter (typically 15–24 m (50–80 ft)) and more massive. The leaves are alternate, simple, and entire or with a slightly crenate margin. When crenate, there is one point at each vein tip, never any points between the veins. The buds are long and slender, but thicker (to 4–5 mm (0.16–0.20 in)) where the buds include flower buds. The leaves of beech are often not abscissed in the autumn and instead remain on the tree until the spring. This process is called marcescence. This particularly occurs when trees are saplings or when plants are clipped as a hedge (making beech hedges attractive screens, even in winter), but it also often continues to occur on the lower branches when the tree is mature. -

Only the River Remains: History and Memory of the Eastland Disaster in the Great Lakes Region, 1915 – 2015

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 8-2016 Only the River Remains: History and Memory of the Eastland Disaster in the Great Lakes Region, 1915 – 2015 Caitlyn Perry Dial Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Dial, Caitlyn Perry, "Only the River Remains: History and Memory of the Eastland Disaster in the Great Lakes Region, 1915 – 2015" (2016). Dissertations. 1960. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/1960 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ONLY THE RIVER REMAINS: HISTORY AND MEMORY OF THE EASTLAND DISASTER IN THE GREAT LAKES REGION, 1915 – 2015 Caitlyn Perry Dial, Ph.D. Western Michigan University, 2016 On July 24, 1915, the passenger boat Eastland capsized while docked in the Chicago River, killing 844 of its 2,500 passengers. The Eastland Disaster remains the greatest loss-of-life tragedy on the Great Lakes. Using museum exhibits, government documents, trial transcripts, period newspapers, oral interviews, images, ephemera, and popular culture materials, this study examines the century after the disaster in terms of the place the Eastland has held in regional and national public memory. For much of that period, the public memory of the tragedy had been lost, but private memories survived through storytelling within the families of survivors, rescuers, and victims. -

Geobotany Studies

Geobotany Studies Basics, Methods and Case Studies Editor Franco Pedrotti University of Camerino Via Pontoni 5 62032 Camerino Italy Editorial Board: S. Bartha, Va´cra´tot, Hungary F. Bioret, University of Brest, France E. O. Box, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia, USA A. Cˇ arni, Slovenian Academy of Sciences, Ljubljana (Slovenia) K. Fujiwara, Yokohama City University, Japan D. Gafta, “Babes-Bolyai” University Cluj-Napoca (Romania) J. Loidi, University of Bilbao, Spain L. Mucina, University of Perth, Australia S. Pignatti, Universita degli Studi di Roma “La Sapienza”, Italy R. Pott, University of Hannover, Germany A. Vela´squez, Centro de Investigacion en Scie´ncias Ambientales, Morelia, Mexico R. Venanzoni, University of Perugia, Italy For further volumes: http://www.springer.com/series/10526 About the Series The series includes outstanding monographs and collections of papers on a given topic in the following fields: Phytogeography, Phytosociology, Plant Community Ecology, Biocoenology, Vegetation Science, Eco-informatics, Landscape Ecology, Vegetation Mapping, Plant Conservation Biology and Plant Diversity. Contributions are expected to reflect the latest theoretical and methodological developments or to present new applications at broad spatial or temporal scales that could reinforce our understanding of ecological processes acting at the phytocoenosis and landscape level. Case studies based on large data sets are also considered, provided that they support refinement of habitat classification, conservation of plant diversity, or -

Jun Fujita Cabin

NFS Form 10-900 ———'——————————— f _____ 0MB No. 1024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Inter National Park Service National Register of Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for not applicable." F9r functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategpries from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Fujita, Jun Cabin other names/site number Sackett Cabin, Wendt Cabin 2. Location street & number Wendt Island, Voyageurs National Park (VOYA) CD not for publication city or town Ranier X vicinity state Minnesota code MN county St. Louis code 137 zip code 56668 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this Gu nomination LJ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property D meets D does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant LJ nationally LJ statewide Q locally. -

Nisei Combat

PACIFIC CITIZEN 2 SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH, b i s; no- SATURDAY, JULY 15, 1944 Price: Five Cents Nisei CombatUni tDri vesonLi vornoPort Story Hunt Leads of the Week Report 442nd Combat Team WRA Centers Japanese Ameri cans Wi pe Engaged i n InitialTest i n In Relocati on OutGerman Sniper Alli ed Campaign for Italy gifaoj, Received Nest of 100th Infantry Spearheads as largest Number WITH THE FIFTH ARMY pondent reported that Lieut. Crack Attack Encwes i n April IN ITALY—An outfit of engin- Walter Matsumoto of Honolulu, Nisei Engaged i n Violent Figh ting on Plains eers, attached to the Japanese Cpl. Fuji oka American Tadashi of Seattle, Below Strategic City; by Fifth Army depar- unit now i n action Wash., and a sergeant were Cited Th e against the on WASHINGTON — war Germans on the reconnaissance wh en a sniper ts of 1,517 evacuees from Fifth Army front below Livor- opened up on them, k i lling the ROME—Th e Fifth Array announced officially on July 10 centers on i ndefinite no, wh i ch switched from the sergeant. Th e lieutenant and that the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, composed entirely of station ending business of repairing roads Inveg during the month and corporal called for aid from a American soldiers of Japanese ancestry, i s participating i n the were reported thi s bridges and wiped out some Ger- platoon h eaded by Sgt. Harold April 30,1944, man snipers, was the talk of a Fifth Army's attacks along the west coast sector of Italy to- relocation planning Tsukuno of Seattle. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE DATE: August 4, 2020

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE DATE: August 4, 2020 CONTACT: [email protected] 1882 Foundation Supports the Passing of the Great American Outdoors (GAOA) Act in Congress [H.R. 7092 (Cunningham D-SC-1)] Washington, D.C. August 4, 2020 — The 1882 Foundation applauds the signing of the Great American Outdoors Act (GAOA) Act into law from the President. According to the National Parks Conservation Association (NPCA), the National Park System has, for years, experienced severe underfunding, causing a reduction in staffing and a growing backlog of nearly $12 billion in needed repairs. This has made it extremely difficult for employees to preserve our national parks, and has prevented a growing number of visitors from having the park experiences they deserve. The GAOA provides up to $9.5 billion in funds over five years to address priority repairs in more than 400 national parks and other public lands. In addition, the act will provide permanent funding for the Land and Water Conservation Fund. More importantly, efforts to preserve the United States’ national parks and historic landmarks are inseparable from the fight to remember and honor Asian American contributions to the development of our nation. Sites such as Alaska’s Kake Cannery, where Asian American migrant workers struggled against early forms of discrimination and segregation, and California’s Forty Acres, where Filipino farm workers protested alongside Cesar Chavez for better working conditions, honor the enduring legacy that Asian Americans have left on the greater American story through our national parks and national landmarks system. And places such as the Heart Mountain Relocation Center — where 13,397 Japanese Americans were interned during WWII — offer remembrance for the enduring struggle for Asian American equality. -

Dutchess Dirt

Dutchess Dirt A gardening newsletter from: Issue #152, February 2020 LEAVES ON TREES IN WINTER By Joyce Tomaselli, CCEDC Community Horticulture Resource Educator The familiar sequence of leaves turning colors on deciduous trees in Autumn is predictable and rarely changes. Occasionally an extreme drought will affect the intensity of color and speed the sequence, but it always happens. When days get shorter and temperatures cool, senescence is triggered. Senescence is a series of events which prepares a plant for dormancy. During spring and summer leaves have been manufacturing the foods necessary for trees to grow. In Autumn starches and proteins are broken down into sugars and amino acids; these are then reabsorbed into twigs, bark, sapwood and roots for winter storage. This process causes leaves colors to change as the green from chlorophyll declines and the yellows and oranges from carotenoids shine through more brightly. Then the browns from tannins become more visible. As leaf senescence progresses an abscission layer is formed at the base of the leaf petioles where they attach to twigs. Usually before winter the leaves fall off. But not always. If you look around the landscape now you’ll see some trees and shrubs that have retained their leaves. They are exhibiting marcescence, a trait of retaining plant parts after they are dead and dry, usually leaves but sometimes other parts too such as old flowers. (The term "marcescence" comes from a Latin word meaning February 2020 Page 1 "to shrivel”.) These plant parts didn’t develop an abscission layer and will remain attached until spring bud growth pushes them free.