UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sl No Name of Developer/Investor Manufcturer Location Taluk District Nos of Wtgs Hub Height in M Wegs Rating (KW) Total Installe

COMMISSIONED WIND POWER PROJECTS IN KARNATAKA As on 31.07.2021 Sl No Name of Developer/Investor Manufcturer Location Taluk District Nos of Hub WEGs Total Date of WTGs height rating installed Commissioning in M (KW) capacity in MW 1 Victory Glass And Industries NEPC-MICON Kappatagudda Mundargi Gadag 6 30 225 1.350 28-Mar-96 Ltd 2 R P G Telecom Ltd BONUS Hanumasagar Kustagi Koppal 6 40 320 1.920 27-Mar-97 3 Kirloskar Electric Company WEG(UK) Hargapurgad Hukkeri Belgaum 5 35 400 2.000 00-Jan-00 Ltd 4 Victory Glass And Industries NEPC-MICON Kappatagudda Mundargi Gadag 2 30 225 0.450 28-Sep-97 Ltd 5 Jindal Aluminium Ltd ENERCON Madakaripura Chitradurga Chitradurga 10 50 230 2.300 28-Sep-97 6 Jindal Aluminium Ltd ENERCON Madakaripura Chitradurga Chitradurga 8 50 230 1.840 09-Jan-98 7 ICICI Bank Ltd RES-AWT-27 Girgoan Chikkodi Belgaum 12 43 250 3.000 31-Mar-98 8 Indo Wind Energy Ltd NEPC-INDIA Mallasamudraum Gadag Gadag 8 30 225 1.800 31-Mar-98 9 Indo Wind Energy Ltd NEPC-INDIA Mallasamudraum Gadag Gadag 1 30 250 0.250 31-Mar-98 10 Indo Wind Energy Ltd NEPC-INDIA Belathadi Gadag Gadag 1 35 400 0.400 31-Mar-98 11 Indo Wind Energy Ltd NEPC-INDIA Belathadi Gadag Gadag 1 30 225 0.225 11-Sep-98 12 Indo Wind Energy Ltd NEPC-INDIA Belathadi Gadag Gadag 1 30 225 0.225 18-Sep-98 13 Indo Wind Energy Ltd NEPC-INDIA Belathadi Gadag Gadag 1 35 400 0.400 26-Nov-98 14 Indo Wind Energy Ltd NEPC-INDIA Belathadi Gadag Gadag 1 35 400 0.400 10-Dec-98 15 Indo Wind Energy Ltd. -

HŒ臬 A„簧綟糜恥sµ, Vw笑n® 22.12.2019 Š U拳 W

||Om Shri Manjunathaya Namah || Shri Kshethra Dhamasthala Rural Development Project B.C. Trust ® Head Office Dharmasthala HŒ¯å A„®ãtÁS®¢Sµ, vw¯ºN® 22.12.2019 Š®0u®± w®lµu® îµ±°ªæX¯Š®N®/ N®Zµ°‹ š®œ¯‡®±N®/w®S®u®± š®œ¯‡®±N® œ®±uµÛ‡®± wµ°Š® wµ°î®±N¯r‡®± ªRq® y®‹°£µ‡®± y®ªq¯ºý® D Nµ¡®w®ºruµ. Cu®Š®ªå 50 î®±q®±Ù 50 Oʺq® œµX®±Ï AºN® y®lµu®î®Š®w®±Ý (¬šµ¶g¬w®ªå r¢›Š®±î®ºqµ N®Zµ°‹/w®S®u®± š®œ¯‡®±N® œ®±uµÛSµ N®xÇ®Õ ïu¯ãœ®Áqµ y®u®ï î®±q®±Ù ®±š®±é 01.12.2019 NµÊ Aw®æ‡®±î¯S®±î®ºqµ 25 î®Ç®Á ï±°Š®u®ºqµ î®±q®±Ù îµ±ªæX¯Š®N® œ®±uµÛSµ N®xÇ®Õ Hš¬.Hš¬.HŒ¬.› /z.‡®±±.› ïu¯ãœ®Áqµ‡µ²ºvSµ 3 î®Ç®Áu® Nµ©š®u® Aw®±„Â®î® î®±q®±Ù ®±š®±é 01.12.2019 NµÊ Aw®æ‡®±î¯S®±î®ºqµ 30 î®Ç®Á ï±°Š®u®ºqµ ) î®±±ºvw® œ®ºq®u® š®ºu®ý®Áw®NµÊ B‡µ±Ê ¯l®Œ¯S®±î®¼u®±. š®ºu®ý®Áw®u® š®Ú¡® î®±q®±Ù vw¯ºN®î®w®±Ý y®äqµã°N®î¯T Hš¬.Hº.Hš¬ î®±²©N® ¯Ÿr x°l®Œ¯S®±î®¼u®±. œ¯cŠ¯u® HŒ¯å A„®ãtÁS®¢Sµ A†Ãw®ºu®wµS®¡®±. Written test Sl No Name Address Taluk District mark Exam Centre out off 100 11 th ward near police station 1 A Ashwini Hospete Bellary 33 Bellary kampli 2 Abbana Durugappa Nanyapura HB hally Bellary 53 Bellary 'Sri Devi Krupa ' B.S.N.L 2nd 3 Abha Shrutee stage, Near RTO, Satyamangala, Hassan Hassan 42 Hassan Hassan. -

Jagalur Taluk, Davanangere District, Karnataka

Draft Report क� द्र�यभू�म �ल बो जल संसाधन, नद� �वकास और गंगा संर�ण मंत्रा भारत सरकार Central Ground Water Board Ministry of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation Government of India Report on AQUIFER MAPPING AND MANAGEMENT PLAN Jagalur Taluk, Davanangere District, Karnataka द��ण पि�चमी �ेत, ब�गलोर South Western Region,Bengaluru FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY No. Naquim-Taluk-15/2016-17 Government of India Ministry of Water Resources, River Development & Ganga Rejuvenation Central Ground Water Board JAGALUR TALUK AQUIFER MAPS AND MANAGEMENT PLAN DAVANAGERE DISTRICT, KARNATAKA STATE JAGALUR TALUK By Dr. A.Asokan Scientist ‘D’ Central Ground Water Board South Western Region Bangalore March 2017 JAGALUR TALUK AQUIFER MAPS AND MANAGEMENT PLANS, DAVANAGERE DISTRICT, KARNATAKA STATE CONTENTS Sl. No. Chapter Page No. Title 1 SALIENT INFORMATION 1 2 AQUIFER DISPOSITION 6 GROUND WATER RESOURCE, EXTRACTION, 9 3 CONTAMINATION AND OTHER ISSUES 4 GROUND WATER RESOURCE ENHANCEMENT 10 5 DEMAND SIDE INTERVENT IONS 12 JAGALUR TALUK AQUIFER MAPS AND MANAGEMENT PLAN, DAVANAGERE DISTRICT, KARNATAKA STATE 1. SALIENT INFORMATION Name of the taluk : JAGALUR District : Davanagere State : Karnataka Area : 978 sq.km. Populatio n: 1, 71,822 Annual Normal Rainfall : 546 mm 1.1 Aquifer management study area Aquifer mapping studies was carried out in Jagalur taluk, Davanagere district of Karnataka, covering an area of 978 sq.kms under National Aquifer Mapping Project. Jagalur taluk of Davanagere district is located between north latitude 14 024’18.5” and 14042’16.0” & east longitude 76006’34.7” and 76032’02.2”, and is covered in parts of Survey of India Toposheet Nos. -

Harapanahalli Bar Association : Harapanahalli Taluk : Harapanahalli District : Davanagere

3/17/2018 KARNATAKA STATE BAR COUNCIL, OLD KGID BUILDING, BENGALURU VOTER LIST POLING BOOTH/PLACE OF VOTING : HARAPANAHALLI BAR ASSOCIATION : HARAPANAHALLI TALUK : HARAPANAHALLI DISTRICT : DAVANAGERE SL.NO. NAME SIGNATURE HIREMATH VEERABHADRAIAH MYS/19/47 1 S/O CHANNABASAYYA ADVOCATE HARAPANA HALLI DAVANAGER HARAPANAHALLI DAVANAGERE VAIDYA NAGARAJACHAR MYS/48/55 2 S/O GOVINDACHAR MATADAKAVI BELLARI HARAPANAHALLI DAVANAGERE NINGAPPA A MYS/889/62 3 S/O MAHADEVAPPA A harapanahalli HARAPANAHALLI DAVANAGERE 583131 SIDDAPPA C MYS/57/73 4 S/O C KENCHAPPA D.NO. 371/2122 I ST WARD HARAPANAHALLI DAVANAGERE 583131 1/26 3/17/2018 BADANAHATTI KRISHNAMURTHY HANUMANTHARAO KAR/377/77 5 S/O BADANAHATTI HANUMANTHA RAO MATHDAKERI, HARAPANAHALLI DAVANAGERE 583131 AJJAPPA AJJI KARIYAPPA KAR/453/80 S/O BARAMAPPA AJJI KARIYAPPA 6 ARASIKERE POST, 1ST WARD, NEAR CHILUME ANJEYA TEMPLE HARAPANAHALLI DAVANAGERE 583131 VEERANNA G KAR/118/84 7 S/O G SAKRAGOUDA NO 707/2, 9tH WARD, NATARAJA BADAVANE HARAPANAHALLI DAVANAGERE 583131 PATEL SOMASHEKHARGOUD KARIBASANAGOUDA KAR/312/84 8 S/O PATEL KARIBASANAGOUDA PUNABAGATTI POST, HARAPANAHALLU BELLARI HARAPANAHALLI DAVANAGERE 583125 BYLUR SHAIKH VALI KAR/711/85 S/O BYLUR HUSSAIN SAB 9 K V R COLONY, HAGARI ,BOMMANAHALLI, BELLARI. HARAPANAHALLI DAVANAGERE 583212 2/26 3/17/2018 AJJANNA M KAR/807/85 10 S/O KOTRA BASAPPA M U HADAGALI ROAD , HARAPANAHALLY HARAPANAHALLI DAVANAGERE 583131 CHANDRA GOUD. K. KAR/630/86 11 S/O CHANDRESEKHARA GOUD C/O: DIWAKARA.K. ADV , DAVANGERI HARAPANAHALLI DAVANAGERE 583131 DEPUTY ABDUL RAHIMAN KAR/772/87 12 S/O YOUSUF SAB.D.M.D. NO.41, MASARAGERE, HARAPPANAHALLI HARAPANAHALLI DAVANAGERE 583 131 CHANDRA SHEKHAR BHAT.C. -

Dictionary of Martyrs: India's Freedom Struggle

DICTIONARY OF MARTYRS INDIA’S FREEDOM STRUGGLE (1857-1947) Vol. 5 Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu & Kerala ii Dictionary of Martyrs: India’s Freedom Struggle (1857-1947) Vol. 5 DICTIONARY OF MARTYRSMARTYRS INDIA’S FREEDOM STRUGGLE (1857-1947) Vol. 5 Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu & Kerala General Editor Arvind P. Jamkhedkar Chairman, ICHR Executive Editor Rajaneesh Kumar Shukla Member Secretary, ICHR Research Consultant Amit Kumar Gupta Research and Editorial Team Ashfaque Ali Md. Naushad Ali Md. Shakeeb Athar Muhammad Niyas A. Published by MINISTRY OF CULTURE, GOVERNMENT OF IDNIA AND INDIAN COUNCIL OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH iv Dictionary of Martyrs: India’s Freedom Struggle (1857-1947) Vol. 5 MINISTRY OF CULTURE, GOVERNMENT OF INDIA and INDIAN COUNCIL OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH First Edition 2018 Published by MINISTRY OF CULTURE Government of India and INDIAN COUNCIL OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH 35, Ferozeshah Road, New Delhi - 110 001 © ICHR & Ministry of Culture, GoI No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ISBN 978-81-938176-1-2 Printed in India by MANAK PUBLICATIONS PVT. LTD B-7, Saraswati Complex, Subhash Chowk, Laxmi Nagar, New Delhi 110092 INDIA Phone: 22453894, 22042529 [email protected] State Co-ordinators and their Researchers Andhra Pradesh & Telangana Karnataka (Co-ordinator) (Co-ordinator) V. Ramakrishna B. Surendra Rao S.K. Aruni Research Assistants Research Assistants V. Ramakrishna Reddy A.B. Vaggar I. Sudarshan Rao Ravindranath B.Venkataiah Tamil Nadu Kerala (Co-ordinator) (Co-ordinator) N. -

Typist Accepted and Rejected List .Pdf

LIST OF ELIGIBLE CANDIDATES FOR SKILL TEST FOR THE POST OF TYPIST VIDE NOTIFICATION NO.02/2017 DATED 31.05.2017 Register No. Application No. Name and address of the Candidates Date of Birth HEMA T w/o Sridhar.H 1 KOD1741TYP000003 07/06/1982 NO.88 EWS CITBUDAYAGIRI, MYSURU Taluka-MYSURU District- MYSURU PRATHIMA K P 2 KOD1741TYP000004 ARAMERI VILLAGE AND POSTVIRAJPET Taluka-VIRAJPET District- 11/08/1991 KODAGU KARIYAPPA G 3 KOD1741TYP000005 S/O GAVIRANGAPPANEAR BANASHANKARI TEMPLE Taluka- 25/09/1988 DAVANAGERE District-DAVANGERE SARASWATHI K 4 KOD1741TYP000006 JAYALAKSHMI TALKIES FRONT 4TH CROSS,MARUTHI NAGARA 27/05/1993 MADYA TOWN Taluka-MANDYA District-MANDYA SIDDHARTHA S VISHWAM 5 KOD1741TYP000007 D NO 55SATHEGALA HANDPOST KOLLEGAL Taluka-KOLLEGAL 15/06/1989 District-CHAMRAJNAGAR PUSHPA K S 6 KOD1741TYP000008 KAMPLAPURA VILLAGE AND POSTKAMPLAPURA Taluka- 20/06/1983 PIRIYAPATNA District-MYSURU RAVISHANKARA G R 7 KOD1741TYP000009 no. 329 NEAR TELEPHONE EXCHANGEMAIN ROAD GORUR Taluka- 20/05/1979 HASSAN District-HASSAN 573120 RAVISHANKARA G R KOD1741TYP000165 no. 329 NEAR TELEPHONE EXCHANGEMAIN ROAD GORUR 20/05/1979 HASSAN TALUK AND DIST Taluka-HASSAN District-HASSAN 573120 RAVISHANKARA G R KOD1741TYP000272 no. 329 NEAR TELEPHONE EXCHANGEGORUR Taluka-HASSAN 20/05/1979 District-HASSAN ANURAJ 8 KOD1741TYP000010 S/O NARAYANAPPA HNO 11-9-50 NEW BRESTAWAR PET 04/05/1989 UPPARWADIRAICHUR Taluka-RAICHUR District-RAICHUR LAXMI BAI D K 9 KOD1741TYP000012 1-11-1128/98 Ramanjineyya Colony Taluka-RAICHUR District- 15/06/1986 RAICHUR DHARMENDRA T 10 -

The Andhra State Act, 1953 Arrangement of Sections

THE ANDHRA STATE ACT, 1953 ______________ ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS _______________ PART I PRELIMINARY SECTIONS 1. Short title and commencement. 2. Definitions. PART II FORMATION OF ANDHRA STATE AND TRANSFER OF TERRITORY FROM MADRAS TO MYSORE 3. Formation of Andhra State. 4. Transfer of territory from Madras to Mysore. 5. Amendment of the First Schedule to the Constitution. PART III REPRESENTATION IN THE LEGISLATURES Council of states 6. Representation in the Council of States. 7. Amendment of the Fourth Schedule to the Constitution. 8. Allocation of sitting members. 9. Bye-election to fill vacancies. 10. Term of office. House of the People 11. Representation in the House of the People. 12. Delimitation of constituencies. 13. Provision as to sitting members. 14. Electoral rolls for modified Parliamentary constituencies Legislative Assemblies 15. Strength of Legislative Assemblies. 16. Allocation of members. 17. Duration of Legislative Assemblies. 18. Electoral rolls for modified Assembly constituencies. 1 SECTIONS 19. Madras Legislative Council. 20. Madras Council Constituencies. 21. Members of the Madras Legislative Council and their terms of office. 22. Mysore Legislative Council. 23. Electoral rolls for modified Council constituencies. MISCELLANEOUS 24. Revision of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Orders. 25. Rules of Procedure of the Andhra Legislative Assembly. 26. Amendment of section 2, Act 43 of 1950. 27. Amendment of section 9, Act 81 of 1952. PART IV HIGH COURTS 28. High Court for Andhra. 29. Judges of the Andhra High Court. 30. Jurisdiction of Andhra High Court. 31. Power to enrol advocates, etc. 32. Practice and procedure in Andhra High Court. 33. Custody of the Seal of the Andhra High Court. -

Determination of Groundwater Quality Index in Vidyanagar, Davanagere City, Karnataka State, India

ISSN: 2277-3754 ISO 9001:2008 Certified International Journal of Engineering and Innovative Technology (IJEIT) Volume 3, Issue 12, June 2014 Determination of Groundwater Quality Index in Vidyanagar, Davanagere City, Karnataka State, India Kalpana G R1, Nagarajappa D P2, Sham Sundar K M3, Suresh B4 1Post Graduate Student, Department of studies in Civil Engineering, University B.D.T. College of Engineering, Davanagere- 577004, Karnataka state, India 2Professor, Department of studies in Civil Engineering, University B.D.T. College of Engineering, Davanagere-577004, Karnataka state, India 3Professor, Department of studies in Civil Engineering, University B.D.T. College of Engineering, Davanagere-577004, Karnataka state, India 4Assistant Professor, Department of studies in Civil Engineering, Bapuji Institute of Engineering and Technology, Davanagere-577004, Karnataka state, India Abstract— Groundwater is natural resource for drinking water. water supply and irrigation all over the world. Rapid Due to human and industrial activities the ground water is urbanization, especially in developing countries like India, contaminated. This is the serious problem now a day. Thus the has affected the availability and quality of groundwater due to analysis of the water quality is very important to preserve and its overexploitation and improper waste disposal, especially prefect the natural eco system. The present work is aimed at 6 assessing the water quality index for the groundwater samples of in urban areas . According to WHO organization, about 80% Vidyanagar, Davanagere city. The groundwater samples of about of all the diseases in human beings are caused by water. Once 40 samples were collected and subjected for a comprehensive the groundwater is contaminated, its quality cannot be physicochemical analysis during the study period April 2014. -

Senior Civil Judge and JMFC, Harapanahalli SMT UNDI MANJULA SHIVAPPA SENIOR CIVIL JUDGE and JMFC Cause List Date: 19-12-2020

Senior Civil Judge and JMFC, Harapanahalli SMT UNDI MANJULA SHIVAPPA SENIOR CIVIL JUDGE AND JMFC Cause List Date: 19-12-2020 Sr. No. Case Number Timing/Next Date Party Name Advocate AFTERNOON SESSION 2:45 PM -5:00 PM 1 O.S. 160/2020 Satish Malpani G.C. GURUMATH (APPEARANCE OF Vs PARTIES/ADVOCATES-C) Sunil Malpani Call on 2 O.S. 165/2020 Shivasali @ Nekar Anandappa B.REVANAGOUD (APPEARANCE OF Vs PARTIES/ADVOCATES-C) Shivasali @ Nekar Gurubasappa 3 O.S. 166/2020 G M Sudha RAVI SHANKAR K.M. (APPEARANCE OF Vs PARTIES/ADVOCATES-C) U M Hemaiah 4 O.S. 167/2020 Wadra Hanumakka her PA B.REVANAGOUD (APPEARANCE OF holder of Wadra Parasappa PARTIES/ADVOCATES-C) Vs Wadra Muddamma @ Pakkiramma 5 O.S. 168/2020 Imam B K.Syed Khadar (APPEARANCE OF Vs PARTIES/ADVOCATES-C) Fathima SS TO DEFT. BY -SERVICE 6 O.S. 141/2020 ICICI Bank Ltd., R/by its G.S. Sannaveerappa (FIRST Authorized Officer, Manager HEARING/MAINTAINABILITY-C) Lokesh Shankar Patankar Vs Smt. Kesarabai @ Keeribayi 7 O.S. 142/2020 ICICI Bank Ltd., R/by its G.S. Sannaveerappa (FIRST Authorized Officer, Manager HEARING/MAINTAINABILITY-C) Lokesh Shankar Patankar Vs Kariyappa Putuganalu MORNING SESSION 10:00 AM -1:00 PM 8 O.S. 101/2015 Dundi siddappa SHANTHA MURTHY. (EVIDENCE-C) Vs N IA/1/2015 Smt.Mudla Gangamma 9 O.S. 102/2017 H.Prabhavathi P. JAGADISH GOWDA (APPEARANCE OF Vs PARTIES/ADVOCATES-C) Leelavathi 10 M.V.C. 438/2018 Smt. Manjamma (APPEARANCE OF Vs PARTIES/ADVOCATES-C) Ravi S 11 O.S. -

Census of India 2001 General Population Tables Karnataka

CENSUS OF INDIA 2001 GENERAL POPULATION TABLES KARNATAKA (Table A-1 to A-4) DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS KARNATAKA Data Product Number 29-019-2001-Cen.Book (E) (ii) CONTENTS Page Preface v Acknowledgement Vll Figure at a Glance ]X Map relating to Administrative Divisions Xl SECTION -1 General Note 3 Census Concepts and Definitions 11-16 SECTION -2 Table A-I NUMBER OF VILLAGES, TOWNS, HOUSEHOLDS, POPULATION AND AREA Note 18 Diagram regarding Area and percentage to total Area State & District 2001 19 Map relating to Rural and Urban Population by Sex 2001 20 Map relating to Sex ratio 2001 21 Diagram regarding Area, India and States 2001 22 Diagram regarding Population, India and States 2001 23 Diagram regarding Population, State and Districts 2001 24 Map relating to Density of Population 25 Statements 27-68 Fly-Leaf 69 Table A-I (Part-I) 70- 82 Table A-I (Part-II) 83 - 98 Appendix A-I 99 -103 Annexure to Appendix A-I 104 Table A-2 : DECADAL VARIATION IN POPULATION SINCE 1901 Note 105 Statements 106 - 112 Fly-Leaf 113 Table A-2 114 - 120 Appendix A-2 121 - 122 Table A-3 : VILLAGES BY POPULATION SIZE CLASS Note 123 Statements 124 - 128 Fly-Leaf 129 Table A-3 130 - 149 Appendix A-3 150 - 154 (iii) Page Table A-4 TOWNS AND URBAN AGGLOMERATIONS CLASSIFIED BY POPULATION SIZE CLASS IN 2001 WITH VARIATION SINCE 1901 Note 155-156 Diagram regarding Growth of Urban Population showing percentage (1901-2001) 157- 158 Map showing Population of Towns in six size classes 2001 159 Map showing Urban Agglomerations 160 Statements 161-211 Alphabetical list of towns. -

Office of Senior Geologist Dept., of Mines and Geology Davangere

Office of Senior Geologist Dept., of Mines and Geology Davangere. Right to information act 2005 Rule 4(1)A Page 1 Part-I Right to information act 2005 Rule 4(1)A details Right to information act 2005 INDEX As per Rule 4(1)A details Sl Details Page No. No. 1 Establishment Section 4 to 7 2 Cash Section 7 to 9 3 Computer Section 9 4 Drawing Section 9 5 Mining Lease Section 09 to 12 6 Quarry Lease Section 12 to 40 7 Quarry LeaseApplication 40 to 47 8 Court Files 47 to 49 9 Stone Crusher Section 49 to 57 10 Crusher Form-C Issed File Details 58 to 67 11 Ordinary Sand 68 to 69 e-tender cum-action issued lease file 12 70 to 71 details Crusher Permit File List 13 14 DMG Releated files Page 2 Details of file index in office as per Right to information act 2005 Rule 4(1)A Administration Section Establishment Section Sl Opening Closing Rem File No. File Details No Date Date arks Sri. H.P. Mallesh 1 Sg/dmg/est/01/2009-10 Senior Geologist 11-04-2009 Personnel File Sri Pradeep S 2 Sg/dmg/est/02/2009-10 Geologist 25-09-2009 Personnel File Sg/dmg/est/03/2009-10 Smt. Rekha 3 F.D.A (Deputation) 14-10-2009 Personnel File Sg/dmg/est/04/2009-10 Sri R.J. Vijay Vikram 4 Geologist (Deputation) 20-10-2009 Personnel File Sg/dmg/est/05/2009-10 Sri K.S. Ravi 5 Driver 29-09-2009 (Deputation) Personnel File Sg/dmg/est/06/2009-10 Sri Prashanth Kumar 6 Driver 10-02-2009 (Deputation) Personnel File Sg/dmg/est/07/2009-10 C. -

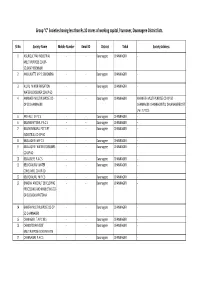

Davanagere District Lists

Group "C" Societies having less than Rs.10 crores of working capital / turnover, Davanagere District lists. Sl No Society Name Mobile Number Email ID District Taluk Society Address 1 AGURICULTRAL INDUSTRIAL - - Davanagere CHANNAGIRI - MULTI PURPOSE CO-OP- SO,SANTHEBENNUR 2 AKKALIKATTE M P C S(WOMEN) - - Davanagere CHANNAGIRI - 3 ALURU MINOR IRRIGATION - - Davanagere CHANNAGIRI - WATER CONSUMER CO-OP-SO 4 AMANATH MULTI PURPOSE CO - - - Davanagere CHANNAGIRI AMANATH MULTI PURPOSE CO-OP SO OP SO CHANNAGIRI CHANNAGIRI CHANNAGIRI TQ DAVANAGERE DIST ,Pin : 577213 5 AREHALLI M P C S - - Davanagere CHANNAGIRI - 6 BASAVAPATTANA P A C S - - Davanagere CHANNAGIRI - 7 BASAVESHWARA POTTERY - - Davanagere CHANNAGIRI - INDUSTRIAL CO-OP-SO 8 BELALAGERE M P C S - - Davanagere CHANNAGIRI - 9 BELALAGERE WATER CONSUMRS - - Davanagere CHANNAGIRI - CO-OP-SO 10 BELALIGERE P A C S - - Davanagere CHANNAGIRI - 11 BELLIGANUDU WATER - - Davanagere CHANNAGIRI - CONSUMRS CO-OP-SO 12 BELLIGANURU M P C S - - Davanagere CHANNAGIRI - 13 BHADRA ARCONUT DEVELOPING - - Davanagere CHANNAGIRI - PROCESSING AND MARKETING CO- OP-SO BASAVAPATTANA 14 BHADRA MULTI PURPOSE CO-OP - - Davanagere CHANNAGIRI - SO CHANNAGIRI 15 CHANAGIRI T A P C M S - - Davanagere CHANNAGIRI - 16 CHANDRODAYA SSST - - Davanagere CHANNAGIRI - MULTIPURPOSE SO KEREKATTE 17 CHANNAGIRI P A C S - - Davanagere CHANNAGIRI - 18 CHANNAGIRI TALUK PRIMERY - - Davanagere CHANNAGIRI - SCHOOL TEACHERS CREDIT CO-OP- SO 19 CHIKKA GANGURU M P C S - - Davanagere CHANNAGIRI - 20 CHIKKA GANGURU P A C S - - Davanagere CHANNAGIRI