National Curriculum Reform: Key Stage 4 Core Subjects Consultation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Key Stage 4 Performance, 2019 (Revised)

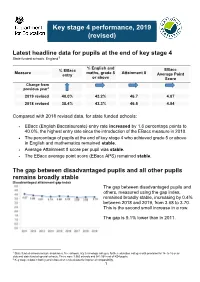

Key stage 4 performance, 2019 (revised) Latest headline data for pupils at the end of key stage 4 State funded schools, England1 % English and % EBacc EBacc Measure maths, grade 5 Attainment 8 entry Average Point or above Score Change from 2 previous year 2019 revised 40.0% 43.2% 46.7 4.07 2018 revised 38.4% 43.3% 46.5 4.04 Compared with 2018 revised data, for state funded schools: • EBacc (English Baccalaureate) entry rate increased by 1.6 percentage points to 40.0%, the highest entry rate since the introduction of the EBacc measure in 2010. • The percentage of pupils at the end of key stage 4 who achieved grade 5 or above in English and mathematics remained stable. • Average Attainment 8 score per pupil was stable. • The EBacc average point score (EBacc APS) remained stable. The gap between disadvantaged pupils and all other pupils remains broadly stable Disadvantaged attainment gap index The gap between disadvantaged pupils and others, measured using the gap index, remained broadly stable, increasing by 0.4% between 2018 and 2019, from 3.68 to 3.70. This is the second small increase in a row. The gap is 9.1% lower than in 2011. 1 State funded schools include academies, free schools, city technology colleges, further education colleges with provision for 14- to 16-year- olds and state-funded special schools. There were 3,965 schools and 542,568 end of KS4 pupils. 2 Key stage 4 data in both years is based on revised data for improved comparability. 1 About this release This release summarises exam entry and achievements of pupils at the end of key stage 43 (KS4) in 2019. -

RE: Statutory Requirements, Compliance and OFSTED

RE: Statutory requirements, compliance and OFSTED Statutory requirements and curriculum information The national curriculum states the legal requirement that: 'Every state-funded school must offer a curriculum which is balanced and broadly based, and which: • promotes the spiritual, moral, cultural, mental and physical development of pupils; and • prepares pupils at the school for the opportunities, responsibilities and experiences of later life. All state schools ... must teach religious education ... All schools must publish their curriculum by subject and academic year online'. (National Curriculum in England: Framework Document, DfE, September 2013, p.4) Although there is not a National Curriculum for RE, all maintained schools must follow the National Curriculum requirements to teach a broad and balanced curriculum, which includes RE. All maintained schools therefore have a statutory duty to teach RE. Academies and free schools are contractually required through the terms of their funding agreement to make provision for the teaching of RE. Further information concerning RE in academies and free schools is given below. The RE curriculum is determined by the local Standing Advisory Council on Religious Education (SACRE), which is responsible for producing the locally agreed syllabus for RE. Agreed Syllabuses used in schools (maintained or academy), which are not designated with a religious character must ‘reflect the fact that the religious traditions in Great Britain are in the main Christian, while taking account of the teaching and practices of the other principal religions represented in Great Britain’. Schools with a religious designation may prioritise one religion in their RE curriculum, but all schools must recognise diverse religions and systems of belief in the UK both locally and nationally. -

The Sciences at Key Stage 4: Time for a Re-Think? Why Key Stage 4 Is So Important, and Why Changes Are Needed

The sciences at key stage 4: time for a re-think? Why key stage 4 is so important, and why changes are needed Key stage 4 is a pivotal period of time in a student’s chemistry and biology are currently the preserve of school life; it is the point at which they make subject a minority. There is evidence that the existence of choices that define their future study, as well as their multiple routes through key stage 4 disadvantages a last experience of those subjects that they do not large number of students in both their experiences and choose to take further. The sciences are core subjects the choices that are taken away from them. For this to 16, yet multiple qualifications exist for students reason, the SCORE organisations are proposing that of this age. As this discussion paper documents, there should be a single route in the sciences for all evidence suggests that rich opportunities in physics, students up to the age of 16. SCORE’sSCORE’s proposal: proposal: a asingle single route route in in the the sciences sciences SCORE’sSCORE’s vision vision is thatis that opportunities opportunities for forhigh-quality high-quality studyexciting of the sciences and inspiring are available experience to all, of onthe an sciences, studyequitable of the sciencesbasis, and are we available believe thatto all, this on can an only be achievedproviding by the them creation with ofthe a skillssingle and route knowledge at key to equitablestage 4. basis, This singleand we route believe would that remove this can the only need for decisionssucceed to be in madetheir future at 14 endeavours,that could limit whether students’ or not be futureachieved choices, by the and creation give all of students a single routean authentic, at key excitingthey and decideinspiring to experience pursue the ofsciences the sciences, beyond 16. -

Terms for School Levels This Table Features Education Terms Used in Canada, the U.S., the U.K., and Other Countries

Terms for School Levels This table features education terms used in Canada, the U.S., the U.K., and other countries. This includes reference to the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) maintained by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). This table provides a general sense of school terminology and age ranges, as there are differences within each country or sovereign country. In those respects, Quebec differs slightly from British Columbia, Scotland differs slightly from England, etc. This table is one of the eResources from the book Sharing Your Education Expertise with the World: Make Research Resonate and Widen Your Impact by Jenny Grant Rankin, Ph.D. See the book for terminology explanations and more. Age Canadian Terms US Terms UK Terms UNESCO ISCED Terms early junior kindergarten, early preschool, nursery school Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS)ante-pre-school, early childhood early childhood ≤ 4 childhood pre-kinder., preschool education primary nursery childminders, education, educational education kindergarten, primary stage infant, key stage 1 children's Level 0 development, pre- 5 K-12 primary elementary school centre, nursery Level 1 primary education classes/school, elementary grades 1-8 (in (kindergarten school (starts with grade TK or 6 pre-school, education Quebec, grade through K and ends after 6th primary school, school and the first grade 12) or grade around age 11 if or reception 7 half of high school) TK-12 student goes on to (transitional middle school; -

Social Selectivity of State Schools and the Impact of Grammars

_____________________________________________________________________________ Social selectivity of state schools and the impact of grammars A summary and discussion of findings from ‘Evidence on the effects of selective educational systems’ by the Centre for Evaluation and Monitoring at Durham University The Sutton Trust, October 2008 Contents Executive summary 3 Introduction and background 5 Findings -- selectivity 7 Findings – pupil intakes 10 Findings – attainment 12 Discussion 13 Proposed ways forward 16 Appendix 18 2 Executive summary Overview This study shows that the vast majority of England's most socially selective state secondary schools are non-grammar schools. However, England's remaining grammar schools are enrolling half as many academically able children from disadvantaged backgrounds as they could do. The research also concludes that the impact on the academic results of non-grammar state schools due to the ‘creaming off’ of pupils to grammar schools is negligible. Grammars have a widespread, low-level, impact on pupil enrolments across the sector. A relatively small number of non-selective schools do see a significant proportion of pupils ‘lost’ to nearby grammars, but this does not lead to lower academic achievement. The Trust proposes that a further study be undertaken to review ‘eleven plus’ selection tests to see whether they deter bright pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds applying to grammar schools, and urges more grammars to develop outreach schemes to raise the aspirations and achievement of children during primary school. It also backs calls for religious schools to consider straightforward 'binary' criteria to decide which pupils should be admitted on faith grounds, and other ways – including the use of banding and ballots – to help make admissions to all secondary state schools operate more equitably. -

Secondary and Post-Secondary Non-Tertiary Education

Published on Eurydice (https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice) This chapter covers the organisation and structure of educational provision for young people aged 11 to 18/19 years. For the purpose of this description, this provision is divided into: general lower secondary education [1] (for ages 11–16) general upper secondary education [2] (for ages 16–18/19) vocational upper secondary education [3] (for ages 16–18/19).* * In terms of International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) [4] categorisation, education for ages 11-14, is classified as ISCED 2; education for ages 14-18/19 as ISCED 3. There are no programmes categorised as post-secondary non-tertiary education (ISCED 4). For 16- to 18/19-year olds, there is a well-established tradition of subject specialisation, with the possibility of combining single subject general and vocational qualifications. More recently, the Government has introduced a policy on study programmes that applies across general and vocational education. For these reasons, the introduction to this chapter provides a combined description of general and vocational upper secondary education. General lower secondary education, ages 11-16 Young people enter secondary education at the age of 11 and, under Section 8 of the Education Act 1996 [5], full-time education is then compulsory up until the last Friday in June of the school year in which they reach the age of 16. Secondary schools cater for pupils from age 11 to either 16 or to 18/19. Study programmes Lower secondary education is divided into two key stages of the national curriculum [6]: Key Stage 3 - for pupils aged 11 to 14, ISCED 2 Key Stage 4 - for pupils aged 14 to 16, ISCED 3. -

The National Curriculum in England Key Stages 1 and 2 Framework Document

The national curriculum in England Key stages 1 and 2 framework document September 2013 Contents 1. Introduction 4 2. The school curriculum in England 5 3. The national curriculum in England 6 4. Inclusion 8 5. Numeracy and mathematics 9 6. Language and literacy 10 7. Programmes of study and attainment targets 12 English 13 Spoken language – years 1 to 6 17 Key stage 1 – year 1 19 Key stage 1 – year 2 26 Lower key stage 2 – years 3 and 4 33 Upper key stage 2 – years 5 and 6 41 English Appendix 1: Spelling 49 Spelling – work for year 1 50 Spelling – work for year 2 55 Spelling – work for years 3 and 4 59 Word list – years 3 and 4 64 Spelling – years 5 and 6 66 Word list – years 5 and 6 71 International Phonetic Alphabet (non-statutory) 73 English Appendix 2: Vocabulary, grammar and punctuation 74 Glossary for the programmes of study for English (non-statutory) 80 Mathematics 99 Key stage 1 – years 1 and 2 101 Year 1 programme of study 102 Year 2 programme of study 107 Lower key stage 2 – years 3 and 4 113 Year 3 programme of study 114 Year 4 programme of study 120 2 Upper key stage 2 – years 5 and 6 126 Year 5 programme of study 127 Year 6 programme of study 135 Mathematics Appendix 1: Examples of formal written methods for addition, subtraction, multiplication and division 142 Science 144 Key stage 1 146 Key stage 1 programme of study – years 1 and 2 147 Year 1 programme of study 148 Year 2 programme of study 151 Lower key stage 2 – years 3 and 4 154 Lower key stage 2 programme of study 155 Year 3 programme of study 157 Year 4 programme of study 161 Upper key stage 2 – years 5 and 6 165 Upper key stage 2 programme of study 166 Year 5 programme of study 168 Year 6 programme of study 172 Art and design 176 Computing 178 Design and technology 180 Geography 184 History 188 Languages 193 Music 196 Physical education 198 3 1. -

Transition from Key Stage 3 to Key Stage 4

KS3/4KS5 Transition from Key Stage 3 to Key Stage 4 John Kelleher by John Kelleher is a freelance education consultant specialising in For any school teacher, the word ‘transition’ instantly conjures up an image of 11-year-olds looking anxious music and music about their first days of secondary school. This time-honoured rite of passage is, quite correctly, assigned a technology. He provides advice, high priority by schools so as to ensure that the move from Key Stage 2 to Key Stage 3 is as smooth as possible, training and and that natural anxieties are at least mixed in with a healthy dose of excitement about new challenges. resources for music teachers. There is, however, another transition that has a significant impact on our pupils: the move from Key Stage Before moving into consultancy work, 3 to Key Stage 4. With the vast majority of pupils staying in the same school, it’s easy for us to overlook the John was part of the difficulties that teenagers face during these tumultuous few months. At the very least, it’s tempting to see it as a senior leadership problem for the head of year and his/her team of form tutors who invariably deal with the fallout of young people team and director of music at a London suddenly having to cope with a set of examinations that have the potential to determine the path they take for secondary school. the rest of their lives. While the humble music teacher cannot resolve all the issues, there’s a lot we can do to minimise the stress caused by KS3-4 transition in our subject area, and even to make our music departments feel like a ‘safe zone’ during the process. -

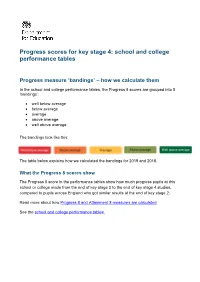

Progress Scores for Key Stage 4: School and College Performance Tables

Progress scores for key stage 4: school and college performance tables Progress measure ‘bandings’ – how we calculate them In the school and college performance tables, the Progress 8 scores are grouped into 5 ‘bandings’: • well below average • below average • average • above average • well above average The bandings look like this: The table below explains how we calculated the bandings for 2019 and 2018. What the Progress 8 scores show The Progress 8 score in the performance tables show how much progress pupils at this school or college made from the end of key stage 2 to the end of key stage 4 studies, compared to pupils across England who got similar results at the end of key stage 2. Read more about how Progress 8 and Attainment 8 measures are calculated See the school and college performance tables. How we calculated the bandings for 2019 and 2018 Progress A school/college1 was given the description if… description The progress score is 0.5 or higher, and lower confidence interval limit Well above is higher than 0. average 2019: About 14% of schools/colleges in England 2018: About 14% of schools/colleges in England The progress score is higher than 0 but lower than 0.5, and lower confidence interval limit is higher than 0. Above average 2019: About 17% of schools/colleges in England 2018: About 17% of schools/colleges in England The progress score has a confidence interval that includes 0. That is, the score’s lower confidence interval limit is 0 or less and/or the Average score’s upper confidence interval limit is 0 or more. -

Tbsc Student

OUR SCHOOL The British School Caracas was founded in 1950 and has been on its current site in Altamira since 1954. From its earliest days, when the student body was comprised of 37 students it has developed into one of the foremost British Schools in Latin America providing a high quality British education to the national and international community. With the curriculum combining the framework and high standards of the English National Curriculum with the diversity of Venezuelan culture and Spanish language, the educational experience enjoyed by the students is without parallel. 1 VISION The British School Caracas will provide an outstanding international education, which will enable all students to attain their potential. Our students will be inspired to become lifelong learners who contribute actively and positively to the global community. MISSION The British School Caracas provides a world class British and international programme for students aged 3 to 18 within a caring, family environment. We encourage our students to aspire to become productive members and leaders in a dynamic and evolving world. They will develop diverse and transferable skills and attributes to fulfil their academic, emotional, creative and physical potential. The school community fosters attitudes that promote intercultural understanding and sustainable practices. 2 TBSC TEACHER TBSC is committed to a contemporary student-centred approach to teaching for which staff receive significant professional development. Our staff have significant England National Curriculum experience and are recruited from the UK, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, USA, France and Venezuela. A R AC A S C CHOOL S RITISH B HE T 3 TBSC STUDENT At TBSC we recognise that the demands of the 21st century require an approach to education that not only fully prepares students for college but also for an ever-changing, more globally connected world. -

The Key Stage 4 Curriculum Increased Flexibility and Work-Related Learning

The Key Stage 4 curriculum Increased flexibility and work-related learning Schools have been able to take advantage of flexibility in the curriculum to adapt the range of subjects to better meet students’ needs. At the same time, work-related learning has been a statutory requirement. The second year of this survey reports on how well schools and colleges are responding to change. Age group: 14 to 19 Published: May 2007 Reference no: 070113 This document may be reproduced in whole or in part for non-commercial educational purposes, provided that the information quoted is reproduced without adaptation and the source and date of publication are stated. Alexandra House 33 Kingsway London WC2B 6SE T 08456 404040 www.ofsted.gov.uk Published May 2007 Reference no. 070113 © Crown Copyright 2007 Contents Executive summary 4 Key findings 5 Recommendations 6 The context 7 The impact of curriculum change 7 Achievement 8 Attendance and attitudes to learning 9 Students’ views 9 Learning about work 9 Learning for work 10 Learning through work 10 Factors contributing to impact 11 Match of curriculum to need 11 Work-related learning 15 Work experience 16 Quality of teaching 17 Guidance and support 20 Leadership and management 21 Resources and staff development 22 Resources 22 Staff training and development 22 Strategic planning to implement change 23 Collaboration and partnership 23 Local prospectuses 25 Notes 26 Further information 27 Publications by Ofsted 27 Relevant websites 28 Annex 29 Schools and colleges visited for this survey 29 Executive summary Since September 2004, in addition to core subjects, schools have been required to provide work-related and enterprise learning for all students at Key Stage 4, as well as an entitlement for them to study the arts, design and technology, humanities and modern foreign languages, should they so wish. -

The Result of 11+ Selection: an Investigation Into Opportunities and Outcomes for Pupils in Selective Leas Adele Atkinson, Paul

THE CENTRE FOR MARKET AND PUBLIC ORGANISATION The Centre for Market and Public Organisation (CMPO) is a leading research centre, combining expertise in economics, geography and law. Our objective is to study the intersection between the public and private sectors of the economy, and in particular to understand the right way to organise and deliver public services. The Centre aims to develop research, contribute to the public debate and inform policy-making. CMPO, now an ESRC Research Centre was established in 1998 with two large grants from The Leverhulme Trust. In 2004 we were awarded ESRC Research Centre status, and CMPO now combines core funding from both the ESRC and the Trust. Centre for Market and Public Organisation Bristol Institute of Public Affairs University of Bristol 2 Priory Road Bristol BS8 1TX Tel: (0117) 33 10799 Fax: (0117) 33 10705 E-mail: [email protected] The result of 11+ Selection: An Investigation into Opportunities and Outcomes for Pupils in Selective LEAs Adele Atkinson, Paul Gregg and Brendon McConnell April 2006 Working Paper No. 06/150 ISSN 1473-625X CMPO Working Paper Series No. 06/150 The Result of 11 Plus Selection: An Investigation into Opportunities and Outcomes for Pupils in Selective LEAs Adele Atkinson1 2 Paul Gregg and Brendon McConnell2 1Personal Finance Research Centre, University of Bristol 2 CMPO, University of Bristol April 2006 Abstract This paper assesses the impact of academic selection at age 11 on children in the minority of areas that still operate such a system. The answers are very clear. Overall there is little or no impact on attainment, but those educated in grammar schools do substantially better (around four grade points more than pupils with the same Key Stage 2 (KS2) points in similar, but non-selective, areas).