The Key Stage 4 Curriculum Increased Flexibility and Work-Related Learning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TYPE Aylesbury Grammar School Further Offers Ma

Moving up to Secondary School in September 2014 Second Round Allocation Positions GRAMMAR SCHOOLS GRAMMAR SCHOOLS - ALLOCATION PROFILE (qualified applicants only) TYPE Further offers made under rule 4 (linked siblings), and some under rule 7 (catchment) to a distance of 1.291 Aylesbury Grammar School Academy miles. Aylesbury High School All applicants offered. Academy Beaconsfield High School All applicants offered. Foundation Burnham Grammar School Further offers made under rule 5 (distance) to 10.456 miles. Academy Chesham Grammar School All applicants offered. Academy Dr Challoner's Grammar School Further offers made under rule 4 (catchment) to a distance of 7.378 miles. Academy Dr Challoner's High School Further offers made under rule 2 (catchment) to a distance of 6.330 miles. Academy John Hampden Grammar School All applicants offered. Academy The Royal Grammar School Further offers made under rule 2 (catchment) and some under rule 6 (distance) to 8.276 miles. Academy The Royal Latin School Further offers made under rule 2 (catchment) some under rule 5 (distance) to 7.661 miles. Academy Sir Henry Floyd Grammar School All applicants offered. Academy Further offers made under rule 2{3}(catchment siblings) and some under rule 2 (catchment), to a distance of Sir William Borlase's Grammar School Academy 0.622 miles. Wycombe High School Further offers made under rule b (catchment) and some under rule d (distance) to 16.957 miles. Academy UPPER SCHOOLS UPPER SCHOOLS - ALLOCATION PROFILE TYPE Further offers made under rule b (catchment), rule c (siblings) and some under rule e (distance) to 4.038 Amersham School Academy miles. -

Bus Franchising Scheme and Notice

Public Document BUS FRANCHISING SCHEME & NOTICE – 30 March 2021 This page is intentionally left blank Agenda Item 1 TRANSPORT ACT 2000 The Greater Manchester Franchising Scheme for Buses 2021 Made 30/03/2021 ARRANGEMENT OF THE SCHEME 1. CITATION AND COMMENCEMENT…………………………………………………………………………………1 2. INTERPRETATION………………………………………………………………………………………………….……...1 3. THE FRANCHISING SCHEME AREA AND SUB-AREAS………………………………………………….…..2 4. ENTRY INTO LOCAL SERVICE CONTRACTS……………………………………………………………………..2 5. SERVICES UNDER LOCAL SERVICE CONTRACTS………………………………………………….………….3 6. EXCEPTIONS FROM THE SCHEME……………………………………………………………………….………..3 7. SCHEME FACILITIES………………………………………………………………………………………………….…..3 8. PLAN FOR CONSULTING ON OPERATION OF THE SCHEME……………………………………………4 ANNEXES TO THE SCHEME………………………………………………………………………………………………………..5 ANNEX 1: SERVICES INCLUDED – ARTICLE 5…………………………………………………………………….………..5 ANNEX 2: SERVICES INCLUDED – ARTICLE 5.2.3………………………………………………………………………..11 ANNEX 3: EXCEPTED SERVICES – ARTICLE 6………………………………………………………………………………14 ANNEX 4: TEMPORARY EXCEPTIONS – ANNEX 3 PARAGRAPHS 1.2 AND 1.3……………………………..15 ANNEX 5: FRANCHISING SCHEME SUB-AREAS…………………………………………………………………………..18 Page 1 WHEREAS: A The Transport Act 2000 (as amended) ("2000 Act") makes provision for a franchising authority to make a franchising scheme covering the whole or any part of its area. The GMCA is a franchising authority as defined in the 2000 Act. B The GMCA gave notice of its intention to prepare an assessment of a proposed scheme in accordance with sections 123B and section 123C(4) of the 2000 Act on 30 June 2017. Having complied with the process as set out in the Act, the GMCA may determine to make the scheme in accordance with sections 123G and 123H of the 2000 Act. NOW, therefore, the Mayor on behalf of the GMCA, in exercise of the powers conferred by sections 123G and 123H of the 2000 Act, and of all other enabling powers, hereby MAKES THE FOLLOWING FRANCHISING SCHEME (the "Scheme"): 1. -

Press Release

press release 3 July 2009 The Grange School win South East region of Shares4Schools The Grange School made a 84.1% profit in just eight months The team of four Year 12 students outperformed the FTSE 100 by 87.3% Vale schools invited to apply for funding for 2009/10 competition A group of four Year 12 students at The Grange School, Aylesbury has beaten 13 schools to become the South East regional winners of Shares4Schools, a national investment competition run by retail stockbroker, The Share Centre. The team also came second in the national league by making an exceptional £1,262.07 profit in just eight months, despite stock market volatility. The group turned their initial investment of £1,500 at the start of October 2008 into an 84.1% profit, leaving them with £2,762.07 when the competition closed on the 5 June 2009. The same amount invested in tracking the FTSE 100 would have returned a loss of 3.2%. Commenting on the team’s success, Gavin Oldham, chief executive of The Share Centre said: “Students participating in this year’s competition have faced some of the toughest trading conditions since Shares4Schools started back in 2003. Despite this, The Grange School rose to the challenge to achieve an amazing capital gain. I am sure the students will take this knowledge forward and capitalise on it in whatever career they choose.” Commenting on the team’s investment experience, Jess Smith, a member of the successful team said: “We are thrilled to have beaten all the other schools in the South East. -

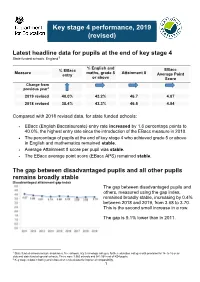

Key Stage 4 Performance, 2019 (Revised)

Key stage 4 performance, 2019 (revised) Latest headline data for pupils at the end of key stage 4 State funded schools, England1 % English and % EBacc EBacc Measure maths, grade 5 Attainment 8 entry Average Point or above Score Change from 2 previous year 2019 revised 40.0% 43.2% 46.7 4.07 2018 revised 38.4% 43.3% 46.5 4.04 Compared with 2018 revised data, for state funded schools: • EBacc (English Baccalaureate) entry rate increased by 1.6 percentage points to 40.0%, the highest entry rate since the introduction of the EBacc measure in 2010. • The percentage of pupils at the end of key stage 4 who achieved grade 5 or above in English and mathematics remained stable. • Average Attainment 8 score per pupil was stable. • The EBacc average point score (EBacc APS) remained stable. The gap between disadvantaged pupils and all other pupils remains broadly stable Disadvantaged attainment gap index The gap between disadvantaged pupils and others, measured using the gap index, remained broadly stable, increasing by 0.4% between 2018 and 2019, from 3.68 to 3.70. This is the second small increase in a row. The gap is 9.1% lower than in 2011. 1 State funded schools include academies, free schools, city technology colleges, further education colleges with provision for 14- to 16-year- olds and state-funded special schools. There were 3,965 schools and 542,568 end of KS4 pupils. 2 Key stage 4 data in both years is based on revised data for improved comparability. 1 About this release This release summarises exam entry and achievements of pupils at the end of key stage 43 (KS4) in 2019. -

RE: Statutory Requirements, Compliance and OFSTED

RE: Statutory requirements, compliance and OFSTED Statutory requirements and curriculum information The national curriculum states the legal requirement that: 'Every state-funded school must offer a curriculum which is balanced and broadly based, and which: • promotes the spiritual, moral, cultural, mental and physical development of pupils; and • prepares pupils at the school for the opportunities, responsibilities and experiences of later life. All state schools ... must teach religious education ... All schools must publish their curriculum by subject and academic year online'. (National Curriculum in England: Framework Document, DfE, September 2013, p.4) Although there is not a National Curriculum for RE, all maintained schools must follow the National Curriculum requirements to teach a broad and balanced curriculum, which includes RE. All maintained schools therefore have a statutory duty to teach RE. Academies and free schools are contractually required through the terms of their funding agreement to make provision for the teaching of RE. Further information concerning RE in academies and free schools is given below. The RE curriculum is determined by the local Standing Advisory Council on Religious Education (SACRE), which is responsible for producing the locally agreed syllabus for RE. Agreed Syllabuses used in schools (maintained or academy), which are not designated with a religious character must ‘reflect the fact that the religious traditions in Great Britain are in the main Christian, while taking account of the teaching and practices of the other principal religions represented in Great Britain’. Schools with a religious designation may prioritise one religion in their RE curriculum, but all schools must recognise diverse religions and systems of belief in the UK both locally and nationally. -

Proposed Free School – Opening September 2018 Report on Section 10 Public Consultation 9Th June 2017-8Th September 2017

Laurus Ryecroft Proposed free school – opening September 2018 Report on Section 10 public consultation th th 9 June 2017-8 September 2017 laurustrust.co.uk 4 October 17 Page 1 of 21 Contents Executive summary ............................................................................................................... 3 The proposer group ............................................................................................................... 4 Initial phase ........................................................................................................................... 4 Statutory consultation ............................................................................................................ 6 Stakeholders ......................................................................................................................... 7 Statutory consultation results and responses ........................................................................ 9 Other responses to the consultation .................................................................................... 18 Conclusion and next steps .................................................................................................. 21 Appendices: Appendix 1 – Section 10 consultation information booklet Appendix 2 – Consultation questionnaire Appendix 3 – Promotional material Appendix 4 – Stakeholders laurustrust.co.uk 4 October 17 Page 2 of 21 Executive summary Laurus Ryecroft is a non-selective, non-denominational 11-18 secondary school in the pre-opening -

The Sciences at Key Stage 4: Time for a Re-Think? Why Key Stage 4 Is So Important, and Why Changes Are Needed

The sciences at key stage 4: time for a re-think? Why key stage 4 is so important, and why changes are needed Key stage 4 is a pivotal period of time in a student’s chemistry and biology are currently the preserve of school life; it is the point at which they make subject a minority. There is evidence that the existence of choices that define their future study, as well as their multiple routes through key stage 4 disadvantages a last experience of those subjects that they do not large number of students in both their experiences and choose to take further. The sciences are core subjects the choices that are taken away from them. For this to 16, yet multiple qualifications exist for students reason, the SCORE organisations are proposing that of this age. As this discussion paper documents, there should be a single route in the sciences for all evidence suggests that rich opportunities in physics, students up to the age of 16. SCORE’sSCORE’s proposal: proposal: a asingle single route route in in the the sciences sciences SCORE’sSCORE’s vision vision is thatis that opportunities opportunities for forhigh-quality high-quality studyexciting of the sciences and inspiring are available experience to all, of onthe an sciences, studyequitable of the sciencesbasis, and are we available believe thatto all, this on can an only be achievedproviding by the them creation with ofthe a skillssingle and route knowledge at key to equitablestage 4. basis, This singleand we route believe would that remove this can the only need for decisionssucceed to be in madetheir future at 14 endeavours,that could limit whether students’ or not be futureachieved choices, by the and creation give all of students a single routean authentic, at key excitingthey and decideinspiring to experience pursue the ofsciences the sciences, beyond 16. -

Terms for School Levels This Table Features Education Terms Used in Canada, the U.S., the U.K., and Other Countries

Terms for School Levels This table features education terms used in Canada, the U.S., the U.K., and other countries. This includes reference to the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) maintained by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). This table provides a general sense of school terminology and age ranges, as there are differences within each country or sovereign country. In those respects, Quebec differs slightly from British Columbia, Scotland differs slightly from England, etc. This table is one of the eResources from the book Sharing Your Education Expertise with the World: Make Research Resonate and Widen Your Impact by Jenny Grant Rankin, Ph.D. See the book for terminology explanations and more. Age Canadian Terms US Terms UK Terms UNESCO ISCED Terms early junior kindergarten, early preschool, nursery school Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS)ante-pre-school, early childhood early childhood ≤ 4 childhood pre-kinder., preschool education primary nursery childminders, education, educational education kindergarten, primary stage infant, key stage 1 children's Level 0 development, pre- 5 K-12 primary elementary school centre, nursery Level 1 primary education classes/school, elementary grades 1-8 (in (kindergarten school (starts with grade TK or 6 pre-school, education Quebec, grade through K and ends after 6th primary school, school and the first grade 12) or grade around age 11 if or reception 7 half of high school) TK-12 student goes on to (transitional middle school; -

Social Selectivity of State Schools and the Impact of Grammars

_____________________________________________________________________________ Social selectivity of state schools and the impact of grammars A summary and discussion of findings from ‘Evidence on the effects of selective educational systems’ by the Centre for Evaluation and Monitoring at Durham University The Sutton Trust, October 2008 Contents Executive summary 3 Introduction and background 5 Findings -- selectivity 7 Findings – pupil intakes 10 Findings – attainment 12 Discussion 13 Proposed ways forward 16 Appendix 18 2 Executive summary Overview This study shows that the vast majority of England's most socially selective state secondary schools are non-grammar schools. However, England's remaining grammar schools are enrolling half as many academically able children from disadvantaged backgrounds as they could do. The research also concludes that the impact on the academic results of non-grammar state schools due to the ‘creaming off’ of pupils to grammar schools is negligible. Grammars have a widespread, low-level, impact on pupil enrolments across the sector. A relatively small number of non-selective schools do see a significant proportion of pupils ‘lost’ to nearby grammars, but this does not lead to lower academic achievement. The Trust proposes that a further study be undertaken to review ‘eleven plus’ selection tests to see whether they deter bright pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds applying to grammar schools, and urges more grammars to develop outreach schemes to raise the aspirations and achievement of children during primary school. It also backs calls for religious schools to consider straightforward 'binary' criteria to decide which pupils should be admitted on faith grounds, and other ways – including the use of banding and ballots – to help make admissions to all secondary state schools operate more equitably. -

Buckinghamshire Standing Advisory Council on Religious Education

Buckinghamshire Standing Advisory Council on Religious Education Annual Report 2017-18 Learning and growing through challenging RE 1 Contents Page No. Foreword from the Chair……………………………………………………………….. 1. Standards and quality of provision of RE: 2. Managing the SACRE and Partnership with the LA and Other Key Stakeholders: 3. Effectiveness of the Agreed Syllabus: 4. Collective Worship: 5. SACRE and School Improvement: Appendix 1: Examination data…………………….………………………………… Appendix 2: Diversity in Christianity ……………………………………………… Appendix 3: SACRE Membership and attendance for the year 2016/2017…… 2 Learning and growing through challenging RE Foreword from the Chair of SACRE September 2017 - July 2018 As with any organisation it is the inspiration given by the members that provides the character. I shall focus on some of the creativity we have valued in Bucks SACRE this year both from our members and during our visits to schools. In addition, we receive wise counsel from our Education Officer at Bucks CC, Katherine Wells and our RE Adviser Bill Moore. At our meeting in October we learned that Suma Din our Muslim deputy had become a school governor and would no longer fulfil her role with SACRE. However, her legacy to us is her book published by the Institute of Education Press entitled ‘Muslim Mothers and their children’s schooling.’ See SACRED 7, for a review. (For this and all other references to SACRED see the website at the end of this section). In her contribution to SACRED 6 Suma wrote; From the Qur’an, I understand my role as being a ‘steward’ on this earth; one who will take care, take responsibility and hand on a legacy to those who come after them. -

John Colet School Buckinghamshire HP22 6HF Tel: 01296 623348 Fax: 01296 622086 Email: [email protected]

Wharf Road Wendover, Aylesbury John Colet School Buckinghamshire HP22 6HF Tel: 01296 623348 Fax: 01296 622086 email: [email protected] John Colet School: a Company Limited by Guarantee. Registered in England; Company Number 7633408. Registered Office: John Colet School, Wharf Road, Wendover, Buckinghamshire, HP22 6HF INFORMATION FOR APPLICANTS Wendover is a village of some 7,000 people. It is situated about 35 miles to the north west of London, beautifully sited at the foot of the Chiltern scarp slope. To the south there are the Chiltern Hills and to the north, the Vale of Aylesbury. There is a main line link to Marylebone Station (45 minutes) and generally it is a most attractive area in which to live. The school draws its pupils from Wendover and the villages of Halton, Aston Clinton and Weston Turville. In August 2011 John Colet School converted to an Academy. The school is recognised throughout the County for the excellent education we offer our pupils. In 2014 our exam results at GCSE and in the Sixth Form were again a credit to our staff and pupils. The school is highly respected by the local community. We hope we have earned that respect – we intend to keep it! John Colet School shares its very attractive site with the Wendover Infant and Junior Schools and the school campus is used extensively for youth and community education activities. Over the past decade, the school has undergone major building/refurbishment. A new Humanities and Art block opened in September 2004. Our indoor swimming pool is also used by local primary schools and community swimming associations. -

Secondary and Post-Secondary Non-Tertiary Education

Published on Eurydice (https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice) This chapter covers the organisation and structure of educational provision for young people aged 11 to 18/19 years. For the purpose of this description, this provision is divided into: general lower secondary education [1] (for ages 11–16) general upper secondary education [2] (for ages 16–18/19) vocational upper secondary education [3] (for ages 16–18/19).* * In terms of International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) [4] categorisation, education for ages 11-14, is classified as ISCED 2; education for ages 14-18/19 as ISCED 3. There are no programmes categorised as post-secondary non-tertiary education (ISCED 4). For 16- to 18/19-year olds, there is a well-established tradition of subject specialisation, with the possibility of combining single subject general and vocational qualifications. More recently, the Government has introduced a policy on study programmes that applies across general and vocational education. For these reasons, the introduction to this chapter provides a combined description of general and vocational upper secondary education. General lower secondary education, ages 11-16 Young people enter secondary education at the age of 11 and, under Section 8 of the Education Act 1996 [5], full-time education is then compulsory up until the last Friday in June of the school year in which they reach the age of 16. Secondary schools cater for pupils from age 11 to either 16 or to 18/19. Study programmes Lower secondary education is divided into two key stages of the national curriculum [6]: Key Stage 3 - for pupils aged 11 to 14, ISCED 2 Key Stage 4 - for pupils aged 14 to 16, ISCED 3.