Amicus Brief

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sustaining a Historic High-Rise Structure

ctbuh.org/papers Title: Sustaining a Historic High-Rise Structure Authors: Nina Mahjoub, Project Engineer, Holmes Culley Megan Stringer, Project Engineer, Holmes Culley Bill Tremayne, Principal, Holmes Culley Subjects: Retrofit Seismic Keywords: Life Cycle Analysis Retrofit Seismic Structure Sustainability Publication Date: 2015 Original Publication: CTBUH Journal, 2015 Issue I Paper Type: 1. Book chapter/Part chapter 2. Journal paper 3. Conference proceeding 4. Unpublished conference paper 5. Magazine article 6. Unpublished © Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat / Nina Mahjoub; Megan Stringer; Bill Tremayne Retrofit / Seismic Sustaining a Historic High-Rise Structure One of the tallest seismic retrofits in North America was undertaken in the heart of San Francisco. The Pacific Telephone & Telegraph Company headquar- ters was an achievement of architecture of its day when completed in 1925, and it remains an emblem of the Art Deco movement. The building’s current owner decided to embark on the challenging endeavor of reviving the historic structure. This meant preserving the historic fabric, creating an open, flexible Nina A. Mahjoub Megan Stringer workspace, and infusing state-of-the-art technology and sustainability into all its aspects, including a voluntary full seismic structural upgrade. Introduction capacity of the existing building system. Moreover, this approach allows the engineer Situated in the heart of downtown San to better understand how the new and Francisco, the Pacific Telephone & Telegraph existing systems behave together during a (PT&T) Company headquarters opened in seismic event, and therefore provides a Bill Tremayne 1925, reaching 132.7 meters and becoming smart, more sustainable, and less obstructive the tallest building in the city upon solution while maintaining the historic fabric Authors completion (see Figure 1). -

Hilton San Francisco Union Square

Hilton San Francisco Union Square 36 37 33 22 23 24 26 15 333 O’Farrell Street, San Francisco, CA | 415-771-1400 11 THINGS TO DO A SHORT DISTANCE AWAY 34 1 Cable Cars – San Francisco’s cable car system is the world’s last manually 27 operated system. An icon of San Francisco, the cable car system forms part of the intermodal urban transport network operated by the San Francisco Municipal Railway. 2 Fisherman’s Wharf & Pier 39 – San Francisco’s most famous waterfront 7 community is one of the busiest and well known tourist attractions in the western United States. Explore our past, join in today’s fun, and catch a glimpse into the 8 future of Fisherman’s Wharf San Francisco! Home to two levels of unique specialty 19 5 28 38 shops that are surrounded by stunning views of the Golden Gate and Bay Bridges, Alcatraz Island and the famous San Francisco city skyline. 3 Alcatraz Island – Offers a close-up look at the site of the first lighthouse and US 6 built fort on the West Coast, the infamous federal penitentiary long off-limits to the public, and the history making 18 month occupation by Indians of All Tribes. Rich in 12 history, there is also a natural side to the Rock—gardens, tide pools, bird colonies, and bay views beyond compare. 9 4 San Francisco Zoo & Gardens – Connecting people with wildlife, inspiring caring for nature and advancing conservation action, the zoo is home to more than 2,000 exotic, endangered and rescued animals in 100 acres of majestic and peaceful 17 25 gardens located directly on the Pacific Coast. -

Before the Public Utilities Commission of the State Of

BEFORE THE PUBLIC UTILITIES COMMISSION OF THE FILED STATE OF CALIFORNIA 5-01-17 04:59 PM Order Instituting Rulemaking on the ) Commission’s Own Motion to Adopt Reporting ) R.92-08-008 Requirements for Electric, Gas, and Telephone ) (Filed August 11, 1992) Utilities Regarding Their Affiliate Transactions. ) CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE I hereby certify that, pursuant to the Commission’s Rules of Practice and Procedure, I have this day served a true copy of 2016 ANNUAL REPORT OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA EDISON COMPANY (U 338 E) ON SUBSIDIARY, AFFILIATE, AND HOLDING COMPANY TRANSACTIONS IN COMPLIANCE WITH R.92-08-008, ORDERING PARAGRAPH NO. 2 on all parties identified on the attached service list R.92-08-008. Service was effected by one or more means indicated below: ☒ Transmitting the copies via e-mail to all parties who have provided an e-mail address. ☒ Placing the copies in sealed envelopes and causing such envelopes to be delivered by hand or by overnight courier to the offices of the Assigned ALJ(s), or by U.S. mail to other addressee(s). Executed May 1, 2017, at Rosemead, California. /s/Jorge Martinez JORGE MARTINEZ SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA EDISON COMPANY 2244 Walnut Grove Avenue Post Office Box 800 Rosemead, California 91770 1 ************ SERVICE LIST *********** Last Updated on 09-MAR-2015 by: JVG R9208008 NOPOST ************** PARTIES ************** Margaret D.B. Brown Attorney At Law Jeffrey F. Beck PACIFIC BELL BECK & ACKERMAN 140 NEW MONTGOMERY ST., RM 1320 4 EMBARCADERO CENTER, SUITE 760 SAN FRANCISCO CA 94105 SAN FRANCISCO CA 94111 (415) 545-9424 (415) 263-7300 [email protected] David A. -

Statement of Qualifications

STATEMENT OF QUALIFICATIONS Page & Turnbull FIRM PROFILE Page & Turnbull is interested in the intersection between the built surroundings we have inherited and the way we live now. Our mission is to imagine change within historic environments through design, research, and technology. Page & Turnbull was established in 1973 as Charles Hall Page & Associates to provide architectural and conservation services for historic buildings, resources and civic areas. We were one of the first architecture firms in California to dedicate our practice to historic preservation and we are among the longest-practicing such firms in the country. Our offices are located in San Francisco, Sacramento and Los Angeles. Our staff includes licensed architects, designers and historians, conservators and planners. We approach projects with imagination and flexibility and are committed to the conservation of significant resources—where these resources can be made to function for present and future needs. Our services are oriented to our clients’ time and budget. All our professional staff meet or exceed the Secretary of the Interior’s Historic Preservation Professional Qualification Standards. ARCHITECTURAL SERVICES We emphasize the re-use of existing buildings and the thoughtful application of new design. Solutions for new construction respect existing architectural values and the context of neighboring structures. When analyzing buildings we are skilled in the assessment and treatment of the most significant architectural and historical spaces and elements. We welcome the challenge of solving problems of repair, seismic strengthening, and integrating new systems. Page & Turnbull ensures that projects comply with the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Rehabilitation for local, state and federal agency review. -

San Francisco Planning Code

Print San Francisco Planning Code ARTICLE 11: PRESERVATION OF BUILDINGS AND DISTRICTS OF ARCHITECTURAL, HISTORICAL, AND AESTHETIC IMPORTANCE IN THE C-3 DISTRICTS Sec. 1101. Findings and Purposes. Sec. 1102. Standards for Designation of Buildings. Sec. 1102.1. Designation of Buildings. Sec. 1103. Standards for Designation of Conservation Districts. Sec. 1103.1. Conservation District Designations. Procedures for Change of Designation and Designation of Additional Significant and Sec. 1106. Contributory Buildings. Procedures for Designation of Additional Conservation Districts or Boundary Change Sec. 1107. of Conservation Districts. Sec. 1108. Notice of Designation. Sec. 1109. Preservation Lots: Eligibility for Transfer of Development Rights. Construction, Alteration or Demolition of Significant or Contributory Buildings or Sec. 1110. Buildings in Conservation Districts. Applications for Permits to Alter, Permits to Demolish, and Permits for New Sec. 1111. Construction in Conservation Districts. Sec. 1111.1. Determination of Minor and Major Alterations. Sec. 1111.2. Sign Permits. Sec. 1111.3. Review by the Planning Department. Sec. 1111.4. Scheduling and Notice of Historic Preservation Commission Hearings. Sec. 1111.5. Decision by the Historic Preservation Commission. Sec. 1111.6. Standards and Requirements for Review of Applications for Alterations. Sec. 1111.7. Standards and Requirements for Review of Applications for Demolition. Sec. 1113. Standards of Review for New and Replacement Construction in Conservation Districts. Sec. 1114. Modification of a Decision of the Historic Preservation Commission. Sec. 1115. Appeal. Sec. 1116. Unlawful Alteration or Demolition. Sec. 1117. Conformity with Other City Permit Processes. Sec. 1118. Unsafe or Dangerous Conditions. Sec. 1119. Maintenance Requirements and Enforcement Thereof. Sec. 1120. Enforcement and Penalties. Sec. -

140 New Montgomery Street Jade Signature

Search Tags: High Rise Project Count: 30 140 New Montgomery Street San Francisco, CA Project Contacts: Carolyn Searls Completed in the mid-1920s, 140 New Montgomery Street is one of the early skyscrapers built in San Francisco. The Art Deco high-rise, originally known as the Pacific Telephone and Telegraph... Services: Building Enclosure Rehabilitation Markets: Office Keywords: Adaptive Reuse, Award Winning, Glass and Glazing, High Rise, Historic, Masonry, Masonry-Terra Cotta, National Register of Historic Places, Preservation Technology , Roof Replacement, Roofing, Windows Jade Signature Miami, FL Project Contacts: Jeffry Ceruti, Sean Homem With an oceanfront site and three floors of amenities, the Jade Signature brings a resort experience to residents’ everyday life. The fifty-five-story condominium building features an exposed cast... Services: Building Enclosure Design, Structural Design Keywords: Balcony, Below-Ground Waterproofing, Concrete, Drainage, High Rise, Residential, Waterproofing The Avery, Transbay Block 8, 400-450 Folsom Street San Francisco, CA Project Contacts: Craig Allender, Xiu Li The mixed-use development at 400 Folsom Street includes a fifty-five-story tower (The Avery) and two low-rise buildings designed by the executive architecture team of Office for Metropolitan... Services: Building Enclosure Design Keywords: Below-Ground Waterproofing, Curtain Wall, High Rise, Masonry-Brick, Plaza, Residential, Retail, Roofing, Waterproofing, Windows The Eddy, New Street Boston, MA Project Contacts: Jeffry Ceruti, Christopher Grey The Eddy, a new residential development, sits along the waterfront in East Boston. The property includes 258 rental units in a seventeen-story tower and four-story building. In addition to views... Services: Building Enclosure Design Keywords: Curtain Wall, High Rise, Preengineered/Prefabricated/Modular, Residential, Roofing, Roofing, Low-Sloped, Windows 200 North LaSalle Chicago, IL Project Contacts: Peter Babaian The Class A office building is located at 200 North LaSalle Drive in the heart of Chicago’s Loop. -

Lpd R9807038 List

APPENDIX E ************ SERVICE LIST *********** Last Update on 13-FEB-2001 by: LPD R9807038 LIST ************ APPEARANCES ************ Marco Gomez Attorney At Law Peter A. Casciato BAY AREA RAPID TRANSIT DISTRICT Attorney At Law 800 MADISON STREET, 5TH FLOOR A PROFESSIONAL CORPORATION OAKLAND CA 94607 8 CALIFORNIA STREET, SUITE 701 (510) 464-6058 SAN FRANCISCO CA 94111-4825 [email protected] (415) 291-8661 [email protected] Jeffrey F. Beck, J. Bronfman For: Time Warner Connect/NorthPoint Communications, Inc./Central JILLISA BRONFMAN Wireless Partnership Attorney At Law BECK & ACKERMAN Dorothy Connelly FOUR EMBARCADERO CENTER, SUITE 760 Director, Government Relations SAN FRANCISCO CA 94111 AIRTOUCH COMMUNICATIONS, INC. (415) 263-7302 ONE CALIFORNIA STREET, 29TH FLOOR [email protected] SAN FRANCISCO CA 94111 For: Evans/GTE West Coast/Happy (415) 658-2063 Valley/Hornitos/Kerman/Pinnacles/Siskiyou/Volcano/Winterhaven Michele F. Joy Darlene Clark General Counsel Staff Attorney ASSOCIATION OF OIL PIPE LINES CALIFORNIA CABLE TELEVISION ASSN. 1101 VERMONT AVENUE N.W. STE 604 PO BOX 11080 WASHINGTON DC 20005-3521 OAKLAND CA 94611-0080 (202) 408-7970 (510) 428-2225 [email protected] [email protected] For: ASSOCIATION OF OIL PIPE LINES Richard J. Balocco Randolph W. Deutsch President Attorney At Law CALIFORNIA WATER ASSOCIATION AT&T COMMUNICATIONS OF CALIFORNIA, INC. 374 W. SANTA CLARA STREET 795 FOLSOM STREET, ROOM 690 SAN JOSE CA 95196 SAN FRANCISCO CA 94107 (408) 279-7860 (415) 442-5560 [email protected] Robert Green Joint Venture & Regulatory Specialist Tom Dukich CHEVRON PIPE LINE COMPANY AVISTA CORP PO BOX 4879 PO BOX 3727 HOUSTON TX 77210-4879 SPOKANE WA 99220-3727 (281) 596-3518 (509) 482-4724 [email protected] [email protected] For: WP Natural Gas Charles E. -

Transit Center District Plan and Transit Tower

COMMENTS AND RESPONSES ON DRAFT EIR Transit Center District Plan and Transit Tower PLANNING DEPARTMENT CASE NO. 2007.0558E and 2008.0789E STATE CLEARINGHOUSE NO. 2008072073 Draft EIR Publication Date: SEPTEMBER 28, 2011 Draft EIR Public Hearing Date: NOVEMBER 3, 2011 Draft EIR Public Comment Period: SEPTEMBER 28 THROUGH NOVEMBER 28, 2011 Final EIR Certication Date: MAY 24, 2012 May 10, 2012 To: Members of the Planning Commission and Interested Parties From: Bill Wycko, Environmental Review Officer Re: Attached Comments and Responses on Draft Environmental Impact Report Case No. 2007.0558E: Transit Center District Plan and Case No. 2008.0789 Transit Tower Attached for your review please find a copy of the Comments and Responses document for the Draft Environmental Impact Report (EIR) for the above‐referenced project. This document, along with the Draft EIR, will be before the Planning Commission for Final EIR certification on May 24, 2012. Please note that the public review period ended on November 28, 2011. The Planning Commission does not conduct a hearing to receive comments on the Comments and Responses document, and no such hearing is required by the California Environmental Quality Act. Interested parties, however, may always write to Commission members or to the President of the Commission at 1650 Mission Street and express an opinion on the Comments and Responses document, or the Commission’s decision to certify the completion of the Final EIR for this project. Please note that if you receive the Comments and Responses document in addition to the Draft EIR, you technically have the Final EIR. If you have any questions concerning the Comments and Responses document or the environmental review process, please contact Sarah B. -

San Francisco Office Market Monitor Partnership

San Francisco Office Market Monitor partnership. performance.. Q2 2012 Market Facts Market Takeaway Vacancy Rates Fueled by a booming technology sector, San Francisco’s office market 20.0% continues to surpass the nation in a range of major indicators. 15.0% San Francisco’s unemployment rate declined to 7.4 percent in May after 10.0% hovering near the 8 percent national average at the start of the year. Job growth, primarily driven by the technology sector, is helping to fuel the current 5.0% period of strong leasing activity. Across the city vacancy rates are down an average of 3.6 percent from a year ago, and nearly 1 percent lower than last 0.0% quarter. Vacancy rates have steadily declined in the last two and a half years YE06 YE07 YE08 YE09 YE10 YE11 2Q12 with the past few quarters taking on steeper decreases. In highly competitive neighborhoods like SOMA, Class A buildings have a mere 2.6 percent vacancy rate, and a notable average asking rent of $57.50 per square foot (psf) full Asking Rents service. This quarter marks the two year point for consecutive quarters of positive absorption. Young, rapidly growing, and highly successful tech companies (fittingly named “gazelles”) have led the way in both newly signed leases and large moves this past quarter. Social media companies like Twitter (215,000 sf) helped establish some of the largest sweeps in absorption. Airbnb and Yelp, two other gazelles, inked two of the top five leases for a combined 264,800 sf. Even with planned renovations and some new construction, relatively little supply is expected to be added to San Francisco’s office market. -

The Investment Landscape PRIEST CLAY ST

FISHERMAN'S P WHARF JEFFERSON ST. P P P P P P BEACH ST. P P P P P NORTHPOINT ST. COLUMBUS ST P P . P P BAY ST. BAY ST. ST . AY E VANDEWATER ST. RT MIDW HA P BRET WORDEN ST FRANCISCO ST. FRANCISCO ST. THE EMBARCADERO P WATER ST. HOUSTON ST. PFEIFFER ST. AIR ST BELL CHESTNUT ST. CHESTNUT ST. ST A VENARD P . ST CULEBR WINTHRO NEWELL P 101 LOMBARD ST. LOMBARD ST. P . TELEGRAPH STONE BLACK HILL JANSEN ST GREENWICH ST. GREENWICH ST. T E L E ROACH ST G VALPARAISO ST. R A HARRIS PL. P 101 H RUSSIAN HILL B L V TRIDGE D . AT FILBERT ST. FILBERT ST. HAVENS ST. REDFIELD ALLADIN TER. E ALLEN ST. HASTINGS MOOR MARION PL BLACK PL UNION ST. UNION ST. P WARNER SHAR ROCKLAND . RUSSELL ST. MACONDRAY LN. P DELGADO . P . HAMLIN EASTMAN ST ST Y GREEN ST. TH ST GREEN ST. VE. VE. ST . ST . A . A ST ST ST T RY T A ON ST . VENWOR VI BONITA ST. TTE TA POWELL YLOR ST GRAN N NESS P POLK ST MONTGOMER LEA FRON BA OCKT JONES ST HYDE ST LARKIN ST GOUGH ST WHITE ST KEARNY TA MASON ST OC SANSOME ST VA FRANKLIN ST ST RUSSIAN HILL VALLEJO ST. VALLEJO ST. P . P WALDO GLOVER ST. VIS ST DA BROADWAY BROADWAY S . CYRU ST BERNHARD ST. LYNCH ST. YNE PL COLUMBUS ST SALMON ST WA HIMMELMAN ST MORRELL PACIFIC AVE. PACIFIC AVE. K . P P . BURGOYNE McCORMAC . PL AUBURN ST P LL WA JACKSON ST. -

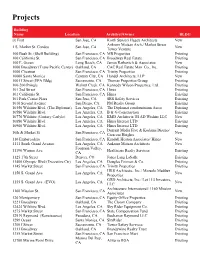

View Projects

Projects Building Name Location Architect/Owner BLDG @ First San Jose, CA Korth Sunseri Hagey Architects New Ankrom Moisan Arch./ Market Street 1 S. Market St. Condos San Jose, CA New Tower Venture 100 Bush St. (Shell Building) San Francisco, CA MB Properties Existing 100 California St. San Francisco, CA Broadway Real Estate Existing 100 E. Ocean Long Beach, CA James Ratkovich & Associates New 1000 Broadway (Trans Pacific Center) Oakland, CA CAC Real Estate Man. Co., Inc. Existing 1000 Chestnut San Francisco, CA Trinity Properties Existing 10000 Santa Monica Century City, CA Handel Architects, LLP New 1001 I Street (EPA Bldg) Sacramento, CA Thomas Properties Group Existing 100-200 Pringle Walnut Creek, CA Kennedy Wilson Properties, Ltd. Existing 101 2nd Street San Francisco, CA Hines Existing 101 California St. San Francisco, CA Hines Existing 101 Park Center Plaza San Jose, CA SRS Safety Services Existing 1010 Second Avenue San Diego, CA PM Realty Group Existing 10350 Wilshire Blvd. (The Diplomat) Los Angeles, CA The Diplomat condominium Assoc Existing 10580 Wilshire Blvd. Los Angeles, CA B & G Construction Existing 10776 Wilshire (Century Carlyle) Los Angeles, CA KMD Architects/ El AD Wishire LLC New 10880 Wilshire Blvd. Los Angeles, CA Hines Interest LTD Existing 10960 Wilshire Blvd. Los Angeles, CA Hines Interest LTD Existing Durrant Media Five & Kodama Diseno/ 10th & Market St. San Francisco, CA New Crescent Heights 110 Embarcadero San Francisco, CA Kendall Heaton Associates/ Hines New 1111 South Grand Avenue Los Angeles, CA Ankrom Moisan Architects New Fountain Valley, 11190 Warner Ave. Healthcare Realty Services Existing CA 1125 17th Street Denver, CO Jones Lang LaSalle Existing 11400 Olympic Blvd (Executive Ctr) Los Angeles, CA Douglas Emmett & Co. -

LANDMARK DESIGNATION REPORT Phillips Building, 246 First Street November 8, 2017

Architecture Planning Conservation Landmark DesignaƟ on Report The Phillips Building Prepared for San Francisco Planning Department Prepared by Architectural Resource Group, Inc. San Francisco, California November 8, 2017 LANDMARK DESIGNATION REPORT Phillips Building, 246 First Street November 8, 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Overview ................................................................................................................................................. 1 2. Building Description ............................................................................................................................... 2 3. Construction History ............................................................................................................................... 3 4. Occupant and Ownership History .......................................................................................................... 9 5. Phillips & Van Orden Company. ............................................................................................................. 9 6. The Early Twentieth Century Printing Industry in San Francisco ........................................................ 14 7. Master Architect: Henry H. Meyers and George Klinkhardt ................................................................ 16 8. Architectural Context ........................................................................................................................... 21 9. Statement of Significance ....................................................................................................................