Blue-Grey Taildropper Prophysaon Coeruleum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

San Gabriel Chestnut ESA Petition

BEFORE THE SECRETARY OF THE INTERIOR PETITION TO THE U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE TO PROTECT THE SAN GABRIEL CHESTNUT SNAIL UNDER THE ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT © James Bailey CENTER FOR BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY Notice of Petition Ryan Zinke, Secretary U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Greg Sheehan, Acting Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1849 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Paul Souza, Director Region 8 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Pacific Southwest Region 2800 Cottage Way Sacramento, CA 95825 [email protected] Petitioner The Center for Biological Diversity is a national, nonprofit conservation organization with more than 1.3 million members and supporters dedicated to the protection of endangered species and wild places. http://www.biologicaldiversity.org Failure to grant the requested petition will adversely affect the aesthetic, recreational, commercial, research, and scientific interests of the petitioning organization’s members and the people of the United States. Morally, aesthetically, recreationally, and commercially, the public shows increasing concern for wild ecosystems and for biodiversity in general. 1 November 13, 2017 Dear Mr. Zinke: Pursuant to Section 4(b) of the Endangered Species Act (“ESA”), 16 U.S.C. §1533(b), Section 553(3) of the Administrative Procedures Act, 5 U.S.C. § 553(e), and 50 C.F.R. §424.14(a), the Center for Biological Diversity and Tierra Curry hereby formally petition the Secretary of the Interior, through the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (“FWS”, “the Service”) to list the San Gabriel chestnut snail (Glyptostoma gabrielense) as a threatened or endangered species under the Endangered Species Act and to designate critical habitat concurrently with listing. -

Slugs of Britain & Ireland

TEST VERSION 2013 SLUGS OF BRITAIN & IRELAND (Short test version, pages 18-37 only) By Ben Rowson, James Turner, Roy Anderson & Bill Symondson PRODUCED BY FSC 2013. TEXT AND PHOTOS © NATIONAL MUSEUM OF WALES 2013 External features of slugs Tail Mantle Head Keel Tubercles Lateral bands Genital pore Identification of Slugs Identification Tentacles. Breathing pore (pneumostome) Keel Eyes Variations in lateral banding Mantle markings and ridges Broken lateral bands Mouth Solid lateral bands Sole (underside of foot) Mantle. Note texture and presence of grooves and ridges, as Tubercles. Note whether numerous and small/fine vs. few and well as any markings and banding. large/coarse. Pigment may be present in the grooves between tubercles. Tentacles. Note colour. Slugs may need to be handled or disturbed to extend tentacles. Keel (raised ridge). Note length and whether truncated at the tip of tail. Beware markings that may exaggerate or obscure the Breathing pore (pneumostome). length of keel. On right-hand side of body. Note whether rim is noticeably paler or darker than body sides. Sole (underside of foot). Note colour and any patterning. The sole in most slugs is tripartite i.e. there are three fields running Lateral bands. Note whether present on mantle and/or tail. in parallel the length of the animal. Is the central field a different Note also intensity, whether broad or narrow, and whether high shade from the lateral fields or low on body side. Shell Dorsal grooves. In Testacellidae, note wheth- Mucus pore. er the two grooves meet in front of the shell or Present only in Arionidae underneath it. -

Conservation Assessment for Cryptomastix Hendersoni

Conservation Assessment for Cryptomastix hendersoni, Columbia Oregonian Cryptomastix hendersoni, photograph by Bill Leonard, used with permission. Originally issued as Management Recommendations February 1999 by John S. Applegarth Revised Sept 2005 by Nancy Duncan Updated April 2015 By: Sarah Foltz Jordan & Scott Hoffman Black (Xerces Society) Reviewed by: Tom Burke USDA Forest Service Region 6 and USDI Bureau of Land Management, Oregon and Washington Interagency Special Status and Sensitive Species Program Cryptomastix hendersoni - Page 1 Preface Summary of 2015 update: The framework of the original document was reformatted to more closely conform to the standards for the Forest Service and BLM for Conservation Assessment development in Oregon and Washington. Additions to this version of the Assessment include NatureServe ranks, photographs of the species, and Oregon/Washington distribution maps based on the record database that was compiled/updated in 2014. Distribution, habitat, life history, taxonomic information, and other sections in the Assessment have been updated to reflect new data and information that has become available since earlier versions of this document were produced. A textual summary of records that have been gathered between 2005 and 2014 is provided, including number and location of new records, any noteworthy range extensions, and any new documentations on FS/BLM land units. A complete assessment of the species’ occurrence on Forest Service and BLM lands in Oregon and Washington is also provided, including relative abundance on each unit. Cryptomastix hendersoni - Page 2 Table of Contents Preface 1 Executive Summary 4 I. Introduction 6 A. Goal 6 B. Scope 6 C. Management Status 6 II. Classification and Description 7 A. -

Haida Gwaii Slug,Staala Gwaii

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Haida Gwaii Slug Staala gwaii in Canada SPECIAL CONCERN 2013 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2013. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Haida Gwaii Slug Staala gwaii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. x + 44 pp. (www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/default_e.cfm). Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Kristiina Ovaska and Lennart Sopuck of Biolinx Environmental Research Inc., for writing the status report on Haida Gwaii Slug, Staala gwaii, in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada. This report was overseen and edited by Dwayne Lepitzki, Co-chair of the COSEWIC Molluscs Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur la Limace de Haida Gwaii (Staala gwaii) au Canada. Cover illustration/photo: Haida Gwaii Slug — Photo by K. Ovaska. Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2013. Catalogue No. CW69-14/673-2013E-PDF ISBN 978-1-100-22432-9 Recycled paper COSEWIC Assessment Summary Assessment Summary – May 2013 Common name Haida Gwaii Slug Scientific name Staala gwaii Status Special Concern Reason for designation This small slug is a relict of unglaciated refugia on Haida Gwaii and on the Brooks Peninsula of northwestern Vancouver Island. -

ED45E Rare and Scarce Species Hierarchy.Pdf

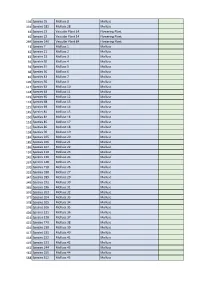

104 Species 55 Mollusc 8 Mollusc 334 Species 181 Mollusc 28 Mollusc 44 Species 23 Vascular Plant 14 Flowering Plant 45 Species 23 Vascular Plant 14 Flowering Plant 269 Species 149 Vascular Plant 84 Flowering Plant 13 Species 7 Mollusc 1 Mollusc 42 Species 21 Mollusc 2 Mollusc 43 Species 22 Mollusc 3 Mollusc 59 Species 30 Mollusc 4 Mollusc 59 Species 31 Mollusc 5 Mollusc 68 Species 36 Mollusc 6 Mollusc 81 Species 43 Mollusc 7 Mollusc 105 Species 56 Mollusc 9 Mollusc 117 Species 63 Mollusc 10 Mollusc 118 Species 64 Mollusc 11 Mollusc 119 Species 65 Mollusc 12 Mollusc 124 Species 68 Mollusc 13 Mollusc 125 Species 69 Mollusc 14 Mollusc 145 Species 81 Mollusc 15 Mollusc 150 Species 84 Mollusc 16 Mollusc 151 Species 85 Mollusc 17 Mollusc 152 Species 86 Mollusc 18 Mollusc 158 Species 90 Mollusc 19 Mollusc 184 Species 105 Mollusc 20 Mollusc 185 Species 106 Mollusc 21 Mollusc 186 Species 107 Mollusc 22 Mollusc 191 Species 110 Mollusc 23 Mollusc 245 Species 136 Mollusc 24 Mollusc 267 Species 148 Mollusc 25 Mollusc 270 Species 150 Mollusc 26 Mollusc 333 Species 180 Mollusc 27 Mollusc 347 Species 189 Mollusc 29 Mollusc 349 Species 191 Mollusc 30 Mollusc 365 Species 196 Mollusc 31 Mollusc 376 Species 203 Mollusc 32 Mollusc 377 Species 204 Mollusc 33 Mollusc 378 Species 205 Mollusc 34 Mollusc 379 Species 206 Mollusc 35 Mollusc 404 Species 221 Mollusc 36 Mollusc 414 Species 228 Mollusc 37 Mollusc 415 Species 229 Mollusc 38 Mollusc 416 Species 230 Mollusc 39 Mollusc 417 Species 231 Mollusc 40 Mollusc 418 Species 232 Mollusc 41 Mollusc 419 Species 233 -

Arthropod Diversity and Conservation in Old-Growth Northwest Forests'

AMER. ZOOL., 33:578-587 (1993) Arthropod Diversity and Conservation in Old-Growth mon et al., 1990; Hz Northwest Forests complex litter layer 1973; Lattin, 1990; JOHN D. LATTIN and other features Systematic Entomology Laboratory, Department of Entomology, Oregon State University, tural diversity of th Corvallis, Oregon 97331-2907 is reflected by the 14 found there (Lawtt SYNOPSIS. Old-growth forests of the Pacific Northwest extend along the 1990; Parsons et a. e coastal region from southern Alaska to northern California and are com- While these old posed largely of conifer rather than hardwood tree species. Many of these ity over time and trees achieve great age (500-1,000 yr). Natural succession that follows product of sever: forest stand destruction normally takes over 100 years to reach the young through successioi mature forest stage. This succession may continue on into old-growth for (Lattin, 1990). Fire centuries. The changing structural complexity of the forest over time, and diseases, are combined with the many different plant species that characterize succes- bances. The prolot sion, results in an array of arthropod habitats. It is estimated that 6,000 a continually char arthropod species may be found in such forests—over 3,400 different ments and habitat species are known from a single 6,400 ha site in Oregon. Our knowledge (Southwood, 1977 of these species is still rudimentary and much additional work is needed Lawton, 1983). throughout this vast region. Many of these species play critical roles in arthropods have lx the dynamics of forest ecosystems. They are important in nutrient cycling, old-growth site, tt as herbivores, as natural predators and parasites of other arthropod spe- mental Forest (HJ cies. -

Interior Columbia Basin Mollusk Species of Special Concern

Deixis l-4 consultants INTERIOR COLUMl3lA BASIN MOLLUSK SPECIES OF SPECIAL CONCERN cryptomasfix magnidenfata (Pilsbly, 1940), x7.5 FINAL REPORT Contract #43-OEOO-4-9112 Prepared for: INTERIOR COLUMBIA BASIN ECOSYSTEM MANAGEMENT PROJECT 112 East Poplar Street Walla Walla, WA 99362 TERRENCE J. FREST EDWARD J. JOHANNES January 15, 1995 2517 NE 65th Street Seattle, WA 98115-7125 ‘(206) 527-6764 INTERIOR COLUMBIA BASIN MOLLUSK SPECIES OF SPECIAL CONCERN Terrence J. Frest & Edward J. Johannes Deixis Consultants 2517 NE 65th Street Seattle, WA 98115-7125 (206) 527-6764 January 15,1995 i Each shell, each crawling insect holds a rank important in the plan of Him who framed This scale of beings; holds a rank, which lost Would break the chain and leave behind a gap Which Nature’s self wcuid rue. -Stiiiingfieet, quoted in Tryon (1882) The fast word in ignorance is the man who says of an animal or plant: “what good is it?” If the land mechanism as a whole is good, then every part is good, whether we understand it or not. if the biota in the course of eons has built something we like but do not understand, then who but a fool would discard seemingly useless parts? To keep every cog and wheel is the first rule of intelligent tinkering. -Aido Leopold Put the information you have uncovered to beneficial use. -Anonymous: fortune cookie from China Garden restaurant, Seattle, WA in this “business first” society that we have developed (and that we maintain), the promulgators and pragmatic apologists who favor a “single crop” approach, to enable a continuous “harvest” from the natural system that we have decimated in the name of profits, jobs, etc., are fairfy easy to find. -

The Slugs of Bulgaria (Arionidae, Milacidae, Agriolimacidae

POLSKA AKADEMIA NAUK INSTYTUT ZOOLOGII ANNALES ZOOLOGICI Tom 37 Warszawa, 20 X 1983 Nr 3 A n d rzej W ik t o r The slugs of Bulgaria (A rionidae , M ilacidae, Limacidae, Agriolimacidae — G astropoda , Stylommatophora) [With 118 text-figures and 31 maps] Abstract. All previously known Bulgarian slugs from the Arionidae, Milacidae, Limacidae and Agriolimacidae families have been discussed in this paper. It is based on many years of individual field research, examination of all accessible private and museum collections as well as on critical analysis of the published data. The taxa from families to species are sup plied with synonymy, descriptions of external morphology, anatomy, bionomics, distribution and all records from Bulgaria. It also includes the original key to all species. The illustrative material comprises 118 drawings, including 116 made by the author, and maps of localities on UTM grid. The occurrence of 37 slug species was ascertained, including 1 species (Tandonia pirinia- na) which is quite new for scientists. The occurrence of other 4 species known from publications could not bo established. Basing on the variety of slug fauna two zoogeographical limits were indicated. One separating the Stara Pianina Mountains from south-western massifs (Pirin, Rila, Rodopi, Vitosha. Mountains), the other running across the range of Stara Pianina in the^area of Shipka pass. INTRODUCTION Like other Balkan countries, Bulgaria is an area of Palearctic especially interesting in respect to malacofauna. So far little investigation has been carried out on molluscs of that country and very few papers on slugs (mostly contributions) were published. The papers by B a b o r (1898) and J u r in ić (1906) are the oldest ones. -

The Land Snails of Lichadonisia Islets (Greece)

Ecologica Montenegrina 39: 59-68 (2021) This journal is available online at: www.biotaxa.org/em http://dx.doi.org/10.37828/em.2021.39.6 The land snails of Lichadonisia islets (Greece) GALATEA GOUDELI1*, ARISTEIDIS PARMAKELIS1, KONSTANTINOS PROIOS1, IOANNIS ANASTASIOU2, CANELLA RADEA1, PANAYIOTIS PAFILIS2, 3 & KOSTAS A. TRIANTIS1,4* 1Section of Ecology and Taxonomy, Department of Biology, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Panepistimioupolis, 15784 Athens, Greece Emails: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] 2Section of Zoology and Marine Biology, Department of Biology, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Panepistimioupolis, 15784 Athens, Greece Emails: [email protected]; [email protected] 3Zoological Museum, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, 15784 Athens, Greece 4Natural Environment and Climate Change Agency, Villa Kazouli, 14561 Athens, Greece *Corresponding authors Received 12 January 2021 │ Accepted by V. Pešić: 30 January 2021 │ Published online 8 February 2021. Abstract The Lichadonisia island group is located between Maliakos and the North Evian Gulf, in central Greece. Lichadonisia is one of the few volcanic island groups of Greece, consisting mainly of lava flows. Today the islands are uninhabited with high numbers of visitors, but permanent population existed for many decades in the past. Herein, we present for the first time the land snail fauna of the islets and we compare their species richness with islands of similar size across the Aegean Sea. This group of small islands, provides a typical example on how human activities in the current geological era, i.e., the Anthropocene, alter the natural communities and differentiate biogeographical patterns. -

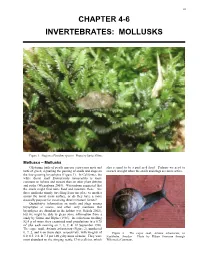

BRYOLOGICAL INTERACTION-Chapter 4-6

65 CHAPTER 4-6 INVERTEBRATES: MOLLUSKS Figure 1. Slug on a Fissidens species. Photo by Janice Glime. Mollusca – Mollusks Glistening trails of pearly mucous criss-cross mats and also seemed to be a preferred food. Perhaps we need to turfs of green, signalling the passing of snails and slugs on searach at night when the snails and slugs are more active. the low-growing bryophytes (Figure 1). In California, the white desert snail Eremarionta immaculata is more common on lichens and mosses than on other plant detritus and rocks (Wiesenborn 2003). Wiesenborn suggested that the snails might find more food and moisture there. Are these mollusks simply travelling from one place to another across the moist moss surface, or do they have a more dastardly purpose for traversing these miniature forests? Quantitative information on snails and slugs among bryophytes is scarce, and often only mentions that bryophytes are abundant in the habitat (e.g. Nekola 2002), but we might be able to glean some information from a study by Grime and Blythe (1969). In collections totalling 82.4 g of moss, they examined snail populations in a 0.75 m2 plot each morning on 7, 8, 9, & 12 September 1966. The copse snail, Arianta arbustorum (Figure 2), numbered 0, 7, 2, and 6 on those days, respectively, with weights of Figure 2. The copse snail, Arianta arbustorum, in 0.0, 8.5, 2.4, & 7.3 per 100 g dry mass of moss. They were Stockholm, Sweden. Photo by Håkan Svensson through most abundant on the stinging nettle, Urtica dioica, which Wikimedia Commons. -

Fauna of New Zealand Ko Te Aitanga Pepeke O Aotearoa

aua o ew eaa Ko te Aiaga eeke o Aoeaoa IEEAE SYSEMAICS AISOY GOU EESEAIES O ACAE ESEAC ema acae eseac ico Agicuue & Sciece Cee P O o 9 ico ew eaa K Cosy a M-C aiièe acae eseac Mou Ae eseac Cee iae ag 917 Aucka ew eaa EESEAIE O UIESIIES M Emeso eame o Eomoogy & Aima Ecoogy PO o ico Uiesiy ew eaa EESEAIE O MUSEUMS M ama aua Eiome eame Museum o ew eaa e aa ogaewa O o 7 Weigo ew eaa EESEAIE O OESEAS ISIUIOS awece CSIO iisio o Eomoogy GO o 17 Caea Ciy AC 1 Ausaia SEIES EIO AUA O EW EAA M C ua (ecease ue 199 acae eseac Mou Ae eseac Cee iae ag 917 Aucka ew eaa Fauna of New Zealand Ko te Aitanga Pepeke o Aotearoa Number / Nama 38 Naturalised terrestrial Stylommatophora (Mousca Gasooa Gay M ake acae eseac iae ag 317 amio ew eaa 4 Maaaki Whenua Ρ Ε S S ico Caeuy ew eaa 1999 Coyig © acae eseac ew eaa 1999 o a o is wok coee y coyig may e eouce o coie i ay om o y ay meas (gaic eecoic o mecaica icuig oocoyig ecoig aig iomaio eiea sysems o oewise wiou e wie emissio o e uise Caaoguig i uicaio AKE G Μ (Gay Micae 195— auase eesia Syommaooa (Mousca Gasooa / G Μ ake — ico Caeuy Maaaki Weua ess 1999 (aua o ew eaa ISS 111-533 ; o 3 IS -7-93-5 I ie 11 Seies UC 593(931 eae o uIicaio y e seies eio (a comee y eo Cosy usig comue-ase e ocessig ayou scaig a iig a acae eseac M Ae eseac Cee iae ag 917 Aucka ew eaa Māoi summay e y aco uaau Cosuas Weigo uise y Maaaki Weua ess acae eseac O o ico Caeuy Wesie //wwwmwessco/ ie y G i Weigo o coe eoceas eicuaum (ue a eigo oaa (owe (IIusao G M ake oucio o e coou Iaes was ue y e ew eaIa oey oa ue oeies eseac -

Omus Audouini

Omus audouini English name Audouin’s Night-stalking Tiger Beetle Scientific name Omus audouini Family Carabidae (Ground and Tiger Beetles) Tribe Cicindelini (Tiger Beetles) Other scientific names Omus ambiguus, O. borealis, O. californicus audouini, O. cephalicus audens, O. oregonensis, O. rugipennis, O. solidulus Risk status BC: critically imperilled (S1); Red-listed; BC Conservation Framework Highest Priority: 1 (Goal 3, Global response) Canada: may be at risk (N2); COSEWIC: not yet assessed, status report commissioned (2012) Global: secure (G5) Elsewhere: Washington – secure (S5); Oregon – secure (S5); California – apparently secure (S4) Range/Known distribution Audouin’s Night-stalking Tiger Beetle occurs in coastal western North BRITISH America from extreme southwestern COLUMBIA British Columbia to northwestern California. A few inland records are known from central southern Wash- ington and southwestern Oregon. In Canada, this species is restricted to a small area of the Georgia Basin on southeastern Vancouver Island in N and around Victoria (one recent and several historical records) and the adjacent mainland in the Boundary COMOX Bay area (one historical and several PORT recent records). ALBERNI VANCOUVER NANAIMO Field description Adults. Adult Omus are “tiger DUNCAN beetles”, part of the “ground and tiger beetle” family Carabidae. Adult Carabidae can be distinguished VICTORIA from almost all other beetles by the large fused plate covering most of Distribution of Omus audouini the first abdominal segment at the l Recently confirmed sites l Historical sites base of the hind pair of legs. Tiger beetle adults are active predators with large eyes, distinctive sickle-like mandibles, and thread-like 11-segmented antennae attached to the upper edge of the clypeus (above the mandibles).