SAINT FRANCIS of ASSISI Bihil ©Bstat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assumption Parking Lot Rosary.Pub

Thank you for joining in this celebration Please of the Blessed Mother and our Catholic park in a faith. Please observe these guidelines: designated Social distancing rules are in effect. Please maintain 6 feet distance from everyone not riding parking with you in your vehicle. You are welcome to stay in your car or to stand/ sit outside your car to pray with us. space. Anyone wishing to place their own flowers before the statue of the Blessed Mother and Christ Child may do so aer the prayers have concluded, but social distancing must be observed at all mes. Please present your flowers, make a short prayer, and then return to your car so that the next person may do so, and so on. If you wish to speak with others, please remember to wear a mask and to observe 6 foot social distancing guidelines. Opening Hymn—Hail, Holy Queen Hail, holy Queen enthroned above; O Maria! Hail mother of mercy and of love, O Maria! Triumph, all ye cherubim, Sing with us, ye seraphim! Heav’n and earth resound the hymn: Salve, salve, salve, Regina! Our life, our sweetness here below, O Maria! Our hope in sorrow and in woe, O Maria! Sign of the Cross The Apostles' Creed I believe in God, the Father almighty, Creator of heaven and earth, and in Jesus Christ, his only Son, our Lord, who was conceived by the Holy Spirit, born of the Virgin Mary, suffered under Ponus Pilate, was crucified, died and was buried; he descended into hell; on the third day he rose again from the dead; he ascended into heaven, and is seated at the right hand of God the Father almighty; from there he will come to judge the living and the dead. -

Twenty-Fourth Sunday in Ordinary Time

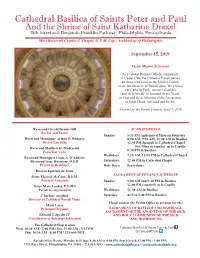

Cathedral Basilica of Saints Peter and Paul And the Shrine of Saint Katharine Drexel 18th Street and Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Most Reverend Charles J. Chaput, O.F.M. Cap., Archbishop of Philadelphia September 15, 2019 Parish Mission Statement As a vibrant Roman Catholic community in Center City, the Cathedral Parish Serves all those who come to the Mother Church of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia. We profess our Catholic Faith, minister to others and welcome all, as founded on the Word of God and the celebration of the Sacraments of Jesus Christ, our Lord and Savior. Adopted by the Parish Council, April 5, 2016 Reverend Gerald Dennis Gill MASS SCHEDULE Rector and Pastor Sunday: 5:15 PM Anticipated Mass on Saturday Reverend Monsignor Arthur E. Rodgers 8:00 AM, 9:30 AM, 11:00 AM in Basilica Rector Emeritus 12:30 PM Spanish in Cathedral Chapel Sta. Misa en español, en la Capilla Reverend Matthew K. Biedrzycki 6:30 PM in Basilica Parochial Vicar Weekdays: 7:15 AM, 12:05 PM in Cathedral Chapel Reverend Monsignor Louis A. D’Addezio Saturdays: 12:05 PM in Cathedral Chapel Reverend Isaac Haywiser, O.S.B. Priests in Residence Holy Days: See website Deacon Epifanio de Jesus SACRAMENT OF PENANCE SCHEDULE Sister Eleanor McCann, R.S.M. Pastoral Associate Sunday: 9:00 AM and 5:30 PM in Basilica 12:00 PM (español) en la Capilla Sister Mary Luchia, P.V.M.I Parish Evangelization Weekdays: 11:30 AM in Basilica Charlene Angelini Saturday: 4:15 to 5:00 PM in Basilica Director of Cathedral Parish Music Please contact the Parish Office to arrange for the: Mark Loria SACRAMENT OF BAPTISM AND MARRIAGE, Principal Organist SACRAMENT OF THE ANOINTING OF THE SICK, Edward J. -

Catholic Reformers

THREE CATHOLIC REFORMERS OF THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY. MARY H. ALLIES. LONDON : BURNS AND OATES. 1878. AT THE FEET OF ST. GREGORY THE SEVENTH, THE PATTERN OF ALL TRUE REFORMERS, I LAY THIS MEMORIAL OF THREE SAINTS, WHO FOLLOWED IN THEIR DAY HIS EXAMPLE, RESTORING THE BEAUTY OF GOD'S HOUSE BY PREACHING THE PENANCE WHICH THEY PRACTISED. PREFACE. The following pages form only a short sketch in the case of each Saint containing some principal incidents in his life, but sufficient, it is hoped, to give a view of the character and actions, so that the reader may draw for himself the lessons to be derived. The authorities followed are, in the case of St. Vincent, the life in the Acta Sanctorum, and of Ranzano, the last written for the Saint's canoniza- tion, which took place about 1456. Also the life by l'Abbe Bayle has been now and then used. In the case of St. Bernardine, the three lives in the Acta Sanctorum, two of which are by eye- witnesses ; the Analecta, collected from various sources, and the Chronica de San Francisco de Assis; with St. Bernardine's own works. In the case of St. John Capistran, the Acta Sanc- torum, containing the learned commentary of the viii Preface, Bollandists three lives three of his ; by companions, eye-witnesses, viz., Nicholas de Fara, Hieronymus de Utino, Christophorus a Varisio. With regard to the title of Apostle, used occa- sionally of these Saints, for which it is believed there is high authority, it must be only taken in a secondary and subordinate sense. -

Improving Coexistence of Large Carnivores and Agriculture in S-Europe

LIFE 04NAT/IT/000144 - COEX IMPROVING COEXISTENCE OF LARGE CARNIVORES AND AGRICULTURE IN S-EUROPE International Symposium Large Carnivores and Agriculture Comparing Experiences across Italy and Europe Assisi, 9-10 March 2007 Proceedings Report Action F4 – LIFE COEX Contents LIST OF PRESENTATIONS ...........................................................................................................................................................2 ABSTRACTS.........................................................................................................................................................................................3 1. EUROPEAN COMMISSION AND LARGE CARNIVORES................................................................................................................3 2. LUPO E AGRICOLTURA, UN EQUILIBRIO REALISTICO................................................................................................................4 3. IL RUOLO DELLE AZIENDE SANITARIE LOCALI (ASL) NELLA GESTIONE DEI GRANDI CARNIVORI....................................4 4. GRANDI CARNIVORI E AGRICOLTURA - ESPERIENZE A CONFRONTO IN ITALIA E EUROPA.................................................5 5. IL CONTRIBUTO DELLA CE PER LA GESTIONE DEI GRANDI CARNIVORI: IL CASO DELLA PROVINCIA DI PERUGIA............6 6. DISSEMINATION O F DAMAGE PREVENTION PRACT ICES FOR SUPPORTING COEXISTENCE: EXPERIENCES IN THE PROVINCE OF TERNI, ITALY..............................................................................................................................................................7 -

Private Higher Education Institutions Faculty-Student Ratio: AY 2017-18

Table 11. Private Higher Education Institutions Faculty-Student Ratio: AY 2017-18 Number of Number of Faculty/ Region Name of Private Higher Education Institution Students Faculty Student Ratio 01 - Ilocos Region The Adelphi College 434 27 1:16 Malasiqui Agno Valley College 565 29 1:19 Asbury College 401 21 1:19 Asiacareer College Foundation 116 16 1:7 Bacarra Medical Center School of Midwifery 24 10 1:2 CICOSAT Colleges 657 41 1:16 Colegio de Dagupan 4,037 72 1:56 Dagupan Colleges Foundation 72 20 1:4 Data Center College of the Philippines of Laoag City 1,280 47 1:27 Divine Word College of Laoag 1,567 91 1:17 Divine Word College of Urdaneta 40 11 1:4 Divine Word College of Vigan 415 49 1:8 The Great Plebeian College 450 42 1:11 Lorma Colleges 2,337 125 1:19 Luna Colleges 1,755 21 1:84 University of Luzon 4,938 180 1:27 Lyceum Northern Luzon 1,271 52 1:24 Mary Help of Christians College Seminary 45 18 1:3 Northern Christian College 541 59 1:9 Northern Luzon Adventist College 480 49 1:10 Northern Philippines College for Maritime, Science and Technology 1,610 47 1:34 Northwestern University 3,332 152 1:22 Osias Educational Foundation 383 15 1:26 Palaris College 271 27 1:10 Page 1 of 65 Number of Number of Faculty/ Region Name of Private Higher Education Institution Students Faculty Student Ratio Panpacific University North Philippines-Urdaneta City 1,842 56 1:33 Pangasinan Merchant Marine Academy 2,356 25 1:94 Perpetual Help College of Pangasinan 642 40 1:16 Polytechnic College of La union 1,101 46 1:24 Philippine College of Science and Technology 1,745 85 1:21 PIMSAT Colleges-Dagupan 1,511 40 1:38 Saint Columban's College 90 11 1:8 Saint Louis College-City of San Fernando 3,385 132 1:26 Saint Mary's College Sta. -

Petrarch and Boccaccio Mimesis

Petrarch and Boccaccio Mimesis Romanische Literaturen der Welt Herausgegeben von Ottmar Ette Band 61 Petrarch and Boccaccio The Unity of Knowledge in the Pre-modern World Edited by Igor Candido An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative and links to the Open Access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. The Open Access book is available at www.degruyter.com. ISBN 978-3-11-042514-7 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-041930-6 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-041958-0 ISSN 0178-7489 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 license. For more information, see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2018 Igor Candido, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Typesetting: Konvertus, Haarlem Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Dedicated to Ronald Witt (1932–2017) Contents Acknowledgments IX Igor Candido Introduction 1 H. Wayne Storey The -

Titles of Mary

Titles of Mary Mary is known by many different titles (Blessed Mother, tion in the Americas and parts of Asia and Africa, e.g. Madonna, Our Lady), epithets (Star of the Sea, Queen via the apparitions at Our Lady of Guadalupe which re- of Heaven, Cause of Our Joy), invocations (Theotokos, sulted in a large number of conversions to Christianity in Panagia, Mother of Mercy) and other names (Our Lady Mexico. of Loreto, Our Lady of Guadalupe). Following the Reformation, as of the 17th century, All of these titles refer to the same individual named the baroque literature on Mary experienced unforeseen Mary, the mother of Jesus Christ (in the New Testament) growth with over 500 pages of Mariological writings and are used variably by Roman Catholics, Eastern Or- during the 17th century alone.[4] During the Age of thodox, Oriental Orthodox, and some Anglicans. (Note: Enlightenment, the emphasis on scientific progress and Mary Magdalene, Mary of Clopas, and Mary Salome are rationalism put Catholic theology and Mariology often different individuals from Mary, mother of Jesus.) on the defensive in the later parts of the 18th century, Many of the titles given to Mary are dogmatic in nature. to the extent that books such as The Glories of Mary (by Other titles are poetic or allegorical and have lesser or no Alphonsus Liguori) were written in defense of Mariology. canonical status, but which form part of popular piety, with varying degrees of acceptance by the clergy. Yet more titles refer to depictions of Mary in the history of 2 Dogmatic titles art. -

St. Stephen Parish

St. Stephen Parish SaintStephenSF.org | 451 Eucalyptus Dr., San Francisco CA 94132 | Church 415 681-2444 StStephenSchoolSF.org | 401 Eucalyptus Dr., San Francisco 94132 | School 415 664-8331 Weekday Mass: 8:00 a.m. Reconciliation: Saturday 3:30 p.m. or by appt. Vigil Mass Saturday 4:30 p.m., Sunday Mass 8:00, 9:30, 11:30 a.m. & 6:45 p.m. May 26 ,2019 Sixth Sunday of Easter How many of us have ever wished, in moments of indecision, that God would send us a clear sign about what we are called to do at that moment – perhaps an angel to tell us exactly what God wants? At times like these, when we’re surrounded by tur- moil and violence, it can be easy to feel that God has left us alone to fend for ourselves – that we’re left on our own with no clear direction. But the readings today, as we come ever nearer to the great Feast of Pentecost, are reassuring. We are not alone, but have God, the Church, and the people around us to give us guidance and support when we need it – as long as we’re open to the different ways the Holy Spirit operates in our daily lives. In the first reading, we see the Church, our brothers and sisters in the faith, as a support system to help us understand what is required of us. The earliest Gentile disciples in Antioch, Syria and Cilicia were misled into believing they had to follow the ancient Mosaic law if they were to be saved – if they were to be Chris- tians. -

Through the Eye of the Dragon: an Examination of the Artistic Patronage of Pope Gregory XIII (1572-1585)

Through the eye of the Dragon: An Examination of the Artistic Patronage of Pope Gregory XIII (1572-1585). Vol.1 Title of Degree: PhD Date of Submission: August 2019 Name: Jacqueline Christine Carey I declare that this thesis has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other University and it is entirely my own work. I agree to deposit this thesis in the University’s open access institutional repository or allow the library to do so on my behalf, subject to Irish Copyright Legislation and Trinity College Library conditions of use and acknowledgement. For Sadie and Lilly Summary This subject of this thesis is the artistic patronage of Pope Gregory XIII (1572-1585). It examines the contribution of the individual patron to his patronage with a view to providing a more intense reading of his artistic programmes. This approach is derived from the individual interests, influences, and ambitions of Gregory XIII. It contrasts with periodization approaches that employ ‘Counter Reformation’ ideas to interpret his patronage. This thesis uses archival materials, contemporaneous primary sources, modern specialist literature, and multi-disciplinary sources in combination with a visual and iconographic analysis of Gregory XIII’s artistic programmes to develop and understanding of its subject. Chapter one examines the efficacy and impact of employing a ‘Counter-Reformation’ approach to interpret Gregory XIII’s artistic patronage. It finds this approach to be too general, ill defined, and reductionist to provide an intense reading of his artistic programmes. Chapter two explores the antecedent influences that determined Gregory XIII’s approach to his papal patronage and an overview of this patronage. -

Dominus Ac Redemptor (1773)

Dominus ac Redemptor (1773) Pope Clement XIV suppressed the Society of Jesus on July 21, 1773. In the preceding decades, the Jesuits had suffered expulsions from the Catholic empires of Portugal (1759), France (1764), and Spain (1767), where they had become handy scapegoats for kings or princes under civic pressure. In Portugal, for example, charges against the Society included creating a state within the state, inciting revolutions among indigenous populations in South America, and failing to adequately condemn regicide. Cardinals in the papal conclave of 1769 elected Giovanni Vincenzo Antonio Ganganelli in part because he had assured the Bourbons that he would suppress the Jesuits, which he did four years later with the papal brief Dominus ac Redemptor. As a result of the expulsions and suppression, hundreds of schools around the globe were closed or transferred to other religious orders or the state; missions closed around the world; and virtually all Jesuits became ex-Jesuits, whether they continued on as priests or as laymen. The Society would not be fully restored until 1814, by Pius VII. For the lasting memory of the action Our Lord and Redeemer Jesus Christ, the Prince of Peace announced by the prophet, when he came into this world first proclaimed peace to the shepherds through the angels. Then before he ascended into heaven, he announced peace through himself. More than once he left the task of peacemaking to his disciples when he had reconciled all things to God the Father. He brought peace through the blood of his cross upon all things that arc on earth or in heaven. -

Lives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors and Architects

Lives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors and Architects Giorgio Vasari Lives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors and Architects Table of Contents Lives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors and Architects.......................................................................1 Giorgio Vasari..........................................................................................................................................2 LIFE OF FILIPPO LIPPI, CALLED FILIPPINO...................................................................................9 BERNARDINO PINTURICCHIO........................................................................................................13 LIFE OF BERNARDINO PINTURICCHIO.........................................................................................14 FRANCESCO FRANCIA.....................................................................................................................17 LIFE OF FRANCESCO FRANCIA......................................................................................................18 PIETRO PERUGINO............................................................................................................................22 LIFE OF PIETRO PERUGINO.............................................................................................................23 VITTORE SCARPACCIA (CARPACCIO), AND OTHER VENETIAN AND LOMBARD PAINTERS...........................................................................................................................................31 -

Order and Disorder the Medieval Franciscans

Order and Disorder The Medieval Franciscans General Editor Steven J. McMichael University of St. Thomas VOLUME 8 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/tmf Order and Disorder The Poor Clares between Foundation and Reform By Bert Roest ᆕ 2013 Cover illustration: Francis of Assisi receiving Clare’s vows. Detail of the so-called Vêture de Sainte Claire (Clothing of Saint Clare) fresco cycle in the baptistery of the cathedral in Aix-en-Provence, created in the context of the foundation of the Poor Clare monastery of Aix by Queen Sancia of Majorca and King Robert of Anjou around 1337. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Roest, Bert, 1965- Order and disorder : the Poor Clares between foundation and reform / by Bert Roest. p. cm. -- (The medieval Franciscans, 1572-6991 ; v. 8) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-24363-7 (alk. paper) -- ISBN 978-90-04-24475-7 (e-book) 1. Poor Clares--History. I. Title. BX4362.R64 1013 271’.973--dc23 2012041307 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. ISSN 1572-6991 ISBN 978-90-04-24363-7 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-24475-7 (e-book) Copyright 2013 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Global Oriental, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers and Martinus Nijhofff Publishers. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher.