Through the Looking Glass: Philosophical Toys and Digital Visual Effects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Optical Machines, Pr

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA UMI800-521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. NOTE TO USERS Copyrighted materials in this document have not been filmed at the request of the author. They are available for consultation at the author’s university library. -

Persistence of Vision: the Value of Invention in Independent Art Animation

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Kinetic Imaging Publications and Presentations Dept. of Kinetic Imaging 2006 Persistence of Vision: The alueV of Invention in Independent Art Animation Pamela Turner Virginia Commonwealth University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/kine_pubs Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, Fine Arts Commons, and the Interdisciplinary Arts and Media Commons Copyright © The Author. Originally presented at Connectivity, The 10th ieB nnial Symposium on Arts and Technology at Connecticut College, March 31, 2006. Downloaded from http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/kine_pubs/3 This Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dept. of Kinetic Imaging at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kinetic Imaging Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Pamela Turner 2220 Newman Road, Richmond VA 23231 Virginia Commonwealth University – School of the Arts 804-222-1699 (home), 804-828-3757 (office) 804-828-1550 (fax) [email protected], www.people.vcu.edu/~ptturner/website Persistence of Vision: The Value of Invention in Independent Art Animation In the practice of art being postmodern has many advantages, the primary one being that the whole gamut of previous art and experience is available as influence and inspiration in a non-linear whole. Music and image can be formed through determined methods introduced and delightfully disseminated by John Cage. Medieval chants can weave their way through hip-hopped top hits or into sound compositions reverberating in an art gallery. -

Proto-Cinematic Narrative in Nineteenth-Century British Fiction

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Fall 12-2016 Moving Words/Motion Pictures: Proto-Cinematic Narrative In Nineteenth-Century British Fiction Kara Marie Manning University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Other Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Manning, Kara Marie, "Moving Words/Motion Pictures: Proto-Cinematic Narrative In Nineteenth-Century British Fiction" (2016). Dissertations. 906. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/906 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MOVING WORDS/MOTION PICTURES: PROTO-CINEMATIC NARRATIVE IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY BRITISH FICTION by Kara Marie Manning A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School and the Department of English at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved: ________________________________________________ Dr. Eric L.Tribunella, Committee Chair Associate Professor, English ________________________________________________ Dr. Monika Gehlawat, Committee Member Associate Professor, English ________________________________________________ Dr. Phillip Gentile, Committee Member Assistant Professor, -

NEKES COLLECTION of OPTICAL DEVICES, PRINTS, and GAMES, 1700-1996, Bulk 1740-1920

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt8x0nf5tp No online items INVENTORY OF THE NEKES COLLECTION OF OPTICAL DEVICES, PRINTS, AND GAMES, 1700-1996, bulk 1740-1920 Finding Aid prepared by Isotta Poggi Getty Research Institute Research Library Special Collections and Visual Resources 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles, CA 90049-1688 Phone: (310) 440-7390 Fax: (310) 440-7780 Email requests: http://www.getty.edu/research/conducting_research/library/reference_form.html URL: http://www.getty.edu/research/conduction_research/library/ ©2007 J. Paul Getty Trust 93.R.118 1 INVENTORY OF THE NEKES COLLECTION OF OPTICAL DEVICES, PRINTS, AND GAMES, 1700-1996, bulk 1740-1920 Accession no. 93.R.118 Finding aid prepared by Isotta Poggi Getty Research Institute Contact Information: Getty Research Institute Research Library Special Collections and Visual Resources 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles, California 90049-1688 Phone: (310) 440-7390 Fax: (310) 440-7780 Email requests: http://www.getty.edu/research/conducting_research/library/reference_form.html URL: http://www.getty.edu/research/conducting_research/library/ Processed by: Isotta Poggi Date Completed: 1998 Encoded by: Aptara ©2007 J. Paul Getty Trust Descriptive Summary Title: Nekes collection of optical devices, prints, and games Dates: 1700-1996 Dates: 1740-1920 Collection number: 93.R.118 Collector: Nekes, Werner Extent: 45 linear feet (75 boxes, 1 flat file folder) Repository: Getty Research Institute Research Libary Special Collections and Visual Resources 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles, CA 90049-1688 Abstract: German filmmaker. The collection charts the nature of visual perception in modern European culture at a time when pre-cinema objects evolved from instruments of natural magic to devices for entertainment. -

Photography and Animation

REFRAMING PHOTOGRAPHY photo and animation PHOTOGRAPHY AND ANIMATION: ANIMATING IMAGES THROUGH OPTICAL TOYS AND OTHER AMUSEMENTS course number: instructor’s name: room number: office number: course day and times: instructor’s email Office Hours: Ex: Tuesdays and Thursdays, 11:45am -1:15pm or email to set up an appointment. COURSE DESCRIPTION Before modern cinema, 19th century optical toys such as the “wonder turner” and the “wheel of the Devil” entertained through the illusion of motion. In this class, you’ll animate still photographic images. You’ll learn to make thaumatropes, flipbooks, and zoetropes, devices that rely upon the persistence of vision, and you’ll create other entertaining objects such as an animated exquisite corpse, tunnel books, strip animations, and moving panoramas. You’ll learn to construct these devices and effectively create an illusion with each. The main focus of the course will be on the development your ideas. COURSE PROJECTS There will be three projects in which you will create an artwork based on a particular early animation device. For these projects, you will create images and build the optical device based on your ideas as an artist. All projects will be evaluated on the strength of your ideas, the inventiveness of your use of the device, the craft of the images and object, and the success of the final illusion. PROJECT 1: flip books PROJECT 2: thaumatropes PROJECT 3: zoetrope COURSE WORKSHOPS There will be five in-class workshops that provide an entry point into experimenting with the larger project, or that allow you to play with other types of devices and illusions. -

SIS Bulletin Issue 28

Scientific Instrument Society Bulletin of the Scientific Instrument Society No. 28 March 1991 Bulletin of the Scientific Instrument Society ISSN 0956-8271 For Table of Contents, see inside back cover Executive Committee Jon Darius, Chairman Gerard Turner, Vice Chairman Howard Dawes, Executive Secretary Stanley Warren, Meetings Secretary Allan Mills, Editor Desmond Squire, Advertising Manager Brian Brass, Treasurer Ronald Bristow Anthony Michaelis Arthur Middleton Stuart Talbot David Weston Membership and Administrative Matters Mr. Howard Dawes P.O. Box 15 Pershore Worcestershire WR10 2RD Tel: 0386-861075 United Kingdom Fax: 0386-861074 See inside back corer for information on membership Editorial Matters Dr. Allan Mills Astronomy Group University of Leicester University Road Leicester LE1 7RH Tel: 0533-523924 United Kingdom Fax: 0533-523918 Advertising Manager Mr Desmond Squire 137 Coombe Lane London SW20 0QY United Kingdom Tel: 081-946 1470 Organization of Meetings Mr Stanley Warren Dept of Archaeological Sciences University of Bradford Richmond Road Tel: 0274-733466 ext 477 Bradford BD7 1DP Fax: 0274-305340 United Kingdom Tel (home): 0274-601434 Typesetting and Printing Halpen Graphic Communication Limited Victoria House Gertrude Street Chelsea London SW10 0]N Tel 071-351 5577 United Kingdom Fax 071-352 7418 Price: £6 per issue, including back numbers where available The Scientific Instrument Society is Registered Charity No. 326733 The Delicate Issue of Short Research Book Reviews Authenticity Projects Sought The Editor would be pleased to hear from Quite recently, for the first time in its Nowadays, students reading for a first members willing to review new and history, the British Museum deliberately deg~ in a scienti~ sub~ct are commmdy forthcoming books in our general fieldof held an exhibition of fakes) Oriented required to carry out a small research interest.If author, titleand publisher(and, towards fine art and statuary, Baird's project in their final year. -

Early Cinema's Touch(Able) Screens – from Uncle Josh to Ali Barbouyou

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Wanda Strauven Early cinema’s touch(able) screens – From Uncle Josh to Ali Barbouyou 2012 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/15054 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Strauven, Wanda: Early cinema’s touch(able) screens – From Uncle Josh to Ali Barbouyou. In: NECSUS. European Journal of Media Studies, Jg. 1 (2012), Nr. 2, S. 155–176. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/15054. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: https://doi.org/10.5117/NECSUS2012.2.STRA Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0 Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 License. For Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF MEDIA STUDIES www.necsus-ejms.org NECSUS Published by: Amsterdam University Press Early cinema’s touch(able) screens From Uncle Josh to Ali Barbouyou Wanda Strauven NECSUS 1 (2):155–176 DOI: 10.5117/NECSUS2012.2.STRA Keywords: cinema, film, tangibility, touchscreen Return of the rube? Last spring a ‘magic moment’ happened at an afternoon screening of Martin Scorsese’s 3D film Hugo (2011). When the end credits were scrolling across the huge screen-wall and the audience was leaving the auditorium, a little girl ran to the front. At first a bit hesitant, she reached up and touched the screen. -

Forms of Machines, Forms of Movement

Forms of Machines, Forms of Movement Benoît Turquety for Hadrien Fac-similes In a documentary produced in 1996-1997, American filmmaker Stan Bra- khage, who spent much of his life painting and scratching film, stated that One of the major things in film is that you have 24 beats in a second, or 16 beats or whatever speed the projector is running at. It is a medium that has a base beat, that is intrinsically baroque. And aesthetically speaking, it’s just appalling to me to try to watch, for example, as I did, Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin on video: it dulls all the rhythm of the editing. Because video looks, in comparison to the sharp, hard clarities of snapping individual frames, and what that produces at the cut, video looks like a pudding, that’s virtually uncuttable, like a jello. It’s all ashake with itself. And furthermore, as a colorist, it doesn’t interest me, because it is whatever color anyone sets their receptor to. It has no fixed color.1 Each optical machine produces a specific mode of perception. Canadian filmmaker Norman McLaren also devoted an essential part of his work to research on the material of film itself, making films with or without camera through all kinds of methods, drawing, painting, scratching film, develop- ing a reflection on what a film frame is and what happens in the interval between two images. Yet today his work is distributed by the National Film Board of Canada only in digital format, and such prestigious institutions as the Centre Pompidou in Paris project it that way – even as the compression of digital files required by their transfer on DVD pretty much abolishes the fundamental cell that is the single frame. -

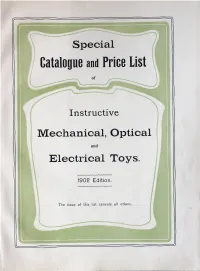

Special Catalogue and Price List of Instructive Mechanical, Optical And

TRADE MARK. 2 Medals Chicago 1893. Gold Medal Gold Medal Nuremberg 1882. Nuremberg 1896. Factory. * tUCj^-sJ ^JC. F actory. — lit rut t if f “ f— . i [vTa* Factory and Warehouse * INSTRUCTIVE * OPTICAL TOYS. Magic Lanterns Dissolving view ffpparati. 5<dopticons. Cinematographs. Large Collection of new slides in sets. Stereoscopes. i.» • JlC >M*\ S" ; o N 1 we made When starting the manufacture of MttgiC LdtertlS a special point of using for this speciality only an excellent and effective Optic. adhered to even in the manufacture of our cheapest This principle, which we have Lanterns, we have to thank, that our goods are not only everywhere appreciated but also find preference to the competition manufacture. Through our continual endeavours we have succeeded in bringing our through a correct Optic Lanterns to a fine state of perfection , and produced. sharp, distinct and large pictures are in Cinematographs we are bringing forth various new sorts this year, which are partly constructed after an entirely new principle. As a special advantage of this new system we might mention the excellent reproduction of living pictures with an almost noiseless working. Our collection of Magic Lantern Slides we have now enlarged, amongst other series, with a new (second set ) of artistic pictures . which like the first serie were sketched and painted by a well known artist. We have also supplemented our collection through a number of other series of slides. y y I he section t(i} £OSCOj)CS etc. has also been enlarged through a number of new patterns, the finish of which is in every respect strong and elegant. -

Dulac and Gaudreault

Dulac and Gaudreault Back to Issue 8 Heads or Tails: The Emergence of a New Cultural Series, from the Phenakisticope to the Cinematograph1 by Nicolas Dulac and André Gaudreault © 2004 This article is part of a larger research project on the different forms attraction has taken in the cultural series animated pictures.2 Here we will focus our attention on the first signs of the paradigm which we propose to call cinématographie-attraction, a paradigm in which the question of thresholds seems to us to be essential.3 Moving picture programs juxtaposed, one after the other, a long string of often disparate views. Viewers of the period, for that very reason, were called upon to enter into a dozen sometimes completely heterogeneous worlds, one after the other, at the same screening.4 The cinématographie-attraction experience was essentially an experience of discontinuity. Full of interruptions and sudden starts, this experience was a chain of shocks, a series of thresholds. The concept of the threshold will be particularly useful here, because it allows us to problematise the various kinds of discontinuity which punctuate the cultural series animated pictures. This punctuation took the form of one of two primary structuring principles running through this series and modulating its development: attraction and narration.5 Our discussion will begin at its emergence with optical toys such as the phenakisticope, the zoetrope, and the praxinoscope. We will attempt to demonstrate the ways in which it might be useful to address the question of cinématographie-attraction by resituating it before the fetish date of 28 December 1895, when tradition tells us it was born. -

The History of the Moving Image Art Lab GRADE: 9-12

The History of the Moving Image Art Lab GRADE: 9-12 STANDARDS The following lesson has been aligned with high school standards but can easily be adapted to lower grades. ART: VA:Cr1.2.IIa: Choose from a range of materials and methods of traditional and contemporary artistic practices to plan works of art and design. SCIENCE: Connections to Nature of Science – Science is a Human Endeavor: Technological Persistence of Vision: refers to the optical illusion advances have influenced the progress of science whereby multiple discrete images blend into a and science has influenced advances in single image in the human mind. The optical technology. phenomenon is believed to be the explanation for motion perception in cinema and animated films. OBJECTIVE Students will be able to explore the influence of MATERIALS advancements of moving imagery by planning and Thaumatrope: creating works of art with both traditional and contemporary methods. • Card stock • String/Dowels • Markers VOCABULARY • Example thaumatrope Zoetrope: a 19th century optical toy consisting of a Flip Book: cylinder with a series of pictures on the inner surface that, when viewed through slits with the • Precut small paper rectangles cylinder rotating, give an impression of continuous • Binder clips motion. • Pencils • Markers Thaumatrope: a popular 19th century toy. A disk • Construction paper with a picture on each side is attached to two • Light table (optional) pieces of string (or a dowel). When the strings are • Example flip book twirled quickly between the fingers the two pictures appear to blend into one due to the persistence of vision. Zoetrope: How has animation and moving image technology changed over time and how has it impacted • 8 in. -

* Omslag Between Stillness PB:DEF

FILM CULTURE IN TRANSITION Between Stillness and Motion FILM, PHOTOGRAPHY, ALGORITHMS EDITED BY EIVIND RØSSAAK Amsterdam University Press Between Stillness and Motion Between Stillness and Motion Film,Photography,Algorithms Edited by Eivind Røssaak The publication of this book is made possible by a grant from the Norwegian Research Council. Front cover illustration: Tobias Rehberger, On Otto, film still (Kim Basinger watching The Lady from Shanghai), . Courtesy Fondazione Prada, Milan Back cover illustration: Still from Gregg Biermann’s Spherical Coordinates () Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam isbn (paperback) isbn (hardcover) e-isbn nur © E. Røssaak / Amsterdam University Press, All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Contents Acknowledgements Introduction The Still/Moving Field: An Introduction Eivind Røssaak Philosophies of Motion The Play between Still and Moving Images: Nineteenth-Century “Philosophical Toys” and Their Discourse Tom Gunning Digital Technics Beyond the “Last Machine”: Thinking Digital Media with Hollis Frampton Mark B.N. Hansen The Use of Freeze and Slide Motion The Figure of Visual Standstill in R.W. Fassbinder’sFilms Christa Blümlinger TheTemporalitiesoftheNarrativeSlideMotionFilm