Saint Peters Episcopal Church Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Our Media Kit Read More

VISIT CARSON CITY MEDIA KIT WHERE HISTORY LIVES AND ADVENTURE AWAITS CARSON CITY The state capital and the centerpoint of a true Nevada experience. Wholesome and wide open, both in our ideals and space to wander. Maybe it’s the pioneering spirit you can feel in the wind or the impressive landscape surrounding us, but there’s something here that allows you to breathe deep and take it all in. Recharging you as you prep for your next adventure. There’s a sense of pride here. It’s shared in friendly nods and in the stories of our history and extends an open invitation to find your Nevada experience in Carson City. ...find your Nevada experience “in Carson City.” visitcarsoncity.biz 2 THE CENTERPOINT OF YOUR TRUE NEVADA EXPERIENCE BUCKLE UP FOR THE RIDE OF YOUR LIFE As the hub of Northern Nevada, Carson City is your launching pad for adventure. After you’ve explored the capital city, use us as your home base to explore the surrounding areas. Whether it’s looking to visit the old-west town of Virginia City, hitting the casinos in Reno, seeing the majestic Sierra Nevada views in Carson Valley, or taking a dip in the crystal-clear waters of Lake Tahoe, Carson City is just 30 minutes away in any direction from big time adventure, history and fun. visitcarsoncity.biz 3 CLOSE TO IT ALL GETTING TO CARSON CITY, NV Carson City is close to it all, less than a 30-minute drive from a Reno-Tahoe International Airport or a beautiful drive from multiple major cities. -

Brief History of Carson City, Heart of Nevada

Brief History of Carson City, Heart of Nevada For nearly 4,000 years before the coming of white settlers, the Washoe Indians occupied the land along the Sierra Nevada Mountain Range that borders Nevada and California. In 1851 a group of prospectors decided to look for gold in the area that is now Carson City. Unsuccessful in that attempt, they opened up a trading post called Eagle Station on the Overland Stagecoach route. It was used by wagon trains of people moving westward. The surrounding area came to be called Eagle Ranch, and the surrounding meadows as Eagle Valley. In time, a number of scattered settlements grew up in the area and the Eagle Ranch became its social center. As a growing number of white settlers came to the area and began to develop the valleys and mountains of the Sierra Nevada, the Washoe people who for so long had occupied the area were overwhelmed. Although lands were allotted to individual Indians by the federal government starting in the 1880s, they did not offer sufficient water. As a result, the Washoe tended to set up camp at the edges of white settlements and ranches in order to work for food. It would not be until the twentieth century that parcels of reservation land were established for them. Many of the earliest settlers in the Carson City area were Mormons led to Eagle Valley by Colonel John Reese. When the Mormons were summoned to Salt Lake City, Utah, by their leader, Brigham Young, many sold their land for a small amount to area resident John Mankin, who later laid claim to the entire Eagle Valley. -

"7- If-II.. I Signature 01 Certifying Offici"! ,/ Dllte I 5 !:!L:Je;

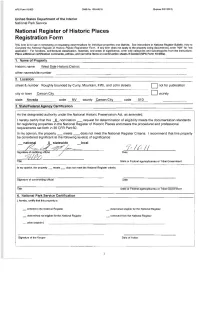

NPS Fom1 11).900 OMB No. 1Q24-OO1B United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form ThilJ form is for use in nominating or re<lue&llng detennlnalfons for 'fldividual properties and disbielS. See InstnJctions in National Regisler Buletin, How to Complme the Nationsl R&I}isler of His/orre Places RegistratIOn FomI. 1f any item does oolappty 10 !he propcrty being documented, .enter "N/A" for ·oot appliC8bfe." For functions, afct'liteetural classification, malerials, and areas of SignifICance, enler orty ~legorie$ and 6ubcategories from the tnstnJctlon3. Place additional certification comments, entries, and nan-ative items on continuation sheets it needed (NPS Fonn10·900aj. 1. Name of Property historic name West Side Historic District other names/site number 2. location street & number Roughly bounded by Curry, Mountain, Fifth, and John streets D not for publication city or town ~C"a"r"-so",n-,-"C,,it,-y______________________ _ o vicinity state Nevada code NV county Carson City code 510 3 State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby eMify thai this ....!... nomination _ requesl for delermination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Hisloric Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set fonh in 36 CFR Part 60_ In my opinion, the propeny _ meels __ does not meet the National Regisler Criteria. I recommend that Ihis property be considered significant at the following levet(s) of significance: _na§. J state~l _local ~ ,c: ______ "7- If-II. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name West Side Historic District other names/site number 2. Location street & number Roughly bounded by Curry, Mountain, Fifth, and John streets not for publication city or town Carson City vicinity state Nevada code NV county Carson City code 510 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property _ meets _ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: national X statewide local ____________________________________ Signature of certifying official Date _____________________________________ Title State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Nevada State Prison NRHP Topo Map New Empire Quadrangle

State Register Number: Property Name: NEVADA DEPARTMENT OF CULTURAL AFFAIRS Rev. 9/2014 STATE HISTORIC PRESERVATION OFFICE 901 S. STEWART STREET CARSON CITY, NEVADA 89701 NEVADA REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic name: Colcord, Gov. Roswell K., House Other names: Bicknell, Charles, House 2. LOCATION Street Address: 700 West Telegraph Street City or Town: Carson City County: Carson City Zip: 89703 Original Location? Yes No. If no, date moved: 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property: private Category of Property: building Number of Resources within Property Buildings 2 Sites _________ Structures _________ Objects _________ Total: ____2_____ 4. CERTIFICATION A. BOARD OF MUSEUMS AND HISTORY As the chair of the Nevada Museums and History Board, I hereby certify that this nomination meets the documentation standards for listing in the Nevada Register of Historic Places. ____________________________________________________________________________________ Signature of the Chair Date B. STATE HISTORIC PRESERVATION OFFICE As the Nevada State Historic Preservation Officer, I hereby certify that this nomination meets the documentation standards for listing in the Nevada Register of Historic Places. ____________________________________________________________________________________ Signature of the State Historic Preservation Officer Date Property Name: Governor Colcord, Roswell K., House State Register Number: 5. FUNCTION OR USE Historic Use: Domestic – Single Dwelling Intermediate Function: Domestic – Single -

Nevada, California & Americana the Library of Clint Maish

Sale 465 Thursday, October 20, 2011 11:00 AM Nevada, California & Americana The Library of Clint Maish with Early Kentucky Documents & additional material Auction Preview Tuesday, October 18, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Wednesday, October 19, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Thursday, October 20, 9:00 am to 11:00 am Other showings by appointment 133 Kearny Street 4th Floor:San Francisco, CA 94108 phone: 415.989.2665 toll free: 1.866.999.7224 fax: 415.989.1664 [email protected]:www.pbagalleries.com REAL-TIME BIDDING AVAILABLE PBA Galleries features Real-Time Bidding for its live auctions. This feature allows Internet Users to bid on items instantaneously, as though they were in the room with the auctioneer. If it is an auction day, you may view the Real-Time Bidder at http://www.pbagalleries.com/ realtimebidder/ . Instructions for its use can be found by following the link at the top of the Real-Time Bidder page. Please note: you will need to be logged in and have a credit card registered with PBA Galleries to access the Real-Time Bidder area. In addition, we continue to provide provisions for Absentee Bidding by email, fax, regular mail, and telephone prior to the auction, as well as live phone bidding during the auction. Please contact PBA Galleries for more information. IMAGES AT WWW.PBAGALLERIES.COM All the items in this catalogue are pictured in the online version of the catalogue at www. pbagalleries.com. Go to Live Auctions, click Browse Catalogues, then click on the link to the Sale. -

Abraham Curry House

Form No. 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Abraham Curry House AND/OR COMMON Abraham Curry House LOCATION STREET & NUMBER 406 North Nevada Street PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Cars on Citv J$4& VICINITY OF 2 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Nevada 32 Carson City 025 S~A3 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC ^—OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X.BUILDINGIS) IL.PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED X_COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _(N PROCESS X-YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED —YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION N/A _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Norman Y. Herring and Stephen Wassner STREET & NUMBER 406 North Nevada Street CITY, TOWN STATE Carson City N/A VICINITY OF Nevada LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETc. Carson City Courthouse STREET & NUMBER Carson Street CITY, TOWN STATE Carson City., Nevada TITLE The Architecture of Carson City, Nevada, Selection from HABS, No. 14. DATE 1972 X—FE °ERAL _STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL Library of Congress CITY, TOWN STATE Washington, B.C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _XEXCELLENT —DETERIORATED 2LUNALTERED X-ORIGINALSITE —GOOD _RUINS _ALTERED —MOVED DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Summary The Abraham Curry House is a single story, symmetrical masonry dwelling supported by a sandstone foundation and terminating in a hip roof. The Vernacular style dwelling, constructed c. -

Historic Kit Carson Trail

2.5 Miles of History found along Carson City’s Historic Kit Carson Trail Considered one of the top attractions in Carson City by the America Automobile Association, the Historic Kit Carson Trail provides a glimpse into the history of this city, known as the true heart of Nevada, for it is in this city the history of Nevada was born and history continues to be made. The West Side Historic District was placed on the National Park Service National Register of Historic Places in 2011 and borders the sections between Mountain Street to the west, Carson Street to the east, Fifth Street to the south and W. Robinson to the north; though, there are some interesting houses found to the north of W. Robinson located a bit out of the walking district. So historic is our city that the National Park Service has designated 44 local sites on their register. Note many of the homes and government buildings were built from the sandstone quarried by prisoners from the Nevada State Prison, built in 1862 and decommissioned in 2012. While the Historic Kit Carson Trail can be accessed at any point, we suggest you begin your historic tour with a visit to the wonderful U.S Mint/Nevada State Museum where you will receive an overview of the uniqueness of this state and Carson City’s contribution to the overall state history. Things to notice along the trail St. Charles/Muller Hotel (cont.) As with most old buildings, this one was in a major At the decree of Carson City founder Abraham Curry, all front doors within the historic district state of disrepair until local citizen Rob McFadden began to rehab it in 1993. -

178-14: Preservation, Development and Use of the Nevada State Prison

178-14 Preservation, Development and Use of the Nevada State Prison Recommendations to: 78th Session – Nevada State Legislature – 2015 Pursuant to AB356 effective July 1, 2013 Prepared by: Nevada State Prison Steering Committee September 2014 Preservation, Development and Use of the Nevada State Prison Recommendations to: 78th Session - Nevada State Legislature – 2015 Prepared by: Nevada State Prison Steering Committee September, 2014 Page i Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................1 Assembly Bill (AB) 356 ...........................................................................................................................1 NSP Steering Committee ........................................................................................................................2 NSP Steering Committee’s Vision ..........................................................................................................2 Museum and Adaptive Reuse ............................................................................................................2 Commercial and Light Industrial .......................................................................................................2 State Functions ....................................................................................................................................2 The Report ...............................................................................................................................................3 -

Women in Nevada History

Revised, Corrected, and Expanded Edition A Digital-Only Document Betty J. Glass 2018 WOMEN IN NEVADA HISTORY An Annotated Bibliography of Published Sources Revised, corrected, and expanded edition Betty J. Glass © 2018 Nevada Women’s History Project Dedicated to the memory of Jean Ford (1929-1998), founder of the Nevada Women’s History Project, whose vision has given due recognition to the role women played and are continuing to play in the history of Nevada. Her tireless leadership and networking abilities made the original project possible. Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................... i Annotated Bibliography ................................................................................................ 1 Index of Nevada Women’s Names ........................................................................... 327 Index of Topics .......................................................................................................... 521 Index of Nevada Women’s Organizations ............................................................... 620 Index of Race, Ethnic Identity of Nevada Women .................................................. 666 Genre Index ............................................................................................................... 672 Introduction This annotated bibliography is a product of the Nevada Women’s History Project (NWHP), a statewide educational Nevada non-profit corporation, 501c3. Our -

The Eagle Street Mint

The Eagle Street Mint – Where Carson City $10 Gold Pieces Began Their Ascent By Tony Arnold #LM-20-0032 The title of my current offering pays homage to Rusty Goe’s The Mint on Carson Street, and to the name given to our favorite capital city’s first permanent settlement circa 85 after Frank Hall shot, stuffed and mounted an eagle over the Eagle Station trading-post door. Quickly sprinting through the years, we traverse through Utah Territory, encounter Mormons, and come to Abe Curry wheeling and dealing with partners and establishing what is now Carson City, Nevada in 858. After the Paiute people were subdued by federal troops and local militia near Pyramid Lake in 860, the Nevada Territory was ready for creation and President James Buchanan signed the legislation on March , 86, just prior to honest Abe Lincoln taking office. Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina was fired upon by Confederate forces on April 12, 86, and the most devastating homeland conflict in United States history began. Father against son, brother against brother to the tune of at least 63,06 military dead and 47,47 wounded. The total casualty figures are the best approximation available using multiple historical sources. It was during the horror of the War Between the States, that the “Battle Born” state of Nevada came into existence on October 3, 864, when President Abraham Lincoln signed the Act of Congress. I now re-introduce my hero Abraham van Santvoord Curry, who from the beginning envisioned Carson City as the state capital complete with a branch mint. -

Abraham Curry, Dr. Anton Tjader, and American Jazz

Abraham Curry, Dr. Anton Tjader, and American Jazz – The Carson City Connection By Michael “The Drummer” Parrott #LM-6-0023 It seems that no matter how much we learn about the history of Carson City, the Comstock, and the “CC” Mint with its fabled coins, there’s always something new just around the corner. In one of my researches I found just such a new tidbit of information; in this case it is an amazing connection between the worlds of pioneer Carson City, Nevada and a more modern world, which I have grown up with: American jazz music. At the outset I must give credit to Doris Cerveri’s fine book, With Curry’s Compliments – The Story of Abraham Curry. I retrieved most of the background information about Curry presented in this article from Cerveri’s book. 7 I’ll begin with Abraham Van Santvoord Curry, hailed as “the Father of Carson City,” who was born on February 19, 1815 in South Trenton, Oneida County, New York. He was the first son of Campbell and Elvira Skinner Curry. At age 0 he married Mary Ann Cowen (age 18), and eventually moved to Portage, Summit County, Ohio. In 1854 he followed Horace Greeley’s advice to “Go West Young Man, Go West,” and along with his young son Charles headed to the gold fields of California. After moving around from San Francisco, Downieville, Red Dog, and other California gold field towns Curry wound up in Eagle Valley, Utah Territory. As just about all of us C4OAers know, Curry, the great man of vision, went on to cofound Carson City in 1858.