Challenges and Options for All-Domain Command and Control for More Information on This Publication, Visit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Textual Analysis of US Army and US Navy Recruiting Advertisements From

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2009 The changing face of the U.S. military: a textual analysis of U.S. Army and U.S. Navy recruiting advertisements from pre-9-11 to six years into the Iraq War Maryann M. Rowland Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Rowland, Maryann M., "The changing face of the U.S. military: a textual analysis of U.S. Army and U.S. Navy recruiting advertisements from pre-9-11 to six years into the Iraq War" (2009). LSU Master's Theses. 1151. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/1151 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CHANGING FACE OF THE U.S. MILITARY: A TEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF U.S. ARMY AND U.S. NAVY RECRUITING ADVERTISEMENTS FROM PRE-9-11 TO SIX YEARS INTO THE IRAQ WAR A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Mass Communication in The Manship School of Mass Communication by Maryann Rowland B.A., University of Central Florida, 2006 May 2009 AKNOWLEDGMENTS The completion of this thesis would not have been possible without the help and support of many people. -

From Representation to Inclusion: Diversity Leadership for the 21St-Century Military

From representation to inclusion: Diversity leadership for the 21st-Century Military Final RepoRt From representation to inclusion: Diversity leadership for the 21st-Century Military Final RepoRt MILITARY LEADERSHIP DIVERSITY COMMISSION 1851 South Bell Street Arlington, VA 22202 March 15, 2011 The Honorable Barack Obama, President of the United States The 112th United States Congress Mr. President and Members of Congress: The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2009 established the Military Leadership Diversity Commission. The Commission was asked to conduct a comprehen- sive evaluation and assessment of policies and practices that shape diversity among mili- tary leaders. Sixteen interrelated tasks, given by Congress, informed the Commission’s enclosed final report, From Representation to Inclusion: Diversity Leadership for the 21st- Century Military. As chairman of this Commission, I am proud to present this report for your consideration. The Commission held itself to high standards of openness and transparency in all deliberations. Moreover, we modeled inclusiveness by inviting those with diverse back- grounds, expertise, and experience to have a say in our independent analysis. The Com- mission sought extensive input for our deliberations from the Department of Defense and the Services as well as the private sector. We hosted 13 public hearings, meeting in loca- tions across the country where many active-duty servicemembers and veterans reside. We heard public testimony from top military leaders, subject matter experts, and diversity officers from leading corporations known for their diversity practices. In addition, we con- ducted interviews with servicemembers. The Commission believes that the diversity of our servicemembers is the unique strength of our military. -

Air Defence in Northern Europe

FINNISH DEFENCE STUDIES AIR DEFENCE IN NORTHERN EUROPE Heikki Nikunen National Defence College Helsinki 1997 Finnish Defence Studies is published under the auspices of the National Defence College, and the contributions reflect the fields of research and teaching of the College. Finnish Defence Studies will occasionally feature documentation on Finnish Security Policy. Views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily imply endorsement by the National Defence College. Editor: Kalevi Ruhala Editorial Assistant: Matti Hongisto Editorial Board: Chairman Prof. Pekka Sivonen, National Defence College Dr. Pauli Järvenpää, Ministry of Defence Col. Erkki Nordberg, Defence Staff Dr., Lt.Col. (ret.) Pekka Visuri, Finnish Institute of International Affairs Dr. Matti Vuorio, Scientific Committee for National Defence Published by NATIONAL DEFENCE COLLEGE P.O. Box 266 FIN - 00171 Helsinki FINLAND FINNISH DEFENCE STUDIES 10 AIR DEFENCE IN NORTHERN EUROPE Heikki Nikunen National Defence College Helsinki 1997 ISBN 951-25-0873-7 ISSN 0788-5571 © Copyright 1997: National Defence College All rights reserved Oy Edita Ab Pasilan pikapaino Helsinki 1997 INTRODUCTION The historical progress of air power has shown a continuous rising trend. Military applications emerged fairly early in the infancy of aviation, in the form of first trials to establish the superiority of the third dimension over the battlefield. Well- known examples include the balloon reconnaissance efforts made in France even before the birth of the aircraft, and it was not long before the first generation of flimsy, underpowered aircraft were being tested in a military environment. The Italians used aircraft for reconnaissance missions at Tripoli in 1910-1912, and the Americans made their first attempts at taking air power to sea as early as 1910-1911. -

GAO-02-914T Military and Veterans' Benefits: Observations on The

United States General Accounting Office GAO Testimony Before the Subcommittee on Benefits, Committee on Veterans’ Affairs, House of Representatives For Release on Delivery Expected at 10:00 a.m. EST, Thursday, July 18, 2002 MILITARY AND VETERANS’ BENEFITS Observations on the Transition Assistance Program Statement of Cynthia A. Bascetta, Director Education, Workforce, and Income Security Issues GAO-02-914T Mr. Chairman and Members of the Subcommittee: Thank you for inviting me to discuss the military’s transition assistance program, which the Congress established in 1990 during a time of military downsizing to help service men and women return to civilian life. Since its inception, the program has served over one million separating and retiring military personnel and has been administered through the coordinated efforts of the Departments of Defense (DOD), Transportation (DOT), Labor (DOL), and Veterans Affairs (VA). In fiscal year 2001, the military branches and DOL spent approximately $47.5 million to provide transition assistance to about 222,000 separating and retiring service members. Today, I will describe the transition assistance offered by each military branch and how their transition assistance programs and services differ. I will also discuss what is known about how well program objectives, such as transitioning to civilian employment, have been met. To conduct our work, we analyzed program descriptions and administrative data from documentation provided by DOD, DOT, DOL, and VA. We also conducted structured group interviews during fieldwork at five locations, one at each military branch—the Army, Air Force, Navy, Marines, and Coast Guard.1 We talked to about 70 service members, including separatees and retirees as well as members expected to separate with a disability, who had participated in the transition assistance workshop. -

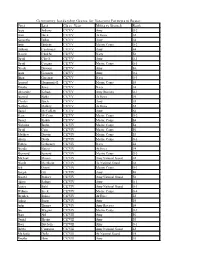

Military Branch Drug DUI Other Property Sex Violence Grand Total

Nevada Department of Corrections Male Population of Veteran Offenders by Offense Group June 30, 2019 1 Military Branch Drug DUI Other Property Sex Violence Grand Total Air Force 4 6 6 5 57 29 107 Army 26 18 17 38 159 130 388 Coast Guard 1 1 1 3 3 9 Marine Corps 6 12 5 22 33 73 151 National Guard 3 1 2 7 16 29 Navy 15 5 3 15 83 62 183 Total Veterans 55 43 31 83 342 313 867 % 6.34% 4.96% 3.58% 9.57% 39.45% 36.10% 100.00% Non Veterans 1,218 321 643 1,667 1,561 4,721 10,131 % 12.02% 3.17% 6.35% 16.45% 15.41% 46.60% 100.00% Unknown 72 9 19 63 255 690 1,108 % 6.50% 0.81% 1.71% 5.69% 23.01% 62.27% 100.00% Grand Total 1,345 373 693 1,813 2,158 5,724 12,106 % 11.11% 3.08% 5.72% 14.98% 17.83% 47.28% 100.00% 1 The military branch category from the most current NDOC prison booking. 2 Source: Nevada Department of Corrections, Offender Management Daily data warehouse. 11/6/2019 NDOC Page 1 Nevada Department of Corrections Male Population of Veteran Offenders by Type of Confinement June 30, 2019 1 2 3 Military Branch Institutional Confinement Other Confinement Total Air Force 107 107 Army 379 9 388 Coast Guard 9 9 Marine Corps 146 5 151 National Guard 28 1 29 Navy 181 2 183 Total Veterans 850 17 867 1 The military branch category from the most current NDOC prison booking. -

The American Army Air Service During World War I's Hundred Days

University of Washington Tacoma UW Tacoma Digital Commons History Undergraduate Theses History Winter 3-12-2020 The American Army Air Service During World War I's Hundred Days Offensive: Looking at Reconnaissance, Bombing and Pursuit Aviation in the Saint-Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne Operations. Duncan Hamlin [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.tacoma.uw.edu/history_theses Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Hamlin, Duncan, "The American Army Air Service During World War I's Hundred Days Offensive: Looking at Reconnaissance, Bombing and Pursuit Aviation in the Saint-Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne Operations." (2020). History Undergraduate Theses. 44. https://digitalcommons.tacoma.uw.edu/history_theses/44 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the History at UW Tacoma Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of UW Tacoma Digital Commons. The American Army Air Service During World War I's Hundred Days Offensive: Looking at Reconnaissance, Bombing and Pursuit Aviation in the Saint-Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne Operations. A Senior Paper Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation Undergraduate History Program of the University of Washington By Duncan Hamlin University of Washington Tacoma 2020 Advisor: Dr. Nicoletta Acknowledgments I would first like to thank Dr. Burghart and Dr. Nicoletta for guiding me along with this project. This has been quite the process for me, as I have never had to write a paper this long and they both provided a plethora of sources, suggestions and answers when I needed them. -

Turkey: Military Service

Country Policy and Information Note Turkey: Military service Version 2.0 September 2018 Preface Purpose This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the basis of claim section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme. It is split into two main sections: (1) analysis of COI; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below. Analysis This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note – i.e. the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw – by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment on whether, in general: x A person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm x A person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies) x A person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory x Claims are likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and x If a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. Decision makers must, however, still consider all claims on an individual basis, taking into account each case’s specific facts. Country of origin information The country information in this note has been carefully selected in accordance with the general principles of COI research as set out in the Common EU [European Union] Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI), dated April 2008, and the Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation’s (ACCORD), Researching Country Origin Information – Training Manual, 2013. -

RECRUITING for DIFFERENCE and DIVERSITY in the U.S. MILITARY by JEREMIAH B. FAVARA a DISSERTATION Presented to the School of J

RECRUITING FOR DIFFERENCE AND DIVERSITY IN THE U.S. MILITARY by JEREMIAH B. FAVARA A DISSERTATION Presented to the School of Journalism and Communication and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2017 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Jeremiah B. Favara Title: Recruiting for Difference and Diversity in the U.S. Military This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the School of Journalism and Communication by: Carol Stabile Chair Gretchen Soderlund Core Member Christopher Chávez Core Member Dan HoSang Core Member CJ Pascoe Institutional Representative and Sara D. Hodges Interim Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded September 2017. ii © 2017 Jeremiah B. Favara iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Jeremiah B. Favara Doctor of Philosophy School of Journalism and Communication September 2017 Title: Recruiting for Difference and Diversity in the U.S. Military After shifting to an all-volunteer force (AVF) in 1973, the U.S. military was forced to expand recruiting efforts beyond the ideal figure of the white male soldier in order to meet personnel needs. Shaped by the economic realities of the AVF, such recruiting efforts sought to show individuals historically excluded from military service, namely women and people of color, that there was a place for them in the military. The presence of women and people of color in recruitment materials contributes to ideals of citizenship and articulates understanding of gender, race, sexuality, and class in relation to military inclusion. -

First Last Class Year Military Branch Rank Community Leadership

Community Leadership Course for Veterans Participant Roster First Last Class Year Military Branch Rank Laura Anthony CLCV V Army O-2 Erinn Black CLCV V Air Force E-5 Samantha Brillon CLCV V Army E-4 Justin Burdette CLCV V Marine Corps O-2 Anthony Canzonieri CLCV V Army E-4 Derrick Clark Sr. CLCV V Navy E-3 David Clay Jr. CLCV V Army O-3 David Coogan CLCV V Marine Corps O-3 Nicole Dawson CLCV V Army E-6 Laura Goossen CLCV V Army O-1 Brian Greenert CLCV V Navy O-3 Leonard Hammonds II CLCV V Marine Corps E-3 Timothy Jones CLCV V Navy E-4 Alexander Kabusk CLCV V Army Reserves O-1 Leonard Kistler CLCV V Air Force E-6 Charles Lynch CLCV V Army E-5 Nathan Mallory CLCV V Air Force E-5 Daniel McCafferty CLCV V Army E-6 Sean McCann CLCV V Marine Corps O-2 Daniel Restivo CLCV V Marine Corps E-4 Nicholas Boyko CLCV IV Marine Corps E-4 David Cain CLCV IV Marine Corps E-6 Matthew Darwin CLCV IV Marine Corps E-3 Adam Davila CLCV IV Marine Corps O-3 Patricia Gerhauser CLCV IV Navy E-4 Brenda Kietzer CLCV IV Air Force E-4 Raymond Leonard CLCV IV Marine Corps O-3 Michael Mason CLCV IV Army National Guard E-5 Nicole McAfoose CLCV IV Air National Guard E-6 Erik Orient CLCV IV Marine Corps O-3 Joseph Ott CLCV IV Army E-8 Shantel Rodney CLCV IV Army National Guard E-6 Adam Salinas CLCV IV Army O-3 Jessica Stahl CLCV IV Army National Guard O-3 William Steele CLCV IV Marine Corps O-4 Brenden Stokes CLCV IV Air Force E-5 Joshua Stuart CLCV IV Army E-5 Justin Thomas CLCV IV Army Reserves E-4 Lee Wagner CLCV IV Marine Corps O-2 Ryan Ahl CLCV III Army E-6 Daniel -

Defence Economic Outlook 2020 Per Olsson, Alma Dahl and Tobias Junerfält

Defence Economic Outlook 2020 Per Olsson, Alma Dahl and Tobias Junerfält Tobias and Dahl Alma Olsson, Per 2020 Outlook Economic Defence Defence Economic Outlook 2020 An Assessment of the Global Power Balance 2010-2030 Per Olsson, Alma Dahl and Tobias Junerfält FOI-R--5048--SE December 2020 Per Olsson, Alma Dahl and Tobias Junerfält Defence Economic Outlook 2020 An Assessment of the Global Power Balance 2010-2030 FOI-R--5048--SE Title Defence Economic Outlook 2020 – An Assessment of the Global Power Balance 2010-2030 Titel Försvarsekonomisk utblick 2020 – En bedömning av den glo- bala maktbalansen 2010-2030 Rapportnr/Report no FOI-R--5048--SE Månad/Month December Utgivningsår/Year 2020 Antal sidor/Pages 86 ISSN 1650-1942 Customer/Kund Ministry of Defence/Försvarsdepartementet Forskningsområde Försvarsekonomi FoT-område Inget FoT-område Projektnr/Project no A112007 Godkänd av/Approved by Malek Finn Khan Ansvarig avdelning Försvarsanalys Bild/Cover: FOI, Per Olsson via Mapchart Detta verk är skyddat enligt lagen (1960:729) om upphovsrätt till litterära och konstnärliga verk, vilket bl.a. innebär att citering är tillåten i enlighet med vad som anges i 22 § i nämnd lag. För att använda verket på ett sätt som inte medges direkt av svensk lag krävs särskild över- enskommelse. This work is protected by the Swedish Act on Copyright in Literary and Artistic Works (1960:729). Citation is permitted in accordance with article 22 in said act. Any form of use that goes beyond what is permitted by Swedish copyright law, requires the written permission of FOI. 2 (86) FOI-R--5048--SE Summary The global military and economic power balance has changed significantly during the past decade. -

F-4 Phantom-Ii Metu & Odtü Teknokent Qatar Armed

VOLUME 14 . ISSUE 98 . YEAR 2020 METU & ODTÜ TEKNOKENT TURKEY’S PIONEER IN UNIVERSITY-INDUSTRY THE STATE OF QATAR AND COOPERATION QATAR ARMED FORCES F-4 PHANTOM-II FLIGHT ROUTE IN TURKEY & WORLD T70 GETTING READY FOR ITS MAIDEN FLIGHT! ISSN 1306 5998 INTERNATIONAL FUTURE SOLDIER CONFERENCE 29-30 SEPTEMBER 2020 Sheraton-Ankara Within the scope of the planned conference program, panels, presentations, and discussions will be held in the following related technology fields: • Combat Clothing, Individual Equipment & Balistic Protection • Weapons, Sensors, Non Lethal Weapons, Ammunition • Power Solutions • Soft Target Protection • Soldier Physical, Mental and Cognitive Performance INTERNATIONAL • Robotics and Autonomous Systems SOLDIECONFERENCE R • Medical FUTURE • C4ISTAR Systems ifscturkey.com • Exoskeleton Technology • CBRN • Logistics Capability organised by supported by supported by supported by in cooperation with Publisher 6 34 Hatice Ayşe EVERS Editor in Chief Ayşe AKALIN [email protected] Managing Editor Cem AKALIN [email protected] International Relations Director Şebnem AKALIN [email protected] Turkey & Qatar Foul-Weather Friends! Editor İbrahim SÜNNETÇİ [email protected] Administrative Coordinator Yeşim BİLGİNOĞLU YÖRÜK [email protected] 48 Correspondent Saffet UYANIK [email protected] A Message from the President F-4 Phantom II Flight Translation of Defense Industries Prof. Route in Turkey & Tanyel AKMAN İsmail DEMİR on the Measures [email protected] Taken Against COVID-19 in World Turkey Editing Mona Melleberg YÜKSELTÜRK Graphics & Design Gülsemin BOLAT Görkem ELMAS [email protected] 12 Photographer Sinan Niyazi KUTSAL Advisory Board (R) Major General Fahir ALTAN (R) Navy Captain Zafer BETONER Prof Dr. -

Army Fires Capabilities for 2025 and Beyond

Army Fires Capabilities for 2025 and Beyond John Gordon IV, Igor Mikolic-Torreira, D. Sean Barnett, Katharina Ley Best, Scott Boston, Dan Madden, Danielle C. Tarraf, Jordan Willcox C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR2124 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-0-8330-9967-9 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2019 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover: Army photo by Spc. Josselyn Fuentes. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface This report documents research and analysis conducted as part of a project entitled Army Fires for Army 2025, sponsored by the Field Artil- lery School at Fort Sill, Oklahoma (a part of the U.S.