The Next Steps Forward for Protecting Australia's Wine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

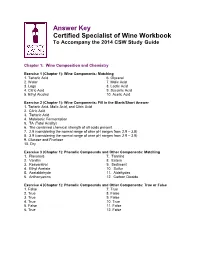

Answer Key Certified Specialist of Wine Workbook to Accompany the 2014 CSW Study Guide

Answer Key Certified Specialist of Wine Workbook To Accompany the 2014 CSW Study Guide Chapter 1: Wine Composition and Chemistry Exercise 1 (Chapter 1): Wine Components: Matching 1. Tartaric Acid 6. Glycerol 2. Water 7. Malic Acid 3. Legs 8. Lactic Acid 4. Citric Acid 9. Succinic Acid 5. Ethyl Alcohol 10. Acetic Acid Exercise 2 (Chapter 1): Wine Components: Fill in the Blank/Short Answer 1. Tartaric Acid, Malic Acid, and Citric Acid 2. Citric Acid 3. Tartaric Acid 4. Malolactic Fermentation 5. TA (Total Acidity) 6. The combined chemical strength of all acids present. 7. 2.9 (considering the normal range of wine pH ranges from 2.9 – 3.9) 8. 3.9 (considering the normal range of wine pH ranges from 2.9 – 3.9) 9. Glucose and Fructose 10. Dry Exercise 3 (Chapter 1): Phenolic Compounds and Other Components: Matching 1. Flavonols 7. Tannins 2. Vanillin 8. Esters 3. Resveratrol 9. Sediment 4. Ethyl Acetate 10. Sulfur 5. Acetaldehyde 11. Aldehydes 6. Anthocyanins 12. Carbon Dioxide Exercise 4 (Chapter 1): Phenolic Compounds and Other Components: True or False 1. False 7. True 2. True 8. False 3. True 9. False 4. True 10. True 5. False 11. False 6. True 12. False Exercise 5: Checkpoint Quiz – Chapter 1 1. C 6. C 2. B 7. B 3. D 8. A 4. C 9. D 5. A 10. C Chapter 2: Wine Faults Exercise 1 (Chapter 2): Wine Faults: Matching 1. Bacteria 6. Bacteria 2. Yeast 7. Bacteria 3. Oxidation 8. Oxidation 4. Sulfur Compounds 9. Yeast 5. -

Current Wine List

Accessories - Wine BARFLY 24oz Mixing Glass 39.99 DeLaurenti Wine & Beer BARFLY Bar Spoon 19.99 Inventory BARFLY Boston Shaker Set 29.99 BARFLY Hawthorne Strainer 21.99 Last updated: BARFLY JapaneseStyleJigger 14.99 4/23/2021 BARFLY Wooden Muddler 16.99 DELAURENTI Wine Key 9.99 Inquire within re: RIEDEL Decanter 199.99 Special Orders TRUE Champagne Stopper 6.99 Out of State Shipping African Wine Quantity Discounts TESTALONGA Orange Skin 750ml 41.99 [email protected] TESTALONGA White Cortez 750ml 39.99 (206) 622-0141 ext. 3 TESTALONGA WishWasANinjaPetnat 27.99 Aperetif ATXA Vermouth Red 18.99 Submit requests from BORDIGA Vermouth Bianco 42.99 this list in the comments BRAVO Vermut del Sol 750ml 24.99 field at check out BYRRH Grand Quinquina 19.99 CAPERITIF 750ml 31.99 CAPPELLETTI Aperitivo 19.99 CARDAMARO Vino Amaro 24.99 CARPANO Antica Formula 1ltr 39.99 CINZANO Extra Dry Vermouth 10.99 CINZANO Rosso Vermouth 13.99 COCCHI Americano Rossa 21.99 COCCHI Americano Rossa 375ml 13.99 COCCHI Vermouth di Torino 375 13.99 CONTRATTO Americano 24.99 CONTRATTO Rosso Vermouth 24.99 DOLIN Vermouth Blanc 15.99 DOLIN Vermouth Dry 15.99 DOLIN Vermouth Rouge 15.99 FRED JERBIS Vermouth 750ml 44.99 LILLET Red 26.99 LILLET Rose 26.99 LILLET White 26.99 MANCINO Vermouth Chinato 500ml 41.99 MANCINO Vermouth Rosso 38.99 MANCINO Vermouth Rosso Vecchio 189.99 MANCINO Vermouth Sakura 500ml 48.99 MANCINO Vermouth Secco 38.99 MATTEI Corse Cap Blanc 21.99 MATTEI Corse Cap Rouge 21.99 REGAL ROGUE Bold Red 29.99 REGAL ROGUE Daring Dry 24.99 REGAL ROGUE Lively White -

When Malbec Became Argentine: an Analysis of the Quality Wine Revolution in Mendoza Dominique Lee

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2018 When Malbec became Argentine: An Analysis of the Quality Wine Revolution in Mendoza Dominique Lee Recommended Citation Lee, Dominique, "When Malbec became Argentine: An Analysis of the Quality Wine Revolution in Mendoza" (2018). Scripps Senior Theses. 1224. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/1224 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHEN MALBEC BECAME ARGENTINE: AN ANALYSIS OF THE QUALITY WINE REVOLUTION IN MENDOZA by DOMINIQUE LEE SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS PROFESSOR GABRIELA MORALES, SCRIPPS COLLEGE PROFESSOR BRIAN KEELEY, PITZER COLLEGE APRIL 12th, 2018 Lee 2 Table Contents Abstract 4 1.0 Why Study Wine? 5 1.0.1 Quality Versus Quantity 7 1.1 Methodology 9 1.2 An Introduction to Terroir 11 2. History of Winemaking in Argentina 14 2.1 Government Regulation: A Precursor to Change 15 2.1.1 Argentina’s Turbulent Economy 16 2.2 Was there a Revolution in Argentinian Wine Production? 17 2.2.1 Thomas Kuhn’s Paradigm Shifts 18 2.3 Paradigm Shift in Mendoza Wine Production 22 2.3.1 The Previous Paradigm: Prior to the 1990s 23 2.3.2 The Paradigm Shift 26 2.3.3 The New Paradigm 28 2.4 Conversion Between Paradigms 30 2.5 What is Progress within Paradigms? 31 2.6 Beginning of Geographic Indication Systems 34 3. -

Regal Riesling Extends Its Reign

Regal riesling extends its reign 274_Part_A_Front.indd 34 9/12/2015 9:11:05 AM DAN TRAUCKI UNTIL fairly recently riesling was synonymous with being lots of talk of a “chardonnay revival”, in vintage has been growing not only in size but also in German wine. It is the noble grape variety that for 2015, riesling prices in South Australia exceeded the relevance to the riesling world. As chairman, Helm hundreds of years made the best of, as well as most prices of chardonnay in every region in which both says: “This is not just another wine show, it is an event of, Germany’s white wine. These wines were mainly varieties are grown. to promote riesling from the vineyard through to the low in alcohol, around 8-11 per cent and in most The second part of the riesling story starts in 2000, consumer. Imparting knowledge about riesling is cases anywhere from slightly sweet through to the when respected Canberra winemaker, Ken Helm AM, the essence of the event. Our aim is to be the world amazingly sweet trockenbeerenauslese style. Only created the Canberra Riesling Challenge in order to centre for communicating riesling knowledge”. In a small proportion was dry (kabinet) in style. benchmark and promote rieslings from across the keeping with this theme, the organisers announced The winds of change started as a zephyr in 1953, nation. The aim being to improve the quality and that from 2015 onwards, one of the masterclasses when under the inspired leadership of Colin Gramp appreciation of Australian riesling. In the same year conducted as part of the CIRC would feature a AM, Orlando Wines made the first modern white wine Clare Valley winemakers unanimously adopted the riesling growing region of the world. -

Information About Australia Can Increase the Choice of Australian Wines by Chinese Consumers

CHINA BUSINESS & MARKETING Thinking outside the bottle: information about Australia can increase the choice of Australian wines by Chinese consumers By Patricia Osidacz Williamson1, Simone Mueller Loose2, Larry Lockshin2 and Leigh Francis1 1The Australian Wine Research Institute, PO Box 197, Glen Osmond, South Australia 5064 2Ehrenberg-Bass Institute for Marketing Science, University of South Australia ____ Many Australian wine producers are targeting China as a new market. With a population of more than 1.3 billion and a growing middle class, the potential for wine sales in China is huge. However, cultural differences and competition from other wine-producing countries are all barriers to be overcome. Research on wine consumer behaviour in China, including the factors that influence choice of Australian wines, can assist Australian wine producers in their efforts to break into this important market. HOW DO CONSUMERS CHOOSE WINES? AT A GLANCE: or most wine consumers, wine • Online experiments were used to investigate the factors influencing wine is one of the products that purchase decisions by Chinese consumers Fadd enjoyment to life. A social • Exposure to short articles about Australia increased the choice of Australian dinner with a glass of wine is a wines by Chinese consumers pleasurable occasion, and the flavour • All articles about Australia were effective in increasing choice of Australian of a particular wine can contribute wines, but the most effective were messages that Chinese people like the taste of to the occasion. Apart from the taste Australian wines and that Australian produce is clean and unpolluted of the wine, there are other factors • The influence of the articles about Australia was shown to persist when that can influence the satisfaction consumers were re-tested after more than a week. -

SPARKLING WINE in the AUSTRALIAN MARKET Report

Report Brochure SPARKLING WINE IN THE AUSTRALIAN MARKET OCTOBER 2015 REPORT PRICE • GBP 1,500 • AUD 3,300 • USD 2,400 • EUR 2,100 • 3 Report Credits © Wine Intelligence 2015 1 Report price Report price: GBP 1,500 USD 2,400 EUR 2,100 AUD 3,300 Report credits: 3 52 page PowerPoint report *All prices exclusive of VAT, GST, or relevant local sale taxes at the current rate 2 Contents page 1. Introduction p.4 5. Sparkling wine consumers trend and profiling p.23 2. Sparkling wine market context p.6 . Frequency of sparkling wine consumption . Market size . Sparkling wine types consumption reach . Per capita consumption of sparkling wine . Frequency of sparkling wine consumption by type . Australia sparkling wine volumes . Gender and age distribution of drinkers by sparkling wine type . Portraits of drinkers by type of sparkling wine . Crossover and consumption between different sparkling wine 3. Management summary p.9 types . Management summary . Sparkling wine + Italian Prosecco and Cava drinkers profile . Sparkling wine drinkers profiling . Key takeaways 4. Sparkling wine vs other alcoholic 6. Sparkling wine brand health p.36 beverages p.12 . Brand power . Alcoholic beverage repertoire . Brand awareness . Preferred beverage by occasion . Brand purchase . Imagery associations for alcoholic beverage categories . Most frequently purchased brands . Gender and age distribution amongst all alcohol drinkers . Brand conversion . Key takeaways . Brand recommendation . Profiling of top 10 sparkling brands . Key takeaways 7. Appendix p.46 . Portraits segmentation overview . Methodology 3 Excerpts from the introduction “Australia is the world’s 10th largest sparkling wine market by volume. It’s an impressive ranking for a small population. -

New Zealand Winegrowers Annual Report 2014 Our Vision

HE WORLD, ND T NEW OU ZE AR AL • A S ND E IN IS R W E L N A O N W IO N T E P D E C F X O E R S I T T I S R E O X F C E D P E T N I O W N O A N L E W R I S N I E D S N • A A L R A O E U Z N W D E T N H , E D L W R O O R W L D E , H N T E D W N Z U E O A R L A A • N S D E I N S I R W E L N A O N W O I N T E P D E F C O X E R S I T NEW ZEALAND WINEGROWERS ANNUAL REPORT 2014 OUR VISION AROUND THE WORLD, NEW ZEALAND IS RENOWNED FOR ITS EXCEPTIONAL WINES OUR MISSION TO CREATE VALUE FOR OUR MEMBERS OUR PURPOSE TO PROTECT THE COMPETITIVE POSITION OF WINE FROM NZ TO SUPPORT THE PROFITABLE GROWTH OF WINE FROM NZ OUR ACTIVITIES ADVOCACy / RESEARCh / SUSTAINABILITY / MARKETING CONTENTS NEW ZEALAND WINEGROWERS ANNUAL REPORT 2014 2 CHAIRS’ REPORt 14 SuSTAINABILITY 30 INDUSTRY BOARDs 6 2014 REPORT CARd 16 MARKETINg 31 INDUSTRY ORGANISATIONS 17 List of visitors to New Zealand 7 BIOSECURITY POSTER 19 User pays events summary 32 NEW ZEALAND 2013/2014 wINEGROWERS’ kEY 8 ADVOCAcy CONTACTS 20 WINE AwARDs 10 RESEARCh 20 Air New Zealand Wine Awards 2013 11 Key initiatives and results 20 Bragato Wine Awards trophy 12 Projects funded, research results 2013 reports, articles, fact sheets published over 2013/2014 21 STATISTICS 13 INFORMATION 21 New Zealand wine industry RESOURCES key performance indicators 22 Summary: 13 Surveys, publications and New Zealand wine reports 23 New Zealand Winegrowers membership 24 New Zealand producing vineyard area 25 New Zealand vintages 26 New Zealand wine exports by market 28 New Zealand wine exports by variety 29 Wine imports into New Zealand CHAIRs’ REPORT WE ARE ALL WINEGROWERS of 2012. -

Cabernet Sauvignon and Blends

CABERNET SAUVIGNON AND BLENDS EDUCATOR GUIDE AUSTRALIAN WINE DISCOVERED PREPARING FOR YOUR CLASS THE MATERIALS VIDEOS As an educator, you have access to a suite of teaching resources and handouts, You will find complementary video including this educator guide: files for each program in the Wine Australia Assets Gallery. EDUCATOR GUIDE We recommend downloading these This guide gives you detailed topic videos to your computer before your information, as well as tips on how to best event. Look for the video icon for facilitate your class and tasting. It’s a guide recommended viewing times. only – you can tailor what you teach to Loop videos suit your audience and time allocation. These videos are designed to be To give you more flexibility, the following played in the background as you optional sections are flagged throughout welcome people into your class, this document: during a break, or during an event. There is no speaking, just background ADVANCED music. Music can be played aloud, NOTES or turned to mute. Loop videos should Optional teaching sections covering be played in ‘loop’ or ‘repeat’ mode, more complex material. which means they play continuously until you press stop. This is typically an easily-adjustable setting in your chosen media player. COMPLEMENTARY READING Feature videos These videos provide topical insights Optional stories that add from Australian winemakers, experts background and colour to the topic. and other. Feature videos should be played while your class is seated, with the sound turned on and clearly SUGGESTED audible. DISCUSSION POINTS To encourage interaction, we’ve included some optional discussion points you may like to raise with your class. -

Varietal Thiols and Green Characters

The Australian Wine Research Institute Varietal Thiols and Green Characters Natoiya Lloyd [email protected] Compounds responsible for the The Australian Wine green character Research Institute Methoxypyrazines N OMe . IBMP, SBMP, IPMP N Sulfur compounds 3-Isobutyl-2-methoxypyrazine . DMS, DES, DMDS (IBMP) . 2-Isobutylthiazole S C6 compounds Dimethyl sulfide . (Z)-3-Hexen-1-ol (DMS) . (E)-2-Hexenal . (Z)-3-Hexenal OH . Hexanal . 1-Hexanol (Z)-3-Hexen-1-ol . Hexyl esters (cis-3-Hexen-1-ol) Grape sources of C6 flavours in wine The Australian Wine Research Institute cis-3-Hexen-1-ol precursors . Formed from unsaturated fatty acids after berry damage (usually upon crushing) . Derived from linolenic acid through enzyme cascade O HO LOX/HPL O ADH OH Linolenic Acid (Z)-3-Hexenal (Z)-3-Hexen-1-ol Lipoxygenase → hydroperoxide lyase → alcohol dehydrogenase The Australian Wine Modulating factors – cis-3-Hexen-1-ol Research Institute Viticulture OH (Z)-3-Hexen-1-ol . Enzymatic formation via LOX pathway leads to C6 compounds (cis-3-Hexen-1-ol) . Differs between varieties and during berry development (e.g. Riesling vs Cabernet Sauvignon) . Highest at pre-veraison in line with unsaturated fatty acid levels – decline in linolenic acid with ripening . Higher in skin (from press cake) than must at all ripening stages The Australian Wine Modulating factors – cis-3-Hexen-1-ol Research Institute OH Winemaking (Z)-3-Hexen-1-ol (cis-3-Hexen-1-ol) . Time and temperature of skin contact – similar extraction from 15-28 oC with max after 10-15 h, continual increase during contact time at 10 oC after 25 h . -

Australia's Sparkling Wines

AUSTRALIA’S SPARKLING WINES AUSTRALIAN WINE DISCOVERED YOUR NOTES TO DAY - The history and rise of sparkling wine in Australia Australia’s unique climate and landscape have fostered a fiercely WE’LL - How sparking wine independent wine scene, home is made to a vibrant community of growers, - Sparkling wine styles winemakers, viticulturists, and vignerons. With more than 100 - Australia’s sparkling grape varieties grown across 65 wine regions distinct wine regions, we have the - Drinking and enjoying freedom to make exceptional wine, and to do it our own way. We’re not sparkling wine beholden by tradition, but continue - Australian sparkling to push the boundaries in the pursuit COVER… wine by numbers of the most diverse, thrilling wines in the world. That’s just our way. Notes Notes HISTORY AND RISE OF SPARKLING 1930s 1980s Cool-climate, high-quality WINE IN AUSTRALIA & ’40s sparkling reds make a 1893 comeback, while Champagne Preece produces iconic and sparkling wine producer Winemaker Edmund sparkling reds that Mazure begins using Moët & Chandon settles in the winemakers still try to Yarra Valley to make Australian Shiraz grapes to produce emulate today. sparklings. Australian sparkling reds in South Australia. 1881 1918 The Victorian Champagne Hans Irvine retires; 1950s TO DAY Company produces its first Seppelts takes over Great Sparkling Burgundy. Western winery, with Colin Sparkling wine gains Australian sparklings are Preece as winemaker. momentum as a trendy, shining brighter than ever. celebratory drink. Notes Notes H O W AUSTRALIAN SPARKLING Predominant sparkling wine grapes METHODS FOR WINE IS – Chardonnay – Traditional method (méthode traditionnelle) – Pinot Noir PRODUCING – Transfer method – Pinot Meunier – Ancestral method (méthode ancestrale) MADE SPARKLING – Tank method WINE – Carbonation Notes Notes TRADITIONAL METHOD TRANSFER METHOD (MÉTHODE TRADITIONNELLE) 1. -

New Outlook in Viticulture and the Impact on Wine Quality April 29, 2014 April

21 APRIL 29, 2014 MENDOZA, ARGENTINA THE IMPACT ON WINE QUALITY THE IMPACT NEW OUTLOOK IN VITICULTURE AND IN VITICULTURE NEW OUTLOOK Cover design: Bruno Loste E WIN IN TION A T FERMEN CTIC A L O L MA NEW OUTLOOK IN VITICULTURE AND THE IMPACT ON WINE QUALITY APRIL 29, 2014 MENDOZA, ARGENTINA 21 MENDOZA, ARGENTINA, APRIL 29, 2014 NEW OUTLOOK IN VITICULTURE AND THE IMPACT ON WINE QUALITY PROCEEDINGS OF THE XXVes ENTRETIENS SCIENTIFIQUES LALLEMAND FOREWORD t the XXVes Entretiens Scientifiques Lallemand, Aromas y Sabores DICTUC in Chile, presented work fo- viticulture experts updated attendees on cur- cused on the other end of the wine spectrum – key aroma Arent knowledge in viticulture science. The ses- compounds and how they affect consumer preferences. sion opened with Alain Deloire from the National Wine In but one example, he discussed how thiols, which are and Grape Industry Centre of Charles Sturt University in influenced by viticultural practices and other factors, are Wagga Wagga, Australia, who discussed the complexity rated by consumers and orient their choices. of fruit composition, including its impact on wine style Fernando Zamora from Universitat Rovira I Virgili in and consumer preferences. He also discussed vine physi- Spain began his presentation by describing the changes ology and the genetic factors influencing grape quality. to anthocyanin and tannin concentrations in red grapes His introduction to the topic of viticulture gave a great throughout ripening. He then explained the various meth- overview of this very complex science. Jorge Perez Peña, ods that exist for determining phenolic maturity (e.g., from INTA EEA Mendoza, gave an excellent talk on Ar- Glories, ITV, AWRI, Cromoenos, etc.), stating the pros and gentinean viticulture and the many challenges faced by cons of each. -

2018 PORTRAIT EDEN VALLEY DRY RIESLING Our Portrait Wines Are the Perfect Introduction to the Renowned Barossa Varietals and Their Classic Styles

FAITHFUL TO TASTE, NOT CONVENTION SINCE 1979. 2018 PORTRAIT EDEN VALLEY DRY RIESLING Our Portrait wines are the perfect introduction to the renowned Barossa varietals and their classic styles. The wines are crafted to represent our ‘Portrait’ of what a Barossan Shiraz, Cabernet Sauvignon, Riesling or Grenache Rosé should taste like. Our Portrait wines keep the promise Peter made to growers across the region to always make wines that showcase the true character of the Barossa. They are a nod to the collective heritage and individual capabilities of the people, vineyards and vines of the Barossa, the whole Barossa wine community. This Eden Valley Riesling is zesty, clean and refreshing when young, then matures to become softer and honeyed with age. The delicate green/gold colour of the wine leads to an enticing aroma of freshly picked green apples and limes with hints of citrus blossom. The wine displays vibrant lime Winemaker’s note juice characters with some minerality typical of a quality Eden Valley Riesling. The palate is elegant with a crisp, dry finish. Delicious in its youth, it lends itself to drinking upon release but can also benefit from up to ten years cellaring. Nigel Westblade, Chief Winemaker After reasonable winter and spring rainfall, soil moisture was adequate during the growing season and Eden Valley vineyards exhibited healthy canopies heading into summer. January and February were warm and dry, with very Vintage warm temperatures in February slowing down the pace of ripening. This resulted in refined and elegant Riesling with beautiful natural acidity. The 2018 vintage in Eden Valley will be one to savour.