1 OVERCOMING a SENSE of ACADEMIC FAILURE Sue Blackmore, the Way This Is Part of an Initiative Designed to Help Make It OK To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mastermind and Celebrity Mastermind Invitation to Tender

BBC’s Mastermind and Celebrity Mastermind Invitation To Tender (ITT) 10 September 2018 Production of Mastermind and Celebrity Mastermind Contract for 2 years commencing with delivery in July 2019 ITT SUMMARY1 The BBC is inviting producers to tender for the production of Mastermind and Celebrity Mastermind. Mastermind and Celebrity Mastermind are long-running, successful BBC series at the heart of the BBC Two and BBC One schedules. The contract to produce Mastermind and Celebrity Mastermind is offered on a work-for-hire basis and all IP remains with the BBC. The contract, including 31 episodes of Mastermind and 10 episodes of Celebrity Mastermind per year, is for 2 years commencing with delivery in July 2019. John Humphrys will continue to present both shows. The current tariff for Mastermind and Celebrity Mastermind is an average of £36,0412 per episode or £2,955,362 for both series across the 2 years, funded by the BBC public service. The Production must remain Out of London, with a preference for one of the BBC’s centres for quiz content in Salford, Scotland or Northern Ireland. Schedule of key stages* ITT Published 10 September 2018 Tender eligibility closes 21 September 2018 Longlist notified 5 October 2018 Face to face meeting 19 October 2018 Tender submissions 14 November 2018 Shortlist notified 3 December 2018 Interviews 17 December 2018 TUPE Conversations 10 January 2019 Award decision announced 14 February 2019 Transmission from August 2019 * all dates are subject to change and Tenderers will be notified of any changes Tender eligibility Producers bidding on their own or in partnership will be considered. -

LOO 2015 — Dick in a Seasonal Box Packet 3B Written by Pericardium and David Knapp Edited by David Knapp

LOO 2015 | Dick in a seasonal box Packet 3b Written by Pericardium and David Knapp Edited by David Knapp 1. This character lives in the suburbs of London with twin sister Mimmy, and parents George and Mary, who bakes the best apple pie in the neighbourhood. She has a cat called Charmmy and a seal called Mori. This character's motto is \you can never have too many friends". She first appeared in 1974 on a purse and can now be found on over 50,000 product lines which make huge sums for the Japanese Sanrio corporation. Resembling a white Japanese bobtail cat with a colourful bow, for ten points, name this anthropomorphic fictional character whose name follows the word \Hello". ANSWER: Kitty [accept Hello Kitty] 2. This man cries \the power of Christ compels you" when he loses control of his rotating chair. One scheme created by this man was named the \Alan Parsons Project" and he possesses a bald cat named Mr. Bigglesworth. This man was separated from his twin brother as a toddler and raised by Belgians, which resulted in his malevolence, and he was reconciled with his son after the latter presented him with sharks with laser beams on their heads. This man hires an obese Scotsman to steal the mojo of his enemy, and he creates a clone of himself called Mini-Me. For ten points, name this nemesis of Austin Powers. ANSWER: Dr. Evil [or Dougie Powers] 3.This former Oakland Raiders linebacker's acting credits include an appearance in the video to Michael Jackson's \Liberian Girl" as well as a brief appearance in Close Encounters of the Third Kind. -

Lauren Layfield

Lauren Layfield Lauren Layfield is a British Guyanese TV and radio broadcaster, with a range of experience across live, factual and comedy shows. In early 2020, Lauren was announced as the new solo host of the BAFTA-winning programme ‘The Dog Ate My Homework’, previously fronted by ITV2 comedian Iain Stirling. Filming of the CBBC comedy panel show is scheduled for later this year. She is the host of Capital’s 'Early Breakfast' slot, live from 4am to 6am on weekdays and is the cover presenter for ‘The Capital Breakfast Show with Roman Kemp’. Lauren is an accomplished live television presenter thanks to four years of weekday afternoons presenting live continuity on ‘CBBC HQ’. She was the host of design programme ‘The Dengineers’ which won the BAFTA for Best Factual Entertainment in 2019 and she currently presents ‘The Playlist’ where she interviews the biggest names in pop, as well as appearing as a guest on countless other CBBC shows. In sport, you may have seen her presenting for BBC One’s ‘Match of the Day’ and its youth-oriented spin-off ‘MOTDx’ on BBC Two. She has hosted for the Premier League, Gfinity’s FIFA Elite Series and she’s a Manchester City fan. Lauren’s career started in journalism working as a reporter, which saw her wearing stab vests on 4am police raids, interviewing sex workers and joining protestors at a nuclear power station. This unique background made her the perfect choice for Channel 4’s ‘Hollyoaks’ podcast, which takes issues raised in the soap and delves into the stories and people behind them, from far-right extremism to drag culture. -

TUESDAY 19TH FEBRUARY 06:00 Breakfast 09:15 Countryfile Winter

TUESDAY 19TH FEBRUARY All programme timings UK 06:00 Good Morning Britain All programme timings UK All programme timings UK 06:00 Breakfast 08:30 Lorraine 09:50 Combat Ships 06:00 Forces News Replay 09:15 Countryfile Winter Diaries 09:25 The Jeremy Kyle Show 10:40 The Yorkshire Vet Casebook 06:30 The Forces Sports Show 10:00 Homes Under the Hammer 10:30 This Morning 11:30 Nightmare Tenants, Slum Landlords 07:00 Battle of Britain 11:00 Wanted Down Under Revisited 12:30 Loose Women 12:20 Counting Cars 08:00 Battle of Britain 11:45 Claimed and Shamed 13:30 ITV Lunchtime News 12:45 The Mentalist 09:00 Never The Twain 12:15 Bargain Hunt 13:55 Regional News and Weather 13:30 The Middle 09:30 Never The Twain 13:00 BBC News at One 14:00 James Martin's Great British Adventure 13:50 The Fresh Prince of Bel Air 09:55 Hogan's Heroes 13:30 BBC London News 15:00 Tenable 14:15 Malcolm in the Middle 10:30 Hogan's Heroes 13:45 Doctors 14:40 Scrubs 11:00 Hogan's Heroes 14:10 A Place to Call Home 15:05 Shipwrecked 11:30 Hogan's Heroes 15:00 Escape to the Country 15:55 MacGyver 12:00 RATED: Games and Movies 15:45 The Best House in Town 16:45 NCIS: Los Angeles 12:30 Forces News 16:30 Flog It! 17:30 Forces News 13:00 Battle of Britain 17:15 Pointless 18:00 Hollyoaks 14:00 Battle of Britain 18:00 BBC News at Six 18:25 Last Man Standing 15:00 R Lee Ermey's Mail Call 18:30 BBC London News 18:50 How to Lose Weight Well 15:30 R Lee Ermey's Mail Call 19:00 The One Show 19:45 Police Interceptors 16:00 The Aviators 19:30 EastEnders 20:35 The Legend of Tarzan 16:30 The Aviators The residents of Walford pay their final 22:20 Mad Max Fury Road 17:00 RATED: Games and Movies respects to Doctor Legg. -

Rhys James Comedian / Writer / Actor

Rhys James Comedian / Writer / Actor Rhys James is an accomplished comedian, writer and actor who you will have seen on ‘Roast Battle’ (Comedy Central), ‘Russell Howard’s Stand Up Central’ (Comedy Central), ‘A League of Their Own’ (Sky One) and ‘Live At The Apollo’ (BBC Two) and as a regular panellist on ‘Mock The Week’ (BBC Two). He has performed six solo shows at the Edinburgh Fringe to sell-out audiences and critical acclaim, with his 2019 show ‘Snitch’ being one of the best reviewed comedy shows at the Edinburgh Fringe. Agents Carly Peters Assistant [email protected] Holly Haycock 0203 214 0985 [email protected] Roles Television Production Character Director Company GUESSABLE Series 2 Guest Liz Clare & Ollie Tuesday's Child / Bartlett Comedy Central MOCK THE WEEK (S15 - 20) Panellist Angst Productions / BBC Two POINTLESS CELEBRITIES Guest Endemol Shine UK / BBC Series 14 CELEBRITY MASTERMIND Contestant Hat Trick Productions / BBC One RICHARD OSMAN'S HOUSE Guest Endemol Shine UK / BBC OF GAMES Series 4 Two United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Character Director Company COMEDY GAME NIGHT Guest Barbara Wiltshire Monkey Kingdom / Comedy Central / Channel 5 A LEAGUE OF THEIR OWN Panellist Sky One COMEDIANS: HOME ALONE Himself Done + Dusted / BBC Two LIVE AT THE APOLLO Stand-up Paul Wheeler Open Mike Productions Ltd / BBC Two COMEDY CENTRAL AT THE Stand-up Performer Comedy Central COMEDY STORE (2 Episodes) ROAST -

The Final BBC Young Jazz Musician 2020

The Final BBC young jazz musician 2020 The Final The Band – Nikki Yeoh’s Infinitum Nikki Yeoh (piano), Michael Mondesir (bass) and Mark Mondesir (drums) Matt Carmichael Matt Carmichael: Hopeful Morning Saxophone Matt Carmichael: On the Gloaming Shore Matt Carmichael: Sognsvann Deschanel Gordon Kenny Garrett arr. Deschanel Gordon: Haynes Here Piano Deschanel Gordon: Awaiting Thelonious Monk: Round Midnight Alex Clarke Bernice Petkere: Lullaby of the Leaves Saxophone Dave Brubeck: In Your Own Sweet Way Alex Clarke: Before You Arrived INTERVAL Kielan Sheard Kielan Sheard: Worlds Collide Bass Kielan Sheard: Wilfred's Abode Oscar Pettiford: Blues in the Closet Ralph Porrett Billy Strayhorn arr. Ralph Porrett: Lotus Blossom Guitar John Coltrane arr. Ralph Porrett: Giant Steps John Parricelli: Scrim Boudleaux Bryant: Love Hurts JUDGING INTERVAL Xhosa Cole BBC Young Jazz Musician 2018 Saxophone Thelonious Monk: Played Twice Xhosa Cole: George F on my mind Announcement and presentation of BBC Young Jazz Musician 2020 2 BBC young jazz musician 2020 Television YolanDa Brown Double MOBO award winning YolanDa Brown is the premier female saxophonist in the UK, known for delicious fusion of reggae, jazz and soul. Her debut album, “April Showers May Flowers” was no.1 on the jazz charts, her sophomore album released in 2017 “Love Politics War” also went to no.1 in the UK jazz charts. YolanDa has toured with The Temptations, Jools Holland’s Rhythm and Blues Orchestra, Billy Ocean and collaborated with artists such as Snarky Puppy’s Bill Laurance, Kelly Jones from Stereophonics and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. A broadcaster too – working across TV and radio, including her eponymous series for CBeebies, "YolanDa’s Band Jam", which recently won the Royal Television Society Awards as Best Children’s Programme. -

2012 Guide 56Pp+Cover

cc THE UK’S PREMIER MEETING PLACE FOR THE CHILDREN’S 4,5 &6 JULY 2012SHEFFIELD UK CONTENT INDUSTRIES CONFER- ENCE GUIDE 4_ 5_ & 6 JULY 2012 GUIDE SPONSOR Welcome Welcome to CMC and to Sheffield in the We are delighted to welcome you year of the Olympics both sporting and to Sheffield again for the ninth annual cultural. conference on children’s content. ‘By the industry, for the industry’ is our motto, Our theme this year is getting ‘ahead of which is amply demonstrated by the the game’ something which is essential number of people who join together in our ever faster moving industry. to make the conference happen. As always kids’ content makers are First of all we must thank each and every leading the way in utilising new one of our sponsors; we depend upon technology and seizing opportunities. them, year on year, to help us create an Things are moving so fast that we need, event which continues to benefit the kids’ more than ever, to share knowledge and content community. Without their support experiences – which is what CMC is all the conference would not exist. about – and all of this will be delivered in a record number of very wide-ranging Working with Anna, our Chair, and our sessions. Advisory Committee is a volunteer army of nearly 40 session producers. We are CMC aims to cover all aspects of the sure that over the next few days you will children's media world and this is appreciate as much as we do the work reflected in our broad range of speakers they put into creating the content from Lane Merrifield, the Founder of Club sessions to stretch your imagination Penguin and Patrick Ness winner of the and enhance your understanding. -

Onthefrontline

★ Paul Flynn ★ Seán Moncrieff ★ Roe McDermott ★ 7-day TV &Radio Saturday, April 25, 2020 MES TI SH IRI MATHE GAZINE On the front line Aday inside St Vincent’s Hospital Ticket INSIDE nthe last few weeks, the peopleof rear-viewmirror, there was nothing samey Ireland could feasibly be brokeninto or oppressivelyboring or pedestrian about Inside two factions:the haves and the suburban Dublinatall. Come to think of it, have-nots.Nope, nothing to do with the whys and wherefores of the estate I Ichildren, or holiday homes, or even grew up on were absolutely bewitching.As employment.Instead, I’m talking gardens. kids, we’d duck in and out of each other’s How I’ve enviedmysocialmediafriends houses: ahuge,boisterous,fluid tribe. with their lush, landscaped gardens, or Friends would stay for dinner if there were COLUMNISTS their functionalpatio furniture, or even enough Findus Crispy Pancakes to go 4 SeánMoncrieff their small paddling pools.AnInstagram round.Sometimes –and Idon’tknow how 6 Ross photo of someone enjoying sundownersin or why we ever did this –myfriends and I O’Carroll-Kelly their own back gardenisenough to tip me would swap bedrooms for the night,sothat 17 RoeMcDermott over the edge. Honestly, Icould never have they would be sleeping in my house and Iin 20 LauraKennedy foreseen ascenario in whichI’d look at theirs. Perhaps we fancied ourselvesas someone’smodest back garden and feel characters in our own high-concept, COVERSTORY genuine envy (and, as an interesting body-swap story.Yet no one’s parents 8 chaser, guilt for worrying aboutgardens seemed to mind. -

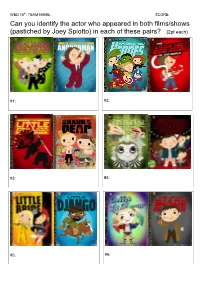

Can You Identify the Actor Who Appeared in Both Films/Shows (Pastiched by Joey Spiotto) in Each of These Pairs? (2Pt Each)

WED 15th: TEAM NAME: SCORE: Can you identify the actor who appeared in both films/shows (pastiched by Joey Spiotto) in each of these pairs? (2pt each) #1: #2: #3: #4: #5: #6: WED 15th: TEAM NAME: SCORE: #7: #8: #9: #10: #11: #12: #13: #14: WED 8th TEAM NAME: SCORE: Can you identify the movies whose posters inspired these 2017-8 Fringe photo shoots? (2pt each) #1. (5.6.4) #2. (7:7.2.3.6) #3. (3.8.6) #4. (3.4,3.3.3.3.4) #5. (10) #6. (4) #7 (4,5,4) #8. (7,2,3,5) #9. (7,4) #10: Whose face has Amy Annette replaced with her own for Q7? ACMS QUIZ – Aug-15 2018 Round # /20 pts Round # /20 pts 1. 1. 2. 2. 3. 3. 4. 4. 5. 5. 6. 6. 7. 7. 8. 8. 9. 9. 10. 10. Round # /20 pts Round # /20 pts 1. 1. 2. 2. 3. 3. 4. 4. 5. 5. 6. 6. 7. 7. 8. 8. 9. 9. 10. 10. ACMS QUIZ – Aug-15 2018 QUESTIONS: WED 15th AUGUST 2018 1) GENERAL KNOWLEDGE (A clue: YOU GOT AN OLOGY.) 1. M.Khan is what? 2. Who broke their hand in March, forcing a sold-out UK tour to be postponed? 3. Jonny Donahoe (new dad!) and Paddy Gervers are in what band together? 4. What is the name of the general manager of the Slough branch of Wernham-Hogg paper merchants? 5. Who plays Captain Martin Crieff in Cabin Pressure? 6. By what name are Ciaran Dowd, James McNicholas and Owen Roberts better known? 7. -

Programme 2018

PROGRAMME 2018 TUESDAY 25 SEPTEMBER 2018 DOUBLETREE BY HILTON COVENTRY, The world authority PARADISE WAY, COVENTRY, CV2 2ST in powered access WWW.IPAF.ORG/ELEVATION Download The Event App by EventsAIR Use app code: elevation18 Supporting sponsors: Official IPAF magazine: @ipaf.org #IPAFelevation MEETINGS SPEAKERS MALCOLM BOWERS – Director, Lifterz Ltd 09:30 - 12:00 > IPAF UK Country Council Meeting (York Suite) Malcolm entered the Access Industry in September 1970 working for Access Equipment Ltd 09:30 - 12:00 > IPAF UK & Ireland MCWP Working Group Meeting (Coventry Suite) (Zip-UP Hire Division). Formed Access Rental Ltd with colleagues in 1978 and sold in 1991 to fully listed Roskel Group PLC, forming a 10 depot network, who then sold on to Nationwide 09:30 - 12:00 > IPAF Rental+ Workshop (Canterbury 1)* Access Platforms in 1992. 13:00 - 13:45 > IPAF UK Open Meeting (Minster Suite 1)* *(Open for IPAF members and non-members) RAY COOKE – Principle Inspector Construction Sector Safety Unit, HSE Ray is a principle inspector with HSE and is head of the construction sector safety team. He joined HSE in 1985 and has inspected many different industries including specialising in docks, shipbuilding and ship repair, woodworking, plastics, food, health services and fairgrounds. CONFERENCE PROGRAMME GILES COUNCELL – Director of Operations, IPAF Giles is directly responsible for the management, administration and implementation of The conference will be hosted by Tim Whiteman - CEO & Managing Director, IPAF IPAF’s training programmes. He is a certified IPAF instructor for mobile elevating work 13:30 - 14:00 > Coffee and registration platforms (MEWPs) and a British Standards Institute (BSI) accredited ISO 9001lead auditor. -

Máire Messenger Davies

A1 The Children’s Media Foundation The Children’s Media Foundation P.O. Box 56614 London W13 0XS [email protected] First published 2013 ©Lynn Whitaker for editorial material and selection © Individual authors and contributors for their contributions. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of The Children’s Media Foundation, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organisation. You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover. ISBN 978-0-9575518-0-0 Paperback ISBN 978-0-9575518-1-7 E-Book Book design by Craig Taylor Cover illustration by Nick Mackie Opposite page illustration by Matthias Hoegg for Beakus The publisher wishes to acknowledge financial grant from The Writers’ Guild of Great Britain. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 Editorial Lynn Whitaker 5 2 The Children’s Media Foundation Greg Childs 10 3 The Children’s Media Foundation: Year One Anna Home 14 INDUSTRY NEWS AND VIEWS 4 BBC Children’s Joe Godwin 19 5 Children’s Content on S4C Sioned Wyn Roberts 29 6 Turner Kids’ Entertainment Michael Carrington 35 7 Turner: A View from the Business End Peter Flamman 42 8 Kindle Entertainment Melanie Stokes 45 9 MA in Children’s Digital Media Production, University of Salford Beth Hewitt 52 10 Ukie: UK Interactive Entertainment Jo Twist 57 POLICY, REGULATION AND DEBATE 11 Representation and Rights: The Use of Children -

Jarred Christmas

Jarred Christmas COMEDIAN, WRITER, TV & RADIO PRESENTER, IMPROVISER AND ACTOR ‘BEST CHILDREN’S SHOW’ NOMINEE – LEICESTER COMEDY FESTIVAL 2017 ‘BEST COMPERE’ - CHORTLE AWARDS 2016 New Zealand Sensation Jarred Christmas is one of the most innovative and exciting stand-ups on the UK circuit. A sought-after headliner famed for his quick-witted spontaneity, masterful skills of improvisation and energetic storytelling; Jarred is a regular at the Edinburgh Festival, and at comedy clubs and International festivals around the globe. He is a regular team member at The Comedy Store’s weekly topical show The Cutting Edge and was recently named Best Compere at the 2016 Chortle Awards; scooping the title for the second time. A dynamic onstage persona combined with the ability to improvise with anything that’s thrown his way makes Jarred’s comedy sizzle with originality. Early in his career he supported both Ross Noble and Tommy Tiernan on UK tours. He has since written and performed in countless shows at the Edinburgh Festival and has toured the UK in his own right with his solo shows Jarred Christmas Stands Up and Let’s Go Mofo. He has just played to packed theatres across the UK hosting the All Star Stand Up Tour. The show featured a world-class line-up of comedians and Jarred was honoured to be invited to host the show for the second year running. Jarred returned to the Edinburgh Festival this year, with a brand new solo stand-up show Remarkably Average. Combining his superlative improv and stand-up comedy skills (not to mention vocal agility), Jarred has recently developed The Mighty Beatbox Gameshow and a child-friendly version The Mighty Kids Beatbox Gameshow which he hosts alongside acclaimed beatboxer The Hobbit.