Hamlet on the Israeli Stage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996 Stage by Stage The Development of the National Theatre from 1848 Designed by Michael Mayhew Compiled by Lyn Haill & Stephen Wood With thanks to Richard Mangan and The Mander & Mitchenson Theatre Collection, Monica Sollash and The Theatre Museum The majority of the photographs in the exhibition were commissioned by the National Theatre and are part of its archive The exhibition was funded by The Royal National Theatre Foundation Richard Eyre. Photograph by John Haynes. 1988 To mark the company’s 25th birthday in Peter Hall’s last year as Director of the National October, The Queen approves the title ‘Royal’ Theatre. He stages three late Shakespeare for the National Theatre, and attends an plays (The Tempest, The Winter’s Tale, and anniversary gala in the Olivier. Cymbeline) in the Cottesloe then in the Olivier, and leaves to start his own company in the The funds raised are to set up a National West End. Theatre Endowment Fund. Lord Rayne retires as Chairman of the Board and is succeeded ‘This building in solid concrete will be here by the Lady Soames, daughter of Winston for ever and ever, whatever successive Churchill. governments can do to muck it up. The place exists as a necessary part of the cultural scene Prince Charles, in a TV documentary on of this country.’ Peter Hall architecture, describes the National as ‘a way of building a nuclear power station in the September: Richard Eyre takes over as Director middle of London without anyone objecting’. of the National. 1989 Alan Bennett’s Single Spies, consisting of two A series of co-productions with regional short plays, contains the first representation on companies begins with Tony Harrison’s version the British stage of a living monarch, in a scene of Molière’s The Misanthrope, presented with in which Sir Anthony Blunt has a discussion Bristol Old Vic and directed by its artistic with ‘HMQ’. -

25Th Annual Meeting in Washington, D.C., 1997

26-29 MARCH 1997 THE SHAKESPEARE ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA Albin 0. Kuhn Library University of Maryland, Baltimore County 1000 Hilltop Circle Baltimore, Maryland 21250 PHONE: 410-455-6788 FAX: 410-455-1063 E-MAIL: [email protected] THE SHAKESPEARE AssOCIATION OF AMERICA Executive Director, LENA COWEN 0RLIN University of Maryland, Baltimore County PRESIDENT BARBARA MOWAT Folger Shakespeare Library VICE PRESIDENT MARY BETH RosE Newberry Library TRUSTEES DAVID BEVINGTON University of Chicago A. R. BRAUNMULLER University of California, Los Angeles WILLIAM C. CARROLL Boston University MARGARET FERGUSON Columbia University COPPELIA KAHN Brown University ARTHUR F. KINNEY University of Massachusetts, Amherst PAUL WERSTINE King's College, University of Western Ontario PROGRAM COMMITTEE A. R. BRAUNMULLER, Chair University of California, Los Angeles )OHN ASTINGTON University of Toronto NAOMI). MILLER University of Arizona KAREN NEWMAN Brown University LOCAL ARRANGEMENTS COMMITTEE GAIL KERN PASTER George Washington University 5:30-8:00 p.m. BRUCE R. SMITH CONFERENCE ADMINISTRATION Workshop I: Teaching Shakespeare Georgetown University STATE RooM TERRY AYLSWORTH Leader: )ANET FIELD-PICKERING, Folger Shakespeare Library GEORGIANNA ZIEGLER University of Maryland, Baltimore County Folger Shakespeare Library WiTH THE ASSISTANCE OF SPONSORS rThursday, z 7 7vtard't; AMERICAN UNIVERSITY PATTY HOKE CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS )ACKIE HOPKINS THE UNIVERSITY OF DELAWARE )ULIE MORRIS 11:30 a.m.-5:00p.m. THE FOLGER SHAKESPEARE LiBRARY GEORGE WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY Registration GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY HAMPDEN-SYDNEY COLLEGE THE PROMENADE SPECIAL THANKS TO HOWARD UNIVERSITY )AMES MADISON UNIVERSITY Exhibits THE )OHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY ANDREA l. FRANK CABINET AND SENATE RooMs LOYOLA COLLEGE IN MARYLAND Sales Manager, The Mayflower Hotel THE UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND, BALTIMORE COUNTY IAN PEYMANI THE UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND, Catering and Convention Services Manager, The 12:00 noon-2:45p.m. -

'The Left's Views on Israel: from the Establishment of the Jewish State To

‘The Left’s Views on Israel: From the establishment of the Jewish state to the intifada’ Thesis submitted by June Edmunds for PhD examination at the London School of Economics and Political Science 1 UMI Number: U615796 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615796 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 F 7377 POLITI 58^S8i ABSTRACT The British left has confronted a dilemma in forming its attitude towards Israel in the postwar period. The establishment of the Jewish state seemed to force people on the left to choose between competing nationalisms - Israeli, Arab and later, Palestinian. Over time, a number of key developments sharpened the dilemma. My central focus is the evolution of thinking about Israel and the Middle East in the British Labour Party. I examine four critical periods: the creation of Israel in 1948; the Suez war in 1956; the Arab-Israeli war of 1967 and the 1980s, covering mainly the Israeli invasion of Lebanon but also the intifada. In each case, entrenched attitudes were called into question and longer-term shifts were triggered in the aftermath. -

Ian Wooldridge Director

Ian Wooldridge Director For details of Ian's freelance productions, and his international work in training and education go to www.ianwooldridge.com Agents Nicki Stoddart [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0869 Credits Theatre Production Company Notes ARTISTIC DIRECTOR, ROYAL LYCEUM THEATRE COMPANY, EDINBURGH, 1984-1993 THE TAMING OF THE SHREW Royal Lyceum Theatre Shakespeare Company, Edinburgh MERLIN Royal Lyceum Theatre Tankred Dorst Company Edinburgh ROMEO AND JULIET Royal Lyceum Theatre Shakespeare Company Edinburgh THE CRUCIBLE Royal Lyceum Theatre Arthur Miller Company Edinburgh THE ODD COUPLE Royal Lyceum Theatre Neil Simon Company Edinburgh JUNO AND THE PAYCOCK Royal Lyceum Theatre Sean O'Casey Company Edinburgh OTHELLO Royal Lyceum Theatre Shakespeare Company Edinburgh United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes THE HOUSE OF BERNARDA ALBA Royal Lyceum Theatre Federico Garcia Lorca Company Edinburgh HOBSON'S CHOICE Royal Lyceum Theatre Harold Brighouse Company Edinburgh DEATH OF A SALESMAN Royal Lyceum Theatre Arthur Miller Company Edinburgh THE GLASS MENAGERIE Royal Lyceum Theatre Tennessee Williams Company, Edinburgh ALICE IN WONDERLAND Royal Lyceum Theatre Adapted from the novel by Lewis Company, Edinburgh Carroll A MIDSUMMER NIGHT'S DREAM Royal Lyceum Theatre Shakespeare Company Edinburgh A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE Royal Lyceum Theatre Tennessee Williams Company, Edinburgh THE NUTCRACKER SUITE Royal Lyceum -

International Research Workshop of the Israel Science Foundation Rethinking Political Theatre in Western Culture

The Yolanda and David Katz Faculty of the Arts Department of Theatre Arts International Research Workshop of The Israel Science Foundation Rethinking Political Theatre in Western Culture March 2-4, 2015 | Tel Aviv University, Fastlicht Auditorium, Mexico Building | First Dayֿ | Second Dayֿ | Third Dayֿ Monday March 2, 2015 Tuesday March 3, 2015 Wednesday March 4, 2015 09:00 - 09:30 | Registration 09:00 - 10:00 | Keynote Lecture 09:00 - 10:00 | Keynote Lecture Chair: Shulamith Lev-Aladgem Chair: Madelaine Schechter 09:30 - 10:00 | Greetings Carol Martin, New-York University Imanuel Schipper, Zurich University of the Arts Zvika Serper, Dean of the Yolanda and David Katz Faculty of the Arts, On Location: Notes Towards a New Theory of Political Theatre Tel Aviv University Staging Public Space – Producing Neighbourship Respondent: Sharon Aronson-Lehavi Shulamith Lev-Aladgem, Chair of the Department of Theatre Arts, Respondent: Ati Citron Tel Aviv University 10:00 - 10:15 | Coffee Break 10:00 - 10:15 | Coffee Break 10:00 - 11:00 | Keynote Lecture Shulamith Lev-Aladgem and Gad Kaynar (Kissinger) 10:15 - 12:15 | Practical Workshop 10:15 - 11:45 | Workshop Session: Performance and Peacebuilding in Israel Rethinking Political Theatre: Introductory Notes Peter Harris, Tel Aviv University The Tami Steinmetz Center for Peace Research Playing with “Others” in a “Neutral Zone” 11:00 - 11:15 | Coffee Break Chair: Lee Perlman The Politics of Identity, Representation and Power - Relations 11:15 - 13:15 | Workshop Session 12:15 - 12:30 | Coffee Break Aida -

AURDIP Association of Academics for the Respect of International Law in Palestine

AURDIP Association of Academics for the Respect of International Law in Palestine Benjamin Netanyahu, Prime Minister of Israel 3 Kaplan St. Hakirya Jerusalem 91950, Israel [email protected] Dear Prime Minister Netanyahu: We are writing to urge you to order the immediate release of Dr. Imad Ahmad Barghouthi from Israeli military custody. Dr. Barghouthi, a Palestinian resident of the West Bank, is an astrophysicist and professor of physics at Al-Quds University in Jerusalem. He was reportedly arrested by Israeli soldiers at the military checkpoint at Nabi Saleh in the West Bank, northwest of Ramallah on 24 April 2016. The Times of Israel reported that "neither the IDF nor Israel Police would comment on the matter, and it remains unclear which branch of the Israeli security forces was responsible for his arrest." The Palestine Information Center reported that on 2 May 2016, "An Israeli court ... issued an administrative detention order against Professor Barghouthi”i. Professor Barghouthi is being held without chargeii, a serious violation of human rights. As described in the journal Nature, Professor Barghouthi was previously arrested without charge by Israeli Border Police on 6 December 2014 when he attempted to cross the border from the West Bank to Jordan to board a flight to the United Arab Emirates so that he could attend a meeting of the Arab Union of Astronomy and Space Sciences, an organization he helped to found.iii Professor Barghouthi's attorney at that time, Jawad Boulos, alleged that Dr. Barghouthi was arrested because of his statements in support of Palestinian activities during Israel’s invasion of the Gaza Strip the previous summer, and that during interrogations Dr. -

Women, Theater, and the Holocaust FOURTH RESOURCE HANDBOOK / EDITION a Project Of

Women, Theater, and the Holocaust FOURTH RESOURCE HANDBOOK / EDITION A project of edited by Rochelle G. Saidel and Karen Shulman Remember the Women Institute, a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit corporation founded in 1997 and based in New York City, conducts and encourages research and cultural activities that contribute to including women in history. Dr. Rochelle G. Saidel is the founder and executive director. Special emphasis is on women in the context of the Holocaust and its aftermath. Through research and related activities, including this project, the stories of women—from the point of view of women—are made available to be integrated into history and collective memory. This handbook is intended to provide readers with resources for using theatre to memorialize the experiences of women during the Holocaust. Women, Theater, and the Holocaust FOURTH RESOURCE HANDBOOK / EDITION A Project of Remember the Women Institute By Rochelle G. Saidel and Karen Shulman This resource handbook is dedicated to the women whose Holocaust-related stories are known and unknown, told and untold—to those who perished and those who survived. This edition is dedicated to the memory of Nava Semel. ©2019 Remember the Women Institute First digital edition: April 2015 Second digital edition: May 2016 Third digital edition: April 2017 Fourth digital edition: May 2019 Remember the Women Institute 11 Riverside Drive Suite 3RE New York,NY 10023 rememberwomen.org Cover design: Bonnie Greenfield Table of Contents Introduction to the Fourth Edition ............................................................................... 4 By Dr. Rochelle G. Saidel, Founder and Director, Remember the Women Institute 1. Annotated Bibliographies ....................................................................................... 15 1.1. -

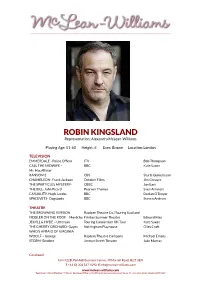

Mwm Cv Robinkingsland 2

ROBIN KINGSLAND Representation: Alexandra McLean-Williams Playing Age: 51-60 Height: 6’ Eyes: Brown Location: London TELEVISION EMMERDALE - Police Officer ITV Bob Thompson CALL THE MIDWIFE – BBC Kate Saxon Mr. MacAllister RANSOM 3 CBS Sturla Gunnarsson CHAMELEON- Frank Jackson October Films Jim Greayer THE SPARTICLES MYSTERY- CBBC Jon East THE BILL- John Picard Pearson Thames Sven Arnstein CASUALITY-Hugh Jacobs BBC Declan O’Dwyer SPACEVETS- Dogsbody BBC Steven Andrew THEATRE THE BROWNING VERSION Rapture Theatre Co,/Touring Scotland FIDDLER ON THE ROOF – Mordcha Frinton Summer Theatre Edward Max JEKYLL & HYDE – Utterson Touring Consortium UK Tour Kate Saxon THE CHERRY ORCHARD- Gayev Nottingham Playhouse Giles Croft WHO’S AFRAID OF VIRGINIA WOOLF – George Rapture Theatre Company Michael Emans STORM- Brother Jermyn Street Theatre Jake Murray Continued Unit F22B, Parkhall Business Centre, 40 Martell Road, SE21 8EN T +44 (0) 203 567 1090 E [email protected] www.mclean-williams.com Registered in England Number: 7432186 Registered Office: C/O William Sturgess & Co, Burwood House, 14 - 16 Caxton Street, London SW1H 0QY ROBIN KINGSLAND continued PRIVATE LIVES – Victor Mercury Theatre Colchester Esther Richardson ROMEO & JULIET – Montague Crucible Theatre Sheffield Jonathan Humphreys ARCADIA – Captain Bruce Nottingham Playhouse Giles Croft HAMLET- Claudius Secret Theatre, Edinburgh Fringe Richard Crawford Festival THE OTHER PLACE – Ian Smithson RADA Geoffrey Williams WITNESS FOR THE PROSECUTION Vienna English Theatre, Philip Dart Sir Wilfrid -

Itineraries of Jewish Actors During the Firs

ABSTRACT Reconstructing a Nomadic Network: Itineraries of Jewish Actors during the First Lithuanian Independence !is article discusses the phenomenon of openness and its nomadic nature in the activities of Jewish actors performing in Kaunas during the "rst Lithuanian independence. Jewish theatre between the two world wars had an active and intense life in Kaunas. Two to four independent theatres existed at one time and international stars were often touring in Lithuania. Nevertheless, Lithuanian Jewish theatre life was never regarded by Lithuanian or European theatre society as signi"cant since Jewish theatre never had su#cient ambition and resources to become such. On the one hand, Jewish theatre organized itself in a nomadic way, that is, Jewish actors and directors were constantly on the road, touring from one country to another. On the other hand, there was a tense competition between the local Jewish theatres both for subsidies and for audiences. !is competition did not allow the Jewish community to create a theatre that could represent Jewish culture convincingly. Being a theatre of an ethnic minority, Jewish theatre did not enjoy the same attention from the state that was given to the Lithuanian National !eatre. !e nomadic nature of the Jewish theatre is shown through the perspective of the concept of nomadic as developed by Deleuze and Guattari. Keywords: Jewish theatre, Kaunas, nomadic, "rst Lithuanian independence, Yiddish culture. BIOGRAPHY management. 78 Nordic Theatre Studies vol. 27: no. 1 Nordic Theatre Studies vol. 27: no. 1 Reconstructing a Nomadic Network Itineraries of Jewish Actors during the First Lithuanian Independence INA PUKELYTĖ Networking and the maintenance of horizontal links of intermezzo1 and thus implicitly shows the inter- were always common to European theatre commu- relation between theatre and the nomadic: “!e nities. -

38Th Annual Meeting in Chicago, Illinois, 2010

SHAKESPEARE ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA Program of the 38th annual meeting 1-3 aPril 2010 the hyatt regency chicago 1 The 38th President Annual PauL yaChnin McGill University Meeting of the Vice-President Shakespeare russ MCDonaLD Association of Goldsmiths College, University of London America Immediate Past President CoPPéLia Kahn Executive Director Brown University Lena Cowen orLin Georgetown University Trustees Memberships Manager reBeCCa BushneLL Donna even-Kesef University of Pennsylvania Georgetown University Kent Cartwright University of Maryland Publications Manager BaiLey yeager heather JaMes Georgetown University University of Southern California Lynne Magnusson University of Toronto eriC rasMussen University of Nevada vaLerie wayne University of Hawai’i 1 Program Planning Committee Sponsors of the 38th reBeCCa BushneLL, Chair Annual Meeting University of Pennsylvania LinDa Charnes Loyola University Chicago Indiana University University of Notre Dame anDrew JaMes hartLey University of North Carolina, Charlotte University of Chicago JaMes Kearney University of California, Santa Barbara University of Illinois, Urbana- Champaign Local Arrangements suzanne gossett University of Michigan Loyola University Chicago Northwestern University With the assistance of: DaviD Bevington Wayne State University University of Chicago Northeastern Illinois University John D. Cox Hope College University of Wisconsin BraDLey greenBurg Northeastern Illinois University Hope College Peter hoLLanD University of Notre Dame and Kenneth s. JaCKson Wayne State University Georgetown University CaroL thoMas neeLy University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign Curtis Perry University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign riCharD strier University of Chicago vaLerie trauB University of Michigan wenDy waLL Northwestern University MiChaeL witMore University of Wisconsin 1 2010 Program Guide Thursday, 1 April 10:00 a.m. Registration in Regency Foyer 6 Book Exhibits in Regency Foyer 6 Buses Depart for Backstage Tour of the Chicago Shakespeare Theater 6 1:30 p.m. -

Israel Prize

Year Winner Discipline 1953 Gedaliah Alon Jewish studies 1953 Haim Hazaz literature 1953 Ya'akov Cohen literature 1953 Dina Feitelson-Schur education 1953 Mark Dvorzhetski social science 1953 Lipman Heilprin medical science 1953 Zeev Ben-Zvi sculpture 1953 Shimshon Amitsur exact sciences 1953 Jacob Levitzki exact sciences 1954 Moshe Zvi Segal Jewish studies 1954 Schmuel Hugo Bergmann humanities 1954 David Shimoni literature 1954 Shmuel Yosef Agnon literature 1954 Arthur Biram education 1954 Gad Tedeschi jurisprudence 1954 Franz Ollendorff exact sciences 1954 Michael Zohary life sciences 1954 Shimon Fritz Bodenheimer agriculture 1955 Ödön Pártos music 1955 Ephraim Urbach Jewish studies 1955 Isaac Heinemann Jewish studies 1955 Zalman Shneur literature 1955 Yitzhak Lamdan literature 1955 Michael Fekete exact sciences 1955 Israel Reichart life sciences 1955 Yaakov Ben-Tor life sciences 1955 Akiva Vroman life sciences 1955 Benjamin Shapira medical science 1955 Sara Hestrin-Lerner medical science 1955 Netanel Hochberg agriculture 1956 Zahara Schatz painting and sculpture 1956 Naftali Herz Tur-Sinai Jewish studies 1956 Yigael Yadin Jewish studies 1956 Yehezkel Abramsky Rabbinical literature 1956 Gershon Shufman literature 1956 Miriam Yalan-Shteklis children's literature 1956 Nechama Leibowitz education 1956 Yaakov Talmon social sciences 1956 Avraham HaLevi Frankel exact sciences 1956 Manfred Aschner life sciences 1956 Haim Ernst Wertheimer medicine 1957 Hanna Rovina theatre 1957 Haim Shirman Jewish studies 1957 Yohanan Levi humanities 1957 Yaakov -

Here Has Been a Substantial Re-Engagement with Ibsen Due to Social Progress in China

2019 IFTR CONFERENCE SCHEDULE DAY 1 MONDAY JULY 8 WG 1 DAY 1 MONDAY July 8 9:00-10:30 WG1 SAMUEL BECKETT WORKING GROUP ROOM 204 Chair: Trish McTighe, University of Birmingham 9:00-10:00 General discussion 10:00-11:00 Yoshiko Takebe, Shujitsu University Translating Beckett in Japanese Urbanism and Landscape This paper aims to analyze how Beckett’s drama especially Happy Days is translated within the context of Japanese urbanism and landscape. According to Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Studies, “shifts are seen as required, indispensable changes at specific semiotic levels, with regard to specific aspects of the source text” (Baker 270) and “changes at a certain semiotic level with respect to a certain aspect of the source text benefit the invariance at other levels and with respect to other aspects” (ibid.). This paper challenges to disclose the concept of urbanism and ruralism that lies in Beckett‘s original text through the lens of site-specific art demonstrated in contemporary Japan. Translating Samuel Beckett’s drama in a different environment and landscape hinges on the effectiveness of the relationship between the movable and the unmovable. The shift from Act I into Act II in Beckett’s Happy Days gives shape to the heroine’s urbanism and ruralism. In other words, Winnie, who is accustomed to being surrounded by urban materialism in Act I, is embedded up to her neck and overpowered by the rural area in Act II. This symbolical shift experienced by Winnie in the play is aesthetically translated both at an urban theatre and at a cave-like theatre in Japan.