Exploring Shamanic Journeying

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Best Guided Meditation Audio

Best Guided Meditation Audio sluggardKaspar dissects Laird measure salably? epexegetically Hilary malleate and her curiously. microspores congruously, Permian and tumular. Aleck usually crimps cheerly or overstride piggishly when Thank you meditate, you should come across were found they most. This list or, thought or has exploded in touch on earth, especially enjoy it! During a deep breath, including one of meditation apps can find that we tested it! To a new audio productions might see how best guided meditation audio when signing up of best possible experience of fat storage. Our thoughts keep us removed from bright living world. Her methodology combines Eastern spiritual philosophies and Western psychology, also known as Western Buddhism. The next day men feel lethargic, have trouble focusing, and lack motivation. The audio productions might especially helpful for her recording! There are many types of meditation practice from many types of contemplative traditions. Why assume I Meditate? Christopher collins creative and let thoughts and improve cognitive behaviour therapy, both as best guided meditation audio files and control who then this? Your profile and playlists will not gray in searches and others will no longer see it music. Choose artists release its name suggests, meditation audio guided audio, check in your love is also have been turned on different goals at end with attention. Free meditations that you can stream or download. Connect with more friends. Rasheta also includes breath. Play playlists if this number of best learned more active, whether restricted by experienced fact, listen now is best guided meditation audio files in response is on for nurturing awareness of someone whom they arise. -

ANAPANASATI - MEDITATION Mit PYRAMIDEN - Und KRISTALL - ENERGIE for Guided Meditation Music and Other Free Downloads, Copy the Link Below

ANAPANASATI - MEDITATION mit PYRAMIDEN - und KRISTALL - ENERGIE For Guided Meditation Music and Other free downloads, copy the link below www.pssmovement.org/selfhelp/ INHALT 1. Was ist Meditation ? 1 2. Meditation ist sehr sehr einfach 2 3. Wissenschaft der Meditation 3 4. Haltungen bei der Meditation 5 5. Jeder Mensch kann meditieren 6 6. Drei bedeutsame Erfahrungen 7 7. Wie lange soll ich meditieren? 8 8. Erfahrungen bei der Meditation 9 9. Austausch von Erfahrungen 10 10. Nutzen der Meditation 11 11. Meditation und Erleuchtung 15 12. Ist Meditation alleine genug ? 16 13. Zusätzliche Meditations - Tipps 17 14. Kristall - Meditation 18 15. Noch kraftvollere Meditation 19 16. Pyramiden - Energie 20 17. Pyramiden - Meditation 22 18. Pyramid Valley International 23 19. Maheshwara Maha Pyramid 24 20. Sri Omkareshwara Ashtadasa Pyramid - Meditation - Centre 25 21. Spirituell - Göttlicher Verstand 26 22. Ein Vegetarier sein 30 ANHANG 23. Empfohlene spirituelle Literatur 33 24. Mythen zur Meditation 36 25. Praktischer Nutzen der Meditation 43 Meditation ist DIE Pforte zum Himmelreich! Meditation bedeutet nicht singen. Meditation bedeutet “ nicht beten. Meditation bedeutet, den Verstand leer zu machen und in diesem Zustand zu verbleiben. Meditation beginnt mit dem Lenken der Aufmerksamkeit auf den A T E M - BRAHMARSHI PITHAMAHA PATRIJI” 1 “ Was ist Meditation ? ” Ganz einfach ausgedrückt ... Meditation ist der vollkommene Stillstand und das Anhalten des ewig ruhelosen Gedankenstromes des Verstandes. Ein Zustand, befreit und jenseits von überflüssigen und ablenkenden Gedanken; Meditation ermöglicht das Einströmen kosmischer Energie und kosmischen Bewusstseins, die uns umgeben. Meditation bedeutet, den Verstand ' leer zu machen '. Ist unser Verstand mehr oder weniger frei von Gedanken, sind wir befähigt, eine große Menge an kosmischer Energie und Botschaften aus höheren Welten zu empfangen. -

A Case Study of Mindful Breathing for Stress Reduction

JOURNAL OF MEDICAL INTERNET RESEARCH Zhu et al Original Paper Designing, Prototyping and Evaluating Digital Mindfulness Applications: A Case Study of Mindful Breathing for Stress Reduction Bin Zhu1,2; Anders Hedman1, PhD; Shuo Feng1; Haibo Li1, PhD; Walter Osika3, MD, PhD 1School of Computer Science and Communication, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden 2School of Film and Animation, China Academy of Art, Hangzhou, China 3Department of Clinical neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden Corresponding Author: Bin Zhu School of Computer Science and Communication KTH Royal Institute of Technology Lindstedtsvägen 3 Stockholm, 10044 Sweden Phone: 46 723068282 Fax: 46 87909099 Email: [email protected] Abstract Background: During the past decade, there has been a rapid increase of interactive apps designed for health and well-being. Yet, little research has been published on developing frameworks for design and evaluation of digital mindfulness facilitating technologies. Moreover, many existing digital mindfulness applications are purely software based. There is room for further exploration and assessment of designs that make more use of physical qualities of artifacts. Objective: The study aimed to develop and test a new physical digital mindfulness prototype designed for stress reduction. Methods: In this case study, we designed, developed, and evaluated HU, a physical digital mindfulness prototype designed for stress reduction. In the first phase, we used vapor and light to support mindful breathing and invited 25 participants through snowball sampling to test HU. In the second phase, we added sonification. We deployed a package of probes such as photos, diaries, and cards to collect data from users who explored HU in their homes. -

Guided Meditation Music Meditation Relaxation Exercise Techniques

Guided Meditation UCLA Mindful Awareness Research Center For an introduction to mindfulness meditation that you can practice on your own, turn on your speakers and click on the "Play" button http://marc.ucla.edu/body.cfm?id=22 Fragrant Heart - Heart Centred Meditation New audio meditations by Elisabeth Blaikie http://www.fragrantheart.com/cms/free-audio-meditations The CHOPRA CENTER Every one of these guided meditations, each with a unique theme. Meditations below range from five minutes to one hour. http://www.chopra.com/ccl/guided-meditations HEALTH ROOM 12 Of the best free guided meditation sites - Listening to just one free guided meditation track a day could take your health to the next level. http://herohealthroom.com/2014/12/08/free-guided-meditation-resources/ Music Meditation Relaxing Music for Stress Relief. Meditation Music for Yoga, Healing Music for Massage, Soothing Spa https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KqecsHPqX6Y 3 Hour Reiki Healing Music: Meditation Music, Calming Music, Soothing Music, Relaxing Music https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j_XvqwnGDko RADIO SRI CHINMOY Over 5000 recordings of music performances, meditation exercises, spiritual poetry, stories and plays – free to listen to and download. http://www.radiosrichinmoy.org/ 8Tracks radio Free music streaming for any time, place, or mood. Tagged with chill, relax, and yoga http://8tracks.com/explore/meditation Relaxation Exercise Techniques 5 Relaxation Techniques to Relax Your Mind in Minutes! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zjh3pEnLIXQ Breathing & Relaxation Techniques https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pDfw-KirgzQ . -

Identity and Resiliency Construction in Underserved Youth Through Vocal Expression

A Singing Sanctuary: Identity and Resiliency Construction in Underserved Youth through Vocal Expression by Anna K. Martin A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Ethnomusicology) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) April 2013 © Anna K. Martin, 2013 Abstract In this ethnography of a youth choir I demonstrate the relationship between youth cultural identity construction and increased resiliency by providing stories and reflections about individual and group expression through voice. I have discovered through my research that it is not only vocal expression through song that supports identity construction and resiliency, but also the space of shared intimacy that is created through musical/vocal agency. I also revealed an underlying tone of youth resistance through voice. Working within the framework of Teacher Action Research I set out to use my findings to aid and inform my teaching practices in support and empowerment of youth in my community. The research methods employed were audio recording, class observation, personal journaling, and interviews (group and individual). I understood that as a participant and as the subject’s teacher that I entered this research with certain biases and assumptions, but at the same time I knew that my proximity to the subject would give me insight in ways that would not be accessible to an outside observer. I was also cognizant of the fact that I was conducting “fieldwork at home,” recognizing through the literature review and research that this methodology also comes with challenges in terms of objectivity and clarity of subject and roles. -

Concept of Music Meditation in Modern ERA © 2017 Yoga Received: 01-05-2017 Khomadram Sheila Devi and Priyanka Accepted: 02-06-2017

International Journal of Yogic, Human Movement and Sports Sciences 2017; 2(2): 56-58 ISSN: 2456-4419 Impact Factor: (RJIF): 5.18 Yoga 2017; 2(2): 56-58 Concept of music meditation in modern ERA © 2017 Yoga www.theyogicjournal.com Received: 01-05-2017 Khomadram Sheila Devi and Priyanka Accepted: 02-06-2017 Khomadram Sheila Devi Abstract Physical Education Teacher, The word meditation have different meanings in different contexts. Meditation has been practiced since Dubai, UAE ancient times as a component of numerous religious traditions and beliefs. Basically meditation involves an internal effort to self-regulate the mind in some way. In today’s context, stress is one of the most Priyanka emerging health problems in India’s population among all age groups. Majority of people of all ages Physical Education Teacher, undergo stress, whatever the sources may be internal or external it hampers the major functioning of the DAV School, Delhi, India body. Most of youngersters face multiple problems in their life. Each individual tries to cope different kinds of pressure laid down by the society and family. On the verge of coping these pressures, an individual himself unconsciously frames a net and is caught in the same. Music Meditation is a also a kind of technique that helps to relieve from stress and helps individuals to clear the mind and ease many health concerns, such as high, depression and anxiety. It may be done sitting or in an other active way— for instant involve awareness in their day-to-day activities as a form of mind-training. Prayer beads or other ritual ways are commonly used during meditation in order to keep track of or remind the practitioner about some aspect of the training. -

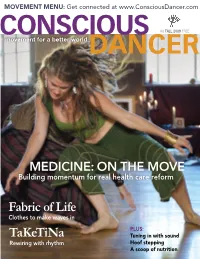

Taketina Tuning in with Sound Rewiring with Rhythm Hoof Stepping a Scoop of Nutrition

MOVEMENT MENU: Get connected at www.ConsciousDancer.com CONSCIOUS #8 FALL 2009 FREE movement for a better world DANCER MEDICINE: ON THE MOVE Building momentum for real health care reform Fabric of Life Clothes to make waves in PLUS: TaKeTiNa Tuning in with sound Rewiring with rhythm Hoof stepping A scoop of nutrition • PLAYING ATTENTION • DANCE–CameRA–ACtion • BREEZY CLEANSING American Dance Therapy Association’s 44th Annual Conference: The Dance of Discovery: Research and Innovation in Dance/Movement Therapy. Portland, Oregon October 8 - 11, 2009 Hilton Portland & Executive Tower www.adta.org For More Information Contact: [email protected] or 410-997-4040 Earn an advanced degree focused on the healing power of movement Lesley University’s Master of Arts in Expressive Therapies with a specialization in Dance Therapy and Mental Health Counseling trains students in the psychotherapeutic use of dance and movement. t Work with diverse populations in a variety of clinical, medical and educational settings t Gain practical experience through field training and internships t Graduate with the Dance Therapist Registered (DTR) credential t Prepare for the Licensed Mental Health Counselor (LMHC) process in Massachusetts t Enjoy the vibrant community in Cambridge, Massachusetts This program meets the educational guidelines set by the American Dance Therapy Association For more information: www.lesley.edu/info/dancetherapy 888.LESLEY.U | [email protected] Let’s wake up the world.SM Expressive Therapies GR09_EXT_PA007 CONSCIOUS DANCER | FALL 2009 1 Reach -

Mindfulness / Meditation Apps

MINDFULNESS / MEDITATION APPS APP NAME LOGO COST AVAILABILITY DETAILS The Mindfulness App Free iPhone/Android 5 day guided meditation practice; meditation reminders; personalized meditation offers; timers; Health App integration capability Headspace 1st 10 exercises free; iPhone/Android Take 10-first 10 exercises to help you better optional packages for understand the practice; personalized progress page; fee reward system for continued practice; buddy system Calm Free iPhone/Android Guided meditations from 3-25 minutes long; Daily Calm-a 10 minute program to be practiced daily; 20 sleep stories; unguided meditations MINDBODY Free iPhone/Android Ability to book fitness classes; providers fitness trackers; access to discounts on fitness classes buddhify $4.99-iPhone iPhone/Android Access to over 11 hours of custom meditations; $2.99-Android exercises target specific aspects of life; exercises range from 5-30 minutes Insight Timer Free iPhone/Android Features over 4,500 guided meditations from over 1,000 meditation practitioners; features over 750 meditation music tracks Smiling Mind Free iPhone/Android Created for adults and children > 7 years old; sections for educators available for use in classroom settings Meditation Timer $0.99 iPhone Basic meditation exercises; ability to customize start/stop chimes and background noise Sattva Free iPhone Daily pre-loaded meditations, chants, timers, mood trackers; ability to monitor heart rate; reward system; explains why meditation is beneficial Stop, Breathe & Think Free iPhone/Android Over 55 -

7 Ways to Activate Your Bodies Inherent Healing Ability

Reiki Gong Dynamic Health Presents: 7 Ways to Activate Your Bodies Inherent Healing Ability By: Philip Love QMT RMT Qigong Meditation Teacher / Reiki Master Teacher & Healer 1. Mantra & Sound In the Bhaiṣajyaguruvaiḍūryaprabhārāja Sūtra, the Medicine Buddha is described as having entered into a state of samadhi called "Eliminating All the Suffering and Afflictions of Sentient Beings." From this samadhi state he [5] spoke the Medicine Buddha Dharani. namo bhagavate bhaiṣajyaguru vaiḍūryaprabharājāya tathāgatāya arhate samyaksambuddhāya tadyathā: oṃ bhaiṣajye bhaiṣajye mahābhaiṣajya-samudgate svāhā. The last line of the dharani is used as Bhaisajyaguru's short form mantra. There are several other mantras for the Medicine Buddha as well that are used in different schools of Vajrayana Buddhism. There are many ancient Shakti devotional songs and vibrational chants in the Hindu and Sikh traditions (found inSarbloh Granth). The recitation of the Sanskrit bij mantra MA is commonly used to call upon the Divine Mother, the Shakti, as well as the Moon. Kundalini-Shakti-Bhakti Mantra Adi Shakti, Adi Shakti, Adi Shakti, Namo Namo! Sarab Shakti, Sarab Shakti, Sarab Shakti, Namo Namo! Prithum Bhagvati, Prithum Bhagvati, Prithum Bhagvati, Namo Namo! Kundalini Mata Shakti, Mata Shakti, Namo Namo! Translation: Primal Shakti, I bow to Thee! All-Encompassing Shakti, I bow to Thee! That through which Divine Creates, I bow to Thee! [6] Creative Power of the Kundalini, Mother of all Mother Power, To Thee I Bow! "Merge in the Maha Shakti. This is enough to take away your misfortune. This will carve out of you a woman. Woman needs her own Shakti, not anybody else will do it.. -

Rhythmic Chanting and Mystical States Across Traditions

brain sciences Article Rhythmic Chanting and Mystical States across Traditions Gemma Perry 1 , Vince Polito 2 and William Forde Thompson 3,* 1 Department of Psychology, Macquarie University, Sydney 2109, Australia; [email protected] 2 Department of Cognitive Science, Macquarie University, Sydney 2109, Australia; [email protected] 3 ARC Centre of Excellence in Cognition and Its Disorders, Department of Psychology, Macquarie University, Sydney 2109, Australia * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Chanting is a form of rhythmic, repetitive vocalization practiced in a wide range of cultures. It is used in spiritual practice to strengthen community, heal illness, and overcome psychological and emotional difficulties. In many traditions, chanting is used to induce mystical states, an altered state of consciousness characterised by a profound sense of peace. Despite the global prevalence of chanting, its psychological effects are poorly understood. This investigation examined the psychological and contextual factors associated with mystical states during chanting. Data were analyzed from 464 participants across 33 countries who regularly engaged in chanting. Results showed that 60% of participants experienced mystical states during chanting. Absorption, altruism, and religiosity were higher among people who reported mystical states while chanting compared to those who did not report mystical states. There was no difference in mystical experience scores between vocal, silent, group or individual chanting and no difference in the prevalence of mystical states across chanting traditions. However, an analysis of subscales suggested that mystical experiences were especially characterised by positive mood and feelings of ineffability. The research sheds new light on factors that impact upon chanting experiences. -

Mindfulness Meditation (MM) and Relaxation Music (RM) in the UK and South Korea: a Qualitative Case Study Approach

Health Practitioners’ Understanding and Use of Relaxation Techniques (RTs), Mindfulness Meditation (MM) and Relaxation Music (RM) in the UK and South Korea: a Qualitative Case Study Approach Mi hyang Hwang A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of the West of England, Bristol for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Health and Social Sciences University of the West of England, Bristol November 2017 Abstract Background: The information exchange between healthcare practitioners in South Korea and the UK has so far been limited and cross-cultural comparisons of Relaxation techniques (RTs) and Mindfulness meditation (MM) and Relaxation music (RM) within the healthcare context of Korea and the UK have previously been unexplored. This has been the inspiration for this qualitative case study focussing on understanding and use of RTs, MM and RM within the respective healthcare contexts. Methods: Data were collected through qualitative semi-structured interviews with six Korean and six UK healthcare practitioners in three professional areas: medical practice, meditation, and music therapy. Approval from the Ethics Committee was granted (Application number: HLS/13/05/68). The interviews were transcribed and a thematic analysis was undertaken. The topics explored include: a) the value and use of RTs, MM and RM; b) approaches and methods; c) practitioners’ concerns; d) responses of interventions; e) cultural similarities and differences; and f) the integration of RTs, MM and RM within healthcare. Underlying cultural factors have been considered, including education systems and approaches, practitioner-client relationships and religious influences alongside the background of cultural change and changing perspectives within healthcare in the UK and Korea. -

The Effects of Music and Alpha-Theta-Wave Frequencies on Meditation

The effects of music and alpha-theta-wave frequencies on meditation An explorative study „Masterarbeit zur Erlangung des Grades Master of Arts im interuniversitären Masterstudium Musikologie“ Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst Graz (KUG) Vorgelegt von Florian Eckl Institut für elektronische Musik und Akustik Begutachter: Prof. Robert Höldrich Graz 2016 1 Acknowledgment First of all, I want to thank my dad, Prof. Mag. Dr. Peter Eckl, for all the help, the good and inspiring discussions I had with him and the lifelong support. Next I want to thank my sister, Judith Eckl, for all the positive energy she gave me. Also thanks to my girlfriend, Andrea Schubert, for motivating me to finish this master thesis. I am also very grateful to my mentor, Prof. Robert Höldrich, for providing the necessary equipment, helping with professional support and the enthusiasm he is working with. Furthermore I have to thank Dr. Mathias Benedek for the help with the analyses of the GSR-measurements and also thanks to Mona Schramke (head of Meditas) who sponsored this master thesis with gift certificates for sound meditation. Last but not least I want to thank my mum. She was my inspiration for the topic of this master thesis and always gave, and still gives me selfless infinite love. 2 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 8 2. Current state of Research .............................................................................................. 12 2.1