Chapter 6 Lizards and Related Forms As

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Case for Some Nuaulu Reptiles In: Journal D'agriculture Traditionnelle Et De Botanique Appliquée

Roy F. Ellen Andrew F. Stimson James Menzies The content of categories and experience; the case for some Nuaulu reptiles In: Journal d'agriculture traditionnelle et de botanique appliquée. 24e année, bulletin n°1, Janvier-mars 1977. pp. 3- 22. Citer ce document / Cite this document : Ellen Roy F., Stimson Andrew F., Menzies James. The content of categories and experience; the case for some Nuaulu reptiles. In: Journal d'agriculture traditionnelle et de botanique appliquée. 24e année, bulletin n°1, Janvier-mars 1977. pp. 3-22. http://www.persee.fr/web/revues/home/prescript/article/jatba_0183-5173_1977_num_24_1_3260 ETUDES ET DOSSIERS THE THECONTENT CASE OFFOR CATEGORIES SOME NUAULU AND REPTILESEXPERIENCE; By Roy F. ELLEN *, Andrew F. STIMSON **, James MENZIES *** This is the second paper in a series of systematic descriptive accounts of Nuaulu ethnozoology. In the first (Ellen, Stimson and Menzies 1976) we presented data on Nuaulu categories for amphibians, as well as providing information on location, ecology and ethnography, and on basic techniques employed in field investigations. The present report encompasses the identification, utilization and general knowledge of reptiles (excluding snakes) of the Nuaulu people of south central Seram, eastern Indonesia (1). We note the main details of the non-serpentine reptile fauna of the region and discuss Nuaulu categories applied to turtles, crocodiles and lizards, their classificatory arrangement and social uses. Throughout, particular emphasis has been placed on cognitive and lexical variation between informants, something neglected in earlier studies. This is dealt with in some detail. * University of Kent at Canterbury (Grande-Bretagne). ** British Museum (Natural History), London (Grande-Bretagne) *** University of Papua New Guinea, Port Moresby (Nouvelle-Guinée). -

Conservation of Herpetofauna in Bantimurung Bulusaraung National Park, South Sulawesi, Indonesia

CONSERVATION OF HERPETOFAUNA IN BANTIMURUNG BULUSARAUNG NATIONAL PARK, SOUTH SULAWESI, INDONESIA Final Report 2008 By: M. Irfansyah Lubis, Wempy Endarwin, Septiantina D. Riendriasari, Suwardiansah, Adininggar U. Ul-Hasanah, Feri Irawan, Hadijah Aziz K., and Akmal Malawi Departemen Konservasi Sumberdaya Hutan Fakultas Kehutanan Institut Pertanian Bogor Bogor Indonesia 16000 Tel : +62 – 251 – 621 947 Fax: +62 – 251 – 621 947 Email: [email protected] (team leader) Conservation of Herpetofauna in Bantimurung Bulusaraung National Park, South Sulawesi, Indonesia Executive Summary Sulawesi is an island with complex geological and geographical history, thus resulting in a complex array in biodiversity. Bantimurung Bulusaraung National Park (BabulNP) was gazetted in 2004 to protect the region’s biodiversity and karst ecosystem. However, the park’s herpetofauna is almost unknown. This project consists of three programs: herpetofauna survey in BabulNP, herpetofauna conservation education to local schools, and herpetofauna training for locals and was conducted from July to September 2007. Based on the survey conducted in six sites in the park, we recorded 12 amphibian and 25 reptile species. Five of those species (Bufo celebensis, Rana celebensis, Rhacophorus monticola, Sphenomorphus tropidonotus, and Calamaria muelleri) are endemic to Sulawesi. Two species of the genus Oreophryne are still unidentified. We visited six schools around the park for our herpetofauna conservation education program. The Herpetofauna Observation Training was held over four days with 17 participants from BabulNP staff, local NGOs, school teachers, and Hasanuddin University students. i Conservation of Herpetofauna in Bantimurung Bulusaraung National Park, South Sulawesi, Indonesia Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without the contribution of many persons. We would like to express our gratitude to BP Conservation Leadership Programme for providing funding. -

Species Boundaries, Biogeography, and Intra-Archipelago Genetic Variation Within the Emoia Samoensis Species Group in the Vanuatu Archipelago and Oceania" (2008)

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2008 Species boundaries, biogeography, and intra- archipelago genetic variation within the Emoia samoensis species group in the Vanuatu Archipelago and Oceania Alison Madeline Hamilton Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Recommended Citation Hamilton, Alison Madeline, "Species boundaries, biogeography, and intra-archipelago genetic variation within the Emoia samoensis species group in the Vanuatu Archipelago and Oceania" (2008). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3940. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3940 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. SPECIES BOUNDARIES, BIOGEOGRAPHY, AND INTRA-ARCHIPELAGO GENETIC VARIATION WITHIN THE EMOIA SAMOENSIS SPECIES GROUP IN THE VANUATU ARCHIPELAGO AND OCEANIA A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Biological Sciences by Alison M. Hamilton B.A., Simon’s Rock College of Bard, 1993 M.S., University of Florida, 2000 December 2008 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I thank my graduate advisor, Dr. Christopher C. Austin, for sharing his enthusiasm for reptile diversity in Oceania with me, and for encouraging me to pursue research in Vanuatu. His knowledge of the logistics of conducting research in the Pacific has been invaluable to me during this process. -

Conservation of Amphibians and Reptiles in Indonesia: Issues and Problems

Copyright: © 2006 Iskandar and Erdelen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and repro- Amphibian and Reptile Conservation 4(1):60-87. duction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. DOI: 10.1514/journal.arc.0040016 (2329KB PDF) The authors are responsible for the facts presented in this article and for the opinions expressed there- in, which are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organisation. The authors note that important literature which could not be incorporated into the text has been published follow- ing the drafting of this article. Conservation of amphibians and reptiles in Indonesia: issues and problems DJOKO T. ISKANDAR1 * AND WALTER R. ERDELEN2 1School of Life Sciences and Technology, Institut Teknologi Bandung, 10, Jalan Ganesa, Bandung 40132 INDONESIA 2Assistant Director-General for Natural Sciences, UNESCO, 1, rue Miollis, 75732 Paris Cedex 15, FRANCE Abstract.—Indonesia is an archipelagic nation comprising some 17,000 islands of varying sizes and geologi- cal origins, as well as marked differences in composition of their floras and faunas. Indonesia is considered one of the megadiversity centers, both in terms of species numbers as well as endemism. According to the Biodiversity Action Plan for Indonesia, 16% of all amphibian and reptile species occur in Indonesia, a total of over 1,100 species. New research activities, launched in the last few years, indicate that these figures may be significantly higher than generally assumed. Indonesia is suspected to host the worldwide highest numbers of amphibian and reptiles species. -

Evolutionary History of Spiny- Tailed Lizards (Agamidae: Uromastyx) From

Received: 6 July 2017 | Accepted: 4 November 2017 DOI: 10.1111/zsc.12266 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Evolutionary history of spiny- tailed lizards (Agamidae: Uromastyx) from the Saharo- Arabian region Karin Tamar1 | Margarita Metallinou1† | Thomas Wilms2 | Andreas Schmitz3 | Pierre-André Crochet4 | Philippe Geniez5 | Salvador Carranza1 1Institute of Evolutionary Biology (CSIC- Universitat Pompeu Fabra), Barcelona, The subfamily Uromastycinae within the Agamidae is comprised of 18 species: three Spain within the genus Saara and 15 within Uromastyx. Uromastyx is distributed in the 2Allwetterzoo Münster, Münster, Germany desert areas of North Africa and across the Arabian Peninsula towards Iran. The 3Department of Herpetology & systematics of this genus has been previously revised, although incomplete taxo- Ichthyology, Natural History Museum of nomic sampling or weakly supported topologies resulted in inconclusive relation- Geneva (MHNG), Geneva, Switzerland ships. Biogeographic assessments of Uromastycinae mostly agree on the direction of 4CNRS-UMR 5175, Centre d’Écologie Fonctionnelle et Évolutive (CEFE), dispersal from Asia to Africa, although the timeframe of the cladogenesis events has Montpellier, France never been fully explored. In this study, we analysed 129 Uromastyx specimens from 5 EPHE, CNRS, UM, SupAgro, IRD, across the entire distribution range of the genus. We included all but one of the rec- INRA, UMR 5175 Centre d’Écologie Fonctionnelle et Évolutive (CEFE), PSL ognized taxa of the genus and sequenced them for three mitochondrial and three Research University, Montpellier, France nuclear markers. This enabled us to obtain a comprehensive multilocus time- calibrated phylogeny of the genus, using the concatenated data and species trees. We Correspondence Karin Tamar, Institute of Evolutionary also applied coalescent- based species delimitation methods, phylogenetic network Biology (CSIC-Universitat Pompeu Fabra), analyses and model- testing approaches to biogeographic inferences. -

First Record of the Poorly Known Skink Sphenomorphus Oligolepis (Boulenger, 1914) (Reptilia: Squamata: Scincidae) from Seram Island, Maluku Province, Indonesia

Asian Herpetological Research 2016, 7(1): 64–68 SHORT NOTES DOI: 10.16373/j.cnki.ahr.150052 First Record of the Poorly Known Skink Sphenomorphus oligolepis (Boulenger, 1914) (Reptilia: Squamata: Scincidae) from Seram Island, Maluku Province, Indonesia Sven MECKE1*, Max KIECKBUSCH1, Mark O’SHEA2 and Hinrich KAISER3 1 Department of Animal Evolution and Systematics and Zoological Collection Marburg, Faculty of Biology, Philipps- Universität Marburg, Karl-von-Frisch-Straße 8, 35032 Marburg, Germany 2 Faculty of Science and Engineering, University of Wolverhampton, Wulfruna Street, Wolverhampton, WV1 1LY, United Kingdom; and West Midland Safari Park, Bewdley, Worcestershire DY12 1LF, United Kingdom 3 Department of Biology, Victor Valley College, 18422 Bear Valley Road, Victorville, California 92395, USA; and Department of Vertebrate Zoology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20013, USA Abstract Based on four specimens discovered in the collection of The Natural History Museum, London, United Kingdom, we present a new distribution record for the skink Sphenomorphus oligolepis for Seram Island, Maluku Province, Indonesia. This find constitutes the westernmost record for the species and extends its range by over 800 km. The species was heretofore only known from apparently isolated mainland New Guinean populations. Keywords Scincidae, Lygosominae, Sphenomorphus oligolepis, new record, Seram, Maluku Islands, Indonesia, Wallacea 1. Introduction Massachusetts, USA (MCZ) and the Bernice P. Bishop Museum, Honolulu, Hawaii, USA (BPBM) were Sphenomorphus oligolepis (suggested common name: collected in Gulf Province at Kikori (MCZ R-150879) MIMIKA FOREST SKINK) is a member of the S. and Weiana (MCZ R-101484), and in Morobe Province maindroni group (sensu Greer and Shea, 2004). -

Checklist and Comments on the Terrestrial Reptile Fauna of Kau

area with a complex geologic history. Over the last 40 million Herpetological Review, 2006, 37(2), 167–170. © 2006 by Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles years interplate impact resulted in considerable uplift and volcan- ism and importantly the accretion of at least 32 tectonostratigraphic Checklist and Comments on the Terrestrial terranes along the northern leading edge of the island that have Reptile Fauna of Kau Wildlife Area, Papua New influenced the biodiversity of the region (Pigram and Davies 1987; Guinea Polhemus and Polhemus 1998). To date there has been no comprehensive herpetofaunal reports from the KWA. Here I compile a list of terrestrial reptile species CHRISTOPHER C. AUSTIN present in the KWA based on fieldwork over the past 14 years. Museum of Natural Science, 119 Foster Hall, Louisiana State University Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70803, USA The KWA terrestrial reptile fauna, exclusive of crocodylians and e-mail: [email protected] turtles, currently includes 25 lizards and 7 snakes representing 8 families and 21 genera (Table 1). A similar compilation is under- The island of New Guinea has been identified as a megadiverse way for the amphibians of the region (S. Richards, pers. comm.). region because of its extraordinary biodiversity and highly en- Specific specimen and locality information as well as associated demic biota (Mittermeier and Mittermeier 1997). New Guinea, tissues can be accessed via a searchable database of the LSU Mu- the world’s largest and highest tropical island, occupies less than seum of Natural Science reptile and amphibian collection (http:// 1% of global land area yet 5–7% of the world’s biodiversity is www.lsu.edu/museum). -

Acrodont Iguanians (Squamata) from the Middle Eocene of the Huadian Basin of Jilin Province, China, with a Critique of the Taxon “Tinosaurus冶

第 卷 第 期 古 脊 椎 动 物 学 报 49 摇 1 pp.69-84 年 月 摇 摇 摇 摇 摇 摇 摇 摇 摇 摇 摇 摇 摇 摇 摇 摇 摇 2011 1 VERTEBRATA PALASIATICA 摇 figs.1-5 吉林桦甸盆地中始新世端生齿鬣蜥类 ( 有鳞目) 化石及对响蜥属的评述 1 1 孙 巍2 李春田2 Krister T德. 国S森M肯贝IT格H研究摇所和S自te然p历h史an博物F馆. 古K人. 类S学C与H麦A塞A尔L研究摇 部 法摇兰克福 摇 (1 摇 摇 60325) 吉林大学古生物学与地层学研究中心 长春 (2 摇 摇 130026) 摘要 中国吉林省中始新世桦甸组的两种端生齿鬣蜥类化石突显出端生齿类 在第 : (Acrodonta) 三纪早期的分化 第一种化石的特征为具有多个 个 前侧生齿位及单尖且侧扁的颊齿 。 (6 ) 。 其牙齿与牙齿缺失附尖的主要端生齿类 如鬣蜥亚科 的海蜥属 Hydrosaurus 无特别 ( Agaminae ) 相似之处 其亲缘关系也并不清楚 第二种的牙齿与很多现生有三尖齿的鬣蜥类 即蜡皮蜥 , 。 ( 属 Leiolepis 和飞蜥亚科 以及化石响蜥属的许多种相似 一个骨骼特征显示其可能 Draconinae) ; 与包括鬣蜥亚科 海蜥属 飞蜥亚科和须鬣蜥亚科 的支系有关 但尚需更多 、 、 (Amphibolurinae) , 更完整的标本以做结论 与现生鬣蜥类的比较研究表明 与响蜥属牙齿相似的三尖型齿很可 。 , 能是蜡皮蜥属及飞蜥亚科中大约 个现生种的典型特征 相对于这些支系 响蜥属的鉴定 200 。 , 特征并不充分 由于端生齿类的分化被认为始于新生代早期 因而东亚的化石材料很可能有 。 , 助于阐明这一支系的演化历史 尤其是结合分子遗传学的研究方法 然而仅基于破碎颌骨材 , 。 料的新分类单元名称的成倍增加并不能使我们更接近这一目标 尽力采集标本并研究可对比 , 的现生骨骼材料应是第一位的 。 关键词 中国吉林 始新世 桦甸组 端生齿类 鬣蜥科 响蜥属 衍征 : ; ; ; ; ; ; 中图法分类号 文献标识码 文章编号 :Q915. 864摇 :A摇 :1000-3118(2011)01-0069-16 ACRODONT IGUANIANS (SQUAMATA) FROM THE MIDDLE EOCENE OF THE HUADIAN BASIN OF JILIN PROVINCE, CHINA, WITH A CRITIQUE OF THE TAXON “TINOSAURUS冶 1 1 2 2 DepartmKenrtisoftePralTae.oaSnMthrIoTpHolog摇y aSntdepMheassnel FRe.seKa.rcShCSHenAckAenLber摇g RSeUseaNrchWInesitit摇uteLaIndCNhuatnu鄄raTliaHnistory Museum (1 , 摇 Senckenberganlage 25, 60325 Frankfurt am Main, Germany摇 krister. smith@ senckenberg. de) Research Center for Paleontology and Stratigraphy Jilin University (2 , Changchun 130026, China) Abstract 摇 Two acrodont iguanians from the middle Eocene Huadian Formation, Jilin Province, China, highlight the diversity of Acrodonta early in the Tertiary. The first is characterized by a high number (six) of anterior pleurodont tooth loci and by unicuspid, labiolingually compressed cheek teeth. These teeth, however, show noHsypdercoisaalusriumsilarity to those of major acrodontan clades in which the accessory cusps are absent (e. -

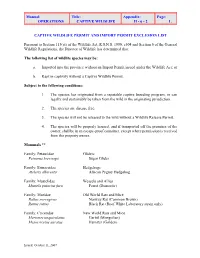

Captive Wildlife Exclusion List

Manual: Title: Appendix: Page: OPERATIONS CAPTIVE WILDLIFE II - 6 - 2 1. CAPTIVE WILDLIFE PERMIT AND IMPORT PERMIT EXCLUSION LIST Pursuant to Section 113(at) of the Wildlife Act, R.S.N.S. 1989, c504 and Section 6 of the General Wildlife Regulations, the Director of Wildlife has determined that: The following list of wildlife species may be: a. Imported into the province without an Import Permit issued under the Wildlife Act; or b. Kept in captivity without a Captive Wildlife Permit. Subject to the following conditions: 1. The species has originated from a reputable captive breeding program, or can legally and sustainably be taken from the wild in the originating jurisdiction. 2. The species are disease free. 3. The species will not be released to the wild without a Wildlife Release Permit. 4. The species will be properly housed, and if transported off the premises of the owner, shall be in an escape-proof container, except where permission is received from the property owner. Mammals ** Family: Petauridae Gliders Petuarus breviceps Sugar Glider Family: Erinaceidae Hedgehogs Atelerix albiventis African Pygmy Hedgehog Family: Mustelidae Weasels and Allies Mustela putorius furo Ferret (Domestic) Family: Muridae Old World Rats and Mice Rattus norvegicus Norway Rat (Common Brown) Rattus rattus Black Rat (Roof White Laboratory strain only) Family: Cricetidae New World Rats and Mice Meriones unquiculatus Gerbil (Mongolian) Mesocricetus auratus Hamster (Golden) Issued: October 11, 2007 Manual: Title: Appendix: Page: OPERATIONS CAPTIVE WILDLIFE II - 6 - 2 2. Family: Caviidae Guinea Pigs and Allies Cavia porcellus Guinea Pig Family: Chinchillidae Chinchillas Chincilla laniger Chinchilla Family: Leporidae Hares and Rabbits Oryctolagus cuniculus European Rabbit (domestic strain only) Birds Family: Psittacidae Parrots Psittaciformes spp.* All parrots, parakeets, lories, lorikeets, cockatoos and macaws. -

Conservation of Amphibians and Reptiles in Indonesia: Issues and Problems

Copyright: © 2006 Iskandar and Erdelen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and repro- Amphibian and Reptile Conservation 4(1):60-87. duction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. DOI: 10.1514/journal.arc.0040016 (2329KB PDF) The authors are responsible for the facts presented in this article and for the opinions expressed there- in, which are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organisation. The authors note that important literature which could not be incorporated into the text has been published follow- ing the drafting of this article. Conservation of amphibians and reptiles in Indonesia: issues and problems DJOKO T. ISKANDAR1 * AND WALTER R. ERDELEN2 1School of Life Sciences and Technology, Institut Teknologi Bandung, 10, Jalan Ganesa, Bandung 40132 INDONESIA 2Assistant Director-General for Natural Sciences, UNESCO, 1, rue Miollis, 75732 Paris Cedex 15, FRANCE Abstract.—Indonesia is an archipelagic nation comprising some 17,000 islands of varying sizes and geologi- cal origins, as well as marked differences in composition of their floras and faunas. Indonesia is considered one of the megadiversity centers, both in terms of species numbers as well as endemism. According to the Biodiversity Action Plan for Indonesia, 16% of all amphibian and reptile species occur in Indonesia, a total of over 1,100 species. New research activities, launched in the last few years, indicate that these figures may be significantly higher than generally assumed. Indonesia is suspected to host the worldwide highest numbers of amphibian and reptile species. -

Biosynthetic Products for Cancer Chemotherapy Volume} Biosynthetic Products for Cancer Chemotherapy Volume}

Biosynthetic Products for Cancer Chemotherapy Volume} Biosynthetic Products for Cancer Chemotherapy Volume} George R. Pettit Arizona State University, Tempe PLENUM PRESS· NEW YORK AND LONDON Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Pettit, George R Biosynthetic products for cancer chemotherapy. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Cancer-Chemotherapy. 2. Antineoplastic agents. I. Title [DNLM: 1. Neo plasms-Drug therapy. 2. Antineoplastic agents. QZ267 PSllb] RC271.CSP47 616.9'94'061 76-S4146 ISBN-13: 978-1-4684-7232-S e-ISBN-13: 978-1-4684-7230-1 001: 10.1007/978-1-4684-7230-1 © 1977 Plenum Press, New York Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1977 A Division of Plenum Publishing Corporation 227 West 17th Street, New York, N.Y. 10011 All righ ts reserved No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microf"llming, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the Publisher To the far-sighted. enlightened and dedicated present and past members of the National Cancer Institute whose great contributions and personal sacrifice have provided a firm basis for cancer chemotherapy and eventual control of human cancer. Preface Cancer exacts an incredibly destructive toll on the world's human populations. In recent years we have frequently heard the expression "war on cancer," but compared to the carnage inflicted by cancer, our scientific and medical efforts, to date, would seem more like a minor skirmish. Some comprehension of the cancer problem can be obtained from a look at the current and projected casualty list for the United States. -

Species Richness in Time and Space: a Phylogenetic and Geographic Perspective

Species Richness in Time and Space: a Phylogenetic and Geographic Perspective by Pascal Olivier Title A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ecology and Evolutionary Biology) in The University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Assistant Professor and Assistant Curator Daniel Rabosky, Chair Associate Professor Johannes Foufopoulos Professor L. Lacey Knowles Assistant Professor Stephen A. Smith Pascal O Title [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-6316-0736 c Pascal O Title 2018 DEDICATION To Judge Julius Title, for always encouraging me to be inquisitive. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The research presented in this dissertation has been supported by a number of research grants from the University of Michigan and from academic societies. I thank the Society of Systematic Biologists, the Society for the Study of Evolution, and the Herpetologists League for supporting my work. I am also extremely grateful to the Rackham Graduate School, the University of Michigan Museum of Zoology C.F. Walker and Hinsdale scholarships, as well as to the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Block grants, for generously providing support throughout my PhD. Much of this research was also made possible by a Rackham Predoctoral Fellowship, and by a fellowship from the Michigan Institute for Computational Discovery and Engineering. First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Dan Rabosky, for taking me on as one of his first graduate students. I have learned a tremendous amount under his guidance, and conducting research with him has been both exhilarating and inspiring. I am also grateful for his friendship and company, both in Ann Arbor and especially in the field, which have produced experiences that I will never forget.