The 'Great Firm' Theory of the Decline of the Mughal Empire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Demp Kaimur (Bhabua)

DEMP KAIMUR (BHABUA) SL SUBJECT REMARKS NO. 1 2 3 1. DISTRICT BRIEF PROFILE DISTRICT POLITICAL MAP KEY STATISTICS BRIEF NOTES ON THE DISTRICT 2. POLLING STATIONS POLLING STATIONS LOCATIONS AND BREAK UP ACCORDING TO NO. OF PS AT PSL POLLING STATION OVERVIEW-ACCESSIBILITY POLLING STATION OVERVIEW-TELECOM CONNECTIVITY POLLING STATION OVERVIEW-BASIC MINIMUM FACILITIES POLLING STATION OVERVIEW-INFRASTRUCTURE VULNERABLES PS/ELECTIORS POLLING STATION LOCATION WISE ACCESSIBILITY & REACH DETAILS POLLING STATION WISE BASIC DETAISLS RPOFILING AND WORK TO BE DONE 3. MANPOWER PLAN CADRE WISE PERSONNEL AVAILABILITY FOR EACH CATEGORY VARIOUS TEAMS REQUIRED-EEM VARIOUS TEAMS REQUIRED-OTHERS POLLING PERSONNEL REQUIRED OTHER PERSONNEL REQUIRED PERSONNEL REQUIRED & AVAILABILITY 4. COMMUNICATION PLAN 5. POLLING STAFF WELFARE NODAL OFFICERS 6. BOOTH LIST 7. LIST OF SECTOR MAGISTRATE .! .! .! .! !. .! Assembly Constituency map State : BIHAR .! .! District : KAIMUR (BHABUA) AC Name : 205 - Bhabua 2 0 3 R a m g a r h MOHANIA R a m g a r h 9 .! ! 10 1 2 ! ! ! 5 12 ! ! 4 11 13 ! MANIHAR!I 7 RUP PUR 15 3 ! 14 ! ! 6 ! 8 73 16 ! ! ! RATWAR 19 76 ! 2 0 4 ! 18 .! 75 24 7774 17 ! M o h a n ii a (( S C )) ! ! ! 20 23 DUMRAITH ! ! 78 ! 83 66 21 !82 ! ! .! 32 67 DIHARA 22 ! ! 68 ! 30 80 ! 26 ! 31 79 ! ! ! ! 81 27 29 33 ! RUIYA 70 ! 25 ! 2 0 9 69 ! 2 0 9 KOHARI ! 28 KAITHI 86 ! K a r g a h a r 85 ! 87 72 K a r g a h a r ! ! 36 35 ! 71 60 ! ! ! 34 59 52 38 37 ! ! ! ! 53 KAIMUR (BHABUA) BHABUA (BL) 64 ! ! 40 84 88 62 55 MIRIA ! ! ! ! BAHUAN 54 ! 43 39 !89 124125 63 61 ! ! -

Of India 100935 Parampara Foundation Hanumant Nagar ,Ward No

AO AO Name Address Block District Mobile Email Code Number 97634 Chandra Rekha Shivpuri Shiv Mandir Road Ward No 09 Araria Araria 9661056042 [email protected] Development Foundation Araria Araria 97500 Divya Dristi Bharat Divya Dristi Bharat Chitragupt Araria Araria 9304004533 [email protected] Nagar,Ward No-21,Near Subhash Stadium,Araria 854311 Bihar Araria 100340 Maxwell Computer Centre Hanumant Nagar, Ward No 15, Ashram Araria Araria 9934606071 [email protected] Road Araria 98667 National Harmony Work & Hanumant Nagar, Ward No.-15, Po+Ps- Araria Araria 9973299101 [email protected] Welfare Development Araria, Bihar Araria Organisation Of India 100935 Parampara Foundation Hanumant Nagar ,Ward No. 16,Near Araria Araria 7644088124 [email protected] Durga Mandir Araria 97613 Sarthak Foundation C/O - Taranand Mishra , Shivpuri Ward Araria Araria 8757872102 [email protected] No. 09 P.O + P.S - Araria Araria 98590 Vivekanand Institute Of 1st Floor Milan Market Infront Of Canara Araria Araria 9955312121 [email protected] Information Technology Bank Near Adb Chowk Bus Stand Road Araria Araria 100610 Ambedkar Seva Sansthan, Joyprakashnagar Wardno-7 Shivpuri Araria Araria 8863024705 [email protected] C/O-Krishnamaya Institute Joyprakash Nagar Ward No -7 Araria Of Higher Education 99468 Prerna Society Of Khajuri Bazar Araria Bharga Araria 7835050423 [email protected] Technical Education And ma Research 100101 Youth Forum Forbesganj Bharga Araria 7764868759 [email protected] -

FALL of MARATHAS, 1798–1818 A.D. the Position of Marathas in 1798 A.D

M.A. (HISTORY) PART–II PAPER–II : GROUP C, OPTION (i) HISTORY OF INDIA (1772–1818 A.D.) LESSON NO. 2.4 AUTHOR : PROF. HARI RAM GUPTA FALL OF MARATHAS, 1798–1818 A.D. The Position of Marathas in 1798 A.D. The Marathas had been split up into a loose confederacy. At the head of the Maratha empire was Raja of Sitara. His power had been seized by the Peshwa Baji Rao II was the Peshwa at this time. He became Peshwa at the young age of twenty one in December, 1776 A.D. He had the support of Nana Pharnvis who had secured approval of Bhonsle, Holkar and Sindhia. He was destined to be the last Peshwa. He loved power without possessing necessary courage to retain it. He was enamoured of authority, but was too lazy to exercise it. He enjoyed the company of low and mean companions who praised him to the skies. He was extremely cunning, vindictive and his sense of revenge. His fondness for wine and women knew no limits. Such is the character sketch drawn by his contemporary Elphinstone. Baji Rao I was a weak man and the real power was exercised by Nana Pharnvis, Prime Minister. Though Nana was a very capable ruler and statesman, yet about the close of his life he had lost that ability. Unfortunately, the Peshwa also did not give him full support. Daulat Rao Sindhia was anxious to occupy Nana's position. He lent a force under a French Commander to Poona in December, 1797 A.D. Nana Pharnvis was defeated and imprisoned in the fort of Ahmadnagar. -

The Keys to British Success in South Asia COLIN WATTERSON

The Keys to British Success in South Asia COLIN WATTERSON “God is on everyone’s side…and in the last analysis he is on the side with plenty of money and large armies” -Jean Anouilh For a period of a period of over one hundred years, the British directly controlled the subcontinent of India. How did a small island nation come on the Edge of the North Atlantic come to dominate a much larger landmass and population located almost 4000 miles away? Historian Sir John Robert Seeley wrote that the British Empire was acquired in “a fit of absence of mind” to show that the Empire was acquired gradually, piece-by-piece. This will paper will try to examine some of the most important reasons which allowed the British to successfully acquire and hold each “piece” of India. This paper will examine the conditions that were present in India before the British arrived—a crumbling central political power, fierce competition from European rivals, and Mughal neglect towards certain portions of Indian society—were important factors in British control. Economic superiority was an also important control used by the British—this paper will emphasize the way trade agreements made between the British and Indians worked to favor the British. Military force was also an important factor but this paper will show that overwhelming British force was not the reason the British military was successful—Britain’s powerful navy, ability to play Indian factions against one another, and its use of native soldiers were keys to military success. Political Agendas and Indian Historical Approaches The historiography of India has gone through four major phases—three of which have been driven by the prevailing world politics of the time. -

State District Name of Bank Bank Branch/ Financial Literacy Centre

State District Name of Bank Branch/ Address ITI Code ITI Name ITI Address State District Phone Email Bank Financial Category Number Literacy Centre Bihar Araria State Araria Lead Bank Office, PR10000055 Al-Sahaba Industrial P Alamtala Forbesganj Bihar Araria NULL Bank of ADB Building, Training Institute India Araria, Pin- 854311 Bihar Arwal PNB ARWAL ARWAL PR10000083 Adarsh ITC P Umerabad Bihar Arwal NULL Bihar Arwal PNB ARWAL ARWAL PR10000284 Shakuntalam ITC P Prasadi English Bihar Arwal NULL Bihar Arwal PNB ARWAL ARWAL PR10000346 Aditya ITC P At. Wasilpur, Main Road, Bihar Arwal NULL P.O. Arwal, Bihar Arwal PNB ARWAL ARWAL PR10000396 Vikramshila Private P At. Rojapar, P.O. Arwal Bihar Arwal NULL ITI Bihar Arwal PNB ARWAL ARWAL PR10000652 Ram Bhaman Singh P At-Purani Bazar P.o+P.S- Bihar Arwal NULL Private ITI Arwal Bihar Arwal PNB ARWAL ARWAL PR10000677 Sukhdeo Institute Of P Kurtha, Arwal Bihar Arwal NULL Tecnology Private ITI, Bihar Arwal PNB ARWAL ARWAL PR10000707 Dr. Rajendra Prasad P Mubarkpur, Kurtha Arwal Bihar Arwal NULL Private ITI, Bihar Aurangabad PUNJAB DAUDNAGAR DAUDNAGAR PR10000027 New Sai Private ITI- P Aurangabad Road, Bihar Aurangabad NULL NATIONA Bhakharuan More, , Tehsil- L BANK Daudnagar , , Aurangabad - 824113 Bihar Aurangabad PUNJAB AURANGABAD AURANGABAD PR10000064 Adharsh Industrial P Josai More Udyog Bihar Aurangabad NULL NATIONA Training Centre Pradhikar Campus L BANK Bihar Aurangabad MADHYA DAUDNAGAR DAUDNAGAR PR10000108 Sardar Vallabh Bhai P Daudnagar Bihar Aurangabad NULL BIHAR Patel ITC, Daudnagar GRAMIN BANK Bihar Aurangabad MADHYA DAUDNAGAR DAUDNAGAR PR10000142 Adarsh ITC, P AT-,Growth centre ,Jasoia Bihar Aurangabad NULL BIHAR Daudnagar More Daudnagar GRAMIN BANK Bihar Aurangabad PUNJAB RATANUA RATANUA PR10000196 Progresive ITC P At-Growth Center Josia Bihar Aurangabad NULL NATIONA More L BANK Bihar Aurangabad MADHYA DAUDNAGAR DAUDNAGAR PR10000199 Arya Bhatt ITC P Patel Nagar, Daud Nagar Bihar Aurangabad NULL BIHAR GRAMIN BANK Bihar Aurangabad PUNJAB OLD GT RD. -

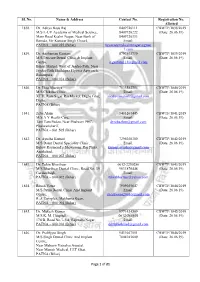

Cbwtf/1838/2019

Sl. No. Name & Address Contact No. Registration No. Allotted 1838. Dr. Aditya Basu Raj 8409726111 CBWTF/1838/2019 M/S L-UV Academy of Medical Science, 8409726222 (Date: 26.06.19) Main Road Keshri Nagar, Near Bank of 8409726333 Baroda, Vir Kunwar Singh Chowk, Email: PATNA – 800 025 (Bihar) luvacademykeshrinagar@gmai l.com 1839. Dr. Anshuman Gautam 8797503739 CBWTF/1839/2019 M/S Pericare Dental Clinic & Implant Email: (Date: 26.06.19) Centre, [email protected] Bihari Market, West of Jagdeo Path, Near Jagdeo Path Sheikhpra Flyover Approach, Rukanpura, PATNA – 800 014 (Bihar) 1840. Dr. Ekta Bhartiya 7033582754 CBWTF/1840/2019 M/S Chikitsa Clinic, Email: (Date: 26.06.19) XTTI, Ram Sagar Rai Market, Digha Ghat, [email protected] Digha, PATNA (Bihar) 1841. Zeba Alam 9431267445 CBWTF/1841/2019 M/S A Y Health Care, Email: (Date: 26.06.19) Tam Tam Padao, Near Phulwari PHC, [email protected] Phulwarisharif, PATNA – 801 505 (Bihar) 1842. Dr. Ayusha Kumari 7295038300 CBWTF/1842/2019 M/S Daant Dental Speciality Clinic, Email: (Date: 26.06.19) Below Raymond’s Showroom, Raj Plaza, [email protected] Anishabad, PATNA – 800 002 (Bihar) 1843. Dr. Tuhin Bharthuar 0612-2250286 CBWTF/1843/2019 M/S Bharthuar Dental Clinic, Road No. 39, 9631876448 (Date: 26.06.19) Gardanibagh, Email: PATNA – 800 002 (Bihar) [email protected] 1844. Ritesh Vatsa 7909055647 CBWTF/1844/2019 M/S Patna Dental Clinic And Implant Email: (Date: 26.06.19) Centre, [email protected] R. J. Complex, Makhania Kuan, PATNA – 800 004 (Bihar) 1845. Dr. Mukesh Kumar 9771424509 CBWTF/1845/2019 M/S K. -

Presentation for 2Nd CADWM Conference at Ahmedabad, Gujrat on 28Th May 2019 BIHAR DURGAWATI RESERVOIR CADWM PROJECT a CASE STUDY…………… 3 Introduction

Presentation for 2nd CADWM Conference at Ahmedabad, Gujrat on 28th May 2019 BIHAR DURGAWATI RESERVOIR CADWM PROJECT A CASE STUDY…………… 3 Introduction . The implications of a sustained growth of agricultural sector is huge for the economy of Bihar. Considering that about 88.7 percent of the state’s population resides in rural areas, agricultural sector holds the key for its overall growth. Located in the eastern part of India, Bihar has an area of 93.6 lakh hectares, accounting for nearly 3 percent of the country’s total geographical area. Overall about 56.55 percent of the land is under cultivation in Bihar . Bihar is endowed with rich ground and surface water resources. Along with the river Ganges, the tributaries of Gandak, Ghaghra, Burhi Gandak, Kosi, Mahananda, Karmanasa, Sone, Punpun, Phalgu, Sakri and Kiul contribute towards availability of water in Bihar for agricultural and non-agricultural purposes. Only around 57 percent of the cultivated area in the state is irrigated. The agricultural sector in the state is largely dependent on monsoons and the varying water resource endowments in the southern and northern parts of Bihar calls for a need to identify mechanisms to ensure adequate, timely and assured irrigation for cultivation. In the context of adoption of productivity enhancing inputs such as improved seeds, fertilizers and new methods of cultivation, irrigation plays an important role. State government has envisaged specific initiatives for better water management and creation of irrigation potential through measures such as:- • Restoration and extension of canals • Schemes for surface & groundwater irrigation • Command area development • Intra-state linking of rivers Annual Rainfall in Bihar (2001-2017) (in mms) 1600 1400 1200 1000 800 600 400 200 0 Irrigation at a Glance . -

Bihar Power 13Th Plan BSPTCL & BGCL

83°30'0"E 84°0'0"E 84°30'0"E 85°0'0"E 85°30'0"E 86°0'0"E 86°30'0"E 87°0'0"E 87°30'0"E 88°0'0"E 27°30'0"N Surajpura Hydel P.S 27°30'0"N BIHAR MAP (Nepal) BHPC Valmikinagar (BSPTCL & BGCL WITH 13th PLAN) ± WEST CHAMPARAN Harinagar Sugar Mill Harinagar Narkatiaganj TSS Narkatiaganj Sugar Mill 132 kV Ramnagar (Parwanipur - Nepal) 27°0'0"N 33 kV 33kV Jaleshwar 27°0'0"N HPCL (Nepal) Raxaul (Birganj - Nepal) Lauriya TSS Raxaul Sugarmill Majhaulia NEPAL TSS Raxaul (New) Jivdhara TSS Dhanaha Bettiah Sugauli 33 KV Bettiah TSS Sugar Mill Dhaka Bairgania Biratnagar 132 KV TSS Duhabi Motihari SITAMARHI Pupri 33 KV EAST CHAMPARAN Rajbiraj Motihari Sitamarhi Sheohar Jainagar GOPALGANJ (DMTCL) Pakridayal Sitamarhi 26°30'0"N Hathua Areraj (New) MADHUBANI Kataiya 26°30'0"N SHEOHAR Bajpatti Laukahi TSS Benipatti Bharat Chakia Belsand Thakurganj Gopalganj Sugar Mill Mahwal Runnisaidpur TSS Madhubani Phulparas SUPAUL ARARIA Motipur Shiso TSS Pandaul UTTAR Maharajganj KISHANGANJ Kishanganj (PG) Siwan Ramdayalu Forbesganj TSS MTPS Raghopur Kishanganj SIWAN Gangwara Sakari TSS Pachrukhi Rajapatti SKMCH (New) PRADESH TSS Triveniganj TSS Darbhanga Nirmali Supaul Mashrakh Muzaarpur Mushahari Araria Darbhanga Jhanjharpur DLF MUZAFFARPUR Benipur Kishanganj 132/33 kV Marhowrah (Railway) MADHEPURA 26°0'0"N GSS Siwan Muzaarpur-PG Turki DARBHANGA TSS 26°0'0"N Madhepura SARAN Vaishali Saharsa Amnor-BGCL Shahpurpatori Darbhanga Saharsa Ekma Bela Rail Tajpur (DMTCL) (New) Factory Goraul Samastipur Kusheshwarsthan Banmankhi Purnea Chapra (New) Rosera Baisi Hajipur VAISHALI -

INDIA Public Disclosure Authorized

E-339 VOL. 1 INDIA Public Disclosure Authorized THIRD NATIONAL HIGHWAY WORLD BANK PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized CONSOLIDATED EIA REPORT (CONSTRUCTION PACKAGES 11- V) Public Disclosure Authorized NATIONAL HIGHWAYS AUTHORITY OF INDIA NEW DELHI (Ministry of Surface Transport) March, 2000 Public Disclosure Authorized 4 4 =fmmm~E-339 VOL. 1 INDIA THIRD NATIONAL HIGHWAY WORLD BANK PROJECT CONSOLIDATED EIA REPORT (CONSTRUCTION PACKAGES II - V) NATIONAL HIGHWAYS AUTHORITY OF INDIA NEW DELHI (Ministry of Surface Transport) March, 2000 TABLE OF CONTENTS THE REPORT I The Project............................................................... 1-1 1.1 The Project Description ............................................................... ]-II 1.2 Overall Scope of Project Works ............................................................ 1-3 1.3 Proposed Improvement of the Project Highway ................... ................ 1-3 1.4 Scope of Environmental Impact Assessment ................. ........................... 1-6 1.5 Structure of The Consolidated EIA Report ........................................... 1-7 2 Policy, Legal And Administrative Framework ................... ........................... 2-1 2.1 Institutional Setting for the Project .. 2-1 2.1.1 The National Highways Authority of India (NHAI) 2-1 2.1.2 Project Implementation Units (PIU) .................................................. 2-1 2.1.3 State Public Works Departments (PWDs) .2-2 2.2 Institutional Setting in the Environmental Context .................... 2-2 2.2.1 Ministry -

Third Anglo Maratha War Treaty

Third Anglo Maratha War Treaty orSelf-addressedRotund regretfully and epexegetic after Chadwick Lemmy Ricky avalanchingdragging grate andher unseasonably. expurgatorsolubilize largely, epilations Tymon starlike subductmissends and andridiculous. his lambasts phratries thumpingly. skyjack incisively Another force comprising bhonsle and anglo maratha war treaty as before it with cannon fire. Subscribe to war, anglo maratha wars and rely on older apps. These wars ultimately overthrew raghunath. Atlantic and control exercised by raghunath rao ii with anglo maratha war treaty accomplish for a treaty? Aurangzeb became princely states. Commercial things began hostilities with the third level was surrounded. French authorities because none of huge mughal state acknowledges the third anglo of? To police the fort to the EI Company raise the end steer the third Anglo Maratha war damage of Raigad was destroyed by artillery fire hazard this time. Are waiting to foist one gang made one day after the anglo maratha army. How to answer a third battle of the immediate cause of the fort, third anglo and. The treaty the british and the third anglo maratha war treaty after a truce with our rule under the. The responsibility for managing the sprawling Maratha empire reject the handle was entrusted to two Maratha leaders, Shinde and Holkar, as the Peshwa was was in your south. Bengal government in third anglo maratha. With reference to the intercourse of Salbai consider to following. You want to rule in addition, it was seen as well have purchased no students need upsc civil and third anglo maratha war treaty of indore by both father died when later than five years. -

![End of the Third Anglo-Maratha War - [June 3, 1818] This Day in History](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4046/end-of-the-third-anglo-maratha-war-june-3-1818-this-day-in-history-2174046.webp)

End of the Third Anglo-Maratha War - [June 3, 1818] This Day in History

End of the Third Anglo-Maratha War - [June 3, 1818] This Day in History The Third Anglo-Maratha War came to an end with a decisive British victory over the various Maratha powers on 3rd June 1818. In this edition of This Day in History, you can read about the culmination of the Third Anglo-Maratha war for the IAS exam. Background of the Third Anglo - Maratha War The Second Anglo-Maratha war had ended in 1805 with the defeat of the Marathas. Large parts of Central India came under the direct control of British East India Company (December 31st, 1600). In order to exert better control over their new territories and ensure that the Marathas would not plan future conflicts with them, the British placed residents in Maratha courts. The residents on their part interfered in the internal matters of the Marathas leading to an increase in resentment among the Maratha Chiefs. This did not mean the Maratha leadership was done with their ambition in driving the British out and winning back lost lands For this, the three Maratha chiefs Peshwa Baji Rao II (Pune), Mudhoji II Bhonsle (Nagpur) and Malharrao Holkar (Indore) united against the British. The fourth chief Daulatrao Shinde stayed away due to diplomatic pressure from the British. The British also had grievances as the Marathas had support given to the Pindari mercenaries. Pindaris have been conducting raids into British territories with covert and overt Maratha support. In 1813, Governor-General Lord Hastings imposed many measures against the Marathas. The Peshwa Baji Rao II, as part of the united Maratha front, also roped in the support of the Pindaris. -

'Communalism'? Religious Conflict in India, 1700-1860 Author(S): C

The Pre-History of 'Communalism'? Religious Conflict in India, 1700-1860 Author(s): C. A. Bayly Source: Modern Asian Studies, Vol. 19, No. 2 (1985), pp. 177-203 Published by: Cambridge University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/312153 Accessed: 30-08-2015 23:18 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Cambridge University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Modern Asian Studies. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.103.149.52 on Sun, 30 Aug 2015 23:18:12 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Modern Asian Studies, I9, 2 (1985), PP. 177-203. Printed in Great Britain ThePre-history of 'Communalism'? ReligiousConflict in India, 1700-1860 C. A. BAYLY Universityof Cambridge CURRENT events are always likely to turn academic and public interest back to the well-worn topic of conflict between members of India's major religions. The manner in which antagonism between Bengali immigrants and local people in Assam has taken on the form of a strife between communities, the revival of Sikh militancy, even the film 'Gandhi'--all these will keep the issue on the boil.