Essays on Regulation of Media, Entertainment, and Telecommunications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Media Self-Regulation Guidebook

The Media Self-Regulation Guidebook All questions and answers The Representative on Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe Freedom of the Media The OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media wishes to thank the Governments of France, Germany and Ireland for their generous support to this publication. We would also like to extend our gratitude to Robert Pinker, Peter Stuber and the AIPCE members for their invaluable contributions to this project. The views expressed by the authors in this publication are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media. Published by Miklós Haraszti, the OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media Edited by Adeline Hulin and Jon Smith © 2008 Office of the Representative on Freedom of the Media Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) Wallnerstrasse 6 A-1010 Vienna, Austria Tel.: +43-1 514 36 68 00 Fax: +43-1 514 36 6802 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.osce.org/fom Design & Layout: Phoenix Design Aid, Denmark ISBN 3-9501995-7-2 The Media Self-Regulation Guidebook All questions and answers The OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media Miklós Haraszti Vienna 2008 CONTENTS Contents 7 Miklós Haraszti Foreword 9 I. The merits of media self-regulation Balancing rights and responsibilities By Miklós Haraszti 10 1. The nature of media self-regulation 13 2. Media self-regulation versus regulating the media 18 3. The promotion of mutual respect and cultural understanding 21 II. Setting up a journalistic code of ethics The core of media self-regulation By Yavuz Baydar 22 1. -

Federal Communications Commission Before the Federal

Federal Communications Commission Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Existing Shareholders of Clear Channel ) BTCCT-20061212AVR Communications, Inc. ) BTCH-20061212CCF, et al. (Transferors) ) BTCH-20061212BYE, et al. and ) BTCH-20061212BZT, et al. Shareholders of Thomas H. Lee ) BTC-20061212BXW, et al. Equity Fund VI, L.P., ) BTCTVL-20061212CDD Bain Capital (CC) IX, L.P., ) BTCH-20061212AET, et al. and BT Triple Crown Capital ) BTC-20061212BNM, et al. Holdings III, Inc. ) BTCH-20061212CDE, et al. (Transferees) ) BTCCT-20061212CEI, et al. ) BTCCT-20061212CEO For Consent to Transfers of Control of ) BTCH-20061212AVS, et al. ) BTCCT-20061212BFW, et al. Ackerley Broadcasting – Fresno, LLC ) BTC-20061212CEP, et al. Ackerley Broadcasting Operations, LLC; ) BTCH-20061212CFF, et al. AMFM Broadcasting Licenses, LLC; ) BTCH-20070619AKF AMFM Radio Licenses, LLC; ) AMFM Texas Licenses Limited Partnership; ) Bel Meade Broadcasting Company, Inc. ) Capstar TX Limited Partnership; ) CC Licenses, LLC; CCB Texas Licenses, L.P.; ) Central NY News, Inc.; Citicasters Co.; ) Citicasters Licenses, L.P.; Clear Channel ) Broadcasting Licenses, Inc.; ) Jacor Broadcasting Corporation; and Jacor ) Broadcasting of Colorado, Inc. ) ) and ) ) Existing Shareholders of Clear Channel ) BAL-20070619ABU, et al. Communications, Inc. (Assignors) ) BALH-20070619AKA, et al. and ) BALH-20070619AEY, et al. Aloha Station Trust, LLC, as Trustee ) BAL-20070619AHH, et al. (Assignee) ) BALH-20070619ACB, et al. ) BALH-20070619AIT, et al. For Consent to Assignment of Licenses of ) BALH-20070627ACN ) BALH-20070627ACO, et al. Jacor Broadcasting Corporation; ) BAL-20070906ADP CC Licenses, LLC; AMFM Radio ) BALH-20070906ADQ Licenses, LLC; Citicasters Licenses, LP; ) Capstar TX Limited Partnership; and ) Clear Channel Broadcasting Licenses, Inc. ) Federal Communications Commission ERRATUM Released: January 30, 2008 By the Media Bureau: On January 24, 2008, the Commission released a Memorandum Opinion and Order(MO&O),FCC 08-3, in the above-captioned proceeding. -

Radio Stations in Michigan Radio Stations 301 W

1044 RADIO STATIONS IN MICHIGAN Station Frequency Address Phone Licensee/Group Owner President/Manager CHAPTE ADA WJNZ 1680 kHz 3777 44th St. S.E., Kentwood (49512) (616) 656-0586 Goodrich Radio Marketing, Inc. Mike St. Cyr, gen. mgr. & v.p. sales RX• ADRIAN WABJ(AM) 1490 kHz 121 W. Maumee St. (49221) (517) 265-1500 Licensee: Friends Communication Bob Elliot, chmn. & pres. GENERAL INFORMATION / STATISTICS of Michigan, Inc. Group owner: Friends Communications WQTE(FM) 95.3 MHz 121 W. Maumee St. (49221) (517) 265-9500 Co-owned with WABJ(AM) WLEN(FM) 103.9 MHz Box 687, 242 W. Maumee St. (49221) (517) 263-1039 Lenawee Broadcasting Co. Julie M. Koehn, pres. & gen. mgr. WVAC(FM)* 107.9 MHz Adrian College, 110 S. Madison St. (49221) (517) 265-5161, Adrian College Board of Trustees Steven Shehan, gen. mgr. ext. 4540; (517) 264-3141 ALBION WUFN(FM)* 96.7 MHz 13799 Donovan Rd. (49224) (517) 531-4478 Family Life Broadcasting System Randy Carlson, pres. WWKN(FM) 104.9 MHz 390 Golden Ave., Battle Creek (49015); (616) 963-5555 Licensee: Capstar TX L.P. Jack McDevitt, gen. mgr. 111 W. Michigan, Marshall (49068) ALLEGAN WZUU(FM) 92.3 MHz Box 80, 706 E. Allegan St., Otsego (49078) (616) 673-3131; Forum Communications, Inc. Robert Brink, pres. & gen. mgr. (616) 343-3200 ALLENDALE WGVU(FM)* 88.5 MHz Grand Valley State University, (616) 771-6666; Board of Control of Michael Walenta, gen. mgr. 301 W. Fulton, (800) 442-2771 Grand Valley State University Grand Rapids (49504-6492) ALMA WFYC(AM) 1280 kHz Box 669, 5310 N. -

We Are All Rwandans”

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles “We are all Rwandans”: Imagining the Post-Genocidal Nation Across Media A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Television by Andrew Phillip Young 2016 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION “We are all Rwandans”: Imagining the Post-Genocidal Nation Across Media by Andrew Phillip Young Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Television University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Chon A. Noriega, Chair There is little doubt of the fundamental impact of the 1994 Rwanda genocide on the country's social structure and cultural production, but the form that these changes have taken remains ignored by contemporary media scholars. Since this time, the need to identify the the particular industrial structure, political economy, and discursive slant of Rwandan “post- genocidal” media has become vital. The Rwandan government has gone to great lengths to construct and promote reconciliatory discourse to maintain order over a country divided along ethnic lines. Such a task, though, relies on far more than the simple state control of media message systems (particularly in the current period of media deregulation). Instead, it requires a more complex engagement with issues of self-censorship, speech law, public/private industrial regulation, national/transnational production/consumption paradigms, and post-traumatic media theory. This project examines the interrelationships between radio, television, newspapers, the ii Internet, and film in the contemporary Rwandan mediascape (which all merge through their relationships with governmental, regulatory, and funding agencies, such as the Rwanda Media High Council - RMHC) to investigate how they endorse national reconciliatory discourse. -

Ed Phelps Logs His 1,000 DTV Station Using Just Himself and His DTV Box. No Autologger Needed

The Magazine for TV and FM DXers October 2020 The Official Publication of the Worldwide TV-FM DX Association Being in the right place at just the right time… WKMJ RF 34 Ed Phelps logs his 1,000th DTV Station using just himself and his DTV Box. No autologger needed. THE VHF-UHF DIGEST The Worldwide TV-FM DX Association Serving the TV, FM, 30-50mhz Utility and Weather Radio DXer since 1968 THE VHF-UHF DIGEST IS THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION DEDICATED TO THE OBSERVATION AND STUDY OF THE PROPAGATION OF LONG DISTANCE TELEVISION AND FM BROADCASTING SIGNALS AT VHF AND UHF. WTFDA IS GOVERNED BY A BOARD OF DIRECTORS: DOUG SMITH, SAUL CHERNOS, KEITH MCGINNIS, JAMES THOMAS AND MIKE BUGAJ Treasurer: Keith McGinnis wtfda.org/info Webmaster: Tim McVey Forum Site Administrator: Chris Cervantez Creative Director: Saul Chernos Editorial Staff: Jeff Kruszka, Keith McGinnis, Fred Nordquist, Nick Langan, Doug Smith, John Zondlo and Mike Bugaj The WTFDA Board of Directors Doug Smith Saul Chernos James Thomas Keith McGinnis Mike Bugaj [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Renewals by mail: Send to WTFDA, P.O. Box 501, Somersville, CT 06072. Check or MO for $10 payable to WTFDA. Renewals by Paypal: Send your dues ($10USD) from the Paypal website to [email protected] or go to https://www.paypal.me/WTFDA and type 10.00 or 20.00 for two years in the box. Our WTFDA.org website webmaster is Tim McVey, [email protected]. -

National Register of Historic Places

Form No. ^0-306 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Independence National Historical Park AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER 313 Walnut Street CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT t Philadelphia __ VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE PA 19106 CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE ^DISTRICT —PUBLIC —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE 2LMUSEUM -BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE X-UNOCCUPIED —^COMMERCIAL 2LPARK .STRUCTURE 2EBOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —XEDUCATIONAL ^.PRIVATE RESIDENCE -SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS -OBJECT —IN PROCESS X-YES: RESTRICTED ^GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: REGIONAL HEADQUABIER REGION STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE PHILA.,PA 19106 VICINITY OF COURTHOUSE, ____________PhiladelphiaREGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. _, . - , - , Ctffv.^ Hall- - STREET & NUMBER n^ MayTftat" CITY. TOWN STATE Philadelphia, PA 19107 TITLE DATE —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY _LOCAL CITY. TOWN CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE ^EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED 2S.ORIGINALSITE _GOOD h^b Jk* SANWJIt's ALTERED _MOVED DATE. —FAIR _UNEXPOSED Description: In June 1948, with passage of Public Law 795, Independence National Historical Park was established to preserve certain historic resources "of outstanding national significance associated with the American Revolution and the founding and growth of the United States." The Park's 39.53 acres of urban property lie in Philadelphia, the fourth largest city in the country. All but .73 acres of the park lie in downtown Phila-* delphia, within or near the Society Hill and Old City Historic Districts (National Register entries as of June 23, 1971, and May 5, 1972, respectively). -

Stations Coverage Map Broadcasters

820 N. Capitol Ave., Lansing, MI 48906 PH: (517) 484-7444 | FAX: (517) 484-5810 Public Education Partnership (PEP) Program Station Lists/Coverage Maps Commercial TV I DMA Call Letters Channel DMA Call Letters Channel Alpena WBKB-DT2 11.2 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WOOD-TV 7 Alpena WBKB-DT3 11.3 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WOTV-TV 20 Alpena WBKB-TV 11 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WXSP-DT2 15.2 Detroit WKBD-TV 14 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WXSP-TV 15 Detroit WWJ-TV 44 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WXMI-TV 19 Detroit WMYD-TV 21 Lansing WLNS-TV 36 Detroit WXYZ-DT2 41.2 Lansing WLAJ-DT2 25.2 Detroit WXYZ-TV 41 Lansing WLAJ-TV 25 Flint-Saginaw-Bay City WJRT-DT2 12.2 Marquette WLUC-DT2 35.2 Flint-Saginaw-Bay City WJRT-DT3 12.3 Marquette WLUC-TV 35 Flint-Saginaw-Bay City WJRT-TV 12 Marquette WBUP-TV 10 Flint-Saginaw-Bay City WBSF-DT2 46.2 Marquette WBKP-TV 5 Flint-Saginaw-Bay City WEYI-TV 30 Traverse City-Cadillac WFQX-TV 32 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WOBC-CA 14 Traverse City-Cadillac WFUP-DT2 45.2 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WOGC-CA 25 Traverse City-Cadillac WFUP-TV 45 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WOHO-CA 33 Traverse City-Cadillac WWTV-DT2 9.2 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WOKZ-CA 50 Traverse City-Cadillac WWTV-TV 9 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WOLP-CA 41 Traverse City-Cadillac WWUP-DT2 10.2 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WOMS-CA 29 Traverse City-Cadillac WWUP-TV 10 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WOOD-DT2 7.2 Traverse City-Cadillac WMNN-LD 14 Commercial TV II DMA Call Letters Channel DMA Call Letters Channel Detroit WJBK-TV 7 Lansing WSYM-TV 38 Detroit WDIV-TV 45 Lansing WILX-TV 10 Detroit WADL-TV 39 Marquette WJMN-TV 48 Flint-Saginaw-Bay -

A Critical Ideological Analysis of Mass Mediated Language

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-2006 Democracy, Hegemony, and Consent: A Critical Ideological Analysis of Mass Mediated Language Michael Alan Glassco Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Glassco, Michael Alan, "Democracy, Hegemony, and Consent: A Critical Ideological Analysis of Mass Mediated Language" (2006). Master's Theses. 4187. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/4187 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEMOCRACY, HEGEMONY, AND CONSENT: A CRITICAL IDEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF MASS MEDIA TED LANGUAGE by Michael Alan Glassco A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College in partial fulfillment'of the requirements for the Degreeof Master of Arts School of Communication WesternMichigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan August 2006 © 2006 Michael Alan Glassco· DEMOCRACY,HEGEMONY, AND CONSENT: A CRITICAL IDEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF MASS MEDIATED LANGUAGE Michael Alan Glassco, M.A. WesternMichigan University, 2006 Accepting and incorporating mediated political discourse into our everyday lives without conscious attention to the language used perpetuates the underlying ideological assumptions of power guiding such discourse. The consequences of such overreaching power are manifestin the public sphere as a hegemonic system in which freemarket capitalism is portrayed as democratic and necessaryto serve the needs of the public. This thesis focusesspecifically on two versions of the Society of ProfessionalJournalist Codes of Ethics 1987 and 1996, thought to influencethe output of news organizations. -

FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, DC 20554

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, DC 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Broadcast Localism ) MB Docket No. 04-233 ) To: The Commission REPLY COMMENTS OF GREATER MEDIA, INC. Greater Media, Inc. (“Greater Media”), through its subsidiaries, is the licensee of the 23 broadcast radio stations listed in attached Exhibit A. Through its attorneys and pursuant to the Commission’s Rules, Greater Media hereby replies to comments filed in response to the Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (“NPRM”) in the above-captioned proceeding. In the NPRM, the Commission solicited comments on proposed regulations that would, inter alia, require the main studio of each broadcast station to be located within the geographic boundaries of the station’s community of license, mandate the propagation of “community advisory boards,” require physical “attendance” of stations during all hours of operation, and reinstate renewal processing “guidelines.” The comments received to date by the Commission indicate an overwhelming lack of public and industry support for these proposals. Still, several commenters applaud them, and urge even more extensive regulation along the same lines.1 In so doing, they echo a primary theme of the NPRM - - that broadcasters are not significantly enough involved in their communities, or sufficiently responsive to community needs. 1 See, e.g., Comments of the Public Interest Public Airwaves Coalition, MB Docket No. 04-233 (April 28, 2008). 262585 Greater Media participated, along with 43 other broadcasting organizations representing more than 600 radio and television stations, in the filing of joint comments in response to the NPRM.2 These joint comments demonstrated how the present proposals would have a far reaching, potentially debilitating impact on the broadcasting industry, while engendering few public benefits. -

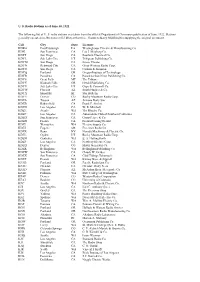

U. S. Radio Stations As of June 30, 1922 the Following List of U. S. Radio

U. S. Radio Stations as of June 30, 1922 The following list of U. S. radio stations was taken from the official Department of Commerce publication of June, 1922. Stations generally operated on 360 meters (833 kHz) at this time. Thanks to Barry Mishkind for supplying the original document. Call City State Licensee KDKA East Pittsburgh PA Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Co. KDN San Francisco CA Leo J. Meyberg Co. KDPT San Diego CA Southern Electrical Co. KDYL Salt Lake City UT Telegram Publishing Co. KDYM San Diego CA Savoy Theater KDYN Redwood City CA Great Western Radio Corp. KDYO San Diego CA Carlson & Simpson KDYQ Portland OR Oregon Institute of Technology KDYR Pasadena CA Pasadena Star-News Publishing Co. KDYS Great Falls MT The Tribune KDYU Klamath Falls OR Herald Publishing Co. KDYV Salt Lake City UT Cope & Cornwell Co. KDYW Phoenix AZ Smith Hughes & Co. KDYX Honolulu HI Star Bulletin KDYY Denver CO Rocky Mountain Radio Corp. KDZA Tucson AZ Arizona Daily Star KDZB Bakersfield CA Frank E. Siefert KDZD Los Angeles CA W. R. Mitchell KDZE Seattle WA The Rhodes Co. KDZF Los Angeles CA Automobile Club of Southern California KDZG San Francisco CA Cyrus Peirce & Co. KDZH Fresno CA Fresno Evening Herald KDZI Wenatchee WA Electric Supply Co. KDZJ Eugene OR Excelsior Radio Co. KDZK Reno NV Nevada Machinery & Electric Co. KDZL Ogden UT Rocky Mountain Radio Corp. KDZM Centralia WA E. A. Hollingworth KDZP Los Angeles CA Newbery Electric Corp. KDZQ Denver CO Motor Generator Co. KDZR Bellingham WA Bellingham Publishing Co. KDZW San Francisco CA Claude W. -

Public Commentary 1-31-17

Stanley Renshon Public Affairs/Commentary-February 2017 I: Commentary Pieces/Op Ed Pieces 33. “Will Mexico Pay for Trump’s Wall?” [on-line debate, John S. Kierman ed], February 16, 2017. https://wallethub.com/blog/will-mexico-pay-for-the- wall/32590/#stanley-renshon 32. “Psychoanalyst to Trump: Grow up and adapt,” USA TODAY, June 23, 2106. http://www.usatoday.com/story/opinion/2016/06/23/trump-psychoanalyst- grow-up-adapt-column/86181242/ 31. “9/11: What would Trump Do?,” Politico Magazine, March 31, 2016. http://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2016/03/donald-trump-2016-terrorist- attack-foreign-policy-213784 30. “You don't know Trump as well as you think,” USA TODAY, March 25, 2106. http://www.usatoday.com/story/opinion/2016/03/25/donald-trump-narcissist- business-leadership-respect-column/82209524/ 29. “Some presidents aspire to be great, more aspire to do well’ essay for “The Big Idea- Diagnosing the Urge to Run for Office,” Politico Magazine, November/December 2015. http://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2015/10/2016-candidates-mental- health-213274?paginate=false 28. “Obama’s Place in History: Great, Good, Average, Mediocre or Poor?,” Washington Post, February 24, 2014. http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/monkey-cage/wp/2014/02/24/obamas- place-in-history-great-good-average-mediocre-or-poor/ 27. President Romney or President Obama: A Tale of Two Ambitions, Montreal Review, October 2012. http://www.themontrealreview.com/2009/President-Romney-or-President- Obama-A-Tale-of-Two-Ambitions.php 26. America Principio, Por Favor, Arizona Daily Star, July 1, 2012. http://azstarnet.com/news/opinion/guest-column-practice-inhibits-forming-full- attachments-to-us/article_10009d68-0fcc-5f4a-8d38-2f5e95a7e138.html 25. -

Media Bureau Call Sign Actions 11/15/2017

PUBLIC NOTICE Federal Communications Commission News Media Information 202-418-0500 445 12th St., S.W. Internet: http://www.fcc.gov Washington, D.C. 20554 TTY: 1-888-835-5322 Report No. 608 Media Bureau Call Sign Actions 11/15/2017 During the period from 10/01/2017 to 10/31/2017 the Commission accepted applications to assign call signs to, or change the call signs of the following broadcast stations. Call Signs Reserved for Pending Sales Applicants Call Sign Service Requested By City State File-Number Former Call Sign KPJK DT RURAL CALIFORNIA BROADCASTING CORPORATION SAN MATEO CA 20171003ACI KCSM-TV KYDQ FM EDUCATIONAL MEDIA FOUNDATION ESCONDIDO CA 20170926AFF KSOQ-FM WKBP FM EDUCATIONAL MEDIA FOUNDATION BENTON PA 20170926AFG WGGI WLJV FM EDUCATIONAL MEDIA FOUNDATION SPOTSYLVANIA VA 20171010ABN WYAU New or Modified Call Signs Row Effective Former Call Call Sign Service Assigned To City State File Number Number Date Sign 1 10/01/2017 KQPV-LP FL ORIENTAL CULTURE CENTER WEST COVINA CA 20131114AWN New 2 10/01/2017 KQSG-LP FL THE EMPEROR'S CIRCLE OF SHEN YUN EL MONTE CA 20131114BOI New 3 10/01/2017 WCHB AM WMUZ RADIO, INC. ROYAL OAK MI WEXL 4 10/01/2017 WMUZ AM WMUZ RADIO, INC. TAYLOR MI WCHB BAL- 5 10/02/2017 KRRD AM OL TIMEY BROADCASTING, LLC FAYETTEVILLE AR KOFC 20170727AFB SALEM MEDIA OF MASSACHUSETTS, 6 10/03/2017 WFIA AM LOUISVILLE KY WJIE LLC DENNIS WALLACE, COURT-APPOINTED 7 10/03/2017 KVMO FM VANDALIA MO KKAC RECEIVER 1 8 10/04/2017 KCCG-LP FL CHURCH OF GOD-GREENVILLE, TX GREENVILLE TX 20131115ASY New BORDERLANDS COMMUNITY MEDIA 9 10/06/2017 KISJ-LP FL BISBEE AZ 20131113BNS New FOUNDATION, INC.