1 Ufuk Onen Bilkent University Bilkent University, Department Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2012 Sundance Film Festival Announces Awards

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contacts: January 28, 2012 Casey De La Rosa 310.360.1981 [email protected] 2012 SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL ANNOUNCES AWARDS The House I Live In, Beasts of the Southern Wild, The Law in These Parts and Violeta Went to Heaven Earn Grand Jury Prizes Audience Favorites Include The Invisible War, The Surrogate, SEARCHING FOR SUGAR MAN and Valley of Saints Sleepwalk With Me Receives Best of NEXT <=> Audience Award Park City, UT — Sundance Institute this evening announced the Jury, Audience, NEXT <=> and other special awards of the 2012 Sundance Film Festival at the Festival‘s Awards Ceremony, hosted by Parker Posey in Park City, Utah. An archived video of the ceremony in its entirety is available at www.sundance.org/live. ―Every year the Sundance Film Festival brings to light exciting new directions and fresh voices in independent film, and this year is no different,‖ said John Cooper, Director of the Sundance Film Festival. ―While these awards further distinguish those that have had the most impact on audiences and our jury, the level of talent showcased across the board at the Festival was really impressive, and all are to be congratulated and thanked for sharing their work with us.‖ Keri Putnam, Executive Director of Sundance Institute, said, ―As we close what was a remarkable 10 days of the 2012 Sundance Film Festival, we look to the year ahead with incredible optimism for the independent film community. As filmmakers continue to push each other to achieve new heights in storytelling we are excited to see what‘s next.‖ The 2012 Sundance Film Festival Awards presented this evening were: The Grand Jury Prize: Documentary was presented by Charles Ferguson to: The House I Live In / U.S.A. -

2017 Highlights

EIGHTH ANNUAL EDITION November 9-16, 2017 “DOC NYC has quickly become one of the city’s grandest film events.” Spans downtown Hailed as Manhattan from “ambitious” IFC Center to 250+ SVA Theatre and films & events “selective but Cinepolis Chelsea eclectic” ARTISTIC DIRECTOR EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Thom Powers programs for the Toronto Raphaela Neihausen & Powers run the weekly International Film Festival and hosts the series Stranger Than Fiction at IFC Center and podcast Pure Nonfiction. host WNYC’s “Documentary of the Week.” DOC NYC has welcomed over 50 sponsors through the years, most of which have returned for 3+ years. ACSIL Discovery Image Nation Abu Dhabi Participant Media Technicolor-Postworks NY Brooklyn Roasting Co. Docurama Impact Partners Peru Ministry of Tribeca Grand Hotel Tourism & Culture Chicago Media Project Essentia Water IndieWire VH1 & Logo Documentary Posteritati Films Chicken & Egg Pictures Goose Island JustFilms/Ford Foundation RADiUS Vulcan Cowan DeBaets Half Pops Abrahams & Sheppard Kickstarter The Screening Room Wheelhouse Creative Heineken CNN Films MTV Stoli The World Channel International City of New York Documentary Association NBCUniversal Archives SundanceNow The Yard Mayor’s Office for Doc Club Media & Entertainment Illy New York Magazine ZICO SVA Owl’s Brew DOCNYC.NET DOCNYCFEST Voted by Movie Maker Magazine as one of the top 5 coolest documentary film festivals in the world! DOC NYC 2016 FEATURED: 12k 200+ likes on Facebook 60k special guests visits DOCNYC.net 125k 92 reached by e-mail Largest premieres Documentary -

Wmc Investigation: 10-Year Analysis of Gender & Oscar

WMC INVESTIGATION: 10-YEAR ANALYSIS OF GENDER & OSCAR NOMINATIONS womensmediacenter.com @womensmediacntr WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER ABOUT THE WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER In 2005, Jane Fonda, Robin Morgan, and Gloria Steinem founded the Women’s Media Center (WMC), a progressive, nonpartisan, nonproft organization endeav- oring to raise the visibility, viability, and decision-making power of women and girls in media and thereby ensuring that their stories get told and their voices are heard. To reach those necessary goals, we strategically use an array of interconnected channels and platforms to transform not only the media landscape but also a cul- ture in which women’s and girls’ voices, stories, experiences, and images are nei- ther suffciently amplifed nor placed on par with the voices, stories, experiences, and images of men and boys. Our strategic tools include monitoring the media; commissioning and conducting research; and undertaking other special initiatives to spotlight gender and racial bias in news coverage, entertainment flm and television, social media, and other key sectors. Our publications include the book “Unspinning the Spin: The Women’s Media Center Guide to Fair and Accurate Language”; “The Women’s Media Center’s Media Guide to Gender Neutral Coverage of Women Candidates + Politicians”; “The Women’s Media Center Media Guide to Covering Reproductive Issues”; “WMC Media Watch: The Gender Gap in Coverage of Reproductive Issues”; “Writing Rape: How U.S. Media Cover Campus Rape and Sexual Assault”; “WMC Investigation: 10-Year Review of Gender & Emmy Nominations”; and the Women’s Media Center’s annual WMC Status of Women in the U.S. -

Media Studies AS Level (AQA)

Media Studies AS Level (AQA) Bridging Booklet AS Units Unit 1 – MEST 1 – Investigating Media (50% of AS Course) Assessment: 2hr examination For this unit you will be studying a variety of Media texts from TV adverts to films to news articles. In addition you will focus on a variety of texts from your case study – documentary and hybrid forms. You will study film and TV documentaries across a variety of ‘Media Platforms’. For example: Broadcasting – the film / TV documentary itself; a TV advert for the film / programme E-media / Internet – a blog about the film / TV programme or the official film / TV/Film website Print – a magazine or newspaper review of the film / TV documentary What AQA says about preparation of your case study topic: ‘candidates should investigate how documentaries are presented across the media, primarily in (audio-visual) broadcasting and cinema platforms, but also the treatment of these in newspapers and magazines, the internet and portable electronic devices. They should study the production and reception of documentary products including the ways in which audiences may consume, participate and respond to documentaries and their coverage.’ The examination for this unit involves answering four questions on two unseen Media texts (moving image or print-based) and then answering one extended question based on your cross-media case study (documentaries). During lessons, you will watch a range of documentary films, some taken from the list below: Amy (2015) The Emperor’s New Clothes (2015) Deep Web (2015) Gascoigne -

Production Notes

Production Notes ABOUT THE FILM Timed to the 50th anniversary of NASA’s celebrated Apollo 11 mission, Apollo 11: First Steps Edition is a thrilling cinematic experience that showcases the real-life moments of humankind’s first steps on the Moon. In this special giant screen edition of Todd Douglas Miller’s (Dinosaur 13) critically acclaimed Apollo 11 documentary, the filmmakers reconstruct the exhilarating final moments of preparation, liftoff, landing, and return of this historic mission—one of humanity’s greatest achievements, and the first to put humans on the Moon. It seems impossible, but this project was possible because of the discovery of a trove of never-before-seen 70mm footage and uncatalogued audio recordings—which allowed the filmmakers to create a 47-minute version of the film tailored exclusively for IMAX® and giant screen theaters in science centers and museums. Apollo 11: First Steps Edition is produced by Statement Pictures in partnership with CNN Films. The film is presented by Land Rover, and distributed by MacGillivray Freeman Films. “The Apollo 11 mission was humanity’s greatest adventure and we’re pleased to be bringing this edition to science centers and museums everywhere,” says director Todd Douglas Miller. “This film was designed to take full advantage of the immersive quality of IMAX and giant screen theaters.” But how did it happen? How did this one-in-a-lifetime batch of footage remain undiscovered for fifty years? Miller explains that as his team was working closely with NASA and the National Archives (NARA) to locate all known Apollo 11 footage, NARA staff members simply discovered reels upon reels of 70mm, large-format Apollo footage. -

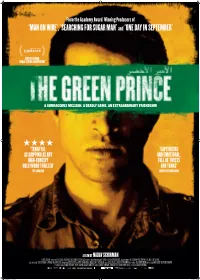

'Man on Wire', 'Searching for Sugar Man

From the Academy Award® Winning Producers of ‘MAN ON WIRE’, ‘SEARCHING FOR SUGAR MAN’ and ‘ONE DAY IN SEPTEMBER’ AUDIENCE AWARD: WORLD CINEMA DOCUMENTARY A COURAGEOUS MISSION. A DEADLY GAME. AN EXTRAORDINARY FRIENDSHIP. ★★★★ ‘TERRIFFIC. ‘CAPTIVATING AS GRIPPING AS ANY AND EMOTIONAL. HIGH-CONCEPT FULL OF TWISTS HOLLYWOOD THRILLER’ AND TURNS’ THE GUARDIAN SCREEN INTERNATIONAL A FILM BY NADAV SCHIRMAN GLOBAL SCREEN PRESENTS AN A-LIST FILMS PASSION PICTURES AND RED BOX FILMS PRODUCTION IN CO-PRODUCTION WITH TELEPOOL AND URZAD PRODUCTIONS IN ASSOCIATION WITH THE DOCUMENTARY COMPANY YES DOCU SKY ATLANTIC BASED ON THE BOOK ‘SON OF HAMAS’ BY MOSAB HASSAN YOUSEF ORIGINAL MUSIC MAX RICHTER DOP HANS FROMM (BVK) GIORA BEJACH RAZ DAGAN EDITORS JOELLE ALEXIS SANJEEV HATHIRAMANI LINE PRODUCER RALF ZIMMERMANN CO-PRODUCERS OMRI UZRAD BRITTA MEYERMANN EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS THOMAS WEYMAR SHERYL CROWN MAGGIE MONTEITH PRODUCERS NADAV SCHIRMAN JOHN BATTSEK SIMON CHINN WRITTEN & DIRECTED BY NADAV SCHIRMAN greenprince_poster_a1_artwork.indd 1 27/01/2014 16:21 A feature documentary from the makers of SEARCHING FOR SUGARMAN, MAN ON WIRE, ONE DAY IN SEPTEMBER and THE CHAMPAGNE SPY A-List Films, Passion Pictures and Red Box Films present THE GREEN PRINCE Written & Directed by Nadav Schirman Produced by Nadav Schirman, John Battsek, Simon Chinn Running Time: 95 mins Press Contact North American Sales World Sales Acme PR Submarine Entertainment Global Screen GmbH Nancy Willen Josh Braun [email protected] 310 963 3433 917 687 3111 +49 89 24412950 [email protected] [email protected] www.globalscreen.de AWARDS & PRESS CLIPPINGS WINNER Audience Award Best World Documentary Sundance International Film Festival 2014 "Terrific.. -

A Film Music Documentary

VULTURE PROUDLY SUPPORTS DOC NYC 2016 AMERICA’s lARGEST DOCUMENTARY FESTIVAL Welcome 4 Staff & Sponsors 8 Galas 12 Special Events 15 Visionaries Tribute 18 Viewfinders 20 Metropolis 24 American Perspectives 29 International Perspectives 33 True Crime 36 DEVOURING TV AND FILM. Science Nonfiction 38 Art & Design 40 @DOCNYCfest ALL DAY. EVERY DAY. Wild Life 43 Modern Family 44 Behind the Scenes 46 Schedule 51 Jock Docs 55 Fight the Power 58 Sonic Cinema 60 Shorts 63 DOC NYC U 68 Docs Redux 71 Short List 73 DOC NYC Pro 83 Film Index 100 Map, Pass and Ticket Information 102 #DOCNYC WELCOME WELCOME LET THE DOCS BEGIN! DOC NYC, America’s Largest Documentary hoarders and obsessives, among other Festival, has returned with another eight days fascinating subjects. of the newest and best nonfiction programming to entertain, illuminate and provoke audiences Building off our world premiere screening of in the greatest city in the world. Our seventh Making A Murderer last year, we’ve introduced edition features more than 250 films and panels, a new t rue CriMe section. Other fresh presented by over 300 filmmakers and thematic offerings include SceC i N e special guests! NONfiCtiON, engaging looks at the worlds of science and technology, and a rt & T HE C ITY OF N EW Y ORK , profiles of artists. These join popular O FFICE OF THE M AYOR This documentary feast takes place at our Design N EW Y ORK, NY 10007 familiar venues in Greenwich Village and returning sections: animal-focused THEl wi D Chelsea. The IFC Center, the SVA Theatre and life, unconventional MODerN faMilY Cinepolis Chelsea host our film screenings, while portraits, cinephile celebrations Behi ND the sCeNes, sports-themed JCO k DO s, November 10, 2016 Cinepolis Chelsea once again does double duty activism-oriented , music as the home of DOC NYC PrO, our panel f iGht the POwer and masterclass series for professional and doc strand Son iC CiNeMa and doc classic aspiring documentary filmmakers. -

Documentary Films Audiences in Europe Findings from the Moving Docs Survey

1 Credit: Moving Docs DOCUMENTARY FILMS AUDIENCES IN EUROPE FINDINGS FROM THE MOVING DOCS SURVEY HUW D JONES July 2020 2 CONTENTS Project team .............................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Foreword ................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Key findings ............................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Introduction .............................................................................................................................................................................. 8 Study method ............................................................................................................................................................................ 9 1. Who watches documentaries? ........................................................................................................................................ 11 2. Where are documentaries viewed? ............................................................................................................................... -

FS 250 DOCUMENTARY FILMMAKING IES Abroad Rome

FS 250 DOCUMENTARY FILMMAKING IES Abroad Rome DESCRIPTION: This Introduction to Documentary Filmmaking will enable students to develop a critical, aesthetic and ethical approach to visual representation. Through selected documentary viewings, readings, class discussions, research projects and the completion of a final documentary project, students will acquire the necessary tools that will help them understand the process needed for making an audiovisual product. The making of a short documentary project on a selected topic will be proposed by the students and approved by the instructor. The documentaries will be based on the new reality in which students will be living and will focus on the differences between cultures, religions, politics, arts, architecture and lifestyles. Students will capture aspects of Italian culture with the advantage of being able to observe it as spectators with a certain amount of detachment. Students will develop the ability to observe, explore, and investigate reality around them. The course fosters a new mode of attentiveness and observation that stimulates and allows students to turn their ideas, intuitions and emotions into visual narratives. Students will learn and discuss all steps involved in the making of documentaries from the conception of the idea to the final film. This process will allow them to develop, in a written form as well, a research project structured in four parts: Theme; Characters; Locations; Story. Students will be trained in the basic technical and creative skills of digital video production and postproduction under the guidance of an experienced filmmaker. They will transform selected research projects into documentaries working in small groups. Students will film and edit also outside class time if necessary. -

Following Is a Listing of Public Relations Firms Who Have Represented Films at Previous Sundance Film Festivals

Following is a listing of public relations firms who have represented films at previous Sundance Film Festivals. This is just a sample of the firms that can help promote your film and is a good guide to start your search for representation. 11th Street Lot 11th Street Lot Marketing & PR offers strategic marketing and publicity services to independent films at every stage of release, from festival premiere to digital distribution, including traditional publicity (film reviews, regional and trade coverage, interviews and features); digital marketing (social media, email marketing, etc); and creative, custom audience-building initiatives. Contact: Lisa Trifone P: 646.926-4012 E: [email protected] www.11thstreetlot.com 42West 42West is a US entertainment public relations and consulting firm. A full service bi-coastal agency, 42West handles film release campaigns, awards campaigns, online marketing and publicity, strategic communications, personal publicity, and integrated promotions and marketing. With a presence at Sundance, Cannes, Toronto, Venice, Tribeca, SXSW, New York and Los Angeles film festivals, 42West plays a key role in supporting the sales of acquisition titles as well as launching a film through a festival publicity campaign. Past Sundance Films the company has represented include Joanna Hogg’s THE SOUVENIR (winner of World Cinema Grand Jury Prize: Dramatic), Lee Cronin’s THE HOLE IN THE GROUND, Paul Dano’s WILDLIFE, Sara Colangelo’s THE KINDERGARTEN TEACHER (winner of Director in U.S. competition), Maggie Bett’s NOVITIATE -

AJH Films Presents, a Passion Pictures Production in Association with KUK Films

AJH Films Presents, A Passion Pictures Production in association with KUK Films Directed by Joseph Martin & Sam Blair Produced by Nicole Stott, Danielle Clark & Alex Holder Running Time: 93 mins WORLD PREMIERE Tribeca Film Festival 2016 Public Screenings Thursday April 14: 6:15pm, Bowtie Cinemas Chelsea 260 West 23rd Street, b/w 7th & Ath Ave (Screen 4) Monday April 18: 6:30pm, Regal Battery Park Stadium 11, 102 North End Ave (Screen 1) Tuesday April 19: 3:30pm, Bowtie Cinemas Chelsea, 260 West 23rd Street, b/w 7th & Ath Ave (Screen 6) Wednesday April 20: 3:15pm, Regal Battery Park Stadium 11, 102 North End Ave (Screen 6) Press Contact: World Sales: Susan Norget Film Promotion The Film Sales Company Susan Norget / Keaton Kail Andrew Herwitz/Jason Ishikawa +212 431 0090 +212 481 5020 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] THE FILM Three years ago, a vehemently anti-Semitic Hungarian far-right politician discovered that he was Jewish. Rejected by his party and unable to uphold the pillars of his previous life, he set out on a remarkable personal journey to confront, learn about and practise his Jewish faith. Keep Quiet charts his astonishing transformation. SYNOPSIS Csanad Szegedi’s story is astonishing. As vice-president of Jobbik, Hungary’s far-right extremist party, Szegedi fervently espoused anti-Semitic rhetoric and was a vocal supporter of the Holocaust denial movement. He was a founder of the Hungarian Guard, a now-banned militia inspired by the Arrow Cross, a pro-Nazi party complicit in the murder of thousands of Jews during the Second World War. -

Oliver Sacks: His Own Life

Photo: Bill Hayes Oliver Sacks: His Own Life A film by Ric Burns Theatrical & Festival Booking Contacts: Nancy Gerstman & Emily Russo, Zeitgeist Films 212-274-1989 • [email protected] • [email protected] Press Contact: FRANK PR Stephanie Davidson | 201-704-1382 [email protected] A ZEITGEIST FILMS RELEASE in association with KINO LORBER Vulcan Productions, Steeplechase Films, American Masters Pictures, Motto Pictures, Passion Pictures, and Tangled Bank Studios present Oliver Sacks: His Own Life Directed by Ric Burns Runtime: 114 Minutes Oliver Sacks: His Own Life Logline Oliver Sacks: His Own Life explores the life and work of the legendary neurologist and storyteller, as he shares intimate details of his battles with drug addiction, homophobia, and a medical establishment that accepted his work only decades after the fact. Sacks was a fearless explorer of unknown mental worlds who helped redefine our understanding of the brain and mind, the diversity of human experience, and our shared humanity. Short Synopsis A month after receiving a fatal diagnosis in January 2015, Oliver Sacks sat down for a series of filmed interviews in his apartment in New York City. For eighty hours, surrounded by family, friends, and notebooks from six decades of thinking and writing about the brain, he talked about his life and work, his abiding sense of wonder at the natural world, and the place of human beings within it. Drawing on these deeply personal reflections, as well as nearly two dozen interviews with close friends, family members, colleagues and patients, and archival material from every point in his life, this film is the story of a beloved doctor and writer who redefined our understanding of the brain and mind.