Ethical Encounters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2012 Sundance Film Festival Announces Awards

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contacts: January 28, 2012 Casey De La Rosa 310.360.1981 [email protected] 2012 SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL ANNOUNCES AWARDS The House I Live In, Beasts of the Southern Wild, The Law in These Parts and Violeta Went to Heaven Earn Grand Jury Prizes Audience Favorites Include The Invisible War, The Surrogate, SEARCHING FOR SUGAR MAN and Valley of Saints Sleepwalk With Me Receives Best of NEXT <=> Audience Award Park City, UT — Sundance Institute this evening announced the Jury, Audience, NEXT <=> and other special awards of the 2012 Sundance Film Festival at the Festival‘s Awards Ceremony, hosted by Parker Posey in Park City, Utah. An archived video of the ceremony in its entirety is available at www.sundance.org/live. ―Every year the Sundance Film Festival brings to light exciting new directions and fresh voices in independent film, and this year is no different,‖ said John Cooper, Director of the Sundance Film Festival. ―While these awards further distinguish those that have had the most impact on audiences and our jury, the level of talent showcased across the board at the Festival was really impressive, and all are to be congratulated and thanked for sharing their work with us.‖ Keri Putnam, Executive Director of Sundance Institute, said, ―As we close what was a remarkable 10 days of the 2012 Sundance Film Festival, we look to the year ahead with incredible optimism for the independent film community. As filmmakers continue to push each other to achieve new heights in storytelling we are excited to see what‘s next.‖ The 2012 Sundance Film Festival Awards presented this evening were: The Grand Jury Prize: Documentary was presented by Charles Ferguson to: The House I Live In / U.S.A. -

Spring 2014 Commencement Program

TE TA UN S E ST TH AT I F E V A O O E L F A DITAT DEUS N A E R R S I O Z T S O A N Z E I A R I T G R Y A 1912 1885 ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY COMMENCEMENT AND CONVOCATION PROGRAM Spring 2014 May 12 - 16, 2014 THE NATIONAL ANTHEM THE STAR SPANGLED BANNER O say can you see, by the dawn’s early light, What so proudly we hailed at the twilight’s last gleaming? Whose broad stripes and bright stars through the perilous fight O’er the ramparts we watched, were so gallantly streaming? And the rockets’ red glare, the bombs bursting in air Gave proof through the night that our flag was still there. O say does that Star-Spangled Banner yet wave O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave? ALMA MATER ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY Where the bold saguaros Raise their arms on high, Praying strength for brave tomorrows From the western sky; Where eternal mountains Kneel at sunset’s gate, Here we hail thee, Alma Mater, Arizona State. —Hopkins-Dresskell MAROON AND GOLD Fight, Devils down the field Fight with your might and don’t ever yield Long may our colors outshine all others Echo from the buttes, Give em’ hell Devils! Cheer, cheer for A-S-U! Fight for the old Maroon For it’s Hail! Hail! The gang’s all here And it’s onward to victory! Students whose names appear in this program have completed degree requirements. -

2017 Highlights

EIGHTH ANNUAL EDITION November 9-16, 2017 “DOC NYC has quickly become one of the city’s grandest film events.” Spans downtown Hailed as Manhattan from “ambitious” IFC Center to 250+ SVA Theatre and films & events “selective but Cinepolis Chelsea eclectic” ARTISTIC DIRECTOR EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Thom Powers programs for the Toronto Raphaela Neihausen & Powers run the weekly International Film Festival and hosts the series Stranger Than Fiction at IFC Center and podcast Pure Nonfiction. host WNYC’s “Documentary of the Week.” DOC NYC has welcomed over 50 sponsors through the years, most of which have returned for 3+ years. ACSIL Discovery Image Nation Abu Dhabi Participant Media Technicolor-Postworks NY Brooklyn Roasting Co. Docurama Impact Partners Peru Ministry of Tribeca Grand Hotel Tourism & Culture Chicago Media Project Essentia Water IndieWire VH1 & Logo Documentary Posteritati Films Chicken & Egg Pictures Goose Island JustFilms/Ford Foundation RADiUS Vulcan Cowan DeBaets Half Pops Abrahams & Sheppard Kickstarter The Screening Room Wheelhouse Creative Heineken CNN Films MTV Stoli The World Channel International City of New York Documentary Association NBCUniversal Archives SundanceNow The Yard Mayor’s Office for Doc Club Media & Entertainment Illy New York Magazine ZICO SVA Owl’s Brew DOCNYC.NET DOCNYCFEST Voted by Movie Maker Magazine as one of the top 5 coolest documentary film festivals in the world! DOC NYC 2016 FEATURED: 12k 200+ likes on Facebook 60k special guests visits DOCNYC.net 125k 92 reached by e-mail Largest premieres Documentary -

Erenews 2020 3 1

ISSN 2531-6214 EREnews© vol. XVIII (2020) 3, 1-45 European Religious Education newsletter July - August - September 2020 Eventi, documenti, ricerche, pubblicazioni sulla gestione del fattore religioso nello spazio pubblico educativo e accademico in Europa ■ Un bollettino digitale trimestrale plurilingue ■ Editor: Flavio Pajer [email protected] EVENTS & DOCUMENTS EUROPEAN COURT OF HUMAN RIGHTS Guide on Art 2: Respect of parental rights, 2 CONSEIL DE L’EUROPE / CDH Une éducation sexuelle complète protège les enfants, 2 EUROPEAN COMMISSION Racial discrimination in education and EU equality law. Report 2020, 3 WCC-PCID Serving a wounded world in interreligious solidarity. A Christian call to reflection, 3 UNICEF-RELIGIONS FOR PEACE Launch of global multireligious Faith-in-Action Covid initiative, 3 OIEC Informe 2020 sobre la educacion catolica mundial en tiempos de crisis, 4 WORLD VALUES SURVEY ASSOCIATION European Values Study. Report 2917-2021, 4 USCIRF Releases new Report about conscientious objection, 4 PEW RESEARCH CENTER Between belief in God and morality: what connection? 4 AGENCY FOR FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS Fighting discrimination on grounds of religion and ethnicity 5 EUROPEAN WERGELAND CENTER 2019 Annual Report, 5 WORLD BANK GROUP / Education Global Practice Simulating the potential impacts of Covid, 5 AMERICAN ACADEMY OF RELIGION AAR Religious Literacy Guidelines, 2020, 6 CENTRE FOR MEDIA MONITORING APPG Religion in the Media inquiry into religious Literacy, 6 NATIONAL CHRONICLES DEUTSCHLAND / NSW Konfessionelle Kooperation in Religionsunterricht, -

Taylor University Echo Chronicle

VOL.6 Upland, Indiana, Dec. 28, 1918 No. 6 PIANO RECITAL. and "Butterfly," by Lavalee, afforded The "Sextet from Lucia," in which All members of Taylor, students opportunity for displaying the pian a splendid left hand technic was and faculty alike, look forward with ist's finger technic. The real poetic shown, is an artistic arrangement pleasure to the various recitals which mood and delicate feeling of "Prim of this well known selection by are given every year by pupils in the rose" by Grieg was, we are sure, Leschetizky, for the left hand alone. music departments. They are always brought to the appreciation of every The beautiful "Symphonie Etude" a source of enjoyment and if we but listener. The program was made which contains so many massive make ourselves attentive and appre varied and interesting by the pleas chord effects is the finale to a group ciative listeners, leave us better quali ing songs rendered by Miss Wertz. of studies by Schumann. This selec fied to know and judge music. In playing the Chaminade "Concert tion formed a fitting closing number First in the series of piano recitals Stuck," Miss Berrett not only dis for the evening's entertainment. this year was the one given Novem played all kinds of finger technic, but The audience was charmed by the ber 16, by Miss Neoma Berrett, stu brought her recital to a most brilliant singing of Miss Kilgore. Her rich dent of Dr. A. Verne Westlake. She climax. mezzo-soprano voice contains a fas was assisted by Miss Lela Wertz, so cinating Creole quality and her num prano, a student of our new and ca HIGH QUALITY bers were well chosen. -

1 Ufuk Onen Bilkent University Bilkent University, Department Of

Ufuk Onen Bilkent University Bilkent University, Department of Communication and Design Bilkent, 06800 Ankara, Turkey [email protected] [email protected] Phone +90-532-421-8769 Ufuk Onen is a sound designer, audio consultant, author, and educator. He works and consults on audio-visual, sound reinforcement, cinema sound installation, and electroacoustic projects. He publishes books, articles, and blog posts. He is a member of the Audio Engineering Society (AES) and served on its Board of Governors (2017-2019). [Department of Communication and Design, Bilkent University, Ankara, Turkey, [email protected]] Article Title: The Voice As a Narrative Element in Documentary Films Article Abstract: Modern documentary filmmakers use fiction-influenced narrative styles that blur the boundaries between fact and fiction, stretching the limits and rules of the genre set by what is referred to as classic or expository documentary. Another major change in the documentary form and narrative style is the inclusion of the filmmaker in the film. As a result of filmmakers starring in their own films, interacting with the subjects, and narrating the story themselves, documentaries have become more personality-driven. In these modern methods, the voices of the narrators and/or the filmmakers carry a significant importance as narrative elements. Taking five music-related documentary films into account—Lot 63, Grave C (Sam Green), Crossing the Bridge: The Sound of Istanbul (Fatih Akin), Metal: A Headbanger's Journey (Sam Dunn, Scot McFadyen, and Jessica Joywise), Decline of Western Civilization Part II: Metal Years (Penelope Spheeris), and Searching for Sugar Man (Malik Bendjelloul)—this paper analyzes how the voices of the narrators and/or the filmmakers are used as narrative elements, and what effects these voices have on the narrative styles and the modes of these documentaries. -

Wmc Investigation: 10-Year Analysis of Gender & Oscar

WMC INVESTIGATION: 10-YEAR ANALYSIS OF GENDER & OSCAR NOMINATIONS womensmediacenter.com @womensmediacntr WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER ABOUT THE WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER In 2005, Jane Fonda, Robin Morgan, and Gloria Steinem founded the Women’s Media Center (WMC), a progressive, nonpartisan, nonproft organization endeav- oring to raise the visibility, viability, and decision-making power of women and girls in media and thereby ensuring that their stories get told and their voices are heard. To reach those necessary goals, we strategically use an array of interconnected channels and platforms to transform not only the media landscape but also a cul- ture in which women’s and girls’ voices, stories, experiences, and images are nei- ther suffciently amplifed nor placed on par with the voices, stories, experiences, and images of men and boys. Our strategic tools include monitoring the media; commissioning and conducting research; and undertaking other special initiatives to spotlight gender and racial bias in news coverage, entertainment flm and television, social media, and other key sectors. Our publications include the book “Unspinning the Spin: The Women’s Media Center Guide to Fair and Accurate Language”; “The Women’s Media Center’s Media Guide to Gender Neutral Coverage of Women Candidates + Politicians”; “The Women’s Media Center Media Guide to Covering Reproductive Issues”; “WMC Media Watch: The Gender Gap in Coverage of Reproductive Issues”; “Writing Rape: How U.S. Media Cover Campus Rape and Sexual Assault”; “WMC Investigation: 10-Year Review of Gender & Emmy Nominations”; and the Women’s Media Center’s annual WMC Status of Women in the U.S. -

Media Studies AS Level (AQA)

Media Studies AS Level (AQA) Bridging Booklet AS Units Unit 1 – MEST 1 – Investigating Media (50% of AS Course) Assessment: 2hr examination For this unit you will be studying a variety of Media texts from TV adverts to films to news articles. In addition you will focus on a variety of texts from your case study – documentary and hybrid forms. You will study film and TV documentaries across a variety of ‘Media Platforms’. For example: Broadcasting – the film / TV documentary itself; a TV advert for the film / programme E-media / Internet – a blog about the film / TV programme or the official film / TV/Film website Print – a magazine or newspaper review of the film / TV documentary What AQA says about preparation of your case study topic: ‘candidates should investigate how documentaries are presented across the media, primarily in (audio-visual) broadcasting and cinema platforms, but also the treatment of these in newspapers and magazines, the internet and portable electronic devices. They should study the production and reception of documentary products including the ways in which audiences may consume, participate and respond to documentaries and their coverage.’ The examination for this unit involves answering four questions on two unseen Media texts (moving image or print-based) and then answering one extended question based on your cross-media case study (documentaries). During lessons, you will watch a range of documentary films, some taken from the list below: Amy (2015) The Emperor’s New Clothes (2015) Deep Web (2015) Gascoigne -

Un'analisi Interpretativa Della Maschilità Nella Televisione

Un’analisi interpretativa della maschilità nella televisione italiana: prospettive pedagogiche INDICE Introduzione 4 PARTE PRIMA 13 Gli stereotipi di genere nel calcio televisivo: l’esempio della maschilità CAPITOLO I 14 Uno sguardo di genere 1.1. La televisione: dispositivo di formazione o cattiva maestra? 15 1.2 Gli stereotipi di genere nella tv italiana 24 1.3 I modelli del maschile tra innovazione e tradizione 32 1.4 L’ostentazione del corpo nell’era della spettacolarizzazione: il calcio moderno 42 1.5 Relazioni di potere e discriminazione simbolica: calciatori e veline 49 CAPITOLO 2 58 Il corpo maschile come modello ideologico 2.1 L’esibizione narcisistica del leader: Josè Mourinho 63 2.2 Fenomeno italiano o globale? La retorica virilistica nell’Inter dei tre titoli 70 2.3 Il calcio e la dialettica valori-denaro nelle immagini mediatiche 82 2.4 Guerra e religione nella Spagna del Barcellona di Guardiola 91 PARTE SECONDA 100 Prospettive pedagogiche: la ricerca azione partecipativa CAPITOLO 3 101 Genere e formazione: la pedagogia della differenza 3.1 La maschilità nel calcio in tv e gli adolescenti 102 3.2 La pedagogia della differenza tra feminist media studies e men’s studies 112 3.3 L’importanza della scuola come ambiente riflessivo 124 3.4 Per un uso “ecologico” della tv: decostruire gli stereotipi di genere tramite il metodo narrativo nella Ricerca Qualitativa 134 CAPITOLO 4 146 La ricerca-azione 4.1 Metodologia dell’indagine qualitativa: la ricerca azione partecipativa 147 4.2 La ricerca sul campo: le interviste 157 4.3. Le interviste: il brainstorming 163 4.3 a La pubblicità: maschile e femminile tra caos e ordine 170 4.3 b L’importante è buttarla dentro? 175 2 4.3 c Uomini e donne nell’era della videocrazia 178 4.3 d Il corpo delle donne tra ragazze-immagine e showgirl 182 4.3 e La differenza dei sessi nello sport…e nel calcio 195 4.3 f La maschilità tra tradizione e innovazione: Josè Mourinho 201 4.4 Gli elaborati scritti 207 4.5 L’analisi T-Lab 228 CONCLUSIONI GENERALI 255 BIBLIOGRAFIA 260 3 Introduzione Questo lavoro di Tesi si compone di due parti. -

Production Notes

Production Notes ABOUT THE FILM Timed to the 50th anniversary of NASA’s celebrated Apollo 11 mission, Apollo 11: First Steps Edition is a thrilling cinematic experience that showcases the real-life moments of humankind’s first steps on the Moon. In this special giant screen edition of Todd Douglas Miller’s (Dinosaur 13) critically acclaimed Apollo 11 documentary, the filmmakers reconstruct the exhilarating final moments of preparation, liftoff, landing, and return of this historic mission—one of humanity’s greatest achievements, and the first to put humans on the Moon. It seems impossible, but this project was possible because of the discovery of a trove of never-before-seen 70mm footage and uncatalogued audio recordings—which allowed the filmmakers to create a 47-minute version of the film tailored exclusively for IMAX® and giant screen theaters in science centers and museums. Apollo 11: First Steps Edition is produced by Statement Pictures in partnership with CNN Films. The film is presented by Land Rover, and distributed by MacGillivray Freeman Films. “The Apollo 11 mission was humanity’s greatest adventure and we’re pleased to be bringing this edition to science centers and museums everywhere,” says director Todd Douglas Miller. “This film was designed to take full advantage of the immersive quality of IMAX and giant screen theaters.” But how did it happen? How did this one-in-a-lifetime batch of footage remain undiscovered for fifty years? Miller explains that as his team was working closely with NASA and the National Archives (NARA) to locate all known Apollo 11 footage, NARA staff members simply discovered reels upon reels of 70mm, large-format Apollo footage. -

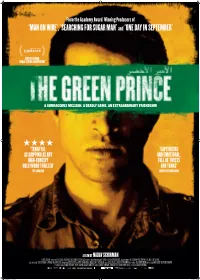

'Man on Wire', 'Searching for Sugar Man

From the Academy Award® Winning Producers of ‘MAN ON WIRE’, ‘SEARCHING FOR SUGAR MAN’ and ‘ONE DAY IN SEPTEMBER’ AUDIENCE AWARD: WORLD CINEMA DOCUMENTARY A COURAGEOUS MISSION. A DEADLY GAME. AN EXTRAORDINARY FRIENDSHIP. ★★★★ ‘TERRIFFIC. ‘CAPTIVATING AS GRIPPING AS ANY AND EMOTIONAL. HIGH-CONCEPT FULL OF TWISTS HOLLYWOOD THRILLER’ AND TURNS’ THE GUARDIAN SCREEN INTERNATIONAL A FILM BY NADAV SCHIRMAN GLOBAL SCREEN PRESENTS AN A-LIST FILMS PASSION PICTURES AND RED BOX FILMS PRODUCTION IN CO-PRODUCTION WITH TELEPOOL AND URZAD PRODUCTIONS IN ASSOCIATION WITH THE DOCUMENTARY COMPANY YES DOCU SKY ATLANTIC BASED ON THE BOOK ‘SON OF HAMAS’ BY MOSAB HASSAN YOUSEF ORIGINAL MUSIC MAX RICHTER DOP HANS FROMM (BVK) GIORA BEJACH RAZ DAGAN EDITORS JOELLE ALEXIS SANJEEV HATHIRAMANI LINE PRODUCER RALF ZIMMERMANN CO-PRODUCERS OMRI UZRAD BRITTA MEYERMANN EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS THOMAS WEYMAR SHERYL CROWN MAGGIE MONTEITH PRODUCERS NADAV SCHIRMAN JOHN BATTSEK SIMON CHINN WRITTEN & DIRECTED BY NADAV SCHIRMAN greenprince_poster_a1_artwork.indd 1 27/01/2014 16:21 A feature documentary from the makers of SEARCHING FOR SUGARMAN, MAN ON WIRE, ONE DAY IN SEPTEMBER and THE CHAMPAGNE SPY A-List Films, Passion Pictures and Red Box Films present THE GREEN PRINCE Written & Directed by Nadav Schirman Produced by Nadav Schirman, John Battsek, Simon Chinn Running Time: 95 mins Press Contact North American Sales World Sales Acme PR Submarine Entertainment Global Screen GmbH Nancy Willen Josh Braun [email protected] 310 963 3433 917 687 3111 +49 89 24412950 [email protected] [email protected] www.globalscreen.de AWARDS & PRESS CLIPPINGS WINNER Audience Award Best World Documentary Sundance International Film Festival 2014 "Terrific.. -

CLASSIFIED ADS Home?" Starring Laurel & Hardy

set about the rebuilding of the small Coates presented the program on the behind the console. They seemed to organ. It must be said at this point organ and piano. set the mood for the meeting, and I'm that to this writer, no group ever The end of the year in St. Louis told, were the handiwork of Mrs. Jureit. showed such great spirit in the face of signals a "New Beginning" for us with The featured artist this Sunday disappointment or such "espirit de the hope of '72 seeing the small organ afternoon was Pete Dumser, and artist corp" in banding together to start playing and a new home for its larger he is, for he wove a melodic medley of another project. We all looked for sister. At any rate, watch our smoke traditional and pop Christmas music, ward eagerly to the Affton project and this year and a happy and prosperous punctuated by familiar standards. His when it didn't pan out everyone just and productive new year to us all ... program was well received. The "early picked himself up (as the song says) "Ten-Four". bird" feature was the early birds them and went back to work with new JOHN FERGUSON selves. Perhaps Lee Taylor coaxed sights. music from the big instrument which We don't feel at liberty yet to dis encouraged the more timid souls to close the location of the little Wur SOUTH FLORIDA try their hands, and the "open con litzer at this printing, but work on the Bouquets to Mr.