The Comic Book Is Dead, Long Live the Comic Book V3.0 by Tony C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Magazines V17N9.Qxd

Feb COF C1:Customer 1/6/2012 2:54 PM Page 1 ORDERS DUE th 18FEB 2012 FEB E COMIC H T SHOP’S CATALOG 02 FEBRUARY COF Apparel Shirt Ad:Layout 1 1/11/2012 1:45 PM Page 1 DC HEROES: “SUPER POWERS” Available only TURQUOISE T-SHIRT from your local comic shop! PREORDER NOW! SPIDER-MAN: DEADPOOL: “POOL SHOT” PLASTIC MAN: “DOUBLE VISION” BLACK T-SHIRT “ALL TIED UP” BURGUNDY T-SHIRT PREORDER NOW! CHARCOAL T-SHIRT PREORDER NOW! PREORDER NOW! COF Gem Page February:gem page v18n1.qxd 1/11/2012 1:29 PM Page 1 STAR WARS: MASS EFFECT: BLOOD TIES— HOMEWORLDS #1 BOBA FETT IS DEAD #1 DARK HORSE COMICS (OF 4) DARK HORSE COMICS WONDER WOMAN #8 DC COMICS RICHARD STARK’S PARKER: STIEG LARSSON’S THE SCORE HC THE GIRL WITH THE DRAGON IDW PUBLISHING TATTOO SPECIAL #1 DC COMICS / VERTIGO SECRET #1 IMAGE COMICS AMERICA’S GOT POWERS #1 (OF 6) AVENGERS VS. X-MEN: IMAGE COMICS VS. #1 (OF 6) MARVEL COMICS COF FI page:FI 1/12/2012 10:00 AM Page 1 FEATURED ITEMS COMICS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Girl Genius Volume 11: Agatha Heterodyne and the Hammerless Bell TP/HC G AIRSHIP ENTERTAINMENT Strawberry Shortcake Volume 1: Berry Fun TP G APE ENTERTAINMENT Bart Simpson‘s Pal, Milhouse #1 G BONGO COMICS Fanboys Vs. Zombies #1 G BOOM! STUDIOS 1 1 Roger Langridge‘s Snarked! Volume 1 TP G BOOM! STUDIOS/KABOOM! Lady Death Origins: Cursed #1 G BOUNDLESS COMICS The Shadow #1 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT The Shadow: Blood & Judgment TP G D. -

Cartoon Network: Super Secret Crisis War!

SAMURAI JACK created by GENNDY TARTAKOVSKY BEN 10 created by MAN OF ACTION STUDIOS DEXTER'S LABORATORY created by GENNDY TARTAKOVSKY THE POWERPUFF GIRLS created by CRAIG McCRACKEN ED, EDD N' EDDY created by DANNY ANTONUCCI Special thanks to Laurie Halal-Ono, Rick Blanco, Jeff Parker and Marisa Marionakis of Cartoon Network. Ted Adams, CEO & Publisher Facebook: facebook.com/idwpublishing Greg Goldstein, President & COO Robbie Robbins, EVP/Sr. Graphic Artist Twitter: @idwpublishing Chris Ryall, Chief Creative Officer/Editor-in-Chief YouTube: youtube.com/idwpublishing Matthew Ruzicka, CPA, Chief Financial Officer Alan Payne, VP of Sales Instagram: instagram.com/idwpublishing Dirk Wood, VP of Marketing deviantART: idwpublishing.deviantart.com www.IDWPUBLISHING.com Lorelei Bunjes, VP of Digital Services IDW founded by Ted Adams, Alex Garner, Kris Oprisko, and Robbie Robbins Jeff Webber, VP of Digital Publishing & Business Development Pinterest: pinterest.com/idwpublishing/idw-staff-faves SUPER SECRET CRISIS WAR! #1. JUNE 2014. FIRST PRINTING.™ and © Cartoon Network (s14). IDW Publishing, a division of Idea and Design Works, LLC. Editorial offices: 5080 Santa Fe St., San Diego, CA 92109. The IDW logo is registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. Any similarities to persons living or dead are purely coincidental. With the exception of artwork used for review purposes, none of the contents of this publication may be reprinted without the permission of Idea and Design Works, LLC. Printed in Korea. IDW Publishing does not read or accept unsolicited submissions of ideas, stories, or artwork. Louise Derek Charm Simonson (artist) lives in New (writer) has edited York City, where and written comics he works as an since the dawn illustrator creating of time. -

Captain America

The Star-spangled Avenger Adapted from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Captain America first appeared in Captain America Comics #1 (Cover dated March 1941), from Marvel Comics' 1940s predecessor, Timely Comics, and was created by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby. For nearly all of the character's publication history, Captain America was the alter ego of Steve Rogers , a frail young man who was enhanced to the peak of human perfection by an experimental serum in order to aid the United States war effort. Captain America wears a costume that bears an American flag motif, and is armed with an indestructible shield that can be thrown as a weapon. An intentionally patriotic creation who was often depicted fighting the Axis powers. Captain America was Timely Comics' most popular character during the wartime period. After the war ended, the character's popularity waned and he disappeared by the 1950s aside from an ill-fated revival in 1953. Captain America was reintroduced during the Silver Age of comics when he was revived from suspended animation by the superhero team the Avengers in The Avengers #4 (March 1964). Since then, Captain America has often led the team, as well as starring in his own series. Captain America was the first Marvel Comics character adapted into another medium with the release of the 1944 movie serial Captain America . Since then, the character has been featured in several other films and television series, including Chris Evans in 2011’s Captain America and The Avengers in 2012. The creation of Captain America In 1940, writer Joe Simon conceived the idea for Captain America and made a sketch of the character in costume. -

Saturday Auction Preliminary Catalog

LOT TITLE DESCRIPTION Collection of Letters from Henry Steeger — founder of 400 Popular Publications — to Nick Carr Proceeds to Wooda “Nick” Carr 1/28/28, 2/4/28, 2/18/28, 2/25/28, 3/10/28, 4/7/28, 4/21/28, 401 12 issues WESTERN STORY MAGAZINE (1928) 5/12/28, 5/19/28, 6/23/28, 7/14/28, 7/28/28 8/4/28, 8/18/28, 8/25/28, 9/8/28, 9/15/28, 9/22/28, 11/24/28, 402 10 issues WESTERN STORY MAGAZINE (1928-1929) 12/22/28, 1/5/29, 1/26/29 2/9/29, 3/9/29, 7/27/29, 8/3/29, 8/10/29, 8/17/29, 8/24/29, 403 12 issues WESTERN STORY MAGAZINE (1929) 9/7/29, 9/14/29, 9/21/29, 9/28/29, 11/16/29 1/11/30, 2/8/30, 3/22/30, 4/5/30, 5/17/30, 7/19/30, 8/2/30, 404 10 issues WESTERN STORY MAGAZINE (1930) 8/9/30, 11/8/30, 12/27/30 5/9/31, 5/23/31, 6/13/31, 7/18/31, 4/16/32, 8/13/32, 8/27/32, 405 10 issues WESTERN STORY MAGAZINE (1931-1932) 9/3/32, 10/22/32, 11/19/32 5/13/33, 5/27/33, 8/19/33, 9/9/33, 9/23/33, 11/25/33, 1/13/34, 406 10 issues WESTERN STORY MAGAZINE (1933-1934) 2/10/34, 2/17/34, 3/17/34 3/31/34, 5/12/34, 5/26/34, 12/15/34, 1/19/35, 1/26/35, 2/2/35, 407 10 issues WESTERN STORY MAGAZINE (1934-1935) 2/9/35, 2/23/35, 3/16/35 3/10/35, 4/6/35, 4/20/35, 5/4/35, 5/11/35, 5/18/35, 5/25/35, 408 10 issues WESTERN STORY MAGAZINE (1935) 6/1/35, 6/8/35, 6/15/35 2/5/44, 10/44, 2/45, 8/45, 10/45, 1/46, 2/46, 3/46, 4/46, 5/46, 409 15 issues WESTERN STORY MAGAZINE (digest size) 6/46, 7/46, 8/46, 9/46, 10/46 1/47, 3/47, 4/47, 9/47, 2/48, 5/48, 1948 annual, 3/49, 5/49, 8 & 410 10 issues WESTERN STORY MAGAZINE (digest size) 9/49 CONAN THE CONQUEROR & THE SWORD OF 411 RHIANNON -

Graphic Novels for Children and Teens

J/YA Graphic Novel Titles The 9/11 Report: A Graphic Adaptation Sid Jacobson Hill & Wang Gr. 9+ Age of Bronze, Volume 1: A Thousand Ships Eric Shanower Image Comics Gr. 9+ The Amazing “True” Story of a Teenage Single Mom Katherine Arnoldi Hyperion Gr. 9+ American Born Chinese Gene Yang First Second Gr. 7+ American Splendor Harvey Pekar Vertigo Gr. 10+ Amy Unbounded: Belondweg Blossoming Rachel Hartman Pug House Press Gr. 3+ The Arrival Shaun Tan A.A. Levine Gr. 6+ Astonishing X-Men Joss Whedon Marvel Gr. 9+ Astro City: Life in the Big City Kurt Busiek DC Comics Gr. 10+ Babymouse Holm, Jennifer Random House Children’s Gr. 1-5 Baby-Sitter’s Club Graphix (nos. 1-4) Ann M. Martin & Raina Telgemeier Scholastic Gr. 3-7 Barefoot Gen, Volume 1: A Cartoon Story of Hiroshima Keiji Nakazawa Last Gasp Gr. 9+ Beowulf (graphic adaptation of epic poem) Gareth Hinds Candlewick Press Gr. 7+ Berlin: City of Stones Berlin: City of Smoke Jason Lutes Drawn & Quarterly Gr. 9+ Blankets Craig Thompson Top Shelf Gr. 10+ Bluesman (vols. 1, 2, & 3) Rob Vollmar NBM Publishing Gr. 10+ Bone Jeff Smith Cartoon Books Gr. 3+ Breaking Up: a Fashion High graphic novel Aimee Friedman Graphix Gr. 5+ Buffy the Vampire Slayer (Season 8) Joss Whedon Dark Horse Gr. 7+ Castle Waiting Linda Medley Fantagraphics Gr. 5+ Chiggers Hope Larson Aladdin Mix Gr. 5-9 Cirque du Freak: the Manga Darren Shan Yen Press Gr. 7+ City of Light, City of Dark: A Comic Book Novel Avi Orchard Books Gr. -

We Spoke Out: Comic Books and the Holocaust

W E SPOKE OUT COMIC BOOKS W E SPOKE OUT COMIC BOOKS AND THE HOLOCAUST AND NEAL ADAMS RAFAEL MEDOFF CRAIG YOE INTRODUCTION AND THE HOLOCAUST AFTERWORD BY STAN LEE NEAL ADAMS MEDOFF RAFAEL CRAIG YOE LEE STAN “RIVETING!” —Prof. Walter Reich, Former Director, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Long before the Holocaust was widely taught in schools or dramatized in films such asSchindler’s List, America’s youth was learning about the Nazi genocide from Batman, X-Men, and Captain America. Join iconic artist Neal Adams, the legend- ary Stan Lee, Holocaust scholar Dr. Rafael Medoff, and Eisner-winning comics historian Craig Yoe as they take you on an extraordinary journey in We Spoke Out: Comic Books and the Holocaust. We Spoke Out showcases classic comic book stories about the Holocaust and includes commentaries by some of their pres- tigious creators. Writers whose work is featured include Chris Claremont, Archie Goodwin, Al Feldstein, Robert Kanigher, Harvey Kurtzman, and Roy Thomas. Along with Neal Adams (who also drew the cover of this remarkable volume), artists in- clude Gene Colan, Jack Davis, Carmine Infantino, Gil Kane, Bernie Krigstein, Frank Miller, John Severin, and Wally Wood. In We Spoke Out, you’ll see how these amazing comics creators helped introduce an entire generation to a compelling and important subject—a topic as relevant today as ever. ® Visit ISBN: 978-1-63140-888-5 YoeBooks.com idwpublishing.com $49.99 US/ $65.99 CAN ® ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors are grateful to friends and colleagues who assisted with various aspects of this project: Kris Stone and Peter Stone, of Continuity Studios; Gregory Pan, of Marvel Comics; Thomas Wood, Jay Kogan, and Mandy Noack-Barr, of DC Comics; Dan Braun, of New Comic Company (Warren Publications); Corey Mifsud, Cathy Gaines-Mifsud, and Dorothy Crouch of EC Comics; Robert Carter, Jon Gotthold, Michelle Nolan, Thomas Martin, Steve Fears, Rich Arndt, Kevin Reddy, Steve Bergson, and Jeff Reid, who provided information or scans; Jon B. -

SILVER AGE SENTINELS (D20)

Talking Up Our Products With the weekly influx of new roleplaying titles, it’s almost impossible to keep track of every product in every RPG line in the adventure games industry. To help you organize our titles and to aid customers in finding information about their favorite products, we’ve designed a set of point-of-purchase dividers. These hard-plastic cards are much like the category dividers often used in music stores, but they’re specially designed as a marketing tool for hobby stores. Each card features the name of one of our RPG lines printed prominently at the top, and goes on to give basic information on the mechanics and setting of the game, special features that distinguish it from other RPGs, and the most popular and useful supplements available. The dividers promote the sale of backlist items as well as new products, since they help customers identify the titles they need most and remind buyers to keep them in stock. Our dividers can be placed in many ways. These are just a few of the ideas we’ve come up with: •A divider can be placed inside the front cover or behind the newest release in a line if the book is displayed full-face on a tilted backboard or book prop. Since the cards 1 are 11 /2 inches tall, the line’s title will be visible within or in back of the book. When a customer picks the RPG up to page through it, the informational text is uncovered. The card also works as a restocking reminder when the book sells. -

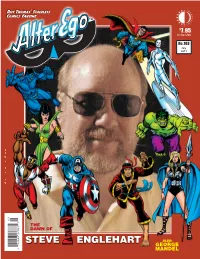

Englehart Steve

AE103Cover FINAL_AE49 Trial Cover.qxd 6/22/11 4:48 PM Page 1 BOOKS FROM TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING Roy Thomas’ Stainless Comics Fanzine $7.95 In the USA No.103 July 2011 STAN LEE UNIVERSE CARMINE INFANTINO SAL BUSCEMA MATT BAKER The ultimate repository of interviews with and PENCILER, PUBLISHER, PROVOCATEUR COMICS’ FAST & FURIOUS ARTIST THE ART OF GLAMOUR mementos about Marvel Comics’ fearless leader! Shines a light on the life and career of the artistic Explores the life and career of one of Marvel Comics’ Biography of the talented master of 1940s “Good (176-page trade paperback) $26.95 and publishing visionary of DC Comics! most recognizable and dependable artists! Girl” art, complete with color story reprints! (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 (224-page trade paperback) $26.95 (176-page trade paperback with COLOR) $26.95 (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 QUALITY COMPANION BATCAVE COMPANION EXTRAORDINARY WORKS IMAGE COMICS The first dedicated book about the Golden Age Unlocks the secrets of Batman’s Silver and Bronze OF ALAN MOORE THE ROAD TO INDEPENDENCE publisher that spawned the modern-day “Freedom Ages, following the Dark Knight’s progression from Definitive biography of the Watchmen writer, in a An unprecedented look at the company that sold Fighters”, Plastic Man, and the Blackhawks! 1960s camp to 1970s creature of the night! new, expanded edition! comics in the millions, and their celebrity artists! (256-page trade paperback with COLOR) $31.95 (240-page trade paperback) $26.95 (240-page trade paperback) $29.95 (280-page trade -

Sloane Drayson Knigge Comic Inventory (Without

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Number Donor Box # 1,000,000 DC One Million 80-Page Giant DC NA NA 1999 NA Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 A Moment of Silence Marvel Bill Jemas Mark Bagley 2002 1 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alex Ross Millennium Edition Wizard Various Various 1999 NA Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Open Space Marvel Comics Lawrence Watt-Evans Alex Ross 1999 0 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alf Marvel Comics Michael Gallagher Dave Manak 1990 33 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 1999 1 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 1999 2 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 1999 3 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 1999 4 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 2000 5 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 2000 6 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Aphrodite IX Top Cow Productions David Wohl and Dave Finch Dave Finch 2000 0 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Veronica Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 600 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Veronica Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 601 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Veronica Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 602 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Betty Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 603 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Betty Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 -

Improving Healthy Food Retail for Coloradans – March 2019

Improving Healthy Food Retail for Coloradans – March 2019 Summary The goal of the paper is to advise state government and other partner organizations on ways to enhance statewide accessibility to healthy foods by 1) increasing the number of food vendors that accept Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) benefits and 2) maximizing opportunities for WIC- and SNAP-authorized food vendors to provide and influence purchases of healthier foods as identified in the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Such efforts will improve food access for those on food assistance and increase access to nutritious food for the entire community. Farmers, retailers, and local economies will benefit from the additional dollars spent by those receiving nutrition assistance. Contents I. Introduction & Overview 3 II. Overview of Federal Food Assistance Programs in Colorado 4 Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) 4 Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program – Education (SNAP-Ed) 7 Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children 7 III. Retail Requirements 8 Requirements for SNAP-Authorized Food Vendors 8 Requirements for WIC-Authorized Food Vendors 10 IV. Food Vendors that Accept Federal Benefits 10 Food Vendor Types That Can Accept Benefits 10 Authorized Food Vendors in Colorado 11 Implications for the Expansion of WIC- and SNAP-Authorized Food Vendors 12 V. Current Conditions and Assets 13 Healthy Corner Stores 13 Healthy Food Incentives 13 -

Matt Groening and Lynda Barry Love, Hate & Comics—The Friendship That Would Not Die

H O S n o t p U e c n e d u r P Saturday, October 7, 201 7, 8pm Zellerbach Hall Matt Groening and Lynda Barry Love, Hate & Comics—The Friendship That Would Not Die Cal Performances’ 2017 –18 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. ABOUT THE ARTISTS Matt Groening , creator and executive producer Simpsons , Futurama, and Life in Hell . Groening of the Emmy Award-winning series The Simp - has launched The Simpsons Store app and the sons , made television history by bringing Futuramaworld app; both feature online comics animation back to prime time and creating an and books. immortal nuclear family. The Simpsons is now The multitude of awards bestowed on Matt the longest-running scripted series in television Groening’s creations include Emmys, Annies, history and was voted “Best Show of the 20th the prestigious Peabody Award, and the Rueben Century” by Time Magazine. Award for Outstanding Cartoonist of the Year, Groening also served as producer and writer the highest honor presented by the National during the four-year creation process of the hit Cartoonists Society. feature film The Simpsons Movie , released in Netflix has announced Groening’s new series, 2007. In 2009 a series of Simpsons US postage Disenchantment . stamps personally designed by Groening was released nationwide. Currently, the television se - Lynda Barry has worked as a painter, cartoon - ries is celebrating its 30th anniversary and is in ist, writer, illustrator, playwright, editor, com - production on the 30th season, where Groening mentator, and teacher, and found they are very continues to serve as executive producer. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Afrodisiac by Jim Rugg Afrodisiac by Jim Rugg

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Afrodisiac by Jim Rugg Afrodisiac by Jim Rugg. January 7, 2010 at 3:38 pm By: Dustin Harbin. Shazam! Coming up on February 7 , just one short month away, Heroes Aren’t Hard To Find will be hosting Afrodisiac ‘s Jim Rugg ! Jim is also the co-writer of the book, along with Brian Maruca ; the two first created Afrodisiac in the pages of their Street Angel series. Jim has also been the artist on several graphic novels with other collaborators, including The Plain Janes and Janes In Love with writer Cecil Castellucci . But enough about all that. AFRODISIAC . This is a pretty hotly anticipated book–Jim has turned into a sort of cartoonist’s cartoonist over the last few years, and he’s definitely showing off in Afrodisiac, switching up styles like Kool & The Gang switches up the rhythm. That was a 70’s funk reference, dig it? The book is chock full of them, and much better ones too– Afrodisiac is (if I have this right) a kind of amalgamation of 70’s-era comic books, blaxploitation films, and sexy times. All filtered through the minds of a couple of dudes from Pennsylvania who grew up on all that stuff. Anyway. Jim will be appearing in our store Sunday, February 7, from 3-6pm , for a signing and a discussion of the book. He’ll be joined by AdHouse Books publisher Chris Pitzer , there mainly for security in case any of you ladies try to swarm Jim or anything. Our Heroes Discussion Group leader Andy Mansell will also be on hand–those of you who have attended any of the Discussion Groups know Andy will close-read a book like no one else, so expect some high quality questions–no extra charge! And there’ll be plenty for Andy to talk about– Afrodisiac is filled with more double entendres than.