Digital Comics: Panel Structure in a Digital Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Captain America

The Star-spangled Avenger Adapted from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Captain America first appeared in Captain America Comics #1 (Cover dated March 1941), from Marvel Comics' 1940s predecessor, Timely Comics, and was created by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby. For nearly all of the character's publication history, Captain America was the alter ego of Steve Rogers , a frail young man who was enhanced to the peak of human perfection by an experimental serum in order to aid the United States war effort. Captain America wears a costume that bears an American flag motif, and is armed with an indestructible shield that can be thrown as a weapon. An intentionally patriotic creation who was often depicted fighting the Axis powers. Captain America was Timely Comics' most popular character during the wartime period. After the war ended, the character's popularity waned and he disappeared by the 1950s aside from an ill-fated revival in 1953. Captain America was reintroduced during the Silver Age of comics when he was revived from suspended animation by the superhero team the Avengers in The Avengers #4 (March 1964). Since then, Captain America has often led the team, as well as starring in his own series. Captain America was the first Marvel Comics character adapted into another medium with the release of the 1944 movie serial Captain America . Since then, the character has been featured in several other films and television series, including Chris Evans in 2011’s Captain America and The Avengers in 2012. The creation of Captain America In 1940, writer Joe Simon conceived the idea for Captain America and made a sketch of the character in costume. -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

The New Age, New Face of Graphic Novels Graphic of Face New Age, New the FOCUS: SPECIAL

Childrenthe journal of the Association for Library Service to Children &LibrariesVolume 9 Number 1 Spring 2011 ISSN 1542-9806 SPECIAL FOCUS: The New Age, New Face of Graphic Novels Great Collaborations • Bechtel Fellow Studies ABCs PERMIT NO. 4 NO. PERMIT Change Service Requested Service Change HANOVER, PA HANOVER, Chicago, Illinois 60611 Illinois Chicago, PAID 50 East Huron Street Huron East 50 U.S. POSTAGE POSTAGE U.S. Association for Library Service to Children to Service Library for Association NONPROFIT ORG. NONPROFIT Table Contents● ofVolume 9, Number 1 Spring 2011 Notes 28 “A” is for Alligator Or How a Bechtel Fellow Learns the 2 Editor’s Note Alphabet Sharon Verbeten Joyce Laiosa 2 The Dog-Eared Page 35 My Year with Geisel James K. Irwin features 3 Special Focus: Graphic Novels 37 When it Rains Stuffed Animals Good Comics for Kids A Lesson in Handling the Unexpected Deanna Romriell Collecting Graphic Novels for Young Readers Eva Volin 41 A Viable Venue 10 When a “Graphic” Won the Geisel The Public Library as a Haven for Youth Development A Critical Look at Benny and Penny in the Kenneth R. Jones and Terence J. Delahanty Big No-No! Susan Veltfort 45 From Research to a Thrill An Interview with Margaret Peterson Haddix 12 Visual Literacy Timothy Capehart Exploring This Magic Portal Françoise Mouly 48 Summer Reading on Steroids ALSC/BWI Grant Winner Hosts 15 Special Collections Column Superhero SRP A Comic Book Surprise Faith Brautigam The Library of Congress and Graphic Novels Janet Weber Departments 17 Making Learning the Library Fun One Library’s Kidz Connect Program 11 Call for Referees Monica Sands 27 Author Guidelines 53 ALSC News 20 Beyond Storytime 63 Index to Advertisers Children’s Librarians Collaborating 64 The Last Word in Communities Sue Rokos Tess Prendergast Cover: Alaina Gerbers of Green Bay, Wis. -

Mcwilliams Ku 0099D 16650

‘Yes, But What Have You Done for Me Lately?’: Intersections of Intellectual Property, Work-for-Hire, and The Struggle of the Creative Precariat in the American Comic Book Industry © 2019 By Ora Charles McWilliams Submitted to the graduate degree program in American Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Co-Chair: Ben Chappell Co-Chair: Elizabeth Esch Henry Bial Germaine Halegoua Joo Ok Kim Date Defended: 10 May, 2019 ii The dissertation committee for Ora Charles McWilliams certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: ‘Yes, But What Have You Done for Me Lately?’: Intersections of Intellectual Property, Work-for-Hire, and The Struggle of the Creative Precariat in the American Comic Book Industry Co-Chair: Ben Chappell Co-Chair: Elizabeth Esch Date Approved: 24 May 2019 iii Abstract The comic book industry has significant challenges with intellectual property rights. Comic books have rarely been treated as a serious art form or cultural phenomenon. It used to be that creating a comic book would be considered shameful or something done only as side work. Beginning in the 1990s, some comic creators were able to leverage enough cultural capital to influence more media. In the post-9/11 world, generic elements of superheroes began to resonate with audiences; superheroes fight against injustices and are able to confront the evils in today’s America. This has created a billion dollar, Oscar-award-winning industry of superhero movies, as well as allowed created comic book careers for artists and writers. -

Enhanced Webcomics”: an Analysis of the Merging Of

University of Amsterdam Spring Semester 2015 Department of Media Studies New Media and Digital Culture Supervisor: Dr. Erin La Cour Second reader: Dr. Dan Hassler-Forest MA Thesis “Enhanced Webcomics”: An Analysis of the Merging of Comics and New Media Josip Batinić 10848398 Grote Bickersstraat 62 f-1 1013 KS Amsterdam [email protected] 06 264 633 34 26 June 2015 Table of Contents 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 1 2. Defining Comics, Webcomics, and Enhanced comics ....................................................... 6 3. Literary Basis ...................................................................................................................... 11 4. Analysis ................................................................................................................................ 27 4.1 Infinite Canvas ................................................................................................................................. 27 4.2. Moving Image and Sound ............................................................................................................... 37 4.3 Co-Authorship and Reader-Driven Webcomics ............................................................................... 43 4.4 Interactivity ...................................................................................................................................... 49 5. Epilogue: A new frontier for comics ................................................................................ -

The Journal of Multimodal Rhetorics Vol

The Journal of Multimodal Rhetorics Vol. 3, Issue 1 Special Issue: Comics and/as Rhetoric Spring 2019 (3:1) 86 Sex-Education Comics: Feminist and Queer Approaches to Alternative Sex Education Michael J. Faris, Texas Tech University This article argues that sex-education comics serve as sponsors of readers’ sexual literacy and agency, providing an inclusive, feminist, and queer positionality that promotes sexuality as a techné, one that is not merely technical but also civic and relational. These comics don’t solely teach technical information about sex (like anatomy and preventing the spread of sexually transmitted diseases); they also provide material that explores the significance of sexuality in developing one’s identity and in being in relation with others. These comics take a feminist, queer, and inclusive positionality (in opposition to mainstream sex education and to normative regimes of sex, sexuality, and gender), deploy autobiography, prioritize emotions and relations, and provide technical information that shapes the attitudes of readers. Consequently, through the use of multiple modes in comics form, they teach sex and sexuality as a techné—civic practices that are generative of new ways of relating with others and being in the world. Introduction Mainstream school-based sex education has come under numerous critiques from scholars and activists for its ineffectiveness and harmful effects on youth. As critics have argued, sex education typically frames sex in terms of danger and risk, positioning youth as needing protection from those dangers and risks rather than treating them as sexual agents in their own right (Allen, 2007; Bay-Cheng, 2003). Further, these programs often reinforce heteronormativity (treating sex almost exclusively as penile–vaginal intercourse) and rigid gender norms. -

Lone Wolf and Cub Omnibus Volume 1 Ebook Free Download

LONE WOLF AND CUB OMNIBUS VOLUME 1 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Goseki Kojima,Kazuo Koike,Chris Warner | 712 pages | 04 Jun 2013 | DARK HORSE COMICS | 9781616551346 | English | Milwaukee, United States Lone Wolf and Cub Omnibus Volume 1 PDF Book A legendary manga, later adapted to film, this is a great action read, if a bit flawed. Ogami's reputation is fierce and he seeks justice and revenge. Masterless samurai called ronin took whatever work they could that used their skills. A quest for vengeance wouldn't be complete without a little poison. Jan 03, Malum rated it really liked it Shelves: manga. No worries -- I'm sure he'll be fine. He characters are not pretty boys and girls, they are real life people. Hebi-Zou , Tsuta Suzuki. The flow of time is uncertain throughout the series and it's unclear at time what order the events are in. Around page , I started to see the poetry in the dialogue and in Goseki Kojima'a At first I was almost disappointed with this series. Lean and well-written, there are nevertheless sometimes whole pages of nothing but the starkly beautiful illustrations telling volumes without the need for words. Nov 24, Quentin Wallace rated it it was amazing. Created by Kazuo Koike and Goseki Kojima, Lone Wolf and Cub has sold over a million copies of its first Dark Horse English-language editions, and this acclaimed masterpiece of graphic fiction is now available in larger format, value-priced editions. We learn about Bushido , the Way of the Warrior. Somewhat unexpected as I am a big manga and anime fan. -

Ron Garney Number 10 Spring 2005 $5

THE PROFESSIONAL “HOW-TO” MAGAZINE ON COMICS AND CARTOONING UP, UP, AND AWAY WITh the JLA’S RON GARNEY NUMBER 10 SPRING 2005 $5. 95 IN THE U.S.A. S u p e r m a n T M & © 2 0 0 5 D C C o m i c s . Comic Books to Comic Strips with The Phantom’s Graham Nolan letteriing a round-table discussion with todd kklleeiinn draping the human figure, part 2 by PLUS! bbrreett bblleevviinnss ADOBE ILLUSTRATOR TUTORIAL BY AALLBBEERRTTOO RRUUIIZZ!! THE PROFESSIONAL “HOW-TO” MAGAZINE ON COMICS & CARTOONING WWW.DRAWMAGAZINE.COM SPRING 2005 • VOL. 1, NO. 10 FEATURES Editor-in Chief • Michael Manley Designer • Eric Nolen-Weathington COVER STORY INTERVIEW WITH JLA PENCILLER Publisher • John Morrow RON GARNEY Logo Design • John Costanza 3 Proofreaders • John Morrow & Eric Nolen-Weathington Transcription • Steven Tice For more great information on cartooning and animation, visit our Web site at: http://www.drawmagazine.com Front Cover 25 Illustration by COMIC STRIPS PHANTOM AND REX MORGAN ARTIST Ron Garney GRAHAM NOLAN Coloring by Mike Manley LETTERING DISCUSSION 43 CONDUCTED BY TODD KLEIN SUBSCRIBE TO DRAW! Four quarterly issues: $20 US Standard Mail, $32 US First Class Mail ($40 Canada, Elsewhere: $44 Surface, $60 Airmail). ADOBE ILLUSTRATOR We accept US check, money order, Visa and Mastercard at TIPS: BITMAP TEXTURE FUN TwoMorrows, 10407 Bedfordtown Dr., Raleigh, NC 27614, 49 BY ALBERTO RUIZ (919) 449-0344, E-mail: [email protected] ADVERTISE IN DRAW! See page 2 for ad rates and specifications. BANANA TAIL DRAW! Spring 2005, Vol. 1, No. 10 was produced by Action Planet Inc. -

The Eternal Green Lantern

Roy Tho mas ’ Mean & Green Comics Fan zine GREEN GROW THE LANTTEERRNNSS $7.95 NODELL, KANE, In the USA & THE CREATION OF A No.102 LEGEND— TIMES TWO! June 2011 06 1 82658 27763 5 Green Lantern art TM & ©2011 DC Comics Vol. 3, No. 102 / June 2011 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Christopher Day Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Comic Crypt Editor TH Michael T. Gilbert NOW WI Editorial Honor Roll 16 PAGES Jerry G. Bails (founder) R! Ronn Foss, Biljo White OF COLO Mike Friedrich Proofreader Rob Smentek Cover Artists Mart Nodell, Gil Kane, & Terry Austin Contents Cover Colorists Writer/Editorial – “Caught In The Creative Act” . 2 Mart Nodell & Tom Ziuko The Eternal Green Lantern . 3 With Special Thanks to: Will Murray’s overview of the Emerald Gladiators of two comic book Ages. Heidi Amash Bob Hughes Henry Andrews Sean Howe “Marty Created ‘The Green Lantern’!” . 15 Finn Andreen Betty Tokar Jankovich Ger Apeldoorn Robert Kennedy Mart & Carrie Nodell interviewed about GL and other wonders by Shel Dorf. Terry Austin David Anthony Kraft Bob Bailey R. Gary Land “Life’s Not Over Yet!” . 31 Mike W. Barr Jim Ludwig Jim Beard Monroe Mayer Jack Mendelsohn on his comics and animation work (part 2), with Jim Amash. John Benson Jack Mendelsohn Jared Bond Raymond Miller Bob & Betty—& Archie & Betty . 44 Dominic Bongo Ken Moldoff An interview with the woman who probably inspired Betty Cooper—conducted by Shaun Clancy. Wendy Gaines Bucci Shelly Moldoff Mike Burkey Lynn Montana Glen Cadigan Brian K. -

Beyond Panels Interactive Storytelling: Developing a Framework for Highly Emotive Narrative Experiences on Mobile Devices

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2017 Beyond Panels Interactive Storytelling: Developing a Framework for Highly Emotive Narrative Experiences on Mobile Devices Michael Joseph Eakins University of Central Florida Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Eakins, Michael Joseph, "Beyond Panels Interactive Storytelling: Developing a Framework for Highly Emotive Narrative Experiences on Mobile Devices" (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 6272. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/6272 BEYOND PANELS INTERACTIVE STORYTELLING: DEVELOPING A FRAMEWORK FOR HIGHLY EMOTIVE NARRATIVE EXPERIENCES ON MOBILE DEVICES by MICHAEL JOSEPH EAKINS B.A. University of Central Florida, 2009 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Emerging Media in the School of Visual Arts and Design in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2017 Major Professor: Rudy McDaniel and Joseph Fanfarelli © 2017 Michael Eakins ii ABSTRACT Balancing passive and interactive experiences within a narrative experience is an area of research that has broad applicability to the video game, cinematic, and comic book industries. Each of these media formats has attempted various experiments in interactive experience. -

Moore Layout Original

Bibliography Within your dictionary, next to word “prolific” you’ll created with their respective co-creators/artists) printing of this issue was pulped by DC hierarchy find a photo of Alan Moore – who since his profes - because of a Marvel Co. feminine hygiene product ad. AMERICA’S BEST COMICS 64 PAGE GIANT – Tom sional writing debut in the late Seventies has written A few copies were saved from the company’s shred - Strong “Skull & Bones” – Art: H. Ramos & John hundreds of stories for a wide range of publications, der and are now costly collectibles) Totleben / “Jack B. Quick’s Amazing World of both in the United States and the UK, from child fare Science Part 1” – Art: Kevin Nowlan / Top Ten: THE LEAGUE OF EXTRAORDINARY GENTLEMEN like Star Wars to more adult publications such as “Deadfellas” – Art: Zander Cannon / “The FIRST (Volume One) #6 – “6: The Day of Be With Us” & Knave . We’ve organized the entries by publishers and First American” – Art: Sergio Aragonés / “The “Chapter 6: Allan and the Sundered Veil’s The listed every relevant work (comics, prose, articles, League Of Extraordinary Gentlemen Game” – Art: Awakening” – Art: Kevin O’Neill – 1999 artwork, reviews, etc...) written by the author accord - Kevin O’Neill / Splash Brannigan: “Specters from ingly. You’ll also see that I’ve made an emphasis on THE LEAGUE OF EXTRAORDINARY GENTLEMEN Projectors” – Art: Kyle Baker / Cobweb: “He Tied mentioning the title of all his penned stories because VOLUME 1 – Art: Kevin O’Neill – 2000 (Note: Me To a Buzzsaw (And It Felt Like a Kiss)” – Art: it is a pet peeve of mine when folks only remember Hardcover and softcover feature compilation of the Dame Darcy / “Jack B. -

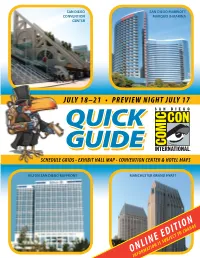

Quick Guide Is Online

SAN DIEGO SAN DIEGO MARRIOTT CONVENTION MARQUIS & MARINA CENTER JULY 18–21 • PREVIEW NIGHT JULY 17 QUICKQUICK GUIDEGUIDE SCHEDULE GRIDS • EXHIBIT HALL MAP • CONVENTION CENTER & HOTEL MAPS HILTON SAN DIEGO BAYFRONT MANCHESTER GRAND HYATT ONLINE EDITION INFORMATION IS SUBJECT TO CHANGE MAPu HOTELS AND SHUTTLE STOPS MAP 1 28 10 24 47 48 33 2 4 42 34 16 20 21 9 59 3 50 56 31 14 38 58 52 6 54 53 11 LYCEUM 57 THEATER 1 19 40 41 THANK YOU TO OUR GENEROUS SHUTTLE 36 30 SPONSOR FOR COMIC-CON 2013: 32 38 43 44 45 THANK YOU TO OUR GENEROUS SHUTTLE SPONSOR OF COMIC‐CON 2013 26 23 60 37 51 61 25 46 18 49 55 27 35 8 13 22 5 17 15 7 12 Shuttle Information ©2013 S�E�A�T Planners Incorporated® Subject to change ℡619‐921‐0173 www.seatplanners.com and traffic conditions MAP KEY • MAP #, LOCATION, ROUTE COLOR 1. Andaz San Diego GREEN 18. DoubleTree San Diego Mission Valley PURPLE 35. La Quinta Inn Mission Valley PURPLE 50. Sheraton Suites San Diego Symphony Hall GREEN 2. Bay Club Hotel and Marina TEALl 19. Embassy Suites San Diego Bay PINK 36. Manchester Grand Hyatt PINK 51. uTailgate–MTS Parking Lot ORANGE 3. Best Western Bayside Inn GREEN 20. Four Points by Sheraton SD Downtown GREEN 37. uOmni San Diego Hotel ORANGE 52. The Sofia Hotel BLUE 4. Best Western Island Palms Hotel and Marina TEAL 21. Hampton Inn San Diego Downtown PINK 38. One America Plaza | Amtrak BLUE 53. The US Grant San Diego BLUE 5.