Conserving Georgian and Victorian Terraced Housing a Guide to Managing Change Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ABSTRACT the Main Feature of a Conventional Terraced Housing Development Is Rows of Rectangular Shaped Houses with the Narrow Fa

MAKING A RETURN ON INVESTMENT IN PASSIVE ARCHITECTURE TERRACED HOUSES DEVELOPMENT Wan Rahmah Mohd Zaki Universiti Teknologi Malaysia(UiTM) Malaysia E-mail: [email protected] Abdul Hadi Nawawi Universiti Teknologi MalaysiaQJiTM) Malaysia E-mail: [email protected] Sabarinah Sh Ahmad Universiti Teknologi MalaysiaQJiTM) Malaysia E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT The main feature of a conventional terraced housing development is rows of rectangular shaped houses with the narrow facade as the frontage. Consequently, this limits natural cross ventilation and daylight penetration into the middle of the houses; and cause for unnecessary energy consumption on mechanical cooling and artijicial lighting to make the living spaces comfortable for occupants. Such inconsideration is mainly attributed to the optimum configuration of houses which offers the most economic return desired by the developer. Passive Architecture (PA) design strategies can make terraced houses more conducive for occupants as well as gives reasonable returns to the developer. The idea is demonstrated on a hypothetical double storeys terraced scheme in a 2.5 acre site whereby it is transformed intofour types of PA terraced houses development. The Return on Invesfment of the PA terraced houses is ascertained for two situations, ie., (i) fwed sales price for all types of house; and (ii) added premium to PA terraced houses due to the positive unintended effects such as low density housing, etc. If critical criteria for demand and supply in housing remain constant, it is found that PA terraced housing development offers competitive returns to the developer relative to the returns for conventional terraced housing scheme. Keyworh: Orientation, Indoor Comfort and Operational Energy 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Housing and Energy The recent public awareness on sustainability calls for housing to not only serves as a basic shelter but also to be energy efficient, i.e., designed to make occupants need low operational energy. -

Building an Adu

BUILDING AN ADU GUIDE TO ACCESSORY DWELLING UNITS 1 451 S. State Street, Room 406 Salt Lake City, UT 84114 - 5480 P.O. Box 145480 CONTENT 04 OVERVIEW 08 ELIGIBILITY 11 BUILDING AN ADU Types of ADU Configurations 14 ATTACHED ADUs Existing Space Conversion // Basement Conversion // This handbook provides general Home with Attached Garage // Addition to House Exterior guidelines for property owners 21 DETACHED ADUs Detached Unit // Detached Garage Conversion // who want to add an ADU to a Attached Above Garage // Attached to Existing Garage lot that already has an existing single-family home. However, it 30 PROCESS is recommended to work with a 35 FAQ City Planner to help you answer any questions and coordinate 37 GLOSSARY your application. 39 RESOURCES ADU regulations can change, www.slc.gov/planning visit our website to ensure latest version 1.1 // 05.2020 version of the guide. 2 3 OVERVIEW WHAT IS AN ADU? An accessory dwelling unit (ADU) is a complete secondary residential unit that can be added to a single-family residential lot. ADUs can be attached to or part of the primary residence, or be detached as a WHERE ARE WE? separate building in a backyard or a garage conversion. Utah is facing a housing shortage, with more An ADU provides completely separate living space people looking for a place to live than there are homes. including a kitchen, bathroom, and its own entryway. Low unemployment and an increasing population are driving a demand for housing. Growing SLC is the City’s adopted housing plan and is aimed at reducing the gap between supply and demand. -

Brief History of Architecture in N.C. Courthouses

MONUMENTS TO DEMOCRACY Architecture Styles in North Carolina Courthouses By Ava Barlow The judicial system, as one of three branches of government, is one of the main foundations of democracy. North Carolina’s earliest courthouses, none of which survived, were simple, small, frame or log structures. Ancillary buildings, such as a jail, clerk’s offi ce, and sheriff’s offi ce were built around them. As our nation developed, however, leaders gave careful consideration to the structures that would house important institutions – how they were to be designed and built, what symbols were to be used, and what building materials were to be used. Over time, fashion and design trends have changed, but ideals have remained. To refl ect those ideals, certain styles, symbols, and motifs have appeared and reappeared in the architecture of our government buildings, especially courthouses. This article attempts to explain the history behind the making of these landmarks in communities around the state. Georgian Federal Greek Revival Victorian Neo-Classical Pre – Independence 1780s – 1820 1820s – 1860s 1870s – 1905 Revival 1880s – 1930 Colonial Revival Art Deco Modernist Eco-Sustainable 1930 - 1950 1920 – 1950 1950s – 2000 2000 – present he development of architectural styles in North Carolina leaders and merchants would seek to have their towns chosen as a courthouses and our nation’s public buildings in general county seat to increase the prosperity, commerce, and recognition, and Trefl ects the development of our culture and history. The trends would sometimes donate money or land to build the courthouse. in architecture refl ect trends in art and the statements those trends make about us as a people. -

Proposed Terrace and Yard Plantings Ad-Hoc Committee

SASY Neighborhood Council Proposed Terrace and Yard Plantings Ad-Hoc Committee Purpose The purpose of this ad hoc committee is to research and analyze ordinances and practices related to terrace and yard plantings; report to the SASY Council as indicated; and work with SASY, city staff, and the SASY alderperson to update ordinances to better reflect SASY neighborhood and wider community values and expectations. Background A survey of 91 properties in the heart of the SASY neighborhood showed that the majority (69%) of terraces and front yards in the neighborhood are in violation of restrictive city of Madison ordinances which broadly prohibit many plantings in terraces and private front yards. For example, prohibited are anything but grass within two feet of the curb; plantings over two feet tall in terraces; plantings and fences over three feet high within a ten-foot triangle next to driveways in each front yard; any overhang of vegetation, including grass, over the sidewalk; erection of any permanent structure on terraces, including vegetable boxes; grass over eight inches tall, including ornamental grasses; bushes and trees on terraces that are not planted by the city; plantings in a triangle ten feet along a driveway and ten feet along the sidewalk in the private front yard of each house/apartment or building; and other requirements. The city inspects and cites property owners for violations of terrace and yard planting ordinances upon submission of a complaint. The only exception is for plantings and structures for the sole purpose of erosion control. The “violations” in the SASY neighborhood almost without exception appear to enhance rather than detract from the appearance of the property and neighborhood. -

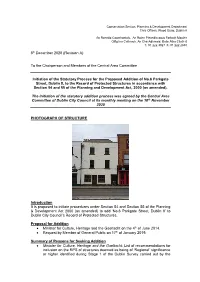

6 Parkgate Street, Dublin 8, to the Record of Protected Structures in Accordance with Section 54 and 55 of the Planning and Development Act, 2000 (As Amended)

Conservation Section, Planning & Development Department Civic Offices, Wood Quay, Dublin 8 An Rannóg Caomhantais, An Roinn Pleanála agus Forbairt Maoine Oifigí na Cathrach, An Ché Adhmaid, Baile Átha Cliath 8 T. 01 222 3927 F. 01 222 2830 8th December 2020 (Revision A) To the Chairperson and Members of the Central Area Committee Initiation of the Statutory Process for the Proposed Addition of No.6 Parkgate Street, Dublin 8, to the Record of Protected Structures in accordance with Section 54 and 55 of the Planning and Development Act, 2000 (as amended). The initiation of the statutory addition process was agreed by the Central Area Committee of Dublin City Council at its monthly meeting on the 10th November 2020 PHOTOGRAPH OF STRUCTURE Introduction It is proposed to initiate procedures under Section 54 and Section 55 of the Planning & Development Act 2000 (as amended) to add ‘No.6 Parkgate Street, Dublin 8’ to Dublin City Council’s Record of Protected Structures. Proposal for Addition Minister for Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht on the 4th of June 2014. Request by Member of General Public on 17th of January 2019. Summary of Reasons for Seeking Addition Minister for Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht: List of recommendations for inclusion on the RPS of structures deemed as being of ‘Regional’ significance or higher identified during Stage 1 of the Dublin Survey carried out by the National Inventory of Architectural Heritage. No.6 Parkgate Street, Dublin 8, together with the neighbouring properties at Nos.7 and 8 Parkgate Street, Dublin 8 has been assigned a ‘Regional’ rating. -

Estimating Parking Utilization in Multi-Family Residential Buildings in Washington, D.C

1 Estimating Parking Utilization in Multi-Family Residential Buildings in Washington, D.C. 2 3 Jonathan Rogers 4 Corresponding Author 5 District Department of Transportation 6 55 M Street SE 7 Washington, DC 20003 8 Tel: 202-671-3022; Fax: 202-671-0617; Email: [email protected] 9 10 Dan Emerine 11 D.C. Office of Planning 12 1100 4th Street SW, Suite E560 13 Washington, DC 20024 14 Tel: 202-442-8812; Fax: 202-442-7638 ; Email: [email protected] 15 16 Peter Haas 17 Center for Neighborhood Technology 18 2125 W. North Ave. 19 Chicago, Il 60647 20 Tel.: 773-269-4034; Fax: 773-278-3840; Email: [email protected] 21 22 David Jackson 23 Cambridge Systematics, Inc. 24 4800 Hampden Lane, Suite 800 25 Bethesda, MD 20901 26 Tel: 301-347-9108; Fax: 301-347-0101; Email: [email protected] 27 28 Peter Kauffmann 29 Gorove/Slade Associates, Inc. 30 1140 Connecticut Avenue, NW, Suite 600 31 Washington, DC 20036 32 Tel: 202-296-8625; Fax: 202-785-1276; Email: [email protected] 33 34 Rick Rybeck 35 Just Economics, LLC 36 1669 Columbia Rd., NW, Suite 116 37 Washington, DC 20009 38 Tel: 202-439-4176; Fax: 202-265-1288; Email: [email protected] 39 40 Ryan Westrom 41 District Department of Transportation 42 55 M Street SE 43 Washington, DC 20003 44 Tel: 202-671-2041; Fax: 202-671-0617; Email: [email protected] 45 46 Word count: 5,468 words text + 8 tables/figures x 250 words (each) = 7,468 words 1 Submission Date: November 13, 2015 1 ABSTRACT 2 The District Department of Transportation and the District of Columbia Office of Planning 3 recently led a research effort to understand how parking utilization in multi-family residential 4 buildings is related to neighborhood and building characteristics. -

A Short History of Georgian Architecture

A SHORT HISTORY OF GEORGIAN ARCHITECTURE Georgia is situated on the isthmus between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea. In the north it is bounded by the Main Caucasian Range, forming the frontier with Russia, Azerbaijan to the east and in the south by Armenia and Turkey. Geographically Georgia is the meeting place of the European and Asian continents and is located at the crossroads of western and eastern cultures. In classical sources eastern Georgia is called Iberia or Caucasian Iberia, while western Georgia was known to Greeks and Romans as Colchis. Georgia has an elongated form from east to west. Approximately in the centre in the Great Caucasian range extends downwards to the south Surami range, bisecting the country into western and eastern parts. Although this range is not high, it produces different climates on its western and eastern sides. In the western part the climate is milder and on the sea coast sub-tropical with frequent rains, while the eastern part is typically dry. Figure 1 Map of Georgia Georgian vernacular architecture The different climates in western and eastern Georgia, together with distinct local building materials and various cultural differences creates a diverse range of vernacular architectural styles. In western Georgia, because the climate is mild and the region has abundance of timber, vernacular architecture is characterised by timber buildings. Surrounding the timber houses are lawns and decorative trees, which rarely found in the rest of the country. The population and hamlets scattered in the landscape. In eastern Georgia, vernacular architecture is typified by Darbazi, a type of masonry building partially cut into ground and roofed by timber or stone (rarely) constructions known as Darbazi, from which the type derives its name. -

Movement on Stairs During Building Evacuations

NIST Technical Note 1839 Movement on Stairs During Building Evacuations Erica D. Kuligowski Richard D. Peacock Paul A. Reneke Emily Wiess Charles R. Hagwood Kristopher J. Overholt Rena P. Elkin Jason D. Averill Enrico Ronchi Bryan L. Hoskins Michael Spearpoint This publication is available free of charge from: http://dx.doi.org/10.6028/NIST.TN.1839 NIST Technical Note 1839 Movement on Stairs During Building Evacuations Erica D. Kuligowski Richard D. Peacock Paul A. Reneke Emily Wiess Kristopher J. Overholt Rena P. Elkin Jason D. Averill Fire Research Division Engineering Laboratory Charles R. Hagwood Statistical Engineering Division Information Technology Laboratory Enrico Ronchi Lund University Lund, Sweden Bryan L. Hoskins Oklahoma State University Stillwater, OK Michael Spearpoint University of Canterbury Christchurch, New Zealand This publication is available free of charge from http://dx.doi.org/10.6028/NIST.TN.1839 January 2015 U.S. Department of Commerce Penny Pritzker, Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology Willie May, Acting Under Secretary of Commerce for Standards and Technology and Acting Director Certain commercial entities, equipment, or materials may be identified in this document in order to describe an experimental procedure or concept adequately. Such identification is not intended to imply recommendation or endorsement by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, nor is it intended to imply that the entities, materials, or equipment are necessarily the best available for the purpose. National Institute of Standards and Technology Technical Note 1839 Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. Tech. Note 1839, 213 pages (January 2015) This publication is available free of charge from: http://dx.doi.org/10.6028/NIST.TN.1839 CODEN: NTNOEF Abstract The time that it takes an occupant population to reach safety when descending a stair during building evacuations is typically estimated by measureable engineering variables such as stair geometry, speed, stair density, and pre-observation delay. -

Old Market Character Appraisal Is Available Deadline of 21 February 2008

Conservation Area 16 Old Market Character Appraisal July 2008 www.bristol.gov.uk/conservation SA Hostel WINSFORD STREET FROME BRIDGE 1 PH 32 8 THRISS 26 to 30 E ET 24 2 LLST Old Market Convervation Area 1 2 20 R WADE STREET STRE 1 7 EET 3 Works N HA L AN Mm STREET 14 EST 8 Car Park LTTLE 6 7 RIVER STREET 2.0m 17 City Business Park 3 6 PH 15 to 11 Boundary of Conservation Area 20 PH 10 PH St Nicholas Church St Nicholas PH E STREET Church l Sub Sta Unive GP 1to32 Ho St Nicholas Lawford's G te TLE ANN usersal House 6 1 LIT Library 1to o15 DS GATE Lawford 11 t E Gate WADE STREE A WFOR T 1to18 D Wessex House 13 46 The Old Vica ge 59 4m ta 5 Car Park T 5 50 PH El T 16 City Business Park ub S 16 STREET S 18 19 PH RIVER INGTON ROAD 17 15 1 ELL NSTREET 1to22 W to 3 1 loucester 11 G House GREAT GEORGE STREE Somerset rence House GREAT AN 1to22 Ca TEMPLE WAY H Po ts o use TRINITY ROAD o44 (Community Centre) Friends Meeting TRINITY WALK House EY TCB 1t ERSL Telephone Exchange 1to17 41 ANE El Sub S Holy Trinity TCB to 48 Church Bristol City Mission Tyndall House 1to44 Po ice Station BRICK STREET Police Station 1to CLARENCE ROAD 1 17 22 20 9 Warehouse PH Jude St Coach and Horse 1to40 (PH) 8 E h Ves The 8 2 CLOS 1 sHo 85 1to2 HAYES 8 2 Warehouse 1 St Matthias try 23 25 81 ST MATTHIAS PARK 2 cel 6 1to 12 LANE E Subta 28 Th 90 41 S 40 (PH) 5 Cha 19 39 BRAGG'S 88 he Nave 75 86 3 21 T ER LANE TCB 84 7 T The LB 82 House 8 1 ES Old 1 The Tow r 0 78 Tannery30 UC St Matthias 51a 2 Guild 65 Heritage 16 Park GLO 1 7 12 29 5 7 0 t 3 o 31 62 5 6 495 2 4 10 18 33 -

Building a Safe Room Inside Your House COURTESY of NOAA/NSSL Includes Construction Plans and Cost Estimates

FEMA 320 FIRST EDITION October 1998 COURTESY OF NASA COURTESY Taking Shelter From the Storm: Building a Safe Room Inside Your House COURTESY OF NOAA/NSSL Includes Construction Plans and Cost Estimates Federal Emergency Management Agency Mitigation Directorate 500 C Street, SW. • Washington, DC 20472 www.fema.gov Acknowledgments This booklet and the construction drawings it contains would not have been possible without the pioneering work of the Wind Engineering Research Center at Texas Tech University, the diligent efforts of the design team, and the constructive suggestions of the reviewers. Design Team Reviewers Paul Tertell, P.E. Dennis Lee Project Officer Hurricane Program Manager Program Policy and Assessment Branch Mitigation Division Mitigation Directorate FEMA Region VI FEMA Denton, Texas Washington, DC Bill Massey Clifford Oliver, CEM Hurricane Program Manager Chief, Program Policy and Assessment Branch Mitigation Division Mitigation Directorate FEMA Region IV FEMA Atlanta, Georgia Washington, DC TIm Sheckler, P.E. Dr. Ernst Kiesling, P.E. Civil Engineer Professor of Civil Engineering National Earthquake Program Office Wind Engineering Research Center Mitigation Directorate Texas Tech University FEMA Lubbock, Texas Washington, DC Dr. Kishor Mehta, P.E. Dr. Richard Peterson Director, Wind Engineering Research Center Chairman, Department of Geosciences Texas Tech University Texas Tech University Lubbock, Texas Lubbock, Texas Russell Carter, E.I.T. Larry Tanner, P.E., R.A. Research Associate Research Associate Wind Engineering Research Center Wind Engineering Research Center Texas Tech University Texas Tech University Lubbock, Texas Lubbock, Texas William Coulbourne, P.E. Richard Vognild, P.E Structural Engineer Director, Technical Services Greenhorne & O’Mara, Inc. Southern Building Code Congress International Greenbelt, Maryland Birmingham, Alabama Jay Crandell, P.E. -

London Metropolitan Archives Victorian Society

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 VICTORIAN SOCIETY LMA/4460 Reference Description Dates BUILDING SUB-COMMITTEE CASE FILES BEDFORDSHIRE HUNTINGDON AND PETERBOROUGH LMA/4460/01/01/001 Hiawatha, 6 Goldington Road, Bedford, 1968 Bedfordshire CC (Houses): demolition threat 1 file Former reference: Z34 LMA/4460/01/01/002 Old Warden Park and village, Old Warden, 1970-1982 Bedfordshire CC (Houses): development in village and listing of features in park 1 file Former reference: WV12 and O13 LMA/4460/01/01/003 Milton Ernest Hall, Milton Ernest, Bedfordshire 1968-1985 CC (Houses): restoration and addition of fire escape 1 file Former reference: C5 LMA/4460/01/01/004 Queensgate Centre, Queen Street, 1975 Peterborough, Greater Peterborough (Shopping centres): demolition and new development 1 file Former reference: Z133 BERKSHIRE LMA/4460/01/02/001 Oakley Court, Windsor Road, Bray, Royal 1967-1980 Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead (Houses): listing and new development Includes letter from Sir John Betjeman 1 file Former reference: VM5 LMA/4460/01/02/002 Buildings adjacent to Church of All Saints, Boyn 1971-1995 Hill Maidenhead, Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead (Church buildings): poor condition and alterations 1 file Former reference: R5 LMA/4460/01/02/003 New town hall, Maidenhead, Royal Borough of 1959-1962 Windsor and Maidenhead (Town halls): new development 1 file Former reference: Z71 LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 2 VICTORIAN SOCIETY LMA/4460 Reference Description Dates LMA/4460/01/02/004 Library, Maidenhead, Royal Borough of 1966-1967 -

Toronto Arch.CDR

The Architectural Fashion of Toronto Residential Neighbourhoods Compiled By: RASEK ARCHITECTS LTD RASE K a r c h i t e c t s www.rasekarchitects.com f in 02 | The Architectural Fashion of Toronto Residential Neighbourhoods RASEK ARCHITECTS LTD Introduction Toronto Architectural Styles The majority of styled houses in the United States and Canada are The architecture of residential houses in Toronto is mainly influenced by its history and its culture. modeled on one of four principal architectural traditions: Ancient Classical, Renaissance Classical, Medieval or Modern. The majority of Toronto's older buildings are loosely modeled on architectural traditions of the British Empire, such as Georgian, Victorian, and Edwardian architecture. Toronto was traditionally a peripheral city in the The earliest, the Ancient Classical Tradition, is based upon the monuments architectural world, embracing styles and ideas developed in Europe and the United States with only limited of early Greece and Rome. local variation. A few unique styles of architecture have emerged in Toronto, such as the bay and gable style house and the Annex style house. The closely related Renaissance Classical Tradition stems from a revival of interest in classicism during the Renaissance, which began in Italy in the The late nineteenth century Torontonians embraced Victorian architecture and all of its diverse revival styles. 15th century. The two classical traditions, Ancient and Renaissance, share Victorian refers to the reign of Queen Victoria (1837-1901), called the Victorian era, during which period the many of the same architectural details. styles known as Victorian were used in construction. The styles often included interpretations and eclectic revivals of historic styles mixed with the introduction of Middle Eastern and Asian influences.