Beoubl R ;!H~Orpht Now I T Woul Terri E to Turn T E Ans Adrift = After Being Rescued from Such Tragic = = Circumstances

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Little Nazis KE V I N D

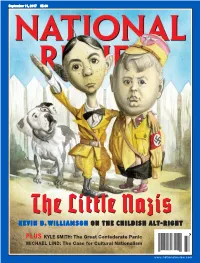

20170828 subscribers_cover61404-postal.qxd 8/22/2017 3:17 PM Page 1 September 11, 2017 $5.99 TheThe Little Nazis KE V I N D . W I L L I A M S O N O N T H E C HI L D I S H A L T- R I G H T $5.99 37 PLUS KYLE SMITH: The Great Confederate Panic MICHAEL LIND: The Case for Cultural Nationalism 0 73361 08155 1 www.nationalreview.com base_new_milliken-mar 22.qxd 1/3/2017 5:38 PM Page 1 !!!!!!!! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! "e Reagan Ranch Center ! 217 State Street National Headquarters ! 11480 Commerce Park Drive, Santa Barbara, California 93101 ! 888-USA-1776 Sixth Floor ! Reston, Virginia 20191 ! 800-USA-1776 TOC-FINAL_QXP-1127940144.qxp 8/23/2017 2:41 PM Page 1 Contents SEPTEMBER 11, 2017 | VOLUME LXIX, NO. 17 | www.nationalreview.com ON THE COVER Page 22 Lucy Caldwell on Jeff Flake The ‘N’ Word p. 15 Everybody is ten feet tall on the BOOKS, ARTS Internet, and that is why the & MANNERS Internet is where the alt-right really lives, one big online 35 THE DEATH OF FREUD E. Fuller Torrey reviews Freud: group-therapy session The Making of an Illusion, masquerading as a political by Frederick Crews. movement. Kevin D. Williamson 37 ILLUMINATIONS Michael Brendan Dougherty reviews Why Buddhism Is True: The COVER: ROMAN GENN Science and Philosophy of Meditation and Enlightenment, ARTICLES by Robert Wright. DIVIDED THEY STAND (OR FALL) by Ramesh Ponnuru 38 UNJUST PROSECUTION 12 David Bahnsen reviews The Anti-Trump Republicans are not facing their challenges. -

Bureau of Consumer Affairs Established by Mayor; Bernard W. (Buddy) Freedman to Serve As Director

L r THE MIDDLESEX COUNTY •I-/ xtm Serving Woodbridge Township, Cartcret and Edison Bnt««<J u 2nd etui Man Published At P. 0. Woodbridge, N. J. Woodbridge, N. J., Wednesday, February 26,1969 On Wcdnudiy TEN CENT3 Bureau of Consumer Affairs Established by Mayor; Bernard W. (Buddy) Freedman to Serve as Director By niJTII WOLK The mayor indicated that The mayor further staled, calls increase lo a large mim- slated thai the municipality is "As I said before, most of protect our people. This rm- some of Freedman's lesser hp felt the need was greai in her, a special telephone num- limited in its action because Ihe problems can he resolved reau is only aimed at un- WOODBRIDGE - Itfsin- duties may be given to some- scrupulous businessmen, not Ihe 'township, ' because it is her will be assigned, by a phone call. Sometimes ning today, Woodbridgc Town- one else so dial he will have not served by a Better Busi- ,,,„ .. ... , it cannot encroach upon other .11 the honest, established and ship will have a Bureau of Ihe time to devote to the op- ness Bureau. „ W« r™lw that ""?' "f agencies-stale and county. all one needs is a mediator, reliable merchants." Consumer Affairs. eration of the new bureau. the complaints we will re- "'Our job", he continued, someone to intercede." Freedman poinied mil (hat "I have been reading quite . , , . ," The announcement was Freedman is an attorney t eive wil be tjvi matu rs "will be (o encourage people May Seek Legislation as an attorney and a nirmher made by Mayor Ralph I'. -

"A Road to Peace and Freedom": the International Workers Order and The

“ A ROAD TO PEACE AND FREEDOM ” Robert M. Zecker “ A ROAD TO PEACE AND FREEDOM ” The International Workers Order and the Struggle for Economic Justice and Civil Rights, 1930–1954 TEMPLE UNIVERSITY PRESS Philadelphia • Rome • Tokyo TEMPLE UNIVERSITY PRESS Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19122 www.temple.edu/tempress Copyright © 2018 by Temple University—Of The Commonwealth System of Higher Education All rights reserved Published 2018 All reasonable attempts were made to locate the copyright holders for the materials published in this book. If you believe you may be one of them, please contact Temple University Press, and the publisher will include appropriate acknowledgment in subsequent editions of the book. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Zecker, Robert, 1962- author. Title: A road to peace and freedom : the International Workers Order and the struggle for economic justice and civil rights, 1930-1954 / Robert M. Zecker. Description: Philadelphia : Temple University Press, 2018. | Includes index. Identifiers: LCCN 2017035619| ISBN 9781439915158 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781439915165 (paper : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: International Workers Order. | International labor activities—History—20th century. | Labor unions—United States—History—20th century. | Working class—Societies, etc.—History—20th century. | Working class—United States—Societies, etc.—History—20th century. | Labor movement—United States—History—20th century. | Civil rights and socialism—United States—History—20th century. Classification: LCC HD6475.A2 -

THE Bush Freezes Assets of Suspected Terrorists

SHOWERS Live releases V Tuesday Scene reviews the fifth album, V, of Live, an alternative rock band from HIGH 55° Pennsylvania . SEPTEMBER25, LOW 43° Scene+ page 13 2001 THE The Independent Newspaper Serving Notre Dame and Saint Mary's VOL XXXV NO. 21 HTTP:! /OBSERVER.ND.EDU BOG discusses Strategic Plan ND alu01na CaDlpaigns for congressional seat congressional seat which U.S. By JASON McFARLEY Rep. Tim Roemer will vacate in News Editor 2003.- The newly expanded district It only took a few days on encompasses 12 counties, Notre Dame's campus in 1972 including St. Joseph, where for Kathleen Cekanski Farrand South Bend and Mishawaka are to realize she was in the right located. place. Cekanski Farrand became the In the fourth Democrat to declare her opening candidacy for the 2002 election. days of the Her campaign will be a grass semester roots effort that focuses on the that year district's constituents, she said. the first "We do not see this campaign t h a t as a sprint which focuses on KATIE LARSEN!The Observer University which candidate can raise the Residence Hall Association president Kathleen Nickson talks to students about plans for officials most amount of money the fastest," she said in her Aug. 18 upcoming Saint Mary's events at the Board of Governance meeting Monday. a d m i t t e d Cekanskl Farrand women as announcement, "But rather, we undergraduates - a large ban see this congressional campaign These areas of improvement "Even though students don't ner at the all-campus picnic as a marathon of meeting peo By SHANNON NELLIGAN have been translated into four see the long range of this plan greeted Cekanski Farrand, a ple and taking time to discuss News Writer major goals for the college to -it will directly effect them." first-year law student in the their concerns." complete within the next five The Board discussed ideas on third class of women to gradu "It's imporiant to meet as Mary-Jo Regan-Kubinski, co years. -

Fti^# 1990 ABSTRACT

p^ h' V ,,il II' js/ 1 A STUDY OF THE THEORY, EXPERIENCE AND TRENDS IN OPEN - PENO - CORRECTIONAL INSTITUTIONS WITH A FUNCTIONAL STUDY OF SAMPURNANAND CAMPS IN THE STATE OF UTTAR PRADESH ABSTRACT THESIS ^^-=^ ,,,_z_SlKBMlTTtD FOR, THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF nmm ViS^af/ft^i|Jl^//'(?^HWAI^CHANDRA VATSA ' 7^.1^''•-' - - 7t'~~ Under the Supervision st p^I5^ Mr. Qaiser Hayat mm^fi (Reader) -1 cri T?bq \^^ ^ FACULTY OF LAW ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY V ALIGARH (INDIA) fti^# 1990 ABSTRACT The present work is an attempt at an in-depth sttidy of THE THEORY, BXPBRIBNCB AND TRENDS IN OPEN PEHD CORRBCTIOMAl IIQTITUriOISS WITH A FUNOTIOML STUDY OP THE SAMPURMMND CAMPS IN THE STATE OP UTTAR PRADESH, The present researcher is aware that a considerable amount of reseai^h on prisons and prisoners exists. After a sur7ey of these research studies the researcher came to the conclusion that while there have been a large number of studies on prisons and prisoners from sociological and psychological points of view, there is yet to be a comprehensire study of open peno correctional institutions and theis in-nates from legal ppint of view and comparative social and economic cost benlfit ax^lysis and this is the task that the present enquirer has taken in hand. BOOK OSB It deals with the theory of opwij^eao correctional institutions. Chapter I is the statei^ent of the problem of study and includes the rationale, concept,, rt^seareh and delimitation of the area of study alongwith tlie utility of correctional research. Chapter II opens with \a) the Philosogliy of correction. -

Desert Magazine 1954 December

( TRAVEL GUIDE I PLACES TO STAY . GUIDE SERVICE . RESORTS I WHAT TO SEE . ... IN THE DESERT SOUTHWEST I I The most delightful winter climate in the United States! That is a fair description (if the SCOTTY'S FURNACE desert Southwest. The air is warm and CREEK INN dry and pure. The desert landscape CASTLE AMERICAN PLAN has been sterilized by the intense rays of summer's sun. Rocks are clean; FURNACE CREEK views to distant mountains are crystal DEATH clear. i, EUROPEAN PLAN ,.< Spend a few days, a week, or a life- VALLEY time on (he desert. Get close to the nature that transcends everyday prob- lems and conflicts. Enjoy viewing the distinctive vegetation of the desert: HOURLY TOURS Enjoy this luxurious desert oasis Joshua, Saguaro, Smoke trees, Yucca, OF FABULOUS LUXURY for rest, quiet, recreation: golf, Palo Verde, Date palms. tennis, riding, swimming, tour- Overnight Accommodations ing, and exploring. Sunny days, For the more active and adventur- cool nights.Excellent highways. ous, this is a recreational paradise. European from $6 dbl. For folders and reservations write 5410 Death Valley Hotel Rivers and lakes of the Southwest offer Mod. Am. from $13 dbl. Co., Death Valley, Calif. Or fishing, boating, exploration and the See your Travel Agent phone Furnace Creek Inn at ever-present scenic beauty. Golf, ten- Death Valley. Or call your local or write— travel agencies. Special discount nis, riding etc. continue unabated No through the winter. CASTLE HEAD OFFICE 1462 N. Stanley Ave Stove Pipe Wells Hotel Hollywood 46, Calif. Death Valley California NOW IS THE TIME Home of the Famous Annual Confirmed or Prospective BURRO-FLAPJACK Places to see CONTEST RIVER RATS Stove lJipc Wells Hotel was until his death in 1950 owned and operated by DON'T MISS IT! Plan now for a George Palmer Putnam, renowned author and explorer. -

The Romance of the Harem

-^<^^^^^^fe^/ THE IDOL OF BUDDHA THE ROMANCE OF THE HAREM BY MES. ANNA H. LEONOWENS, AUTHOR OF " THE ENGLISH GOVERNESS AT THE SIAMESE COURT. Illustrate*). THE EMERALD IDOL. BOSTON: JAMES R. OSGOOD AND COMPANY, Late Ticknor & Fields, axd Fields, Osgood, & Co. 1873. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1872, BY JAMES R. OSGOOD & CO., in the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington. University Press: Welch, Bigelow, & Co., Cambridge. PREFACE 91 rpRUTH is often stranger than fiction/' but so J- strange will some of the occurrences related in the following pages appear to Western readers, that I deem it necessary to state that they are also true. Most of the stories, incidents, and characters are known to me per- sonally to be real, while of such narratives as I received from others I can say that " I tell the tale as it was told to me," and written down by me at the time. In some cases I have substituted fictitious for real names, in order to shield from what might be undesired publicity persons still living. I gladly acknowledge my indebtedness to Mr. Francis George Shaw for valuable advice and aid in the prep- aration of this work for the press, and to Miss Sarah Bradley, daughter of the Eev. Dr. Bradley of Bangkok, for her kindness in providing me with photographs, otherwise unattainable, for some of the illustrations. New Brighton, Staten Island, September 13, 1872. DEDICATION. To the noble and devoted women whom I learned to know, to esteem, and to love in the city of the Nang Harm, I dedicate the following pages, containing a record of some of the events con- nected with their lives and sufferings. -

Samash Fall 2008 Gear Guide.Pdf

SAM ASH® 45-DAY SATISFACTION GUARANTEE: If you aren’t satisfied with your purchase for any reason, just return it within 30 days for a full refund or within 45 days for a full exchange. Returns must be in original condition with your Sam Ash receipt, all original packaging, accessories, manuals, and blank warranty cards. Limitations: For health reasons we do not accept returns of harmonicas and internal earphones. Please contact the manufacturer if defec- tive. We do not accept returns of open computer software, books, sheet music, and other easily copied materials. We do not accept returns of opened packages of strings, cartridges, styli, fog fluid, tubes, and cleaning products. Exceptions: There is a 15-day return period and a 15% restocking fee on microphones, mixers, speakers, power amps, rack effects, computers, recording, DJ, lighting, karaoke equipment, and pro workstations. There is no restocking fee on exchanges for like items; We do not accept returns on special order merchandise.; We reserve the right to require ID and deny return privileges to abusers of our policy.; Payment of Refunds: Refunds paid by the same method of payment as the original purchase whenever possible. Allow 15 business days for refund checks from our main office. SAM ASH® Best In The Business 50 State/60 Day BEST PRICE Guarantee: We Guarantee you the lowest price on your Sam Ash purchase. Sam Ash always beats the competition! Within 60 days, show us a lower price on the same product advertised by a US authorized dealer who has the product in stock, and we will beat that deal. -

Street: the Human Clay Free

FREE STREET: THE HUMAN CLAY PDF Lee Friedlander | 217 pages | 15 Nov 2016 | Yale University Press | 9780300221770 | English | New Haven, United States Human Clay | Gateway Center Human Clay is the second studio album by American rock band Creedreleased on September 28, through Wind-up Records. Produced by Street: The Human Clay Kurzwegit was the band's last album to feature Brian Marshallwho left the band in Augustuntil 's Full Circle. The album earned mixed to positive reviews from critics and was a massive commercial success, peaking at number one on the US Billboard and staying there for two weeks. The album spawned two singles Street: The Human Clay peaked in the top 10 of the Street: The Human Clay Hot : " Higher ", which peaked at number 7, and " With Arms Wide Open ", their only number one single. The album sold over Human Clay is the only Creed album to not have a title track. According to Mark Tremontithe album cover represents a crossroad which every man finds himself at in his life and the man of clay represented "our actions, that what we are is up to us, that we lead our own path and make our own destiny. During the summer ofbassist Brian Marshall began a spiral Street: The Human Clay alcoholism and addiction. While under the influence, Marshall threatened to beat up Tremonti, began missing band obligations, and attacking Stapp both verbally and online. The band had a meeting with management to discuss Marshall's future. Stapp and Tremonti supported Marshall going to rehab and attempted to talk Marshall into going, but at that point, Marshall was too far gone to recognize he needed help. -

Homelessness

EDITED BY: The Inclusion Working Group, Canadian Observatory on Homelessness HOMELESSNESS IS ONLY ONE PIECE OF MY PUZZLE Implications for Policy and Practice HOMELESSNESS IS ONLY ONE PIECE OF MY PUZZLE Implications for Policy and Practice © 2015 The Homeless Hub ISBN 978-1-77221-036-1 Inclusion Working Group, Canadian Observatory on Homelessness (Eds.), Homelessness is Only One Piece of My Puzzle: Implications for Policy and Practice. Toronto: The Homeless Hub Press. Hosted at the Homeless Hub: http://www.homelesshub.ca/onepieceofmypuzzle The Homeless Hub 6th Floor, Kaneff Tower, York University 4700 Keele Street Toronto, ON M3J 1P3 [email protected] www.homelesshub.ca Edited by: Inclusion Working Group, Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Cover and Interior Design: Sarah Hamdi, Patricia Lacroix Printed and bound by York University Printing Services This book is protected under a Creative Commons license that allows you to share, copy, distribute, and transmit the work for non-commercial purposes, provided you attribute it to the original source. The Homeless Hub is a Canadian Observatory on Homelessness (formerly known as the Canadian Homelessness Research Network) initiative. The goal of this book is to take homelessness research and relevant policy findings to new audiences. The Homeless Hub acknowledges, with thanks, the financial support of the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. The views expressed in this book are those of the Homeless Hub and/or the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of Canada. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Canadian Observatory would like to thank the members of its Inclusion Working Group for their contributions to, support of and patience throughout the development of this book. -

Greg's Movie List

Greg's Movie List # Vol Title # Vol Title 1 - 7 Splinters in Time 101 BM002 Alien Resurrection 2 - American Animals 102 BM002 Alien Versus Predator 3 American Flyers 103 BM002 Aliens 4 - Animal Kingdom 104 BM002 Back To The Future 5 - Animals United 105 BM002 Back To The Future Part II 6 - Bad Cat 106 BM002 Back To The Future Part III 7 - Beirut 107 BM002 Brother Bear 2 8 - Big Game 108 BM002 Cheaper by the Dozen 2 9 - Billionaire Boys Club 109 BM002 Devour 10 - Bird Box 110 BM002 Gods Must Be Crazy, The 11 - Blockers 111 BM002 Head of State 12 - Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice 112 BM002 Honeymooners, The 13 - Brahms: The Boy II 113 BM002 Intolerable Cruelty 14 - Bystander Theory, The 114 BM002 Johnny Dangerously 15 - Camouflage 115 BM002 Little Secrets 16 - Carry On Abroad 116 BM002 Lost In Translation 17 - Carry On Again Doctor 117 BM002 Monsters, Inc. 18 - Carry On At Your Convinience 118 BM002 Scary Movie 19 - Carry On Behind 119 BM002 Scary Movie 2 20 - Carry On Cabby 120 BM002 Scary Movie 3 21 - Carry On Camping 121 BM002 Van Helsing 22 - Carry On Cleo 122 BM002 Windtalkers 23 - Carry On Constable 123 BM003 About Schmidt 24 - Carry On Cowboy 124 BM003 Anaconda 25 - Carry On Cruising 125 BM003 Anacondas - The Hunt for Blood Orchid 26 - Carry On Dick 126 BM003 Freaky Friday 27 - Carry On Dick 127 BM003 Hannibal 28 - Carry On Doctor 128 BM003 Last Starfighter, The 29 - Carry On Don't Lose Your Head 129 BM003 Looney Tunes: Back In Action 30 - Carry On Emmannuelle 130 BM003 Major Payne 31 - Carry on England 131 BM003 Mickey 32 - Carry on Follow -

Presentación Del 100% Del Proyecto De Exploración De La Agenda

Presentación del 100% del proyecto de exploración de la agenda profesional Título: ¿Ha muerto el rock? Subtítulo: Análisis de las posibles causas de la declinación del rock en el S. XXI Autor: Rodolfo Marcelo Follari Asignatura: Producción Musical I (Eventos Musicales) Carrera: Producción Musical Fecha: 26/06/2020 Proyecto de exploración de la agenda profesional Título: ¿Ha muerto el rock? Subtítulo: Análisis de las posibles causas de la declinación del rock en el S. XXI 1 Resumen Desde mediados de la segunda década de este siglo, artistas, periodistas especializados, así como también profesionales del negocio de la industria musical, han comentado sobre la muerte de la música rock, responsabilizando a toda una serie de factores de negocio, socioculturales o musicales. Consecuentemente, y tal vez con una curiosidad inherente de un melómano alguien podría preguntarse ¿Cuáles son las razones que se esgrimen para argumentar semejante afirmación? ¿Cuáles son las implicancias? Este trabajo de investigación busca inicialmente recopilar y sacar a luz las explicaciones fundamentales que se emplean para debatir la muerte del rock como género musical y plantear algunas preguntas e hipótesis que den respuesta a esta problemática. Abstract Since the middle of the second decade of this century, artists and specialized journalists in music, as well as professionals from the music industry business, have commented on the death of rock music, blaming a whole range of business, socio-cultural or musical factors. Consequently, and perhaps with an inherent curiosity of a music lover, someone might ask: what are the reasons used to argue such a claim? What are the implications? This research paper initially seeks to compile and bring to light the fundamental explanations that are used to discuss the death of rock as a musical genre and raise some questions and hypotheses that respond to this problem.