Bedload Abrasion and the in Situ Fragmentation of Bivalve Shells

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Common Name: Chiton Class: Polyplacophora

Common Name: Chiton Class: Polyplacophora Scrapes algae off rock with radula 8 Overlapping Plates Phylum? Mollusca Class? Gastropoda Common name? Brown sea hare Class? Scaphopoda Common name? Tooth shell or tusk shell Mud Tentacle Foot Class? Gastropoda Common name? Limpet Phylum? Mollusca Class? Bivalvia Class? Gastropoda Common name? Brown sea hare Phylum? Mollusca Class? Gastropoda Common name? Nudibranch Class? Cephalopoda Cuttlefish Octopus Squid Nautilus Phylum? Mollusca Class? Gastropoda Most Bivalves are Filter Feeders A B E D C • A: Mantle • B: Gill • C: Mantle • D: Foot • E: Posterior adductor muscle I.D. Green: Foot I.D. Red Gills Three Body Regions 1. Head – Foot 2. Visceral Mass 3. Mantle A B C D • A: Radula • B: Mantle • C: Mouth • D: Foot What are these? Snail Radulas Dorsal HingeA Growth line UmboB (Anterior) Ventral ByssalC threads Mussel – View of Outer Shell • A: Hinge • B: Umbo • C: Byssal threads Internal Anatomy of the Bay Mussel A B C D • A: Labial palps • B: Mantle • C: Foot • D: Byssal threads NacreousB layer Posterior adductorC PeriostracumA muscle SiphonD Mantle Byssal threads E Internal Anatomy of the Bay Mussel • A: Periostracum • B: Nacreous layer • C: Posterior adductor muscle • D: Siphon • E: Mantle Byssal gland Mantle Gill Foot Labial palp Mantle Byssal threads Gill Byssal gland Mantle Foot Incurrent siphon Byssal Labial palp threads C D B A E • A: Foot • B: Gills • C: Posterior adductor muscle • D: Excurrent siphon • E: Incurrent siphon Heart G F H E D A B C • A: Foot • B: Gills • C: Mantle • D: Excurrent siphon • E: Incurrent siphon • F: Posterior adductor muscle • G: Labial palps • H: Anterior adductor muscle Siphon or 1. -

Silicified Eocene Molluscs from the Lower Murchison District, Southern Carnarvon Basin, Western Australia

[<ecords o{ the Western A uslralian Museum 24: 217--246 (2008). Silicified Eocene molluscs from the Lower Murchison district, Southern Carnarvon Basin, Western Australia Thomas A. Darragh1 and George W. Kendrick2.3 I Department of Invertebrate Palaeontology, Museum Victoria, 1'.0. Box 666, Melbourne, Victoria 3001, Australia. Email: tdarragh(il.Illuseum.vic.gov.au :' Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Western Australian Museum, Locked Bag 49, Welshpool D.C., Western Australia 6986, Australia. 1 School of Earth and Ceographical Sciences, The University of Western Australia, 35 Stirling Highway, Crawlev, Western Australia 6009, Australia. Abstract - Silicified Middle to Late Eocene shallow water sandstones outcropping in the Lower Murchison District near Kalbarri township contain a silicified fossil fauna including foraminifera, sponges, bryozoans, solitary corals, brachiopods, echinoids and molluscs. The known molluscan fauna consists of 51 species, comprising 2 cephalopods, 14 bivalves, 1 scaphopod and 34 gastropods. Of these taxa three are newly described, Cerithium lvilya, Zeacolpus bartol1i, and Lyria lamellatoplicata. 25 of these molluscs are identical to or closely comparable with taxa from the southern Australian Eocene. The occurrence of this fauna extends the Southeast Australian Province during the Eocene from southwest Western Australia along the west coast north to at least 27° present day south latitude; consequently the province is here renamed the Southern Australian Province. Keywords: siliceous fossils, Eocene, Kalbarri, molluscs, new taxa, Carnarvon Basin, biogeography, Southern Australian Province. INTRODUCTION The source deposit, a pallid to ferruginous silicified Eocene marine molluscan assemblages from sandstone, forms a weakly defined, low breakaway coastal sedimentary basins in southern Australia trending N-S and sloping gently westward. -

Field Identification Guide to the Living Marine Resources In

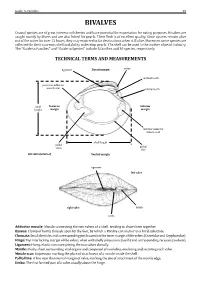

Guide to Families 29 BIVALVES Coastal species are of great interest to fisheries and have potential for exportation for eating purposes. Bivalves are caught mainly by divers and are also fished for pearls. Their flesh is of excellent quality. Since oysters remain alive out of the water for over 12 hours, they may exported to far destinations when still alive. Moreover, some species are collected for their nacreous shell and ability to develop pearls. The shell can be used in the mother of pearl industry. The “Guide to Families’’ andTECHNICAL ‘‘Guide to Species’’ TERMS include 5AND families MEASUREMENTS and 10 species, respectively. ligament Dorsal margin umbo posterior adductor cardinal tooth muscle scar lateral tooth Posterior Anterior margin margin shell height anterior adductor muscle scar pallial sinus pallial shell length line left valve (interior) Ventral margin ligament left valve right valve lunule umbo Adductor muscle: Byssus: Chomata: Muscle connecting the two valves of a shell, tending to draw them together. Hinge: Clump of horny threads spun by the foot, by which a Bivalve can anchor to a hard substrate. Ligament: Small denticles and corresponding pits located on the inner margin of the valves (Ostreidae and Gryphaeidae). Mantle: Top interlocking margin of the valves, often with shelly projections (teeth) and corresponding recesses (sockets). Muscle scar: Horny, elastic structure joining the two valves dorsally. Pallial line: Fleshy sheet surrounding vital organs and composed of two lobes, one lining and secreting each valve. Umbo: Impression marking the place of attachment of a muscle inside the shell. A line near the internal margin of valve, marking the site of attachment of the mantle edge. -

Clam Dissection Guideline

Clam Dissection Guideline BACKGROUND: Clams are bivalves, meaning that they have shells consisting of two halves, or valves. The valves are joined at the top, and the adductor muscles on each side hold the shell closed. If the adductor muscles are relaxed, the shell is pulled open by ligaments located on each side of the umbo. The clam's foot is used to dig down into the sand, and a pair of long incurrent and excurrent siphons that extrude from the clam's mantle out the side of the shell reach up to the water above (only the exit points for the siphons are shown). Clams are filter feeders. Water and food particles are drawn in through one siphon to the gills where tiny, hair-like cilia move the water, and the food is caught in mucus on the gills. From there, the food-mucus mixture is transported along a groove to the palps (mouth flaps) which push it into the clam's mouth. The second siphon carries away the water. The gills also draw oxygen from the water flow. The mantle, a thin membrane surrounding the body of the clam, secretes the shell. The oldest part of the clam shell is the umbo, and it is from the hinge area that the clam extends as it grows. I. Purpose: The purpose of this lab is to identify the internal and external structures of a mollusk by dissecting a clam. II. Materials: 2 pairs of safety goggles 1 paper towel 2 pairs of gloves 1 pair of scissors 1 preserved clam 2 pairs of forceps 1 dissecting tray 2 probes III. -

Freshwater Mussels of the Pacific Northwest

Freshwater Mussels of the Pacifi c Northwest Ethan Nedeau, Allan K. Smith, and Jen Stone Freshwater Mussels of the Pacifi c Northwest CONTENTS Part One: Introduction to Mussels..................1 What Are Freshwater Mussels?...................2 Life History..............................................3 Habitat..................................................5 Role in Ecosystems....................................6 Diversity and Distribution............................9 Conservation and Management................11 Searching for Mussels.............................13 Part Two: Field Guide................................15 Key Terms.............................................16 Identifi cation Key....................................17 Floaters: Genus Anodonta.......................19 California Floater...................................24 Winged Floater.....................................26 Oregon Floater......................................28 Western Floater.....................................30 Yukon Floater........................................32 Western Pearlshell.................................34 Western Ridged Mussel..........................38 Introduced Bivalves................................41 Selected Readings.................................43 www.watertenders.org AUTHORS Ethan Nedeau, biodrawversity, www.biodrawversity.com Allan K. Smith, Pacifi c Northwest Native Freshwater Mussel Workgroup Jen Stone, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Columbia River Fisheries Program Offi ce, Vancouver, WA ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Illustrations, -

Key to the Freshwater Bivalves of New Jersey

Key to the Freshwater Bivalves of New Jersey 1. a. shell with a very sharp posterior ridge, shaped like the marine mussel, Mytilus, generally less than 30 mm, and attached to a hard substrate with byssal threads.........................……………........................Zebra mussel b. animal without byssal threads attaching adult to substrate, with or without teeth but not with the above shape................................….............................2 2. a. valves with cardinal teeth and two sets of lateral teeth.......................…...............................3 b. valves with one set of lateral teeth and pseudocardinal teeth or without teeth.............................................................................................................5 3. a. shell thick and sturdy, beak bulbous and curving anteriorly………………….Atlantic rangia b. shell moderately thick, beak not bulbous nor curving…………………………………………...4 4. a. valves with serrated lateral teeth......................................……….........................Asian clam b. valves with smooth lateral teeth....................................................................Fingernail clam 5. a. hinge teeth absent.................................................................................................................6 b. hinge teeth present..............................................................................................................10 6. a. beaks not projecting above the hinge line................…………………........ Paper pondshell b. beaks projecting above -

Exputens) in Mexico, and a Review of All Species of This North American Subgenus

Natural History Museum /U, JH caY-^A 19*90 la Of Los Angeles County THE VELIGER © CMS, Inc., 1990 The Veliger 33(3):305-316 (July 2, 1990) First Occurrence of the Tethyan Bivalve Nayadina (.Exputens) in Mexico, and a Review of All Species of This North American Subgenus by RICHARD L. SQUIRES Department of Geological Sciences, California State University, Northridge, California 91330, USA Abstract. The malleid bivalve Nayadina (Exputens) has Old World Tethyan affinities but is known only from Eocene deposits in North America. Nayadina (Exputens) is reported for the first time from Mexico. About 50 specimens of N. (E.) batequensis sp. nov. were found in warm-water nearshore deposits of the middle lower Eocene part of the Bateque Formation, just south of Laguna San Ignacio, on the Pacific coast of Baja California Sur. The new species shows a wide range of morphologic variability especially where the beaks and auricles are located and how much they are developed. A review of the other species of Exputens, namely Nayadina (E.) llajasensis (Clark, 1934) from California and N. (E.) ocalensis (MacNeil, 1934) from Florida, Georgia, and North Carolina, revealed that they also have a wide range of morphologic variability. Nayadina (E.) alexi (Clark, 1934) is shown, herein, to be a junior synonym of N. (E.) llajasensis. The presence of a byssal sinus is recognized for the first time in Exputens. An epifaunal nestling mode of life, with attachment by byssus to hard substrate, can now be assumed for Exputens. INTRODUCTION species. It became necessary to thoroughly examine them, The macropaleontology of Eocene marine deposits in Baja and after such a study, it was found that the Bateque California Sur, Mexico, is largely an untouched subject. -

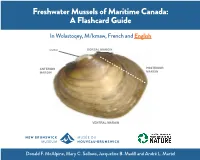

Freshwater Mussels of Maritime Canada: a Flashcard Guide

Freshwater Mussels of Maritime Canada: A Flashcard Guide In Wolastoqey, Mi’kmaw, French and English UMBO DORSAL MARGIN ANTERIOR POSTERIOR MARGIN MARGIN VENTRAL MARGIN Donald F. McAlpine, Mary C. Sollows, Jacqueline B. Madill and André L. Martel ISBN 978-0-919326-80-4 All photos copyright the Canadian Museum of Nature Acknowledgements: Funding for this publication provided by the Department of Fisheries and Oceans and the New Brunswick Museum. Special thanks to Ree Brennin Houston, Department of Fisheries and Oceans; Anne Hamilton, Brent Suttie, New Brunswick Archaeological Services Branch, and indigenous language translators Allan Tremblay (Wolastoqiyk), George Paul, Howard Augustine, and Karen Narvey (Mi’kmaw). Citation: McAlpine, D.F., M.C. Sollows, J. B. Madill, and A. L. Martel. 2018. Freshwater Mussels of Maritime Canada: A Flashcard Guide in Wolastoqey, Mi’kmaw, French and English. New Brunswick Museum, Saint John, New Brunswick, and Canadian Museum of Nature, Ottawa, Canada. Use in conjunction with Martel, A. L.,D.F. McAlpine, J. Madill, D. Sabine, A. Paquet, M. Pulsifer and M. Elderkin. 2010. Pp. 551-598. Freshwater Mussels (Bivalvia: Margaritiferidae, Unionidae) of the Atlantic Maritime Ecozone. In D.F. McAlpine and I.M. Smith (eds.). Assessment of Species Diversity in the Atlantic Maritime Ecozone. NRC Research Press, National Research Council of Canada, Ottawa, ON. 785 pp. Nedeau, E.J., M.A. McCollough, and B.I. Swartz. 2000. Freshwater Mussels of Maine. Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife, Augusta, ME, 118 pp. -

Identifying Freshwater Mussels (Unionoida)

Identifying freshwater mussels (Unionoida) and parasitic glochidia larvae from host fish gills: a molecular key to the North and Central European species Alexandra Zieritz1, Bernhard Gum1, Ralph Kuehn2 &JuergenGeist1 1Aquatic Systems Biology Unit, Department of Ecology and Ecosystem Management, Technische Universitat¨ Munchen,¨ Muhlenweg¨ 22, 85354 Freising, Germany 2Molecular Zoology Unit, Chair of Zoology, Department of Animal Science, Technische Universitat¨ Munchen,¨ Hans-Carl-von-Carlowitz-Platz 2, 85354 Freising, Germany Keywords Abstract Host–parasite interactions, morphological variability, PCR-RFLP, species identification, Freshwater mussels (order Unionoida) represent one of the most severely endan- Unionidae, wildlife management. gered groups of animals due to habitat destruction, introduction of nonnative species, and loss of host fishes, which their larvae (glochidia) are obligate parasites Correspondence on. Conservation efforts such as habitat restoration or restocking of host popu- Juergen Geist, Aquatic Systems Biology Unit, lations are currently hampered by difficulties in unionoid species identification Department of Ecology and Ecosystem by morphological means. Here we present the first complete molecular identifi- Management, Technische Universitat¨ Munchen,¨ Muhlenweg¨ 22, 85354 Freising, cation key for all seven indigenous North and Central European unionoid species Germany. Tel: +49 (0)8161 713767; and the nonnative Sinanodonta woodiana, facilitating quick, low-cost, and reliable Fax: +49 (0)8161 713477; identification of adult and larval specimens. Application of this restriction frag- E-mail: [email protected] ment length polymorphisms (RFLP) key resulted in 100% accurate assignment of 90 adult specimens from across the region by digestion of partial ITS-1 (where ITS Received: 2 December 2011; Revised: 26 is internal transcribed spacer) polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products in two to January 2012; Accepted: 6 February 2012 four single digestions with five restriction endonucleases. -

Pleistocene Molluscs from the Namaqualand Coast

ANNALS OF THE SOUTH AFRICAN MUSEUM ANNALE VAN DIE SUID-AFRIKAANSE MUSEUM Volume 52 Band July 1969 Julie Part 9 Dee! PLEISTOCENE MOLLUSCS FROM THE NAMAQUALAND COAST By A.J.CARRINGTON & B.F.KENSLEY are issued in parts at irregular intervals as material becomes available Obtainable from the South African Museum, P.O. Box 61, Cape Town word uitgegee in dele opongereelde tye na beskikbaarheid van stof OUT OF PRINT/UIT nRUK I, 2(1, 3, 5, 7-8), 3(1-2, 5, t.-p.i.), 5(2, 5, 7-9), 6(1, t.-p.i.), 7(1, 3), 8, 9(1-2), 10(1-3), 11(1-2, 7, t.-p.i.), 21, 24(2), 27, 31(1-3), 38, 44(4)· Price of this part/Prys van hierdie deel Rg.oo Trustees of the South African Museum © 1969 Printed in South Africa by In Suid-Afrika gedruk deur The Rustica Press, Pty., Ltd. Die Rustica-pers, Edms., Bpk. Court Road, Wynberg, Cape Courtweg, Wynberg, Kaap By A. ]. CARRINGTON & B. F. KENSLEY South African Museum, Cape Town (With plates 18 to 29 and I I figures) PAGE Introduction 189 Succession 190 Systematic discussion. 191 Acknowledgements 222 Summary. 222 References 223 INTRODUCTION In the course of an examination of the Tertiary to Recent sediments of the Namaqualand coast, being carried out by one of the authors (A.].C.), a collection of fossil molluscs was assembled from the Pleistocene horizons encountered in the area. The purpose of this paper is to introduce and describe some twenty species from this collection, including forms new to the South Mrican palaeontological literature. -

Missouri's Freshwater Mussels

Missouri mussel invaders Two exotic freshwater mussels, the Asian clam (Corbicula and can reproduce at a much faster rate than native mussels. MISSOURI’S fluminea) and the zebra mussel (Dreissena polymorpha), have Zebra mussels attach to any solid surface, including industrial found their way to Missouri. The Asian clam was introduced pipes, native mussels and snails and other zebra mussels. They into the western U.S. from Asia in the 1930s and quickly spread form dense clumps that suffocate and kill native mussels by eastward. Since 1968 it has spread rapidly throughout Missouri restricting feeding, breathing and other life functions. Freshwater and is most abundant in streams south of the Missouri River. In You can help stop the spread of these mussels by not moving the mid-1980s, zebra mussels hitched a ride in the ballast waters bait or boat well water from one stream to another; dump and of freighter ships traveling from Asia to the Great Lakes. They drain on the ground before leaving. Check all surfaces of your have rapidly moved into the Mississippi River basin and boat and trailer for zebra mussels and destroy them, along with westward to Oklahoma. vegetation caught on the boat or trailer. Wash with hot (104˚F) Asian clam and zebra mussel larvae have an advantage here water at a carwash and allow all surfaces to dry in the sun for at because they don’t require a fish host to reach a juvenile stage least five days before boating again. MusselsMusselsSue Bruenderman, Janet Sternburg and Chris Barnhart Zebra mussels attached to a native mussel JIM RATHERT ZEBRA CHRIS BARNHART ASIAN CLAM MUSSEL Shells are very common statewide in rivers, ponds and reservoirs A female can produce more than a million larvae at one time, and are often found on banks and gravel bars. -

The Freshwater Bivalve Mollusca (Unionidae, Sphaeriidae, Corbiculidae) of the Savannah River Plant, South Carolina

SRQ-NERp·3 The Freshwater Bivalve Mollusca (Unionidae, Sphaeriidae, Corbiculidae) of the Savannah River Plant, South Carolina by Joseph C. Britton and Samuel L. H. Fuller A Publication of the Savannah River Plant National Environmental Research Park Program United States Department of Energy ...---------NOTICE ---------, This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by the United States Government. Neither the United States nor the United States Depart mentof Energy.nor any of theircontractors, subcontractors,or theiremploy ees, makes any warranty. express or implied or assumes any legalliabilityor responsibilityfor the accuracy, completenessor usefulnessofanyinformation, apparatus, product or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. A PUBLICATION OF DOE'S SAVANNAH RIVER PLANT NATIONAL ENVIRONMENT RESEARCH PARK Copies may be obtained from NOVEMBER 1980 Savannah River Ecology Laboratory SRO-NERP-3 THE FRESHWATER BIVALVE MOLLUSCA (UNIONIDAE, SPHAERIIDAE, CORBICULIDAEj OF THE SAVANNAH RIVER PLANT, SOUTH CAROLINA by JOSEPH C. BRITTON Department of Biology Texas Christian University Fort Worth, Texas 76129 and SAMUEL L. H. FULLER Academy of Natural Sciences at Philadelphia Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Prepared Under the Auspices of The Savannah River Ecology Laboratory and Edited by Michael H. Smith and I. Lehr Brisbin, Jr. 1979 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 1 STUDY AREA " 1 LIST OF BIVALVE MOLLUSKS AT THE SAVANNAH RIVER PLANT............................................ 1 ECOLOGICAL