Mixed–Conifer Forests in Southwest Colorado

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Oklahoma Graduate College

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE POTENTIAL FIELD STUDIES OF THE CENTRAL SAN LUIS BASIN AND SAN JUAN MOUNTAINS, COLORADO AND NEW MEXICO, AND SOUTHERN AND WESTERN AFGHANISTAN A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By BENJAMIN JOHN DRENTH Norman, Oklahoma 2009 POTENTIAL FIELD STUDIES OF THE CENTRAL SAN LUIS BASIN AND SAN JUAN MOUNTAINS, COLORADO AND NEW MEXICO, AND SOUTHERN AND WESTERN AFGHANISTAN A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE CONOCOPHILLIPS SCHOOL OF GEOLOGY AND GEOPHYSICS BY _______________________________ Dr. G. Randy Keller, Chair _______________________________ Dr. V.J.S. Grauch _______________________________ Dr. Carol Finn _______________________________ Dr. R. Douglas Elmore _______________________________ Dr. Ze’ev Reches _______________________________ Dr. Carl Sondergeld © Copyright by BENJAMIN JOHN DRENTH 2009 All Rights Reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction…………………………………………………………………………..……1 Chapter A: Geophysical Constraints on Rio Grande Rift Structure in the Central San Luis Basin, Colorado and New Mexico………………………………………………………...2 Chapter B: A Geophysical Study of the San Juan Mountains Batholith, southwestern Colorado………………………………………………………………………………….61 Chapter C: Geophysical Expression of Intrusions and Tectonic Blocks of Southern and Western Afghanistan…………………………………………………………………....110 Conclusions……………………………………………………………………………..154 iv LIST OF TABLES Chapter A: Geophysical Constraints on Rio Grande Rift Structure in the Central -

Pine River Ranches CWPP Has Been Developed in Response to the Healthy Forests Restoration Act of 2003 (HFRA)

Pine River Ranches Community Wildfire Protection Plan July 2012 Prepared for: Pine River Ranches Land Owners Association Bayfield, Colorado and Upper Pine River Fire Protection District Bayfield, Colorado Prepared by: Short Forestry, LLC 9582 Road 35.4 Mancos, Colorado 81328 Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................... 3 2. BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................... 3 A. Location..................................................................................................................... 3 B. Community ............................................................................................................... 3 C. Local Fire History .................................................................................................... 4 D. Recent Wildfire Preparedness Activities ............................................................... 5 3. PLAN AREA ................................................................................................................. 5 A. Boundaries ................................................................................................................ 5 B. Private Land Characteristics .................................................................................. 6 C. Public Land Characteristics.................................................................................... 7 D. Fire Protection......................................................................................................... -

U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Locatable Mineral Reports for Colorado, South Dakota, and Wyoming provided to the U.S. Forest Service in Fiscal Years 1996 and 1997 by Anna B. Wilson Open File Report OF 97-535 1997 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) editorial standards or with the North American Stratigraphic Code. Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. CONTENTS page INTRODUCTION ................................................................... 1 COLORADO ...................................................................... 2 Arapaho National Forest (administered by White River National Forest) Slate Creek .................................................................. 3 Arapaho and Roosevelt National Forests Winter Park Properties (Raintree) ............................................... 15 Gunnison and White River National Forests Mountain Coal Company ...................................................... 17 Pike National Forest Land Use Resource Center .................................................... 28 Pike and San Isabel National Forests Shepard and Associates ....................................................... 36 Roosevelt National Forest Larry and Vi Carpenter ....................................................... 52 Routt National Forest Smith Rancho ............................................................... 55 San Juan National -

Historical Range of Variability and Current Landscape Condition Analysis: South Central Highlands Section, Southwestern Colorado & Northwestern New Mexico

Historical Range of Variability and Current Landscape Condition Analysis: South Central Highlands Section, Southwestern Colorado & Northwestern New Mexico William H. Romme, M. Lisa Floyd, David Hanna with contributions by Elisabeth J. Bartlett, Michele Crist, Dan Green, Henri D. Grissino-Mayer, J. Page Lindsey, Kevin McGarigal, & Jeffery S.Redders Produced by the Colorado Forest Restoration Institute at Colorado State University, and Region 2 of the U.S. Forest Service May 12, 2009 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY … p 5 AUTHORS’ AFFILIATIONS … p 16 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS … p 16 CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION A. Objectives and Organization of This Report … p 17 B. Overview of Physical Geography and Vegetation … p 19 C. Climate Variability in Space and Time … p 21 1. Geographic Patterns in Climate 2. Long-Term Variability in Climate D. Reference Conditions: Concept and Application … p 25 1. Historical Range of Variability (HRV) Concept 2. The Reference Period for this Analysis 3. Human Residents and Influences during the Reference Period E. Overview of Integrated Ecosystem Management … p 30 F. Literature Cited … p 34 CHAPTER II. PONDEROSA PINE FORESTS A. Vegetation Structure and Composition … p 39 B. Reference Conditions … p 40 1. Reference Period Fire Regimes 2. Other agents of disturbance 3. Pre-1870 stand structures C. Legacies of Euro-American Settlement and Current Conditions … p 67 1. Logging (“High-Grading”) in the Late 1800s and Early 1900s 2. Excessive Livestock Grazing in the Late 1800s and Early 1900s 3. Fire Exclusion Since the Late 1800s 4. Interactions: Logging, Grazing, Fire, Climate, and the Forests of Today D. Summary … p 83 E. Literature Cited … p 84 CHAPTER III. -

San Juan National Forest Outreach Notice

San Juan National Forest Outreach Notice SAN JUAN NATIONAL FOREST (Rangeland Management Specialist) (GS-0454-9) Dolores Ranger District Notice valid through 11/22/2013 Position Title: Rangeland Management Specialist Organizational Unit: Dolores Ranger District, San Juan National Forest Series: GS-0454 Grade: 9 Duty Location City: Dolores Duty Location State: Colorado Position Type: Permanent Full Time Primary Contact: Heather Musclow Post Notice Through: 11/22/2013 Vacancy Announcement: Anticipated on or around December 21, 2013 THE POSITION This position serves as Rangeland Management Specialist for the Dolores Ranger District on the San Juan National Forest in southwest Colorado. The incumbent is supervised by the Supervisory Rangeland Management Specialist with duty station in Dolores, Colorado. The position is permanent full time. Duties include; 1) Prepares allotment management plans, determining proper stocking, rotation schemes, and other appropriate range management applications, 2) Gathers, monitors, analyzes, interprets, and evaluates data to determine if land management, economic, and social goals and objectives identified for the land involved are being met, 3) Provides information and guidance on routine rangeland management issues and projects to coworkers, supervisor, landowners, affected groups and permittees, and 4) Makes recommendations and provides alternatives on the need, feasibility, design and layout of specific rangeland management practices. This position requires extensive travel, often on horseback, across the 600,000 acre District. MAJOR DUTIES Assists and participates in development of plans and programs for rangeland management by collecting data for grazing allotment plans and advising management as to logical division of allotments into units, what improvements are needed, and what management practices are needed in order to meet long- term objectives. -

Colorado Fourteeners Checklist

Colorado Fourteeners Checklist Rank Mountain Peak Mountain Range Elevation Date Climbed 1 Mount Elbert Sawatch Range 14,440 ft 2 Mount Massive Sawatch Range 14,428 ft 3 Mount Harvard Sawatch Range 14,421 ft 4 Blanca Peak Sangre de Cristo Range 14,351 ft 5 La Plata Peak Sawatch Range 14,343 ft 6 Uncompahgre Peak San Juan Mountains 14,321 ft 7 Crestone Peak Sangre de Cristo Range 14,300 ft 8 Mount Lincoln Mosquito Range 14,293 ft 9 Castle Peak Elk Mountains 14,279 ft 10 Grays Peak Front Range 14,278 ft 11 Mount Antero Sawatch Range 14,276 ft 12 Torreys Peak Front Range 14,275 ft 13 Quandary Peak Mosquito Range 14,271 ft 14 Mount Evans Front Range 14,271 ft 15 Longs Peak Front Range 14,259 ft 16 Mount Wilson San Miguel Mountains 14,252 ft 17 Mount Shavano Sawatch Range 14,231 ft 18 Mount Princeton Sawatch Range 14,204 ft 19 Mount Belford Sawatch Range 14,203 ft 20 Crestone Needle Sangre de Cristo Range 14,203 ft 21 Mount Yale Sawatch Range 14,200 ft 22 Mount Bross Mosquito Range 14,178 ft 23 Kit Carson Mountain Sangre de Cristo Range 14,171 ft 24 Maroon Peak Elk Mountains 14,163 ft 25 Tabeguache Peak Sawatch Range 14,162 ft 26 Mount Oxford Collegiate Peaks 14,160 ft 27 Mount Sneffels Sneffels Range 14,158 ft 28 Mount Democrat Mosquito Range 14,155 ft 29 Capitol Peak Elk Mountains 14,137 ft 30 Pikes Peak Front Range 14,115 ft 31 Snowmass Mountain Elk Mountains 14,099 ft 32 Windom Peak Needle Mountains 14,093 ft 33 Mount Eolus San Juan Mountains 14,090 ft 34 Challenger Point Sangre de Cristo Range 14,087 ft 35 Mount Columbia Sawatch Range -

Late Pleistocene Glacial Equilibrium-Line Altitudes in the Colorado Front Range: a Comparison of Methods

QUATERNARY RESEARCH l&289-310 (1982) Late Pleistocene Glacial Equilibrium-Line Altitudes in the Colorado Front Range: A Comparison of Methods THOMAS C. MEIERDING Department of Geography and Center For Climatic Research, University of Delaware, Newark, Delaware 19711 Received July 6, 1982 Six methods for approximating late Pleistocene (Pinedale) equilibrium-line altitudes (ELAs) are compared for rapidity of data collection and error (RMSE) from first-order trend surfaces, using the Colorado Front Range. Trend surfaces computed from rapidly applied techniques, such as glacia- tion threshold, median altitude of small reconstructed glaciers, and altitude of lowest cirque floors have relatively high RMSEs @I- 186 m) because they are subjectively derived and are based on small glaciers sensitive to microclimatic variability. Surfaces computed for accumulation-area ratios (AARs) and toe-to-headwall altitude ratios (THARs) of large reconstructed glaciers show that an AAR of 0.65 and a THAR of 0.40 have the lowest RMSEs (about 80 m) and provide the same mean ELA estimate (about 3160 m) as that of the more subjectively derived maximum altitudes of Pinedale lateral moraines (RMSE = 149 m). Second-order trend surfaces demonstrate low ELAs in the latitudinal center of the Front Range, perhaps due to higher winter accumulation there. The mountains do not presently reach the ELA for large glaciers, and small Front Range cirque glaciers are not comparable to small glaciers existing during Pinedale time. Therefore, Pleistocene ELA depression and consequent temperature depression cannot reliably be ascertained from the calcu- lated ELA surfaces. INTRODUCTION existed in alpine regions (Charlesworth, Glacial equilibrium-line altitudes (ELAs) 1957; ostrem, 1966; Flint, 1971; Andrews, have been widely used to infer present and 1975). -

Glade Ranger Station State Register Nomination, 5DL

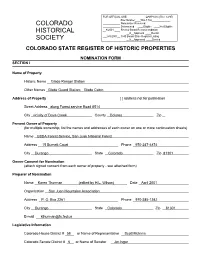

FOR OFFICIAL USE: OAHP1414 (Rev. 12/97) Site Number____5DL.1792_____________ COLORADO ____________ Nomination Received ____________ Determined ____Eligible ____Not Eligible __8/2001 ____ Review Board Recommendation HISTORICAL __X__Approval ____Denial ___8/8/2001__ CHS Board State Register Listing SOCIETY __X__Approved ____Denied COLORADO STATE REGISTER OF HISTORIC PROPERTIES NOMINATION FORM SECTION I Name of Property Historic Name Glade Ranger Station Other Names Glade Guard Station; Glade Cabin Address of Property [ ] address not for publication Street Address along Forest service Road #514 City vicinity of Dove Creek County Dolores Zip Present Owner of Property (for multiple ownership, list the names and addresses of each owner on one or more continuation sheets) Name USDA Forest Service, San Juan National Forest Address 15 Burnett Court Phone 970-247-4874 City Durango State Colorado Zip 81301 Owner Consent for Nomination (attach signed consent from each owner of property - see attached form) Preparer of Nomination Name Karen Thurman (edited by H.L. Wilson) Date April 2001 Organization San Juan Mountains Association Address P. O. Box 2261 Phone 970-385-1242 City Durango State Colorado Zip 81301 E-mail [email protected] Legislative Information Colorado House District # 58 or Name of Representative Scott McInnis Colorado Senate District # 6 or Name of Senator Jim Isgar COLORADO STATE REGISTER OF HISTORIC PROPERTIES Property Name Glade Ranger Station SECTION II Classification of Property Type [ X ] building(s) [ ] district [ ] site [ -

Geochronology Database for Central Colorado

Geochronology Database for Central Colorado Data Series 489 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Geochronology Database for Central Colorado By T.L. Klein, K.V. Evans, and E.H. DeWitt Data Series 489 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2010 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1-888-ASK-USGS For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: T.L. Klein, K.V. Evans, and E.H. DeWitt, 2009, Geochronology database for central Colorado: U.S. Geological Survey Data Series 489, 13 p. iii Contents Abstract ...........................................................................................................................................................1 Introduction.....................................................................................................................................................1 -

Social-Ecological Climate Resilience Southwest Colorado

SOCIAL-ECOLOGICAL CLIMATE RESILIENCE SOUTHWEST COLORADO Colorado Natural Heritage Program Salt Lake Denver SERVING San Juan SOUTHWEST Mountains COLORADO & FOUR CORNERS where the Rocky Mountains dive into the Southwestern desert Flagstaff Albuquerque SANDSTONE & RED ROCK DESERT COLORADO PLATEAU MEETS THE ROCKIES Project Goals To integrate climate science into decision-making • Build knowledge of social-ecological climate vulnerabilities to inform planning • Create scenarios and ecological models to facilitate decision-making under uncertainty • Develop and prioritize adaptive capacities and institutional arrangements • Document best practices for bringing climate science into decision-making 69% TOTAL LAND BASE = PUBLIC LANDS • Range 40-89% IMAGE OF THE OLD WEST IMAGE OF NEW WEST TOURISM- 33% AG/RANCH- 1% MINERALS/ AMENITY/SECOND OIL & GAS- 8% HOMES - 15% Ecological-Climate-Social CLIMATE SYSTEM Project Focus Knowledge ECOLOGICAL SOCIAL Livelihoods Ecosystems SYSTEMS SYSTEM Governance Species Culture Functions Values Processes Choose four The How adaptation targets Understand Current Develop three Management and Context climate and narrative scenarios Monitor and Evaluate Develop Range of Future Changes Conduct interviews , focus groups, and workshops Implement Identify Priority Actions Concerns Develop Plan for Select Priority Action Strategies Develop ecological response models Modified from Stein et al. 2014, Cross et al, and a whole lot of others Priorities Capacity Policies Resources The What Understand Current Management and Context Invasives Drought Monitor and Flooding Evaluate Develop Range of Future Changes Fire Insects & Disease Implement Identify Priority Impacts Actions Concerns Concerns Conflicts Strategies Develop Plan for Select Priority Action Strategies Resources Barriers Coordinated Actions Practice changes Enabling conditions Policy Changes No Regrets Modified from Stein et al. -

San Juan National Forest

SAN JUAN NATIONAL FOREST Colorado UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE V 5 FOREST SERVICE t~~/~ Rocky Mountain Region Denver, Colorado Cover Page. — Chimney Rock, San Juan National Forest F406922 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1942 * DEPOSITED BY T,HE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA San Juan National Forest CAN JUAN NATIONAL FOREST is located in the southwestern part of Colorado, south and west of the Continental Divide, and extends, from the headwaters of the Navajo River westward to the La Plata Moun- \ tains. It is named after the San Juan River, the principal river drainage y in this section of the State, which, with its tributaries in Colorado, drains the entire area within the forest. It contains a gross area of 1,444,953 ^ acres, of which 1,255,977 are Government land under Forest Service administration, and 188,976 are State and privately owned. The forest was created by proclamation of President Theodore Roosevelt on June 3, 1905. RICH IN HISTORY The San Juan country records the march of time from prehistoric man through the days of early explorers and the exploits of modern pioneers, each group of which has left its mark upon the land. The earliest signs of habitation by man were left by the cliff and mound dwellers. Currently with or following this period the inhabitants were the ancestors of the present tribes of Indians, the Navajos and the Utes. After the middle of the eighteenth century the early Spanish explorers and traders made their advent into this section of the new world in increasing numbers. -

Dollar General | Romeo, Co

OFFERING MEMORANDUM 222 MAIN ST | ROMEO, CO PRICE: $1,794,000 | CAP: 5.35% REPRESENTATIVE PHOTOS DOLLAR GENERAL | ROMEO, CO EXECUTIVE SUMMARY PRICE CAP NOI $1,794,000 5.35% $95,989 LOCATION 222 MAIN ST. ROMEO, CO 81148 LEASE TYPE ABSOLUTE NNN LEASE EXPIRATION MAY 31ST, 2035 LESSEE DOLLAR GENERAL GUARANTOR CORPORATE OPTIONS 3 5YEAR OPTIONS INCREASES 10% IN OPTION PERIODS FLAT LEASE DURING INITIAL TERM LAND SIZE ±0.80 ACRES BUILDING SIZE ±9,026 SQUARE FEET ROFR NO REPRESENTATIVE PHOTOS DOLLAR GENERAL | ROMEO, CO This property has an absolute NNN lease that will expire May 31st, 2030. There are (3) 5-year options and 10% BANG REALTY IS PLEASED TO BE increases in the option periods with a flat lease during the initial term. The building is ±9,026 square feet and sits on THE EXCLUSIVE LISTING ±0.80 acres of land. The property was built in 2020. The property has a corporate guarantee and the lessee is Dollar BROKERAGE FOR DOLLAR General. This property is located off Main St and hwy 285. This Dollar General location is also only ±16 miles from the GENERAL IN ROMEO, COLORADO. San Luis Valley Regional Airport and ±20 miles from the city of Alamosa. DOLLAR GENERAL | ROMEO, CO REPRESENTATIVE PHOTOS PROPERTY OVERVIEW • Corporate Guarantee • Absolute NNN • New Construction (2020) • 14 Years Remaining • 20 Miles from San Luis Valley Regional Airport ABOUT ROMEO | COLORADO Romeo is a town located in Conejos County, Colorado. As the county seat and the most populous municipality of Alamosa County, Alamosa is steadily growing with extensive construction and improvements to infrastructure and local retail centers.