Copenhagen | Conquering the Waterfront

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legepladser I Københavns Kommune

LEGEPLADSER I KØBENHAVNS KOMMUNE LEGEPLADSER BRØNSHØJ, HUSUM AMAGER I KØBENHAVNS Gyngemosen - ved Langhusvej (3-14 år) Prags Boulevard - Prags Boulevard (Fra 6 år) Sundbyvester Plads (3-16 år) KOMMUNE Naturlegeplads i udkanten af mosen. Pilehytter, forhindrings- Prags Boulevard har syv aktivitetsfelter, hvor børn, unge og Legeplads med mulighed for at spille basket, dyrke parkour, bane af stammer og sten, fugleredegynge, rutsjebane og voksne kan lege, optræde, spille bold og streethockey, skate klatre og hoppe på trampolin. I det hele taget et godt sted at vippende tømmerflåde. og nyde solen. lege og hænge ud. Vestvolden - ved Bystævnet (2-14 år) Lergravsparken - Lergravsvej 16 (0-16 år) Georginevej - Georginevej/Gyldenlakvej (3-10 år) På det gamle voldanlæg, formidler forskellige legestationer, Legeplads med vandleg, kæmpestort kravlenet og en sjov Legeplads indbygget i frodig byhave. Cykelbaner, trampolin, stedets militærhistorie samt de funktioner, et gammelt svævebane. Legeområde for de mindste med sandleg, baby- stammeskov, regnbuevippe og kæmpehængekøje. ’Bystævne’ havde gennem leg og bevægelse. gynger mm. Vestvolden - ved Mørkhøjvej (3-10 år) Rødegårdsparken - ved Øresundsvej 39 (0-14 år) Rødelandsvej - Vejlands Alle/Rødelandsvej (3-10 år) Legeplads med en af byens sjoveste forhindringsbaner. Legepladsen har sandkasse, klatrestammer med net, fugle- Lokal legeplads med en sandflod der slynger sig gennem Her er også fitnessredskaber, rutsjebane og anderledes gynger. redegynger, stort boldbur og ude i parken er der to borde til bakker og dale med klatreleg, stubbe, pælehuse og rutsjebane. bordfodbold. Utterslev Mose - ud for Pilesvinget 5 (3-12 år) 4 Bredegrund - Bredegrund 8 (0-16 år) Ørestad Bypark - C.F. Møllers Allé (Fra 3 år) Sørøverlegeplads på åben eng ved stien, der løber rundt om Byggelegeplads bygget af børn og voksne, legepladsen har Ørestads mange børnefamilier har fået deres første park mosen. -

Copenhagen, Denmark

Jennifer E. Wilson [email protected] www.cruisewithjenny.com 855-583-5240 | 321-837-3429 COPENHAGEN, DENMARK OVERVIEW Introduction Copenhagen, Denmark, is a city with historical charm and a contemporary style that feels effortless. It is an old merchants' town overlooking the entrance to the Baltic Sea with so many architectural treasures that it's known as the "City of Beautiful Spires." This socially progressive and tolerant metropolis manages to run efficiently yet feel relaxed. And given the Danes' highly tuned environmental awareness, Copenhagen can be enjoyed on foot or on a bicycle. Sights—Amalienborg Palace and its lovely square; Tivoli Gardens; the Little Mermaid statue; panoramic views from Rundetaarn (Round Tower); Nyhavn and its nautical atmosphere; Christiansborg Palace and the medieval ruins in the cellars. Museums—The sculptures and impressionist works at Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek; the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art and its outdoor sculpture park; paintings from the Danish Golden Age at the Hirschsprung Collection; Viking and ancient Danish artifacts at the Nationalmuseet; neoclassical sculpture at Thorvaldsens Museum. Memorable Meals—Traditional herring at Krogs Fiskerestaurant; top-notch fine dining at Geranium; Nordic-Italian fusion at Relae; traditional Danish open-face sandwiches at Schonnemanns; the best of the city's street food, all in one place, at Reffen Copenhagen Street Food. Late Night—The delightful after-dark atmosphere at Tivoli Gardens; indie rock at Loppen in Christiana; a concert at Vega. Walks—Taking in the small island of Christianshavn; walking through Dyrehaven to see herds of deer; walking from Nyhavn to Amalienborg Palace; strolling along Stroget, where the stores show off the best in Danish design. -

Copenhagen, Denmark

Your Guide to Copenhagen, Denmark Your Guide to Copenhagen at RIPE 72 – May 2016 What to See The little Mermaid At Langelinje Pier, you will find one of Copenhagen's most famous tourist attractions - the sculpture of The Little Mermaid. She turned 100-years-old on 23 August 2013. http://www.visitcopenhagen.com/copenhagen/little-mermaid-gdk586951 Christiania Christiania, the famous freetown of Copenhagen, is without a doubt one of Denmark’s most popular tourist attractions. http://www.visitcopenhagen.com/copenhagen/christiania-gdk957761 Nyhavn Nyhavn is the perfect place to end a long day, especially during summer. Have dinner at one of the cosy restaurants or do like the locals do and buy a beer from a nearby store and rest your feet by the quayside. http://www.visitcopenhagen.com/copenhagen/nyhavn-gdk474735 Strøget Strøget is one of Europe's longest pedestrian streets with a wealth of shops, from budget-friendly chains to some of the world's most expensive brands. The stretch is 1.1 km long and runs from City Hall Square (Rådhuspladsen) to Kongens Nytorv. http://www.visitcopenhagen.com/copenhagen/stroget-shopping-street-gdk414471 Lego Shop Find exclusive LEGO sets. The LEGO flagship stores are larger than average and carry a wide range of products including exclusive and difficult to find sets that are not available elsewhere. http://www.visitcopenhagen.com/copenhagen/lego-store-gdk496953 Torvehallerne Market It is not a supermarket – it is a Super Market. At Torvehallerne in Copenhagen, you will find over 60 stands selling everything from fresh fish and meat to gourmet chocolate and exotic spices, as well as small places where you can have a quick bite to eat. -

A Harbour of OPPORTUNITIES

1 A HARBOUR OF OPPORTUNITIES Visions for more activity within the Harbour of Copenhagen 2 FOREWORD – A HARBOUR OF OPPORTUNITY A GReat POtentiaL With this Vision, the City of Copenhagen wishes to spotlight the enormous pervading potential in the recreational development of the Harbour of Copen- hagen. Many new developments have taken place in the harbour in recent years, and lots of new projects are currently in progress. Even so, there is still plenty of room for many more new ideas and recreational activities. The intent of the Vision is to • inspire more activities within the harbour area • increase Copenhageners’ quality of life and health • create a stimulating abundance of cultural and recreational activities • heighten Copenhageners’ awareness of the Harbour of Copenhagen • make the city more attractive to future residents • bring together the harbour’s stakeholders to focus on jointly developing the harbour. The Harbour should be • a harbour of possibilities • a harbour for people • a harbour for everyone Thanks to the Interreg IVC-program AQUA ADD for financing of translation from Danish to English and the print of the english version. 3 COntent PURPOSE 4 AREA 5 VISION: — AN ACTIVE AND ATTRACTIVE HarBOUR 7 OWNERSHIP WITHIN THE HARBOUR AREA 8 HARBOUR USERS 10 SELECTED THEMES 13 1 — MORE ACTIVITIES WITHIN THE HarBOUR 14 2 — BETTER ACCESS TO AND FROM THE WATER 15 3 — MORE PUBLIC spaces 16 4 — BETTER ROUTES AND CONNECTIONS 17 5 — A CLEAN, INVITING HarBOUR 18 6 — A HarBOUR WITH A HEALTHY NATURAL ENVIRONMENT 19 7 — EVENTS AND TEMPORARY PROJECTS 20 8 — VARIATION AND ROOM FOR EVERYONE 21 RECOMMENDATIONS 22 PROCESS AND SCHEDULE 23 THE HARBOUR'S HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT 24 PROJECTS SITED AT THE HARBOUR 26 4 PURPOse The purpose of this Vision is to establish the framework In recent years, many of the large manufacturing industries and desire for more liveliness and activity in the Harbour of have left the harbour. -

Kasper Riewe Henriksen Set out on 8 His Own, Opening Duck and Cover, 11 After Working at Copenhagen’S Highly Regarded Cocktail Institutions

Copenhagen Kasper Riewe 5 4 Henriksen: Undercover Copenhagen Kasper Riewe Henriksen set out on 8 his own, opening Duck and Cover, 11 after working at Copenhagen’s highly regarded cocktail institutions. 10 Jul 2018 12 13 15 Kasper Riewe Henriksen 3 jauntful.com/KasperHenriksen 9 14 6 1 7 ©OpenStreetMap contributors, ©Mapbox, ©Foursquare Islands Brygge 1 The Lakes Amalienborg (Amalienborg Slot)... 3 Finn Juhls Hus 4 Neighborhood Palace Historic Site If you don’t like the sand at the beach, The Lakes are a row of three rectangular Denmark has one of the most oldest If you’re a fan of furniture design, tour you can still enjoy swimming in the inner lakes near City Centre and one of the monarchies in the world and the the home of “Danish modern” furniture harbor with the city’s skyline in view. city’s most distinctive features. Grab a changing of the guards at this Palace is designer and architect, Finn Juhl. One of cup of coffee and walk around the lakes always fun to watch. his famous pieces is the FJ45 chair. with all the locals… Copenhagen in a nutshell! Amalienborg Slotsplads, København Kratvej 15, Charlottenlund +45 33 40 10 10 45 3964 1183 ordrupgaard.dk/en/finn-juhls- kongehuset.dk/english/palaces/amalienborg house/ Louisiana Museum of Modern 5 Christiania 6 Amager Strandpark 7 BRUS 8 Art Museum Neighborhood Beach Brewery Raining? Don’t worry. Visit the museum This freetown is always worth a visit. As one of the world’s best beaches, it's This brewery offers a changing selection and treat yourself with amazing Just go and soak up the vibe! Make sure located 15 minutes by metro from City of craft beers and cocktails brewed on exhibitions and stunning architecture. -

Strøgmanual for Strøggaderne I Indre København 3

STRØGMANUAL FOR STRØGGADERNE I INDRE KØBENHAVN 3. udgave, 1. oplag 2014 © Københavns Kommune 2014 Redaktør Jens Barslund, [email protected] Foto Ursula Bach og Colourbox Layout TMF Grafisk Design Tryk GSB Grafisk Papir Cocoon 100% genbrugspapir Bogen findes også i elektronisk udgave på www.kk.dk/publikationer Københavns Kommune Teknik- og Miljøforvaltningen Njalsgade 13 2300 København S E-mail: [email protected] Telefon: +45 3366 3366 www.kk.dk INDHOLD 1 IndLedning 5 2 RestAURAtiOner 7 Udendørsservering 8 3 Butik 13 Vareudstillinger 14 Reklameskilte 16 Andre genstande 17 4 GAdeHAndeL OG OPtrÆden 19 Fast stadeplads 20 Mobilt gadesalg 23 Nyhedsformidling 27 Cykeltaxi 28 Gadeoptræden 34 Loppe- eller kræmmermarked 36 Uddeling af reklamemateriale og gratis produktsampling 36 5 Anden midLertidig brug 39 AF OffentLigt VejAreAL Stilladsreklamer 40 Bygge og anlægsmateriel 42 Stilladser 43 6 RenHOLD, CYKLer OG snerYdning 47 Renhold, cykler og snerydning 48 7 Afgifter FOR RÅden OVer VejAreAL 51 ELLer PArkAreAL 8 KOmmunens tiLSYNSPRAksis 53 RELEVAnt LOVGIVning 55 KORT OVER RØD ZONE 30 4 INDLEDNING Strøgmanualen er en hjælp til dig, der har brug for at kende reglerne for at bruge offentlige pladser og veje 1 midlertidigt, fx til skilte, vareudstillinger, udeserve- ring eller gadesalg. Du kan som forretningsdrivende, restauratør eller gadesælger bruge manualen som opslagsværk og se, hvilke regler og retningslinjer der gælder for lige netop dit område. Husk, at du altid er velkommen til at kontakte Køben- havns Kommune, hvis du er i tvivl om noget eller har brug for hjælp. FORBEHOLD Indholdet i manualen er vejledende, da Københavns Kommune i forbindelse med ledningsarbejde, vej- arbejde, byfornyelse, arrangementer og lignende har ret til at disponere over veje og pladser, selv om der er givet tilladelse til anden midlertidig brug. -

Denmark DENMARK

Denmark I.H.T. 500g of tobacco. Beer is unlimited. DENMARK Health: no precautions HOTELS●MOTELS●INNS AABENRAA SDR. HOSTRUP KRO fstergade 21 6200 AABENRAA AABENRAA DANEMARK TEL: 7461/3446 , [email protected] , http://christies.dk AARHUS RADISSON SAS SCANDINAVIA HOTEL AARHUS Margrethepladsen 1 DK-8000,Aarhus C, Denmark AARHUS DENMARK TEL: +45-86-12-86-65 FAX: +45-86-12-86-75 www.radisson.com/aarhusdk COPENHAGEN ADINA APARTMENT HOTEL COPENHAGEN, Amerika Plads 7, DK 2100 Copenhagen , Denmark, Tel: 45 3969 1000, [email protected] , http://www.adina.eu/adina-apartment-hotel-copenhagen ANDERSEN BOUTIQUE HOTEL,Helgolandsgade 12,DK-1653 København V,T: 45 33 31 46 10, [email protected] , http://www.andersen- hotel.dk/en ASCOT HOTEL Studiestræde 61 ,DK-1554 København V, Tel: 45 3312 6000, [email protected] , http://www.ascot-hotel.dk BELLA SKY COMWELL,Center Boulevard 5,2300 København S,Danmark, Tel:45 3247 3000, [email protected] , http://www.bellaskycomwell.dk BERTRAMS GULDSMEDEN COPENHAGEN, http://guldsmedenhotels.com Country Dialling Code (Tel/Fax): ++ 45 BEST WESTERN HOTEL HEBRON,Helgolandsgade 4,DK-1653 Kbh. V , Danish Tourist Board: Vesterbrogade 6 D, DK-1606 Copenhagen V, Denmark T:45 3331 6906 , [email protected] , http://www.hebron.dk Tel: 3311-1415 Fax: 3393-1416 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.dt.dk BEST WESTERN HOTEL CITY ,Peder Skrams Gade 24 ,1054 København Capital: Copenhagen Time: GMT + 1 K ,T:45 3313 0666, [email protected] , http://www.hotelcity.dk Background: Once the seat of Viking raiders and later a major north European CHARLOTTEHAVEN,Hjørringgade 12C,2100 København Ø,Tel: 45 3527 power, Denmark has evolved into a modern, prosperous nation that is participating in 1500, [email protected] ,http://www.charlottehaven.com the political and economic integration of Europe. -

ATHLETE GUIDE WELCOME to IRONMAN Copenhagen

AUGUST 22, 2021 ATHLETE GUIDE WELCOME To IRONMAN Copenhagen RACE DIRECTOR JACOB NØRGAARD Where in the world is it possible to race an IRONMAN in a capital? In Copenhagen! We are so proud to be able to organize a world class event with the IRONMAN distance in the center of a large European capital like Copenhagen for the tenth year in a row. Each IRONMAN event has its own charming and amazing aspects. In Copenhagen you get the experience of passing by some spectacular places, monuments and buildings that tourists from around the world travel to Copenhagen to see. And finally, you will be lifted by the ecstatic atmosphere from the many spectators cheering you along the courses. Of course, we cannot neglect that the last year has been incredibly challenging for all of us. Your training opportunities and preparations have not been as usual. It was extremely hard for us to cancel last year’s event and we have worked tirelessly to make sure this year's event was able to come to life, and ensure it is safe for you to compete. I hope you will contribute by complying with all covid-19 guidelines at the event and keep safe distance to others and increased level of hygiene. Despite all the modifications, I'm sure you'll still have a great experience. Over the years, the event has developed in terms of experiences from organizers, partners, but certainly as well by the feedback from the athletes. Therefore, we can hardly wait to kick off the event week with many activities that of course end up with the epic IRONMAN Copenhagen. -

CYKLERNES KØBENHAVN Det Blæser, Og Det Er Koldt

ARKITEKTUR KULTUR BYLIV DESIGN AKTIVITETER BAGGRUND Integration - På gadeplan TOP+FLOP Københavnersteder - Tobias Trier NR 10 · MAJ 2006 UPDATE Stort ved havnen - Stjernearkitekter på vej OLD SCHOOL Hovedbanegården - Fra træhytte til knudepunkt CYKLERNES KØBENHAVN Det blæser, og det er koldt. Hvad laver cyklerne i KBH? BERLIN I KBH Mensch, Fünf und Riesen. GRATIS Er København blevet tysk? HOTELSUITER 5x5 i Københavns dyreste hotelsuiter! FÅ OVERBLIK OVER HOVEDSTADENS NYE ARKITEKTUR PÅ WWW.COPENHAGENX.DK COPENHAGEN X viser vej til hovedstadens nye arkitektur med en byguide og et digitalt PROJEKTGALLERI. Se mere på www.copenhagenx.dk NY BYGUIDE 2006 UDKOMMER I MAJ ,CEFOIPT%BOTL"SLJUFLUVS$FOUFS FMMFSCFTUJMEFOIPTEJOCPHIBOEMFS Copenhagen X er en åben by- og boligudstilling (2002-2012) skabt af partnerskabet Realdania, Frederiksberg Kommune og Københavns Kommune i samarbejde med Dansk Arkitektur Center INDHOLD « DEN STORE CYKELKØBENHAVN 12 På trods af et middelmådeligt klima er København Europas cykelhovedstad. KBH fortæller cykelhistorien om byen med den store kærlighed til de tohjulede. TYSK BERLIN I KBH 32 Märkbar, Zum Biergarten og Kaiserschnitt. Berlin er cool, og tyske stednavne i København er populære som aldrig før. Hvor og hvorfor? INDRETNING HOTELSUITER 42 København har fem 5-stjernede hoteller. En nat i den bedste suite koster op mod 20.000 kroner, men hvad får man får pengene? KBH tog et kig indenfor hos alle fem. « BAGGRUND INTEGRATION 50 Rådmandsgade Skole og Nørrebro Taekwondo Klub har erfaring med integration af 12 indvandrere, og gode bud på hvordan problemerne kan løses. 28 KBHNYT 04 DEBAT 09 TING OG LIV 22 SOLBRILLER 26 OLD SCHOOL 30 HAVNEFRONTEN 37 TOP+FLOP 38 42 KØBENHAVNERE 40 « CITYTUNNEL MALMØ TRANSPORT Svenskerne giver Øresundsregionen et spark i den rigtige retning. -

Download Singer Bios

SOPRANO Susanna Andersson Her very high lyric toned soprano voice and dynamic performances have taken Susanna to important concert and opera stages worldwide. Recent and future engagements include Queen of the Night in Weimar, Wolfgang Rihm's Die Eroberung von Mexico in Salzburg Festival and Köln Opera, Violetta LA TRAVIATA in Stockholm, Pamina DIE ZAUBERFLÖTE in Turku and Queen of the Night at the Gothenburg Opera. In addition concerts all over Europe with Ingo Metzmacher conducting PROMETEO. Summer 2018 Susanna sang her favourite role Adina at the famous Swedish operafestival Opera på Skäret in Donizetti's opera L' ELISIR D' AMORE. 2018/19 brings engagements with Gustav Mahler orchestra in Berlin and concerts with orchestras in Denmark, Sweden and Finland. Sine Bundgaard Sine Bundgaard has performed extensively all over Europe and has a soloist contract with the Royal Opera in Copenhagen. She is exploring new repertoire and made her debut as Desdemona OTELLO in 2017/18. Other central roles in her current repertoire are Contessa LE NOZZE DI FIGARO, Donna Elvira DON GIOVANNI, title role in LULU, Liú in TURANDOT. She has performed with conductors like Gianandrea Noseda, Jeremie Rhorer, Michael Boder, Carlo Rizzi, Ingo Metsmacher, Rene Jacobs, Phillippe Herreweghe, Kent Nagano, Bertrand de Billy, James Conlon, Pinchas Steinberg, Michael Schønwandt, Enrique Mazzola, Matthias Pintscher, Andreas Spering, Manfred Honeck, Peter Schneider and Thomas Søndergård, Clara Cecilie Thomsen Clara Thomsen is one of the most significant Danish talents in recent years. Following her Royal Danish Opera debut in Mozart’s Le Nozze di Figaro (Barbarina) in 2017, she has appeared in the company’s production of Kuhlau’s Lulu (Second Witch) and sung the title role in the Opera Academy’s production of Handel’s Alcina at the Copenhagen Opera House. -

'Ny Amager Strandpark' / Maj 2004 / Regionplantillæg Med

Regionplantillæg med VVM Ny Amager Strandpark Maj 2004 Ny Amager Strandpark Regionplantillæg til Regionplan 2001 for Hovedstadsregionen Retningslinier og VVM-redegørelse Redaktion og grafi sk tilrettelæggelse Hovedstadens Udviklingsråd Plandivisionen Forsidefoto, Steen Lange Udgivet november 2003 af Hovedstadens Udviklingsråd Gl. Køge Landevej 3 2500 Valby Telefon 36 13 14 00 e-mail [email protected] Kort gengivet med Kort- og Matrikelstyrelsens tilladelse G13-00 Copyright Findes kun i Netudgave ISBN nr. 87-7971-115-4 Regionplantillæg til Regionplan 2001 for Hovedstadsregionen Retningslinier og VVM-redegørelse Ny Amager Strandpark Maj 2004 Indholdsfortegnelse Forord......................................................................................................................... 5 Læsevejledning Efter retningslinierne og en rede- 1. Indledning ..............................................................................................................6 gørelse for de planmæssige for- hold, er der i kapitel 4 et kortfattet 2. Retningslinier ........................................................................................................ 8 ikke-teknisk resumé af VVM-rede- gørelsen. Sidst i dette kapitel er 3. Redegørelse............................................................................................................11 HURs sammenfattende vurdering af miljøkonsekvenserne ved etable- 4. Resumé ................................................................................................................. 13 ring af den nye -

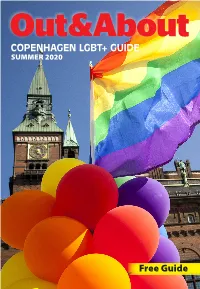

COPENHAGEN LGBT+ GUIDE Free Guide

COPENHAGEN LGBT+ GUIDE SUMMER 2020 Free Guide Out&About Copenhagen LGBT+ Guide * Summer 2020 1 Welcome to Copenhagen A city with room for diversity Copenhagen is a vibrant, liveable city Since the very first homosexual with a colourful cultural life. We have marriage in Copenhagen in 1989, our highly developed public transporta- city has been a pioneer in the field of tion, a bicycle infrastructure second LGBTI+ rights. In 2019 we adopted a to none and our harbour is so clean, new overall LGBTI+ policy to ensure that you can swim in it. For those – that the municipality meets LGBTI+ and many other reasons – Copen- persons with respect, equality, dia- hagen is continuously rated among logue and confidence. This makes the most liveable cities in the world. Copenhagen the first Danish mu- Another vital reason for our live- nicipality with an overall policy in ability is Copenhagen’s famous this area. open-mindedness and tolerance. In Copenhagen, we are very proud No matter your colour, sexual orien- of the city’s social diversity and tol- tation, religion or gender identity, erance. And we actively protect and Copenhagen welcomes you. promote the freedom of expression 2020 has been a very exceptional for all minority groups. year worldwide including Denmark As Denmark slowly begins to open and Copenhagen due to the Covid-19 the borders after the corona lock pandemic. I look forward to getting down, we look forward to welcom- our city back to its usual vibrant self ing visitors from all over the world with both local and international yet again.