Nicotine Stimulates PPARB/D Expression in Human Lung Carcinoma Cells Through Activation of PI3K/Mtor and Suppression of AP-2A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Animal Model with a Cardiomyocyte-Specific Deletion of Estrogen Receptor Alpha: Functional, Metabolic, and Differential Netwo

Washington University School of Medicine Digital Commons@Becker Open Access Publications 2014 An animal model with a cardiomyocyte-specific deletion of estrogen receptor alpha: Functional, metabolic, and differential network analysis Sriram Devanathan Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis Timothy Whitehead Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis George G. Schweitzer Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis Nicole Fettig Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis Attila Kovacs Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/open_access_pubs Recommended Citation Devanathan, Sriram; Whitehead, Timothy; Schweitzer, George G.; Fettig, Nicole; Kovacs, Attila; Korach, Kenneth S.; Finck, Brian N.; and Shoghi, Kooresh I., ,"An animal model with a cardiomyocyte-specific deletion of estrogen receptor alpha: Functional, metabolic, and differential network analysis." PLoS One.9,7. e101900. (2014). https://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/open_access_pubs/3326 This Open Access Publication is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Becker. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Becker. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Sriram Devanathan, Timothy Whitehead, George G. Schweitzer, Nicole Fettig, Attila Kovacs, Kenneth S. Korach, Brian N. Finck, and Kooresh I. Shoghi This open access publication is available at Digital Commons@Becker: https://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/open_access_pubs/3326 An Animal Model with a Cardiomyocyte-Specific Deletion of Estrogen Receptor Alpha: Functional, Metabolic, and Differential Network Analysis Sriram Devanathan1, Timothy Whitehead1, George G. Schweitzer2, Nicole Fettig1, Attila Kovacs3, Kenneth S. -

NATURAL KILLER CELLS, HYPOXIA, and EPIGENETIC REGULATION of HEMOCHORIAL PLACENTATION by Damayanti Chakraborty Submitted to the G

NATURAL KILLER CELLS, HYPOXIA, AND EPIGENETIC REGULATION OF HEMOCHORIAL PLACENTATION BY Damayanti Chakraborty Submitted to the graduate degree program in Pathology and Laboratory Medicine and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chair: Michael J. Soares, Ph.D. ________________________________ Jay Vivian, Ph.D. ________________________________ Patrick Fields, Ph.D. ________________________________ Soumen Paul, Ph.D. ________________________________ Michael Wolfe, Ph.D. ________________________________ Adam J. Krieg, Ph.D. Date Defended: 04/01/2013 The Dissertation Committee for Damayanti Chakraborty certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: NATURAL KILLER CELLS, HYPOXIA, AND EPIGENETIC REGULATION OF HEMOCHORIAL PLACENTATION ________________________________ Chair: Michael J. Soares, Ph.D. Date approved: 04/01/2013 ii ABSTRACT During the establishment of pregnancy, uterine stromal cells differentiate into decidual cells and recruit natural killer (NK) cells. These NK cells are characterized by low cytotoxicity and distinct cytokine production. In rodent as well as in human pregnancy, the uterine NK cells peak in number around mid-gestation after which they decline. NK cells associate with uterine spiral arteries and are implicated in pregnancy associated vascular remodeling processes and potentially in modulating trophoblast invasion. Failure of trophoblast invasion and vascular remodeling has been shown to be associated with pathological conditions like preeclampsia syndrome, hypertension in mother and/or fetal growth restriction. We hypothesize that NK cells fundamentally contribute to the organization of the placentation site. In order to study the in vivo role of NK cells during pregnancy, gestation stage- specific NK cell depletion was performed in rats using anti asialo GM1 antibodies. -

140503 IPF Signatures Supplement Withfigs Thorax

Supplementary material for Heterogeneous gene expression signatures correspond to distinct lung pathologies and biomarkers of disease severity in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis Daryle J. DePianto1*, Sanjay Chandriani1⌘*, Alexander R. Abbas1, Guiquan Jia1, Elsa N. N’Diaye1, Patrick Caplazi1, Steven E. Kauder1, Sabyasachi Biswas1, Satyajit K. Karnik1#, Connie Ha1, Zora Modrusan1, Michael A. Matthay2, Jasleen Kukreja3, Harold R. Collard2, Jackson G. Egen1, Paul J. Wolters2§, and Joseph R. Arron1§ 1Genentech Research and Early Development, South San Francisco, CA 2Department of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, CA 3Department of Surgery, University of California, San Francisco, CA ⌘Current address: Novartis Institutes for Biomedical Research, Emeryville, CA. #Current address: Gilead Sciences, Foster City, CA. *DJD and SC contributed equally to this manuscript §PJW and JRA co-directed this project Address correspondence to Paul J. Wolters, MD University of California, San Francisco Department of Medicine Box 0111 San Francisco, CA 94143-0111 [email protected] or Joseph R. Arron, MD, PhD Genentech, Inc. MS 231C 1 DNA Way South San Francisco, CA 94080 [email protected] 1 METHODS Human lung tissue samples Tissues were obtained at UCSF from clinical samples from IPF patients at the time of biopsy or lung transplantation. All patients were seen at UCSF and the diagnosis of IPF was established through multidisciplinary review of clinical, radiological, and pathological data according to criteria established by the consensus classification of the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and European Respiratory Society (ERS), Japanese Respiratory Society (JRS), and the Latin American Thoracic Association (ALAT) (ref. 5 in main text). Non-diseased normal lung tissues were procured from lungs not used by the Northern California Transplant Donor Network. -

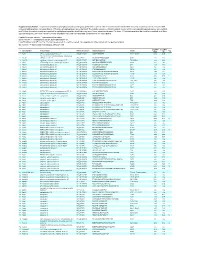

Supplementary Table 1

Supplementary Table 1. Large-scale quantitative phosphoproteomic profiling was performed on paired vehicle- and hormone-treated mTAL-enriched suspensions (n=3). A total of 654 unique phosphopeptides corresponding to 374 unique phosphoproteins were identified. The peptide sequence, phosphorylation site(s), and the corresponding protein name, gene symbol, and RefSeq Accession number are reported for each phosphopeptide identified in any one of three experimental pairs. For those 414 phosphopeptides that could be quantified in all three experimental pairs, the mean Hormone:Vehicle abundance ratio and corresponding standard error are also reported. Peptide Sequence column: * = phosphorylated residue Site(s) column: ^ = ambiguously assigned phosphorylation site Log2(H/V) Mean and SE columns: H = hormone-treated, V = vehicle-treated, n/a = peptide not observable in all 3 experimental pairs Sig. column: * = significantly changed Log 2(H/V), p<0.05 Log (H/V) Log (H/V) # Gene Symbol Protein Name Refseq Accession Peptide Sequence Site(s) 2 2 Sig. Mean SE 1 Aak1 AP2-associated protein kinase 1 NP_001166921 VGSLT*PPSS*PK T622^, S626^ 0.24 0.95 PREDICTED: ATP-binding cassette, sub-family A 2 Abca12 (ABC1), member 12 XP_237242 GLVQVLS*FFSQVQQQR S251^ 1.24 2.13 3 Abcc10 multidrug resistance-associated protein 7 NP_001101671 LMT*ELLS*GIRVLK T464, S468 -2.68 2.48 4 Abcf1 ATP-binding cassette sub-family F member 1 NP_001103353 QLSVPAS*DEEDEVPVPVPR S109 n/a n/a 5 Ablim1 actin-binding LIM protein 1 NP_001037859 PGSSIPGS*PGHTIYAK S51 -3.55 1.81 6 Ablim1 actin-binding -

Application of Microrna Database Mining in Biomarker Discovery and Identification of Therapeutic Targets for Complex Disease

Article Application of microRNA Database Mining in Biomarker Discovery and Identification of Therapeutic Targets for Complex Disease Jennifer L. Major, Rushita A. Bagchi * and Julie Pires da Silva * Department of Medicine, Division of Cardiology, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO 80045, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (R.A.B.); [email protected] (J.P.d.S.) Supplementary Tables Methods Protoc. 2021, 4, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps4010005 www.mdpi.com/journal/mps Methods Protoc. 2021, 4, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps4010005 2 of 25 Table 1. List of all hsa-miRs identified by Human microRNA Disease Database (HMDD; v3.2) analysis. hsa-miRs were identified using the term “genetics” and “circulating” as input in HMDD. Targets CAD hsa-miR-1 Targets IR injury hsa-miR-423 Targets Obesity hsa-miR-499 hsa-miR-146a Circulating Obesity Genetics CAD hsa-miR-423 hsa-miR-146a Circulating CAD hsa-miR-149 hsa-miR-499 Circulating IR Injury hsa-miR-146a Circulating Obesity hsa-miR-122 Genetics Stroke Circulating CAD hsa-miR-122 Circulating Stroke hsa-miR-122 Genetics Obesity Circulating Stroke hsa-miR-26b hsa-miR-17 hsa-miR-223 Targets CAD hsa-miR-340 hsa-miR-34a hsa-miR-92a hsa-miR-126 Circulating Obesity Targets IR injury hsa-miR-21 hsa-miR-423 hsa-miR-126 hsa-miR-143 Targets Obesity hsa-miR-21 hsa-miR-223 hsa-miR-34a hsa-miR-17 Targets CAD hsa-miR-223 hsa-miR-92a hsa-miR-126 Targets IR injury hsa-miR-155 hsa-miR-21 Circulating CAD hsa-miR-126 hsa-miR-145 hsa-miR-21 Targets Obesity hsa-mir-223 hsa-mir-499 hsa-mir-574 Targets IR injury hsa-mir-21 Circulating IR injury Targets Obesity hsa-mir-21 Targets CAD hsa-mir-22 hsa-mir-133a Targets IR injury hsa-mir-155 hsa-mir-21 Circulating Stroke hsa-mir-145 hsa-mir-146b Targets Obesity hsa-mir-21 hsa-mir-29b Methods Protoc. -

Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell–Derived Podocytes Mature Into Vascularized Glomeruli Upon Experimental Transplantation

BASIC RESEARCH www.jasn.org Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell–Derived Podocytes Mature into Vascularized Glomeruli upon Experimental Transplantation † Sazia Sharmin,* Atsuhiro Taguchi,* Yusuke Kaku,* Yasuhiro Yoshimura,* Tomoko Ohmori,* ‡ † ‡ Tetsushi Sakuma, Masashi Mukoyama, Takashi Yamamoto, Hidetake Kurihara,§ and | Ryuichi Nishinakamura* *Department of Kidney Development, Institute of Molecular Embryology and Genetics, and †Department of Nephrology, Faculty of Life Sciences, Kumamoto University, Kumamoto, Japan; ‡Department of Mathematical and Life Sciences, Graduate School of Science, Hiroshima University, Hiroshima, Japan; §Division of Anatomy, Juntendo University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan; and |Japan Science and Technology Agency, CREST, Kumamoto, Japan ABSTRACT Glomerular podocytes express proteins, such as nephrin, that constitute the slit diaphragm, thereby contributing to the filtration process in the kidney. Glomerular development has been analyzed mainly in mice, whereas analysis of human kidney development has been minimal because of limited access to embryonic kidneys. We previously reported the induction of three-dimensional primordial glomeruli from human induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells. Here, using transcription activator–like effector nuclease-mediated homologous recombination, we generated human iPS cell lines that express green fluorescent protein (GFP) in the NPHS1 locus, which encodes nephrin, and we show that GFP expression facilitated accurate visualization of nephrin-positive podocyte formation in -

For Personal Use. Only Reproduce with Permission from the Lancet

Correlation to non-HGNT Accesion group 2 Description AA897204 1.479917 ESTs T85111 1.286576 null T60168 | AI821353 1.274487 thyroid transcription factor 1 AA600173 1.183065 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2A (RAD6 homolog) R55745 1.169339 ELAV (embryonic lethal, abnormal vision, Drosophila)-like 4 (Hu antigen D) AA400492 1.114935 ESTs AA864791 1.088826 hypothetical protein FLJ21313 N53758 1.070402 EST AI216628 1.067763 ESTs AI167637 1.058561 ESTs AA478265 1.056331 similar to transmembrane receptor Unc5H1 AA969924 1.039315 EST AI074650 1.039043 hypothetical protein FLJ13842 R20763 1.035807 ELAV (embryonic lethal, abnormal vision, Drosophila)-like 3 (Hu antigen C) AI347081 1.034518 Ca2+-dependent activator protein for secretion R44386 1.028005 ESTs AA976699 1.027227 chromogranin A (parathyroid secretory protein 1) AA634475 1.026766 KIAA1796 protein AA496809 1.02432 SWI/SNF related, matrix associated, actin dependent regulator of chromatin, subfamily a, member 1 H16572 1.013059 null H29013 1.002117 seizure related 6 homolog (mouse)-like AI299731 1.001053 Homo sapiens nanos mRNA, partial cds AA400194 0.9950039 EST AI216537 | AI820870 0.9737153 Homo sapiens cDNA FLJ39674 fis, clone SMINT2009505 AA426408 0.9728649 type I transmembrane receptor (seizure-related protein) AA971742 | AI733380 0.9707561 achaete-scute complex-like 1 (Drosophila) R41450 0.9655133 ESTs AA487505 0.9636143 immunoglobulin superfamily, member 4 AA404337 0.957686 thymus high mobility group box protein TOX N68578 0.9552571 ESTs R45008 0.9422938 ELAV (embryonic lethal, abnormal -

FACTORIAL™ Screening Services

FactorialTM Biosensors for Drug Discovery and Toxicology Attagene offers functional characterization of compounds according to their effect on regulatory and toxicity pathways of mammalian cells. Our services utilize patented multiplex profiling technology termed FactorialTM. Principle Activity of transcription factors (TF) is regulated by multiple mechanisms such as phosphorylation, nuclear translocation, ligand binding or co-factor recruitment. To directly measure pathways regulating TF activity, Attagene has developed a novel pathway profiling technology, FactorialTM enabling multiplex assessment of hundreds of reporters in a single tissue-culture well. FactorialTM assay utilizes an unique library of TF-specific reporters. All reporters are analyzed in a single reaction well followed by quantitative analysis using capillary electrophoresis (1). Major advantages of FactorialTM technology over conventional pathway profiling assays • Multiplexing: FactorialTM analyses more than 40 pathways in a single assay well. The endpoint set is easily expandable and customizable. Relatively small quantities of compound are needed for the assay. • High uniformity. All FactorialTM reporters produce virtually identical RNA messages with no detectable variability in stability of individual reporter RNA enabling precise comparison of the activities of multiple TFs. • Fast detection of TF activity changes. FactorialTM detection is performed on the mRNA level, therefore FactorialTM reporters react faster than conventional protein- based reporters to both -

The Genetic Program of Pancreatic Beta-Cell Replication in Vivo

Page 1 of 65 Diabetes The genetic program of pancreatic beta-cell replication in vivo Agnes Klochendler1, Inbal Caspi2, Noa Corem1, Maya Moran3, Oriel Friedlich1, Sharona Elgavish4, Yuval Nevo4, Aharon Helman1, Benjamin Glaser5, Amir Eden3, Shalev Itzkovitz2, Yuval Dor1,* 1Department of Developmental Biology and Cancer Research, The Institute for Medical Research Israel-Canada, The Hebrew University-Hadassah Medical School, Jerusalem 91120, Israel 2Department of Molecular Cell Biology, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel. 3Department of Cell and Developmental Biology, The Silberman Institute of Life Sciences, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem 91904, Israel 4Info-CORE, Bioinformatics Unit of the I-CORE Computation Center, The Hebrew University and Hadassah, The Institute for Medical Research Israel- Canada, The Hebrew University-Hadassah Medical School, Jerusalem 91120, Israel 5Endocrinology and Metabolism Service, Department of Internal Medicine, Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center, Jerusalem 91120, Israel *Correspondence: [email protected] Running title: The genetic program of pancreatic β-cell replication 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online March 18, 2016 Diabetes Page 2 of 65 Abstract The molecular program underlying infrequent replication of pancreatic beta- cells remains largely inaccessible. Using transgenic mice expressing GFP in cycling cells we sorted live, replicating beta-cells and determined their transcriptome. Replicating beta-cells upregulate hundreds of proliferation- related genes, along with many novel putative cell cycle components. Strikingly, genes involved in beta-cell functions, namely glucose sensing and insulin secretion were repressed. Further studies using single molecule RNA in situ hybridization revealed that in fact, replicating beta-cells double the amount of RNA for most genes, but this upregulation excludes genes involved in beta-cell function. -

Supplementary Tables S1-S3

Supplementary Table S1: Real time RT-PCR primers COX-2 Forward 5’- CCACTTCAAGGGAGTCTGGA -3’ Reverse 5’- AAGGGCCCTGGTGTAGTAGG -3’ Wnt5a Forward 5’- TGAATAACCCTGTTCAGATGTCA -3’ Reverse 5’- TGTACTGCATGTGGTCCTGA -3’ Spp1 Forward 5'- GACCCATCTCAGAAGCAGAA -3' Reverse 5'- TTCGTCAGATTCATCCGAGT -3' CUGBP2 Forward 5’- ATGCAACAGCTCAACACTGC -3’ Reverse 5’- CAGCGTTGCCAGATTCTGTA -3’ Supplementary Table S2: Genes synergistically regulated by oncogenic Ras and TGF-β AU-rich probe_id Gene Name Gene Symbol element Fold change RasV12 + TGF-β RasV12 TGF-β 1368519_at serine (or cysteine) peptidase inhibitor, clade E, member 1 Serpine1 ARE 42.22 5.53 75.28 1373000_at sushi-repeat-containing protein, X-linked 2 (predicted) Srpx2 19.24 25.59 73.63 1383486_at Transcribed locus --- ARE 5.93 27.94 52.85 1367581_a_at secreted phosphoprotein 1 Spp1 2.46 19.28 49.76 1368359_a_at VGF nerve growth factor inducible Vgf 3.11 4.61 48.10 1392618_at Transcribed locus --- ARE 3.48 24.30 45.76 1398302_at prolactin-like protein F Prlpf ARE 1.39 3.29 45.23 1392264_s_at serine (or cysteine) peptidase inhibitor, clade E, member 1 Serpine1 ARE 24.92 3.67 40.09 1391022_at laminin, beta 3 Lamb3 2.13 3.31 38.15 1384605_at Transcribed locus --- 2.94 14.57 37.91 1367973_at chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 Ccl2 ARE 5.47 17.28 37.90 1369249_at progressive ankylosis homolog (mouse) Ank ARE 3.12 8.33 33.58 1398479_at ryanodine receptor 3 Ryr3 ARE 1.42 9.28 29.65 1371194_at tumor necrosis factor alpha induced protein 6 Tnfaip6 ARE 2.95 7.90 29.24 1386344_at Progressive ankylosis homolog (mouse) -

Functional Characterization of the Basal Promoter of the Murine LH Receptor Gene in Immortalized Mouse Leydig Tumor Cells

21 Functional characterization of the basal promoter of the murine LH receptor gene in immortalized mouse Leydig tumor cells H Nikula1, P Koskimies1,2, T El-Hefnawy1 and I Huhtaniemi1 1Department of Physiology, University of Turku, Kiinamyllynkatu 10, FIN-20520 Turku, Finland 2Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, University of Turku, Kiinamyllynkatu 10, FIN-20520 Turku, Finland (Requests for offprints should be addressed to I Huhtaniemi; Email: ilpo.huhtaniemi@utu.fi) ABSTRACT The nuclear proteins of the LH receptor (LHR) specificity for Sp1. Partly similar, though weaker, expressing murine Leydig tumor cells (mLTC-1), complexes were seen with HeLa cell extracts. The binding to the LHR primary promoter, were most clearcut differences between the protein/DNA studied by gel retardation assays. Nuclear extracts complexes formed with LHR expressing mLTC-1 of HeLa cells, not expressing LHR, were used as cells and non-expressing (HeLa, COS, HEK 293 control. Protein binding was characterized to the and MSC-1) cells were found with fragment I. first 173 base pairs (bp) of the LHR 5-untranslated Extracts of the non-expressing cells formed one region, comprising the basal transcriptional pro- prominent protein/DNA complex which was miss- moter activity in mLTC-1 cells, and accounting for ing in mLTC-1 cells. Purified Sp1 also bound to the Leydig cell-specific LHR expression. The this fragment. The fragment containing the putative promoter fragment is GC-rich and contains several SF-1 binding site did not form any protein/DNA Sp1 sites, one activating protein 2 (AP-2) site, and a complexes with mLTC-1 cell proteins. -

Oligodendrocytes Remodel the Genomic Fabrics of Functional Pathways in Astrocytes

1 Article 2 Oligodendrocytes remodel the genomic fabrics of 3 functional pathways in astrocytes 4 Dumitru A Iacobas 1,2,*, Sanda Iacobas 3, Randy F Stout 4 and David C Spray 2,5 5 Supplementary Material 6 Table S1. Genes whose >1.5x absolute fold-change did not meet the individual CUT criterion. 7 Red/green background of the expression ratio indicates not significant (false) up-/down-regulation. Gene Description X CUT Acap2 ArfGAP with coiled-coil, ankyrin repeat and PH domains 2 -1.540 1.816 Adamts18 a disintegrin-like and metallopeptidase -1.514 1.594 Akr1c12 aldo-keto reductase family 1, member C12 1.866 1.994 Alx3 aristaless-like homeobox 3 1.536 1.769 Alyref2 Aly/REF export factor 2 -1.880 2.208 Ankrd33b ankyrin repeat domain 33B 1.593 1.829 Ankrd45 ankyrin repeat domain 45 1.514 1.984 Ankrd50 ankyrin repeat domain 50 1.628 1.832 Ankrd61 ankyrin repeat domain 61 1.645 1.802 Arid1a AT rich interactive domain 1A -1.668 2.066 Artn artemin 1.524 1.732 Aspm abnormal spindle microtubule assembly -1.693 1.716 Atp6v1e1 ATPase, H+ transporting, lysosomal V1 subunit E1 -1.679 1.777 Bag4 BCL2-associated athanogene 4 1.723 1.914 Birc3 baculoviral IAP repeat-containing 3 -1.588 1.722 Ccdc104 coiled-coil domain containing 104 -1.819 2.130 Ccl2 chemokine -1.699 2.034 Cdc20b cell division cycle 20 homolog B 1.512 1.605 Cenpf centromere protein F 2.041 2.128 Cep97 centrosomal protein 97 -1.641 1.723 COX1 mitochondrially encoded cytochrome c oxidase I -1.607 1.650 Cpsf7 cleavage and polyadenylation specific factor 7 -1.635 1.891 Crct1 cysteine-rich