Final Copy 2021 05 11 Amor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HARD FACTS and SOFT SPECULATION Thierry De Duve

THE STORY OF FOUNTAIN: HARD FACTS AND SOFT SPECULATION Thierry de Duve ABSTRACT Thierry de Duve’s essay is anchored to the one and perhaps only hard fact that we possess regarding the story of Fountain: its photo in The Blind Man No. 2, triply captioned “Fountain by R. Mutt,” “Photograph by Alfred Stieglitz,” and “THE EXHIBIT REFUSED BY THE INDEPENDENTS,” and the editorial on the facing page, titled “The Richard Mutt Case.” He examines what kind of agency is involved in that triple “by,” and revisits Duchamp’s intentions and motivations when he created the fictitious R. Mutt, manipulated Stieglitz, and set a trap to the Independents. De Duve concludes with an invitation to art historians to abandon the “by” questions (attribution, etc.) and to focus on the “from” questions that arise when Fountain is not seen as a work of art so much as the bearer of the news that the art world has radically changed. KEYWORDS, Readymade, Fountain, Independents, Stieglitz, Sanitary pottery Then the smell of wet glue! Mentally I was not spelling art with a capital A. — Beatrice Wood1 No doubt, Marcel Duchamp’s best known and most controversial readymade is a men’s urinal tipped on its side, signed R. Mutt, dated 1917, and titled Fountain. The 2017 centennial of Fountain brought us a harvest of new books and articles on the famous or infamous urinal. I read most of them in the hope of gleaning enough newly verified facts to curtail my natural tendency to speculate. But newly verified facts are few and far between. -

Film, Folders, and Mina Loy

FORUM: IN THE ARCHIVES Live from the Archive: Film, Folders, and Mina Loy Sasha Colby In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, much of the talk around ideas of re-animation centred on the great archaeological expeditions where place names stood for sites of unimaginable recovery: Egypt, Mesopotamia, Greece, Pompeii. A body of literature arose around this reclamation, often imaginatively reconstituting the historical from its material remains. The unprecedented unearthing of the past also led to questions: how could material relics at once be past yet at the same time exist in the present; give rise to fantasies of reconnection; disorient the line between then and now? Writers from Pater to Nietzsche were preoccupied by these questions and also by the perceived dangers of being consumed by history—as well as the delusion of being able to reclaim it. Intriguingly, in our own moment, new versions of these debates have been taken up by Performance Studies scholars, on many counts an unlikely group of inheritors. Yet questions about the power of the object in the archive, its ability to summon the past, its place in the present, its relation to performance modalities, and the archiving of performance itself, in many ways bear the traces of these earlier discussions. Indeed, Mike Pearson and Michael Shanks’ Theatre/Archaeology (2001) situates itself at this border precisely in order to unpack the conceptual similarities of theatrical and archaeological projects, all of which gesture, as Rebecca Schneider (2011) has shown, to reenactment as a kind of end-point for rediscovery. When I put away my first book, Stratified Modernism (2009), about the relationship between archaeology and modernist writing, in order to start the second, Staging Modernist Lives, I thought—as we so often do—that I was putting one thing aside in order to start something entirely new: in this case, a treatise on the usefulness of biographical performance for modernist scholarship that includes three of my own plays about writers H. -

How Women Wrote Modernism, 1900 to 1940 Course Number Spanish M98T Multiple Listed with Gender Studies M98T

Spanish/Gender Studies M98T General Education Course Information Sheet Please submit this sheet for each proposed course SPA/M 98T (Please cross list Spanish and Portuguese & Department & Course Number Women’s Studies, * Comp Lit as well if possible*) “Her Side of the Story: How Women ‘Wrote’ Course Title Modernism(1900-1940) 1 Check the recommended GE foundation area(s) and subgroups(s) for this course Foundations of the Arts and Humanities Literary and Cultural Analysis X Philosophic and Linguistic Analysis Visual and Performance Arts Analysis and Practice Foundations of Society and Culture Historical Analysis Social Analysis Foundations of Scientific Inquiry Physical Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) Life Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) 2. Briefly describe the rationale for assignment to foundation area(s) and subgroup(s) chosen. This course will help students: Understand the socio-historic conditions that led to the development of Modernist movements. Study canonical Modernist texts. Learn to distinguish fundamental aesthetic characteristics of early twentieth century Modernisms through the study of prose, poetry and visual arts. (using primary and secondary sources). Explore the close relationship between Modernist movements and women’s changing social roles in the early twentieth century. Illustrate women’s importance as agents of transnational and transatlantic Modernist movements. Critically engage texts and develop research and writing skills. 3. List faculty member(s) and teaching fellow who will serve as instructor (give academic rank): Professor Roberta Johnson Visiting Professor, UCLA Department of Spanish and Portuguese/ Professor Emerita, University of Kansas 4. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Fillia's Futurism Writing

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Fillia’s Futurism Writing, Politics, Gender and Art after the First World War A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Italian By Adriana Marie Baranello 2014 © Copyright by Adriana Marie Baranello 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Fillia’s Futurism Writing, Politics, Gender and Art after the First World War By Adriana Marie Baranello Doctor of Philosophy in Italian University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Lucia Re, Co-Chair Professor Claudio Fogu, Co-Chair Fillia (Luigi Colombo, 1904-1936) is one of the most significant and intriguing protagonists of the Italian futurist avant-garde in the period between the two World Wars, though his body of work has yet to be considered in any depth. My dissertation uses a variety of critical methods (socio-political, historical, philological, narratological and feminist), along with the stylistic analysis and close reading of individual works, to study and assess the importance of Fillia’s literature, theater, art, political activism, and beyond. Far from being derivative and reactionary in form and content, as interwar futurism has often been characterized, Fillia’s works deploy subtler, but no less innovative forms of experimentation. For most of his brief but highly productive life, Fillia lived and worked in Turin, where in the early 1920s he came into contact with Antonio Gramsci and his factory councils. This led to a period of extreme left-wing communist-futurism. In the mid-1920s, following Marinetti’s lead, Fillia moved toward accommodation with the fascist regime. This shift to the right eventually even led to a phase ii dominated by Catholic mysticism, from which emerged his idiosyncratic and highly original futurist sacred art. -

A History of Modernist Poetry Edited by Alex Davis and Lee M

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-03867-7 - A History of Modernist Poetry Edited by Alex Davis and Lee M. Jenkins Frontmatter More information A HISTORY OF MODERNIST POETRY A History of Modernist Poetry examines innovative anglophone poetries from decadence to the post-war period. The first of its three parts considers formal and contextual issues, including myth, politics, gender, and race, while the second and third parts discuss a wide range of individual poets, including Ezra Pound, T. S. Eliot, W. B. Yeats, Mina Loy, Gertrude Stein, Wallace Stevens, William Carlos Williams, and Marianne Moore, as well as key movements such as Imagism, Objectivism, and the Harlem Renaissance. This book also addresses the impact of both world wars on experimental poetries and the crucial role of magazines in disseminating and proselytising on behalf of poetic modernism. The collection con- cludes with a wide-ranging discussion of the inheritance of mod- ernism in recent writing on both sides of the Atlantic. alex davis is Professor of English at University College Cork, Ireland. He is the author of A Broken Line: Denis Devlin and Irish Poetic Modernism (2000) and many essays on anglophone poetry from decadence to the present day. He is co-editor, with Lee M. Jenkins, of Locations of Literary Modernism: Region and Nation in British and American Modernist Poetry (2000)andThe Cambridge Companion to Modernist Poetry (2007) and, with Patricia Coughlan, of Modernism and Ireland: The Poetry of the 1930s (1995). lee m. jenkins is Senior Lecturer in English at University College Cork, Ireland. She is the author of Wallace Stevens: Rage for Order (1999), The Language of Caribbean Poetry: Boundaries of Expression (2004), and The American Lawrence (2015). -

The Great and the Small

PREFACE The Great and the Small “How very beautiful these gems are!” said Dorothea, under a new current of feeling, as sudden as the gleam. “It is strange how deeply colours seem to penetrate one, like scent. I suppose this is the reason why gems are used as spiritual emblems in the Revelation of St John. They look like fragments of heaven.” George Eliot, Middlemarch: A Study of Provincial Life I remember� the first time I encountered Joseph Cornell. It was 2004, a few months into my sophomore year of college, and the Museum of Modern Art had just reopened in a gleaming building on Fifty- Third Street. Ascending the ziggurat of escalators to the fifth floor, I wandered past paintings by Cézanne, Picasso, and Matisse before arriving at the gallery dedicated to Surrealism. Cornell’s Taglioni’s Jewel Casket from 1940 was installed in the corner of a large plexiglass vitrine (figs. P.1, P.2). Just twelve inches wide, this modest box holds a world. Glass cubes shine like diamonds, like the paste necklace draped across the box’s lid, whose rhinestones form an arc of sparkle below a block of blue text. This text tells the tale of the famed nineteenth-century ballet dancer Marie Taglioni (fig. P.3). While traveling on a Russian highway one snowy night in 1835, Taglioni’s carriage was stopped by a bandit. Unfurling a panther’s skin on the icy ground, she proceeded to dance so beautifully that the robber allowed her to leave unmolested, her jewels still in her possession. -

Modernist Paris: Artists and Intellectuals Subject Area/Course Number: Humanities 30

Course Outline of Record Los Medanos College 2700 East Leland Road Pittsburg CA 94565 Course Title: Modernist Paris: Artists and Intellectuals Subject Area/Course Number: Humanities 30 New Course OR Existing Course Author(s): Mariel Morison, Jennifer Saito Subject Area/Course No.: HUMAN-030 Units: 3 Course Title: Modernist Paris: Artists & Intellectuals Discipline(s): Humanities, Art, Drama, Music, English, Philosophy, History Pre-Requisite(s): None Co-Requisite(s): Advisories: Eligibility for ENGL-100 Catalog Description: An integrated interdisciplinary approach to intellectual and cultural history, using the products of Modernism—philosophy, literature, art, music, dance and film, and focusing on Paris as a nexus of creative thought in the period from the mid-19th century through the mid-20th. In this broad context, students will investigate the intellectual, artistic and philosophical foundations of Modernism in Western culture. Schedule Description: Pablo Picasso. Gertrude Stein. Ernest Hemingway. Isadora Duncan. What do they have in common? All these artists and intellectuals converged on Paris in the early 20th century to contribute to Modernism, a radical, wide-reaching movement. Its ideas and aesthetics forever shifted the trajectory of art and still linger today. Whether it was through poetry, fiction, music, theater, film, dance, philosophy, photography, or painting, the Modernist’s quest for heresy and self-scrutiny shook foundations and changed culture. While Modernism developed in many locations, Paris in particular was the -

“Face of the Skies”: Ekphrastic Poetics of Mina Loy's Late Poems

“Face of the skies”: Ekphrastic Poetics of Mina Loy’s Late Poems Raphael Schulte After a lifetime engaged in “migratory modernism,” to quote a term from Rachel Blau DuPlessis (191), the seventy-year old painter and poet Mina Loy (1882-1966) moved in 1953 to Aspen, Colorado, a town with only about nine hundred residents. Loy, who had participated in most of the major art movements of the first half of the twentieth century—Symbolism, Cubism, Futurism, Dadaism, and Surrealism—and had lived in London, Paris, Vienna, Munich, Berlin, Florence, Geneva, Buenos Aires, Mexico City, Rio de Janiero and New York City, moved to the artistic backwater world of 1950s Aspen in order to be with her daughters Joella and Fabienne and their families. The move proved to be both isolating and stimulating. In a September 26,1955 letter to the artist Joseph Cornell, one of her friends in New York City, Loy wrote: It’s nearly two years since they whisked me up here. I am not at my ease here, but the altitude is stimulating—sometimes surprising. When I arrived my hair stood on end and crackled with electricity, the metal utilities give electric shocks under one’s fingernails—the Radio is a volley of shots except at night— & in the streets mostly all there is to walk on are 3 cornered stones” (qtd in Burke Becoming 427).1 In this new life of isolation from her friends but stimulation from the “electricity” in the mountain air, Loy looked both backward and forward. Within a year of her arrival in Aspen, in July 1954, Loy completed, probably by memory, a pencil portrait of Teri Fraenkel.2 Teri may have seemed like an unlikely choice for a portrait. -

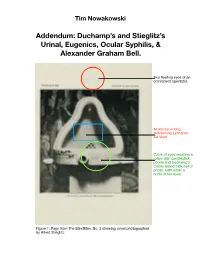

Addendum- Duchamp's and Stieglitz's Urinal, Eugenics, Ocular Syphilis

Tim Nowakowski Addendum: Duchamp’s and Stieglitz’s Urinal, Eugenics, Ocular Syphilis, & Alexander Graham Bell. Two floating eyes of an omniscient spectator. Mirrorical writing referencing Leonardo Da Vinci. Circle of eyes recalling a rotary dial candlestick phone and Duchamp’s Coney Island trick mirror photo, both entail a circle of ten eyes. Figure 1. Page from The BlindMan, No. 2 showing urinal photographed by Alfred Stieglitz. Figure 2. Derivative graphics from The Blind Man, No. 2, copyright by Tim Nowakowski, illustrating the circle of 10 ‘eyes’ bleeding through from the other side of the page, composing in effect a simulation of a candlestick rotary dial phone. Figure 3. Figure 4. Unknown photographer, 5-way portrait of Duchamp. Duchamp having a Spiritualist seance with himself(s), the foreground figure showing the back of his head anticipating the back turned head in Tonsure as well as the Apple-bowl Billiard style smoking pipe. This vaguely compares to the cluster of bachelors in the LG. Divining the presence of eugenics within Marcel Duchamp/Alfred Stieglitz’s Fountain, The BlindMan, No.2, and Rongwrong, reveals some problems in Duchampian scholarship. Traveling from England via a stay with Mable Dodge in Florence, writer/ poet/painter of lampshades Mina Loy, well represented in both Blind Man editions, wrote works which led critics of British literature to characterize her as the eugenics madonna or ‘race mother’. (See this author’s Marcel Duchamp: Eugenics, Race Suicide, dénatalité, State Selective Breeding, Mina Loy, R. Mutt, Roosevelt Mutt and Rongwrong Mutt). Duchamp’s ‘race suicide’ comment here and mandatory government-sponsored natalism suggested in the McBride article, mentioned previously, perplexingly yields no such discourse on race degeneracy among scholars of Duchamp. -

The Paradoxical Poetics of Edith Södergran 813

LINDQVIST / the paradoxical poetics of edith södergran 813 The Paradoxical Poetics of Edith Södergran Ursula Lindqvist In December 1918, Edith Södergran, a 26-year-old poet liv- MODERNISM / modernity ing in an isolated village on the Finno-Russian border, wrote an VOLUME THIRTEEN, NUMBER open letter to the readers of Dagens Press, a Swedish-language ONE, PP 813–833. 1 newspaper in the capital city of Helsinki. The letter, titled © 2006 THE JOHNS “Individuell Konst” [“Individual Art”], introduced Finland’s HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PRESS readers to Södergran’s second volume of poetry, Septemberly- ran [The September Lyre].2 Södergran believed this collection Ursula Lindqvist is embodied a new creative spirit that would call forth a new kind Instructor of Scandina- of individual into being. Because Finland’s readers had had very vian at the University of Colorado at Boulder. little exposure to the radical artistic experimentation that had She completed her been appearing in Europe’s cultural centers for about a decade, Ph.D. in compara- Södergran felt compelled to articulate her vision for this new art tive literature, with a in her homeland. She writes in her letter, “Denna bok är icke certificate in women’s avsedd för publiken, knappast ens för de högre intellektuella and gender studies, kretsarna, endast för de få individer som stå närmast framtidens from the University of gräns” [This book is not intended for an audience, barely even Oregon in 2005. Her research areas are for the higher intellectual circles, only for those few individuals twentieth-century 3 who stand closest to the border of the future]. -

Dada, Cyborgs and the New Woman in New York

3 Dada, Cyborgs and the New Woman in New York Who is she, where is she, what is she – this ‘modern woman’ that people are always talking about? Is there any such creature? Does she look any different looks or talk any different words or think any different thoughts from the late Cleopatra or Mary Queen of Scots or Mrs Browning? Some people think the women are the cause of modernism whatever that is. But then, some people think woman is to blame for everything they don’t like or don’t understand. Cher- chez la femme is man-made advice, of course. (New York Evening Sun, 13 February 1917)1 New York in 1917, particularly with the first Independents Exhibition and the events surrounding it, was in the grip not just of an American flowering of modernist innovation, but of the specific manifestation of New York Dada. The term New York Dada is a retrospective appellation emerging from Zurich Dada and from 1920s popular press reflections on New York modernism; it suggests a more coherent movement than was understood by those living and working in this arena at the time. The many individuals participating in or on the margins of New York Dada included French expatriates such as Francis Picabia and Marcel Duchamp and Americans such as Alfred Steiglitz and Man Ray. Even Ezra Pound was touched by New York Dada, writing two poems for The Little Review in 1921 that explored the interchange between one of its most visible figures, Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, and William Carlos Williams.2 It is not incidental that while the First World War in Europe raged, disturbing the boundaries of ‘natural’ identity and enacting a machinic destruction of cultural and human life, artists and writers in New York 85 A. -

Women Futurists and Parole in Libertà 1914-1924

Between Word and Image: Women Futurists and Parole in Libertà 1914-1924 By Janaya Sandra Lasker-Ferretti A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Italian Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Barbara Spackman, Chair Professor Albert R. Ascoli Professor Harsha Ram Professor Alessia Ricciardi Spring 2012 Between Word and Image: Women Futurists and Parole in Libertà 1914-1924 © 2012 by Janaya Sandra Lasker-Ferretti Abstract Between Word and Image: Women Futurists and Parole in Libertà 1914-1924 by Janaya Sandra Lasker-Ferretti Doctor of Philosophy in Italian Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Barbara Spackman, Chair After F.T. Marinetti, the leader of futurism, theorized parole in libertà (or “words-in- freedom”) in his manifestoes, numerous futurists participated in this verbo-visual practice. Although paroliberismo was a characteristic form of expression that dominated futurist poetics preceding, during, and after World War I, little scholarly work has been done on the “words-in- freedom” authored by women and how they might differ from those created by their male counterparts. Women, outcast as they were by futurism both in theory and often in practice, participated nevertheless in the avant-garde movement known for announcing its “disdain for women” in its “Founding Manifesto” of 1909. This dissertation takes an interdisciplinary approach to analyzing the position of the female futurist and her mixed-media contributions during the years in which paroliberismo was carried out in futurist circles. I examine rare and under-studied verbo-visual works done by women between 1914 and 1924.