Ddc 013 020 Qspqngvrihm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE MYTH of ORPHEUS and EURYDICE in WESTERN LITERATURE by MARK OWEN LEE, C.S.B. B.A., University of Toronto, 1953 M.A., Universi

THE MYTH OF ORPHEUS AND EURYDICE IN WESTERN LITERATURE by MARK OWEN LEE, C.S.B. B.A., University of Toronto, 1953 M.A., University of Toronto, 1957 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OP PHILOSOPHY in the Department of- Classics We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA September, i960 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada. ©he Pttttrerstt^ of ^riitsl} (Eolimtbta FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES PROGRAMME OF THE FINAL ORAL EXAMINATION FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY of MARK OWEN LEE, C.S.B. B.A. University of Toronto, 1953 M.A. University of Toronto, 1957 S.T.B. University of Toronto, 1957 WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 21, 1960 AT 3:00 P.M. IN ROOM 256, BUCHANAN BUILDING COMMITTEE IN CHARGE DEAN G. M. SHRUM, Chairman M. F. MCGREGOR G. B. RIDDEHOUGH W. L. GRANT P. C. F. GUTHRIE C. W. J. ELIOT B. SAVERY G. W. MARQUIS A. E. BIRNEY External Examiner: T. G. ROSENMEYER University of Washington THE MYTH OF ORPHEUS AND EURYDICE IN WESTERN Myth sometimes evolves art-forms in which to express itself: LITERATURE Politian's Orfeo, a secular subject, which used music to tell its story, is seen to be the forerunner of the opera (Chapter IV); later, the ABSTRACT myth of Orpheus and Eurydice evolved the opera, in the works of the Florentine Camerata and Monteverdi, and served as the pattern This dissertion traces the course of the myth of Orpheus and for its reform, in Gluck (Chapter V). -

Baltimore City Historic Preservation Design Guidelines

Baltimore City Historic Preservation Design Guidelines Adopted by the Commission for Historical and Architectural Preservation Baltimore City Department of Planning City of Baltimore, Maryland Chris Ryer Catherine E. Pugh Date of Adoption - December 8, 2015 Director of Planning Mayor Last Update - April 13, 2021 2 Baltimore City Historic Preservation Design Guidelines Table of Contents Chapter 1: Design Guidelines for Building Exteriors . 7 1.1 Identifying and Preserving Historic Building Fabric..............................7 1.2 Masonry..........................................................8 1.3 Wood .......................................................... 13 1.4 Metals.......................................................... 15 1.5 Alternative Materials . 17 1.6 Doors .......................................................... 18 1.7 Windows ........................................................ 20 1.8 Roofing and Gutters ................................................. 25 1.9 Porches, Steps, Railings and Decks . 30 1.10 Paint and Color ................................................... 33 1.11 Lighting ........................................................ 36 1.12 Signage and Awnings ............................................... 37 1.13 Mechanical, Electrical & Plumbing ...................................... 39 1.14 Modern Equipment................................................. 40 1.15 Accessibility . 41 1.16 Lead-Based Paint Hazards . 42 1.17 Alterations and Additions ............................................ 44 -

Hudičev Turn

2014 estival stare f glasbe arly v music efestival estival arly stare music f glasbe efestival Republika Slovenija République française Suomen tasavalta Bosna i Hercegovina Repubblica Italiana Reino de España Republika Hrvatska Република Србија România Rzeczpospolita Polska Republik Österreich Koninkrijk der Nederlanden aš letošnji katalog smo oblikovali nekoliko drugače. Vse do zdaj smo poudarjali gostujoče umetnike in njihove e have decided to make this year’s catalogue different from its forerunners. Up until now we have highlighted the programe, ob tem pa čim bolj smiselno vključevali tudi dodatne vsebine, povezane predvsem s kulturno dediščino. visiting artists and their programmes, all the while including also additional content of interest, in particular from NPrizadevanja, da festivalski program povezujemo z lokalnimi okolji, obstajajo že vrsto let in so bila rodovitna. Wthe field of cultural heritage. Endeavours to link the festival programme with local areas have existed for several Nov koncept kataloga odraža naše želje, da v tesni povezavi vrhunskega evropskega kulturnega programa in nadvse years and have proven fruitful. By closely linking our superb European cultural programme and rich Slovenian heritage, bogate ponudbe te odlične dežele prispevamo, da bo Slovenija postala še bolj zanimiva destinacija na mednarodnem the new concept of the catalogue reflects our desire to help Slovenia become an even more interesting destination on the kulturnem, turističnem in družbenem zemljevidu. Naša udeležba v mednarodnih projektih, kot sta Purpur in eeemerging, international cultural, tourist and social map. Our participation in the international projects such as Purpur and ‘eeemerging’ ali vključevanje v evropske makroregije tako nista le črpanje evropskih sredstev ali obogatitev festivalskega programa kot or involvement in European macro regions therefore mean more than acquiring European funds or enriching the festival takega, ampak tudi močan vsebinski naboj festivala, ki bo še vrsto let plemenitil tako Slovenijo kot Evropo in uspešno programme. -

Download Brochure

Covid-19 Motorcoach Enhanced Disinfecting Procedures on page 28 Picture courtesy of Washington.org hamilton Free customized flyers provided for all tours in this brochure. www.davidtours.travel DUTCH APPLE DINNER THEATRE PENNS PEAK, Jim Thorpe, PA Lancaster PA Roundtrip Luxury Motorcoach Transportation Roundtrip Luxury Motorcoach Transportation The Ultimate Johnny Cash Tribute Always A Bridesmaid (Jan 7 –Feb 14) (Sept. 14) Happy Days (Feb 19– April 3) Lights Out ,The Music of Franki Valli On Your Feet, The Story of Emilio & (Sept. 15) Gloria Estefan (April 15-May 29) Branson Fever (Sept. 21 & 22) Beauty and the Beast (June 3-July 31) Tom Jones Tribute *(Sept. 28) Grumpy Old Men (Aug 5-Sept. 4)) Real Diamond (Sept. 29-30) Mamma Mia! (Sept 9-Nov 6) A Tribute to Elvis (Oct. 12) Miracle on 34th Street (Nov 11-Dec 23) The Jersey Beach Boys (Oct 13) Includes: Luncheon and Show Tribute to Hank Williams SR (Oct 14) 44 paid passengers + 2 Free from $102.00 pp A Tribute to Tony Bennett (Oct 19) 38 paid passengers + 2 Free from $106.00 pp The Glen Miller Orchestra * (Oct 20) Jukebox Saturday Night – A Tribute to the Big Bands (Oct. 21) The Everly Brothers Experience (Oct 26) Islands In The Stream (Oct 27 - 28) *Price higher for this show Includes: Luncheon and Show 44 paid passengers + 2 Free from $94.50 pp 38 paid passengers + 2 Free from $96.50 pp TOBY’S DINNER THEATRE Columbia, MD Roundtrip Luxury Motorcoach Transportation Monty Python’s Spamalot (Jan. 15 to Feb. 28) Shrek the Musical (March 5 to May 2) Godspell (May 7 to June 20) Wednesday Matinee only Includes: Luncheon and Show 44 paid passengers + 2 Free from $109.00 pp 38 paid passengers + 2 Free from $114.00 pp Call for additional 2021 Dinner Theatre Show Schedules Page 2 David Tours & Travel | 866.772.7227 | 215.677.8300 | www.davidtours.travel AMERICAN MUSIC THEATRE Lancaster, PA Roundtrip Luxury Motorcoach Transportation Meal Included Britain's Best (May 18 to June 24) 44 passengers + 2 Free from $98.00 pp 38 Passengers + 2 Free from $102.00 pp Winter Wonderland (Nov. -

Eurydice Program

------~~==~================~======~~~~~~~~~========~r_---------------------------------------------.---. A NOTE fROM THE CHAIR t». C,~VltVlitil Ailt1Vl Department of Communication Welcome to the 2014-2015 season of the Pittsburg State Theatre! This is a smaller production season than usual due to the major move into the Bicknell Family Center for the Arts complex. You can imagine what all the years of tools, equipment, costumes, lumber racks, etc. from our Whitesitt shop will be like to move across campus. Fortunately, that effort, led by Megan Westhoff and Lisa Quinteros, will be a successful one, I'm sure. This transition year for us is one of great excitement and anticipation for the opportunity to further develop and grow our theatre program. It also gives me great pleasure to take this opportunity to thank the alumni of the Pitt State theatre program. The excellent productions created by scores of previous students are, in part, what helped cement the support and belief in the theatre program and the need for a real performing arts center. Whether you currently work in the theatre profession or not, your dedication to Pitt State Theatre while a student is appreciated and respected. You are the legacy of this program and you set the bar high. We honor you and thank you. Lindsey Lockhart (Eurydice) and Gil Cooper (Her Father). The 2014/2015 season begins October 23-25 with You Can't Take It With You, by Moss Hart and George S. Kaufman and directed by yours truly, Cynthia Allan. This raucous comedy, set in the days of the Depression, centers on the Sycamore family and their individualistic approach to life. -

Ljubljana August - September 2014

Maps Events Restaurants Cafés Nightlife Sightseeing Shopping Hotels Ljubljana August - September 2014 Emona Ljubljana’s 2000th birthday promises to be quite the celebration Ptuj Find out more about the oldest town in all of inyourpocket.com Slovenia Issue Nº37 FREE COPY city of opp ortunities In the last twenty years BtC CIty trademark has found Its plaCe under the slovene marketIng sky. today BtC CIty Is not only the BIggest shoppIng Centre, as It has also BeCome an Important BusIness Centre and a CIty wIth sports and Cultural events as well as a plaCe where CreatIve and BusIness Ideas Come to lIfe. therefore the BtC CIty trademark wIll also In the future foCus on CreatIng opportunItIes for a qualIty way of lIfe, InnovatIve Ideas and new vIsIons. www.btc-city.com BTC 2014 Oglas Corpo 143x210+5 In Your Pocket.indd 1 7/22/14 11:19 AM Argentino / Šmartinska 152 (BTC) / 1000 Ljubljana / Slovenija Typical style of an Argentinian hacienda. Always fresh meat, best quality beef from Argentina. Indulge yourself with our grilled specialities. Old Argentinian recipes, on typical grills imported from Argentina. Wine Cellar with over 130 Argentinian Wines www.argentino.si / mobile: +386 31 600 900 InYourPocket 143x210 0313.indd 1 20.3.13 9:31 Contents ESSENTIAL CIT Y GUIDES Arrival & Transport 8 Planes, trains, buses, taxis and transfers Emona 13 Happy 2000th birthday Ljubljana! Culture & Events 15 Festivals, exhibitions, music and much more Restaurants 25 Everything from A to V(egetarian) Cafés 42 Enjoy one of Ljubljana’s favourite pastimes Nightlife -

The First EU Matevž Tomšië: a Tribute to Trubar Planica Step

politicsenviroment 5 culturebusinesssports Marec 2008 The First EU Summit under the Slovenian Presidency, EU leaders launch new phase of Lisbon Strategy Matevž TomšiË: Slovenia has extensive experience with formal and informal but still very effective monopolies A tribute to Trubar paid at the National Museum Planica step further towards nordic centre ISSN 1854-0805 QUoTESofThEfortnight Janez Janša / Prime Minister and current President of the Euro- pean Council/: EU well-equipped to keep tackling current challenges, Brussels, 14 March (The press conference at the end of the spring European Council meeting): The conclusions confirm the tasks we have set ourselves in three key areas. With them we have given the European Union the wherewithal to continue to tackle the most pressing challenges we face at the moment. The new three-year Lisbon Strategy cycle has been launched, fundamental principles for the adoption of the energy and climate change package have been confirmed and responses to current challenges relating to increasing the stability of the financial markets have been agreed. Jose Manuel Barroso /The President of the European Commis- sion/: I congratulate Slovenia on its first Presidency at the EU Summit, Brussels, 14 March. I congratulate the Slovenian Prime Minister, Janez Janša, and his team for the very professional Presi- dency. The success of a Presidency is best judged on the basis of decisions − not by the number of pages, but by the content. If you read the decisions, you will agree that they are very sub- stantive and that they deal with very difficult issues. The Presi- dency has clarified the decisions and achieved major progress in all those areas in comparison to the general agreement a year ago. -

Adaptation and Narrative Structure in the Orpheus Myth Ryan Cadrette

Tracing Eurydice: Adaptation and Narrative Structure in the Orpheus Myth Ryan Cadrette Master’s Thesis in The Department of Communication Studies Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Media Studies) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada August 2013 © Ryan Cadrette, 2013 iii Abstract Tracing Eurydice: Adaptation and Narrative Structure in the Orpheus Myth Ryan Cadrette The primary purpose of this thesis is to postulate a working method of critical inquiry into the processes of narrative adaptation by examining the consistencies and ruptures of a story as it moves across representational form. In order to accomplish this, I will draw upon the method of structuralist textual analysis employed by Roland Barthes in his essay S/Z to produce a comparative study of three versions of the Orpheus myth from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. By reviewing the five codes of meaning described by Barthes in S/Z through the lens of contemporary adaptation theory, I hope to discern a structural basis for the persistence of adapted narrative. By applying these theories to texts in a variety of different media, I will also assess the limitations of Barthes’ methodology, evaluating its utility as a critical tool for post-literary narrative forms. iv Acknowledgments I would like to thank my advisor, Peter van Wyck, for his reassurance that earlier drafts of this thesis were not necessarily indicative of insanity, and, hopefully, for his forgiveness of my failure to incorporate all of his particularly insightful feedback. I would also like to thank Matt Soar and Darren Wershler for agreeing to actually read the peculiar monstrosity I have assembled here. -

Eurydice Without Orpheus

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2011 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2011 Eurydice without Orpheus Nora E. Offen Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2011 Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Offen, Nora E., "Eurydice without Orpheus" (2011). Senior Projects Spring 2011. 5. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2011/5 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Eurydice without Orpheus Senior Project submitted to The Division of Languages and Literature of Bard College by Nora Offen Annandale-on-Hudson, NY May 2011 2 “The love that consists in this: that two solitudes protect and border and greet each other.” For Mike Porter and Luisa Lopez. Acknowledgments I am grateful beyond words to my advisor, Joan Retallack, whose support has made work on this project possible, exhilarating, and deeply gratifying. And to my parents, Neil and Carol Offen, for providing their daughter with a house full of books, and a truly humbling depth of unconditional love. 3 Preface What follows is a poetic and critical reckoning with the Orpheus and Eurydice myth. -

Celebrating Forty Years of Films Worth Talking About

2 NOV 18 6 DEC 18 1 | 2 NOV 18 - 6 DEC 18 88 LOTHIAN ROAD | FILMHOUSEcinema.COM CELEBRATING FORTY YEARS OF FILMS WORTH TALKING ABOUT Move over, Braveheart! Last month saw the culmination of our 40th anniversary celebrations here at Filmhouse, and it has been hugely interesting time (for me at any rate!) comparing the us of now with the us of then. I’ve thoroughly enjoyed spending time talking to Filmhouse’s first Artistic Director, Jim Hickey, and finding out in more detail than I knew what myriad ways the business of running Filmhouse has stayed the same and the as many ways it has not (one of these days I’ll write it all down and you can find out how interesting it is for yourselves!). UK film distribution itself has changed immeasurably – the dawn of the multiplex in the latter half of the 1980s saw to that. Back in 1978, Filmhouse itself was part of a sort of movement that saw the birth of a number of similar venues around the UK whose aim was to show a kind of cinema (predominantly foreign language) that simply was not catered for within mainstream film exhibition. Despite 40 years having passed and much having changed, the notion of an audience-driven, ‘curated’ cinema like Filmhouse remains something of a film exhibition anomaly; and something Jim Hickey wrote 30+ years ago rings just as true today as it did then: “But best of all, the new cinemas are being run by those who care about audiences as well as the films that they have paid to watch.” Now, we’ve got a bit of a first for you in November, for we have metaphorically got into bed with Netflix to give one of their films a hugely deserved, exclusive, short run in a cinema – namely David Mackenzie’s splendidly entertaining Robert the Bruce epic, Outlaw King. -

Der Auf Orpheus (Und/Oder Eurydike)

Reinhard Kapp Chronologisches Verzeichnis (in progress) der auf Orpheus (und/oder Eurydike) bezogenen oder zu beziehenden Opern, Kantaten, Instrumentalmusiken, literarischen Texte, Theaterstücke, Filme und historiographischen Arbeiten (Stand: 5. 10. 2018) Für Klaus Heinrich Da das primäre Interesse bei der folgenden Zusammenstellung musikgeschichtlicher Art ist, stehen am Anfang der Einträge die Komponisten, soweit es sich um musikalische Werke handelt – auch dann, wenn die zeitgenössische Einschätzung wohl eher den Librettisten die Priorität eingeräumt hätte. Unter einem bestimmten Jahr steht wiederum die Musik an erster Stelle, gefolgt von Theater, Film, Dichtung und Wissenschaft. Vielfach handelt es sich um Nachrichten aus zweiter Hand; ob etwa die genannten Stücke sich erhalten haben, ließ sich noch nicht in allen Fällen ermitteln. Doch ist u.U. die bloße Tatsache der Aufführung schon Information genug. Musik- bzw. literaturwissenschaftliche Sekundärliteratur zu einzelnen Stücken bzw. Texten wurde in der Regel nicht verzeichnet. Die Liste beruht nicht auf systematischen Erhebungen, daher sind die Angaben von unterschiedlicher Genauigkeit und Zuverlässigkeit. Ergänzungen und Korrekturen werden dankbar entgegengenommen. Eine erste rudimentäre Version erschien in: talismane. Klaus Heinrich zum 70. Geburtstag , hsg. v. Sigrun Anselm und Caroline Neubaur, Basel – Frankfurt/M. 1998, S.425ff. Orphiker: Schule philosophierender Dichter, benannt nach ihrem legendären Gründer Orpheus – 8./7. Jh. v. Chr. Ischtars Fahrt in das Land ohne Heimkehr (altsumerische Vorform des Mythos, ins dritte vorchristliche Jahrtausend zurückreichend) – aufgezeichnet im 7. Jh. v. Chr. Ibykos (Lyriker), Fragment aus zwei Worten „berühmter Orpheus“ – 6. Jh. v. Chr. Unter den Peisistratiden soll Onomakritos am Tyrannenhof die Orphischen Gedichte gesammelt haben – 6. Jh. v. Chr.? Simonides v. Keos (?), Fragment 62 (bzw. -

Acta Historiae Artis Slovenica 24|1 2019 Umetnostnozgodovinski Inštitut Franceta Steleta Zrc Sazu 2019

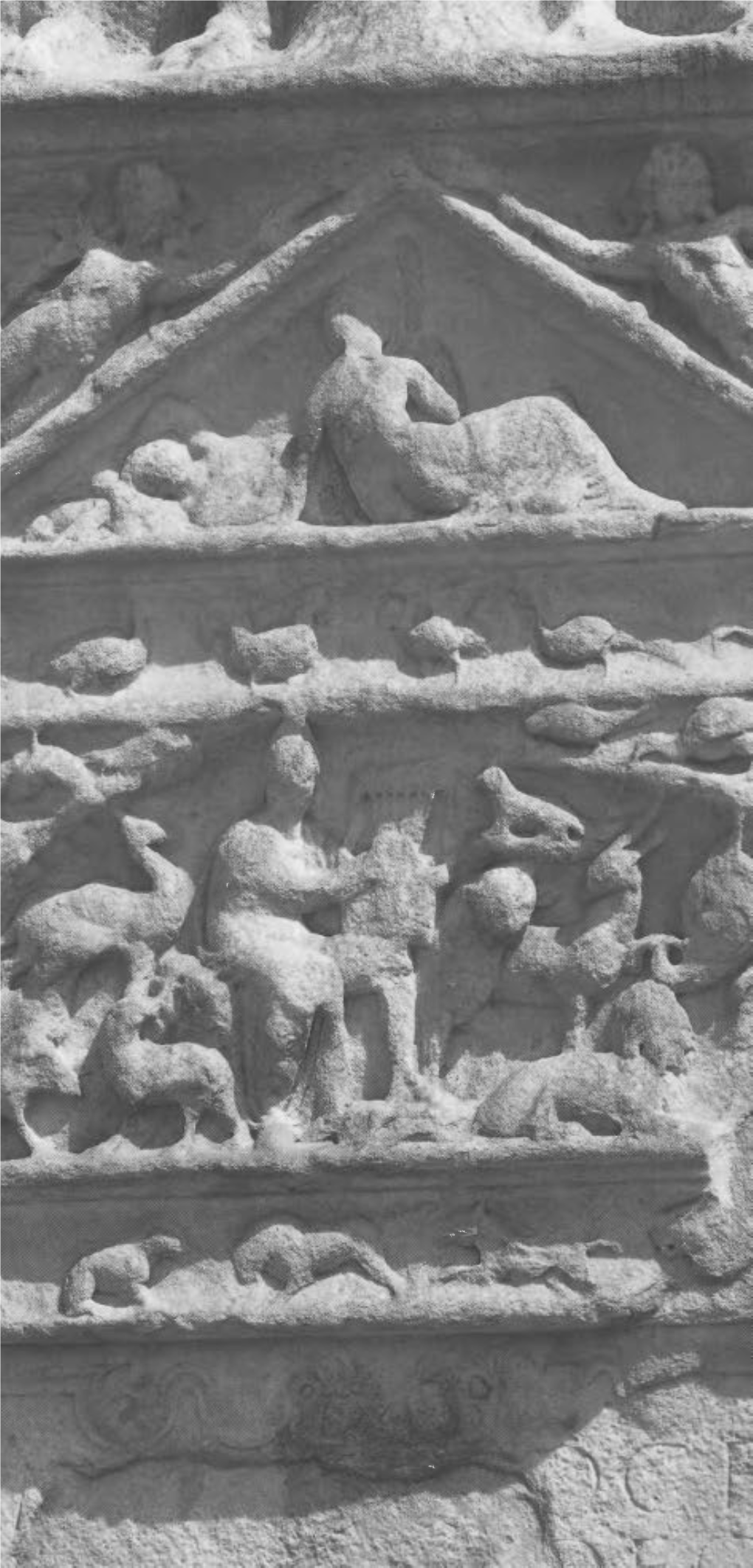

ACTA HISTORIAE ARTIS SLOVENICA 24|1 2019 UMETNOSTNOZGODOVINSKI INŠTITUT FRANCETA STELETA ZRC SAZU 2019 1 | 24 Vsebina • Contents Katarina Šmid, Orfej med živalmi na ptujskem Orfejevem spomeniku – upodobitev ekfraze Filostrata Mlajšega? • Orpheus among the Animals on the Orpheus Monument in Ptuj: An Echo of the Ekphrasis by Philostratus the Younger? Jure Vuga, Podoba samogibljive skulpture malika, mehaničnega čudesa ali »avtomata« na Kranjskem oltarju • A Depiction of a Self-moving Sculpture of an Idol, a Mechanical Marvel or Automaton in the Krainburg Altarpiece Boris Golec, Višnjegorski slikarji 17. in 18. stoletja, njihovo socialno in naročniško okolje. Frančišek Karel Mučeništvo sv. Kancija, Kancijana, (Francesco) Faenzi, Franc Faenzi, Janez Jakob Menhard (Mönhardt), Jakob Killer, Karel Ludvik Gentilli, Peter Kancijanile in Prota (izrez), Kranjski oltar, Straspurger, Franc Anton Nirenberger, Franc Ksaver Nirenberger, Anton Nirenberger • 17th and 18th Century ok. 1500, © Belvedere, Dunaj Painters from Višnja Gora, their Social Environment and Commissioners. Franz Karl (Francesco) Faenzi, Franz Faenzi, Johann Jakob Menhard (Mönhardt), Jakob Killer, Karl Ludwig Gentilli, Peter Straspurger, Franz Anton Nirenberger, Franz Xaver Nirenberger, Anton Nirenberger Renata Komić Marn, »Če bo hotel muzej pridobiti kaj boljših stvari, bo moral za nakup tvegati večje vsote.« Nakupi za Narodni muzej na dražbi Szapáryjeve zbirke v Murski Soboti • “If the museum wishes to obtain better things, it will have to risk higher sums.” The Acquisitions for the National Museum at the Auction of the Szapáry Collection in Murska Sobota Barbara Vodopivec, Restitucija predmetov kulturne dediščine iz Avstrije v Jugoslavijo po letu 1945 • Restitution of Objects of Cultural Heritage from Austria to Yugoslavia after 1945 Jure Volčjak, Cerkve goriške nadškofije na Kranjskem v času nadškofa Karla Mihaela grofa Attemsa.