Sexual Orientation, Gender, & Self-Styling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I'm Still Here, Still: a Performance by Alexandra Billings

THEMEGUIDE I’m Still Here, Still TRANS REPRESENTATION BY THE A PERFORMANCE BY NUMBERS o GLAAD¹ has documented 102 episodes and non-recurring ALEXANDRA BILLINGS storylines of scripted TV featuring transgender characters Thursday, January 26, 2017, at 7 p.m. since 2002, and 54 percent of those were negative Bing Theatre representations. Transgender characters were often victims or killers, and anti-trans slurs were present in 61 Is Hollywood “Transparent”? percent of the episodes. o In 2010, Trans Media Watch conducted a survey in which Identity and “Mis”representation 21 percent of respondents said they had experienced at least one instance of verbal abuse they felt was related in the Industry to negative media representations of trans or intersex Friday, January 27, 2017, at 3 p.m. people. 20 percent had experienced negative reactions McClintock Theatre at work that they could trace to items in the media. o While TV shows like Transparent and Orange Is the New Black represent a significant improvement in trans visibility, 80 percent of trans students still feel unsafe in school and in 2015 more trans people were reported murdered than in any other year on record. DEFINITIONS CISGENDER: This adjective applies to a person whose gender identity corresponds with the sex they were identified as having at birth. MEDIA REPRESENTATION: The way the media portrays a given social group, community, or idea. TRANSGENDER: This adjective applies to a person whose gender identity differs from the sex they were identified as having at birth. TIMELINE OF TRANS VISIBILITY IN U.S. DOMINANT CULTURE 1952 Christine Jorgensen, a former Army private, becomes the first American to undergo what was then called a “sex change” operation. -

Story Spark Activity-Fun Crazy Weird Hair Store V4

Word Salon Menu Story Sparks Season 3, Episode 12: Fun Crazy Weird Hair Store/The Mountain Fart Creating silly hair looks with your own Word Salon menu! Your Creator Club Notebook, blank paper to draw your looks, markers Welcome to our Word Salon In the song “Fun Crazy Weird Hair Store,” based on a story by a kid named Sylvia from New Jersey, there is a salon with a menu of options for hairstyles that are all super silly. It sounds like a place we definitely want to go, but we can’t picture what the hairstyles look like! Let's think of ways to be even more descriptive with a Word Salon Menu! What EXACTLY makes these styles SILLY? Is it the color? The length? The style? Color Menu blue, teal, red, orange, green, rainbow, rose gold, copper, glitter, platinum blonde, ultraviolet, infrared, grey, lavender, mermaid, silver, highlights, frosted tips, balayage, SOMETHING ELSE TOTALLY FUN? Length Menu buzz cut, bob, chin length, as long as a football field, one millimeter, foot length, giraffe neck length, as long as a lion's mane, as tall as the Empire State Building, SOMETHING ELSE TOTALLY WILD? Style Menu bangs, mullet, bouffant, flat top, braid, French twist, bowl cut, crown braid, spiky, mohawk, double buns, finger waves, mop top, ringlets, slicked back, updo, bouncy curl, SOMETHING ELSE TOTALLY WEIRD? To create your look, combine these words to create a SILLY style from your own imagination! It's easy to do: 1. Pick one color, one length, and one style. Take words from our lists, or make up your own! 2. -

Julia, Imagen Givenchy Su Esposo La Asesinó Caída De

EXCELSIOR MIÉRCOLES 10 DE DICIEMBRE DE 2014 [email protected] Resumen. Pharrell Williams encabeza la lista de @Funcion_Exc popularidad de Billboard. Y los escándalos del año>6 y 13 MAÑANA SE ESTRENA EN DOS MIL 400 SALAS UNA ÚLTIMA Los actores queAVENTURA participaron en El Hobbit: La batalla de los cinco ejércitos mostraron su satisfacción de poder participar en la tercera entrega de la saga dirigida por Peter Jackson >8 y 9 Fotos: Cortesía Warner Bros. Foto: Tomada de Instagram Givenchy Foto: Tomada de YouTube Foto: AP JULIA, IMAGEN GIVENCHY CAÍDA DE ELTON, VIRAL SU ESPOSO LA ASESINÓ PARÍS.- La actriz estadunidense Julia Roberts será la Más de un millón de visitas en sólo 24 horas alcanzó La actriz y modelo Stephanie Moseley, protagonista del nueva imagen de la casa francesa de moda Givenchy el video en el que se ve al cantante Elton John en una reality televisivo Hit The Floor, fue asesinada a tiros por para su campaña de primavera/verano 2015. aparatosa caída al presenciar un partido de tenis. Earl Hayes, quien era su esposo. El hombre se quitó la En las imágenes en blanco y negro, la actriz mues- El músico de 67 años asistió a un evento en el vida después de haberla matado. tra un aspecto andrógino, ataviada con una blusa ne- Royal Albert Hall de Londres, donde alentaba a su Trascendió que se habían separado hace dos años, gra con mangas transparentes. equipo contra el de la exjugadora profesional Billie Jean luego de un supuesto amorío con el músico Trey Songz, La sesión fue realizada por la importante empresa King, pero al intentar sentarse se suscitó el incidente. -

40 Cultural Shifts Shaping Our World

EDGES, 2021 40 Cultural Shifts Shaping Our World JANUARY 2021 ©2021 TBWA\Worldwide. All rights reserved. Proprietary and Confidential YEAR ZERO Every January brings talk of fresh starts, exciting trends, Within this story, you will find 40 meaningful cultural shifts and cultural phenomena. But this time, the implications shaping our world. These shifts are born from a global process are much larger. The pandemic has precipitated a that emphasizes the expertise of over 300 TBWA “Culture cosmic reshuffle of global realities, social norms and Spotters”—leveraging insight from Bogota to Berlin, Kigali to individual beliefs. A world is ending, and another is being Kuala Lumpur, New Delhi to New York. born. 2021 isn’t just another year, it’s Year Zero. And so this isn’t just a trend report. It’s a glimpse into a new chapter of our history. Culture is fast, often confusing, and sometimes misleading. We hope that these Edges bring optimism, inspiration for growth, and a clear direction forward. Culture is our story. And more In the face of seismic change, we find ourselves torn than ever before, it’s up to us to write a chapter we’ll be proud of. between fight and flight, dark and light, between the pullback of conservatism and the push forward of imagination. Radical transformation is never Welcome to 2021. Welcome to Year Zero. comfortable, but brighter tomorrows are ahead. Our 2021 Edges tell this hopeful story in six chapters: Chaos. Preservation. Advancement. Identity. Liberation. Rebirth. ©2021 TBWA\Worldwide. All rights reserved. Proprietary and Confidential Edges must be rooted in human values, be 1 recognizable through consumer behaviors, and lead to clear business implications. -

Lesbian and Gay Music

Revista Eletrônica de Musicologia Volume VII – Dezembro de 2002 Lesbian and Gay Music by Philip Brett and Elizabeth Wood the unexpurgated full-length original of the New Grove II article, edited by Carlos Palombini A record, in both historical documentation and biographical reclamation, of the struggles and sensi- bilities of homosexual people of the West that came out in their music, and of the [undoubted but unacknowledged] contribution of homosexual men and women to the music profession. In broader terms, a special perspective from which Western music of all kinds can be heard and critiqued. I. INTRODUCTION TO THE ORIGINAL VERSION 1 II. (HOMO)SEXUALIT Y AND MUSICALIT Y 2 III. MUSIC AND THE LESBIAN AND GAY MOVEMENT 7 IV. MUSICAL THEATRE, JAZZ AND POPULAR MUSIC 10 V. MUSIC AND THE AIDS/HIV CRISIS 13 VI. DEVELOPMENTS IN THE 1990S 14 VII. DIVAS AND DISCOS 16 VIII. ANTHROPOLOGY AND HISTORY 19 IX. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 24 X. EDITOR’S NOTES 24 XI. DISCOGRAPHY 25 XII. BIBLIOGRAPHY 25 I. INTRODUCTION TO THE ORIGINAL VERSION 1 What Grove printed under ‘Gay and Lesbian Music’ was not entirely what we intended, from the title on. Since we were allotted only two 2500 words and wrote almost five times as much, we inevitably expected cuts. These came not as we feared in the more theoretical sections, but in certain other tar- geted areas: names, popular music, and the role of women. Though some living musicians were allowed in, all those thought to be uncomfortable about their sexual orientation’s being known were excised, beginning with Boulez. -

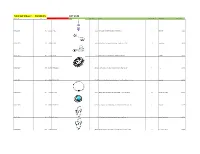

Total Lot Value = $5,520.15 LOT #149 Location Id Lot # Item Id Sku Image Store Price Model Store Quantity Classification Total Value

Total Lot Value = $5,520.15 LOT #149 location_id Lot # item_id sku Image store_price model store_quantity classification Total Value A10-S11-D009 149 143692 BR-2072 $11.99 Pink CZ Sparkling Heart Dangle Belly Button Ring 1 Belly Ring $11.99 A10-S11-D010 149 67496 BB-1011 $4.95 Abstract Palm Tree Surgical Steel Tongue Ring Barbell - 14G 10 Tongue Ring $49.50 A10-S11-D013 149 113117 CA-1346 $11.95 Triple Bezel CZ 925 Sterling Silver Cartilage Earring Stud 6 Cartilage $71.70 A10-S11-D017 149 150789 IX-FR1313-10 $17.95 Black-Plated Stainless Steel Interlocked Pattern Ring - Size 10 1 Ring $17.95 A10-S11-D022 149 168496 FT9-PSA15-25 $21.95 Tree of Life Gold Tone Surgical Steel Double Flare Tunnel Plugs - 1" - Pair 2 Plugs Sale $43.90 A10-S11-D024 149 67502 CBR-1004 $10.95 Hollow Heart .925 Sterling Silver Captive Bead Ring - 16 Gauge CBR 10 Captive Ring , Daith $109.50 A10-S11-D031 149 180005 FT9-PSJ01-05 $11.95 Faux Turquoise Tribal Shield Surgical Steel Double Flare Plugs 4G - Pair 1 Plugs Sale $11.95 A10-S11-D032 149 67518 CBR-1020 $10.95 .925 Sterling Silver Hollow Star Vertical Captive Bead Ring - 16G 4 Captive Ring , Daith $43.80 A10-S11-D034 149 67520 CBR-1022 $10.95 .925 Sterling Silver Hollow Butterfly Vertical Captive Bead Ring - 16G 2 Captive Ring , Daith $21.90 A10-S11-D035 149 67521 CBR-1023 $8.99 .925 Sterling Silver Hollow Cross Vertical Captive Bead Ring - 16G 2 Captive Ring , Daith $17.98 A10-S11-D036 149 67522 NP-1001 $15.95 Triple CZ .925 Sterling Silver Nipple Piercing Barbell Shield 8 Nipple Ring $127.60 A10-S11-D038 149 -

BIS Hanoi Student Magazine

NOVUS BIS Hanoi stud ent magazine CULTURE J A N U A R Y 2 0 2 1 Editorial Welcome to the 2nd issue of Novus, BIS’s student-led school magazine. Our objective is to bring you a new perspective on affairs which might have passed you by. In this issue, we invite you to engage with culture. It is indisputable that culture is a fundamental element of human life; it not only enriches life but also creates a connection between people. This fundamental nature relies on inspiration, which then becomes dispersed. Such sequence goes on and on, anytime and anywhere. Thus, it is inevitable that culture is created - unless humans stop thinking. When you define the term ‘culture’, it is likely that you will ponder an Interview with a Julliard Dance image of archaic historical products or traditional arts of a country. specialist However, if it brings people together and becomes a custom, it can be [page 18~22] considered as culture. New cultural affairs have sprung up in contemporary society - one example of this is K-Pop. If you are interested in how it became viral, see K-Pop Culture [page 3~4]. Another term which has developed in the recent COVID-19 era is Cottagecore, an aesthetic which celebrates rural life; see page 13~ 14 which provides a big picture of such Gen-Z subculture. Celebrating all the cultures which were created, it leads to an ultimate question of why culture is important. A key for that reason is provided in Why is culture important? [page 11~12]. -

“Down the Rabbit Hole: an Exploration of Japanese Lolita Fashion”

“Down the Rabbit Hole: An Exploration of Japanese Lolita Fashion” Leia Atkinson A thesis presented to the Faculty of Graduate and Post-Doctoral Studies in the Program of Anthropology with the intention of obtaining a Master’s Degree School of Sociology and Anthropology Faculty of Social Sciences University of Ottawa © Leia Atkinson, Ottawa, Canada, 2015 Abstract An ethnographic work about Japanese women who wear Lolita fashion, based primarily upon anthropological field research that was conducted in Tokyo between May and August 2014. The main purpose of this study is to investigate how and why women wear Lolita fashion despite the contradictions surrounding it. An additional purpose is to provide a new perspective about Lolita fashion through using interview data. Fieldwork was conducted through participant observation, surveying, and multiple semi-structured interviews with eleven women over a three-month period. It was concluded that women wear Lolita fashion for a sense of freedom from the constraints that they encounter, such as expectations placed upon them as housewives, students or mothers. The thesis provides a historical chapter, a chapter about fantasy with ethnographic data, and a chapter about how Lolita fashion relates to other fashions as well as the Cool Japan campaign. ii Acknowledgements Throughout the carrying out of my thesis, I have received an immense amount of support, for which I am truly thankful, and without which this thesis would have been impossible. I would particularly like to thank my supervisor, Vincent Mirza, as well as my committee members Ari Gandsman and Julie LaPlante. I would also like to thank Arai Yusuke, Isaac Gagné and Alexis Truong for their support and advice during the completion of my thesis. -

Beauty Trends 2015

Beauty Trends 2015 HAIR CARE EDITION (U.S.) The image The image cannot be cannot be displayed. displayed. Your Your computer computer may not have may not have enough enough memory to memory to Intro open the open the With every query typed into a search bar, we are given a glimpse into user considerations or intentions. By compiling top searches, we are able to render a strong representation of the United States’ population and gain insight into this specific population’s behavior. In our Google Beauty Trends report, we are excited to bring forth the power of big data into the hands of the marketers, product developers, stylists, trendsetters and tastemakers. The goal of this report is to share useful data for planning purposes accompanied by curated styles of what we believe can make for impactful trends. We are proud to share this iteration and look forward to hearing back from you. Flynn Matthews | Principal Industry Analyst, Beauty Olivier Zimmer | Trends Data Scientist Yarden Horwitz | Trends Brand Strategist Photo Credit: Blind Barber (Men’s Hair), Meladee Shea Gammelseter (Women’s Hair), Andrea Grabher/Christian Anwander (Colored Hair), Catface Hair (Box & Twist Braids), Maria Valentino/MCV photo (Goddess Braid) Proprietary + Confidential Methodology QUERY To compile a list of accurate trends within the Jan-13 Aug-13 Jan-14 Aug-14 Jan-15 Aug-15 beauty industry, we pulled top volume queries related to the beauty category and looked at their monthly volume from January 2013 to August 2015. We first removed any seasonal effect, and DE-SEASONALIZED QUERY then measured the year-over-year growth, velocity, and acceleration for each search query. -

Computer Based Art 2 Computer Based Art 3

1 Computer based art 2 Computer based art 3 Computer based art 4 Computer based art ??5 Buzzanca vs Buzzanca6 7 9 L’arte contemporanea (quale sia la data d’inizio che le volessimo attribuire) è stata caratterizzata, lo si è già accennato, dalla adozione di materiali di espressione artistica i più disparati possibili. La scelta di utilizzare il computer per esprimere il fare artistico, per sviluppare un linguaggio della manifestazione artistica diviene strettamente connesso • al sistema operativo, • all’applicazione, • alla pagina definita dal codice ed • alle teorie che del computer prendono in considerazione gli aspetti logici, simbolici; E’ possibile attivare sul computer, in maniera chiara e fortemente innovativa, una rappresentazione del proprio agire artistico. La vera innovazione, sappiamo bene, non consiste certo nella tastiera più o meno user friendly ma nella capacità di usare il mezzo informatico alla stessa stregua dei più disparati materiali presi a base nelle rappresentazioni dell’arte contemporanea. 13 14 15 16 17 Quali possono essere, allora, le strategie per l'archiviazione e, principalmente, per la conservazione delle arti digitali e di altre pratiche artistiche contemporanee di natura effimera o variabile e comunque strettamente dipendente da un medium la cui sopravvivenza è abbondantemente messa in crisi dagli stessi assunti metodologici della tecnologia adottata? Trovo in questo senso diagrammatica, esulando solo per un attimo dalle arti figurative (che includono figurazione e rappresentazione comunque iconica) la composizione musicale Helicopter String Quartet di Karlheinz Stockhausen che prevede che i quattro esecutori siano ciascuno su un differente elicottero ed eseguano sincronicamente l’esecuzione essendo tra loro collegati mediante apparecchi di registrazione e trasmissione coordinati da terra dal regista o meglio ancora dal direttore tecnologico dell’orchestra. -

Hairstyle Email Course TIP #1

Hairstyle Email Course TIP #1 Subject: Why you need to understand your hair type before changing your hairstyle ====================================================================== EMAIL Hi Tanner, Thank you for requesting the "7 Steps To Discovering Your Perfect Hairstyle" email course. These 7 short lessons will help you find the hairstyle that's perfect for you. A style that fits your unique face shape, personality and lifestyle. You will receive one email a day for 7 days. Each email will contain a link to the "lesson" (takes about 5 minutes to read). If you go through this course you'll walk away with a better understanding of how to select a style that brings out the best in you. So without further ado let's dive into Lesson #1: Understanding Your Hair Type. Click here to learn more. ============================================= LANDING PAGE The 4 Main Men's Hair Types One of the most important factors when it comes to choosing the hairstyle that's right for you has to do with your hair type. The density and texture of your hair will influence the "parameters" you have to work within when it comes to your new style. Below are the four main hair types along with tips for each. 1. Thick Hair Tips [Insert thick hair photo to the right] * If you have really thick hair, ask the stylist to thin it for you so it won't lay so thick at the bottom. * Choose a hairstyle that has a "layered cut" (true for both short & long hair). Otherwise it will lay as one big pile. * Comb or brush your hair to reduce the "poofiness". -

“Punk Rock Is My Religion”

“Punk Rock Is My Religion” An Exploration of Straight Edge punk as a Surrogate of Religion. Francis Elizabeth Stewart 1622049 Submitted in fulfilment of the doctoral dissertation requirements of the School of Language, Culture and Religion at the University of Stirling. 2011 Supervisors: Dr Andrew Hass Dr Alison Jasper 1 Acknowledgements A debt of acknowledgement is owned to a number of individuals and companies within both of the two fields of study – academia and the hardcore punk and Straight Edge scenes. Supervisory acknowledgement: Dr Andrew Hass, Dr Alison Jasper. In addition staff and others who read chapters, pieces of work and papers, and commented, discussed or made suggestions: Dr Timothy Fitzgerald, Dr Michael Marten, Dr Ward Blanton and Dr Janet Wordley. Financial acknowledgement: Dr William Marshall and the SLCR, The Panacea Society, AHRC, BSA and SOCREL. J & C Wordley, I & K Stewart, J & E Stewart. Research acknowledgement: Emily Buningham @ ‘England’s Dreaming’ archive, Liverpool John Moore University. Philip Leach @ Media archive for central England. AHRC funded ‘Using Moving Archives in Academic Research’ course 2008 – 2009. The 924 Gilman Street Project in Berkeley CA. Interview acknowledgement: Lauren Stewart, Chloe Erdmann, Nathan Cohen, Shane Becker, Philip Johnston, Alan Stewart, N8xxx, and xEricx for all your help in finding willing participants and arranging interviews. A huge acknowledgement of gratitude to all who took part in interviews, giving of their time, ideas and self so willingly, it will not be forgotten. Acknowledgement and thanks are also given to Judy and Loanne for their welcome in a new country, providing me with a home and showing me around the Bay Area.