On the Names of States: Naming System of States Based on the Country Names and on the Public Law Components of State Titles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

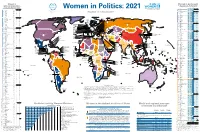

Women in Ministerial Positions, Reflecting Appointments up to 1 January 2021

Women in Women in parliament The countries are ranked and colour-coded according to the percentage of women in unicameral parliaments or the lower house of parliament, ministerial positions reflecting elections/appointments up to 1 January 2021. The countries are ranked according to the percentage of women in ministerial positions, reflecting appointments up to 1 January 2021. Rank Country Lower or single house Upper house or Senate % Women Women/Seats % Women Women/Seats Rank Country % Women Women Total ministers ‡ Women in Politics: 2021 50 to 65% 50 to 59.9% 1 Rwanda 61.3 49 / 80 38.5 10 / 26 1 Nicaragua 58.8 10 17 2 Cuba 53.4 313 / 586 — — / — 2 Austria 57.1 8 14 3 United Arab Emirates 50.0 20 / 40 — — / — ” Belgium 57.1 8 14 40 to 49.9% ” Sweden 57.1 12 21 4 Nicaragua 48.4 44 / 91 — — / — 5 Albania 56.3 9 16 Situation on 1 January 2021 5 New Zealand 48.3 58 / 120 — — / — 6 Rwanda 54.8 17 31 6 Mexico 48.2 241 / 500 49.2 63 / 128 7 Costa Rica 52.0 13 25 7 Sweden 47.0 164 / 349 — — / — 8 Canada 51.4 18 35 8 Grenada 46.7 7 / 15 15.4 2 / 13 9 Andorra 50.0 6 12 9 Andorra 46.4 13 / 28 — — / — ” Finland 50.0 9 18 10 Bolivia (Plurinational State of) 46.2 60 / 130 55.6 20 / 36 ” France 50.0 9 18 11 Finland 46.0 92 / 200 — — / — ” Guinea-Bissau* 50.0 8 16 12 South Africa 45.8 182 / 397 41.5 22 / 53 ” Spain 50.0 11 22 13 Costa Rica 45.6 26 / 57 — — / — 40 to 49.9% 14 Norway 44.4 75 / 169 — — / — 14 South Africa 48.3 14 29 15 Namibia 44.2 46 / 104 14.3 6 / 42 15 Netherlands 47.1 8 17 Greenland Latvia 16 Spain 44.0 154 / 350 40.8 108 / 265 16 -

A Changing of the Guards Or a Change of Systems?

BTI 2020 A Changing of the Guards or A Change of Systems? Regional Report Sub-Saharan Africa Nic Cheeseman BTI 2020 | A Changing of the Guards or A Change of Systems? Regional Report Sub-Saharan Africa By Nic Cheeseman Overview of transition processes in Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Republic of the Congo, Côte d'Ivoire, Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Gabon, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Africa, South Sudan, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe This regional report was produced in October 2019. It analyzes the results of the Bertelsmann Transformation Index (BTI) 2020 in the review period from 1 February 2017 to 31 January 2019. Author Nic Cheeseman Professor of Democracy and International Development University of Birmingham Responsible Robert Schwarz Senior Project Manager Program Shaping Sustainable Economies Bertelsmann Stiftung Phone 05241 81-81402 [email protected] www.bti-project.org | www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/en Please quote as follows: Nic Cheeseman, A Changing of the Guards or A Change of Systems? — BTI Regional Report Sub-Saharan Africa, Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung 2020. https://dx.doi.org/10.11586/2020048 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0). Cover: © Freepick.com / https://www.freepik.com/free-vector/close-up-of-magnifying-glass-on- map_2518218.htm A Changing of the Guards or A Change of Systems? — BTI 2020 Report Sub-Saharan Africa | Page 3 Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................... -

Freak the Mighty Vocabulary List Chapters 1-8 Word Meaning 1

Freak the Mighty Vocabulary List Chapters 1-8 Word Meaning 1. Unvanquished not able to be defeated 2. Scuttle A short, hurried run; to scurry 3. Perspective An accurate point of view; objectively 4. Strutting Walking with “attitude” 5. Sobriquet A nickname 6. Hulking Clumsy and heavy 7. Trajectory The curve described by a rocket in flight 8. Glimpse A brief sight or view 9. Hunkering To lumber along; walk or move slowly or aimlessly 10. Postulate To claim or assume the existence or truth of 11. Deficiency Incompleteness; insufficiency 12. Converging Incline toward each other 13. Evasive Avoiding or seeking to avoid trouble or difficulties 14. Propelled To cause to move forward 15. Demeanor Conduct or behavior 16. Depleted Supply is used up 17. Cretin A stupid or mentally defective person 18. Quest An adventurous expedition 19. Invincible Incapable of being conquered or defeated 20. Expel Discharge or eject 21. Archetype A collectively inherited pattern of thought present in people Freak the Mighty Vocabulary List Chapters 9 -18 Word Meaning 1.steed A high-spirited horse 2. pledge A solemn promise 3. oath A formally issued statement or promise 4. gruel A thin porridge 5. tenement Run-down, overcrowded apartment houses 6. yonder That place over there 7. optimum The best result under specific conditions 8. Holy Grail A sacred object 9. Injustice Violation of the rights of others; unfair action 10. Urgency Requiring speedy action or attention 11. Miraculous Marvelous; of the nature of a miracle 12. Deprived Lacking the necessities of life 13. Trussed To tie or secure closely 14. -

A Genealogical Handbook of German Research

Family History Library • 35 North West Temple Street • Salt Lake City, UT 84150-3400 USA A GENEALOGICAL HANDBOOK OF GERMAN RESEARCH REVISED EDITION 1980 By Larry O. Jensen P.O. Box 441 PLEASANT GROVE, UTAH 84062 Copyright © 1996, by Larry O. Jensen All rights reserved. No part of this work may be translated or reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, including photocopying, without permission in writing from the author. Printed in the U.S.A. INTRODUCTION There are many different aspects of German research that could and maybe should be covered; but it is not the intention of this book even to try to cover the majority of these. Too often when genealogical texts are written on German research, the tendency has been to generalize. Because of the historical, political, and environmental background of this country, that is one thing that should not be done. In Germany the records vary as far as types, time period, contents, and use from one kingdom to the next and even between areas within the same kingdom. In addition to the variation in record types there are also research problems concerning the use of different calendars and naming practices that also vary from area to area. Before one can successfully begin doing research in Germany there are certain things that he must know. There are certain references, problems and procedures that will affect how one does research regardless of the area in Germany where he intends to do research. The purpose of this book is to set forth those things that a person must know and do to succeed in his Germanic research, whether he is just beginning or whether he is advanced. -

Samuel Wilson, Who, Along with an Older Brother, Ebenezer, Supplied the Army with Meat from Troy, New York

Memoranda and Documents A NOTE ON THE ORIGINS OF “UNCLE SAM,” 1810–1820 donald r. hickey ONVENTIONAL wisdom holds that “Uncle Sam,” the popular C personification for the United States government, was inspired during the War of 1812 by Samuel Wilson, who, along with an older brother, Ebenezer, supplied the army with meat from Troy, New York. The Wilsons employed as many as two hundred people, includ- ing many relatives who had moved to Troy to work in the diversified family business. The nieces and nephews referred to Sam Wilson as Uncle Sam, and such was his friendly and easy-going nature that the nickname caught on among other employees and townspeople. Due to confusion over the meaning of the abbreviation “U.S.,” which was stamped on army barrels and supply wagons, the nickname suppos- edly migrated from Wilson to the federal government in 1812.1 The author has incurred numerous debts in writing this article. Georg Mauerhoff of NewsBank provided indispensable guidance in using the NewsBank databases, es- pecially the Readex newspaper collection. Charissa Loftis of the U.S. Conn Library at Wayne State College tracked down some pertinent information, and (as always) Terri Headley at the Interlibrary Loan Desk proved adept at borrowing works from other libraries. Many years ago Mariam Touba of the New-York Historical Society and Nancy Farron of the Troy Public Library shared typed transcripts of crucial documents. The author owes a special debt to Matthew Brenckle, Research Historian at the USS Constitution Museum, who brought the Isaac Mayo diary to his attention and shared his views on the document. -

PCC Task Group for Coding Non-RDA Entities in Nars: Final Report November 16, 2020

1 PCC Task Group for Coding non-RDA Entities in NARs: Final Report November 16, 2020 Contents Executive summary 2 Recommendations 2 Charge, background, and scope 3 Purposes served by coding entity type 4 Purposes served by coding descriptive convention 4 Data model 5 Recommended terms for 075 6 Recommended coding for 040 $e 6 Implementation issues 7 Platform for hosting vocabulary 7 Maintenance and development of the vocabulary (extensibility) 7 Collaboration with DNB 8 Training and documentation 8 Out of scope issues 9 Fictitious characters and pseudonyms 9 Shared pseudonyms 11 Descriptive conventions for non-RDA entities 11 Elements for non-agent entities 12 Division of the world 12 Legacy data 13 Examples 13 Appendix: Charge and roster 18 2 Executive summary With the introduction of the LRM data model in the beta RDA Toolkit, it became necessary to distinguish RDA Agent and non-Agent entities in the LC Name Authority File. The PCC Policy Committee (PoCo) determined that 075 $a in the MARC authority format could be used to record this distinction, and that it would also be necessary to designate a different descriptive convention in 040 $e. PoCo charged the present Task Group to make recommendations for coding these subfields. In considering its recommendations, the Task Group identified the core use cases that would need to be met, and evaluated several potential data models. An important concern was that the proposed vocabulary be simple to maintain and apply. These considerations led the Task Group to recommend a small set of terms reflecting categories that are given distinct treatment in cataloging practice. -

Statlig Minoritetspolitikk I Israel

Statlig minoritetspolitikk i Israel Et studie av staten Israels politikk overfor den palestinske minoriteten i landet. Gada Ezat Azam Masteroppgave, Institutt for Statsvitenskap UNIVERSITETET I OSLO Våren 2007 (32 290 ord) 2 Forord Det er en rekke personer som fortjener en stor takk for den hjelp og støtte de har gitt meg under arbeidet med masteroppgaven. Først og fremst vil jeg takke mine to veiledere, Anne Julie Semb ved Institutt for statsvitenskap og Dag Henrik Tuastad ved Institutt for kulturstudier og orientalske språk, for solid veiledning, og stor tålmodighet når det gjelder å følge opp arbeidet mitt. Jeg vil også takke As’ad Ghanem ved Universitetet i Haifa, Abeer Baker i menneskerettighetsorganisasjonen Adalah og Jaffar Farah i organisasjonen Mossawa for å ha gitt meg store mengder materiale om Palestinere i Israel. Dessuten vil jeg takke min palestinske venninne Nadia Haj Yasein og hennes familie i Jerusalem for å ha latt meg bo hos dem under store deler av feltarbeidet i desember 2006. Tusen takk for gjestfriheten. Videre vil jeg takke min mann Tariq for gode diskusjoner, nyttige innspill og tålmodigheten han har vist gjennom hele prosessen. Jeg vil også takke mine venninner Ida Martinuessen, Kjersti Olsen og Anniken Westtorp, som har bidratt med kommentarer og korrekturlesning. Til sist, men ikke minst vil jeg takke mine foreldre, mine søsken og min familie i Palestina for oppmuntring og støtte hele veien. Oslo, mai 2007 Gada Ezat Azam 3 Innhold FORORD...............................................................................................................................................2 -

Saxony: Landscapes/Rivers and Lakes/Climate

Freistaat Sachsen State Chancellery Message and Greeting ................................................................................................................................................. 2 State and People Delightful Saxony: Landscapes/Rivers and Lakes/Climate ......................................................................................... 5 The Saxons – A people unto themselves: Spatial distribution/Population structure/Religion .......................... 7 The Sorbs – Much more than folklore ............................................................................................................ 11 Then and Now Saxony makes history: From early days to the modern era ..................................................................................... 13 Tabular Overview ........................................................................................................................................................ 17 Constitution and Legislature Saxony in fine constitutional shape: Saxony as Free State/Constitution/Coat of arms/Flag/Anthem ....................... 21 Saxony’s strong forces: State assembly/Political parties/Associations/Civic commitment ..................................... 23 Administrations and Politics Saxony’s lean administration: Prime minister, ministries/State administration/ State budget/Local government/E-government/Simplification of the law ............................................................................... 29 Saxony in Europe and in the world: Federalism/Europe/International -

Palestinian Citizens of Israel: Agenda for Change Hashem Mawlawi

Palestinian Citizens of Israel: Agenda for Change Hashem Mawlawi Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master‘s degree in Conflict Studies School of Conflict Studies Faculty of Human Sciences Saint Paul University © Hashem Mawlawi, Ottawa, Canada, 2019 PALESTINIAN CITIZENS OF ISRAEL: AGENDA FOR CHANGE ii Abstract The State of Israel was established amid historic trauma experienced by both Jewish and Palestinian Arab people. These traumas included the repeated invasion of Palestine by various empires/countries, and the Jewish experience of anti-Semitism and the Holocaust. This culminated in the 1948 creation of the State of Israel. The newfound State has experienced turmoil since its inception as both identities clashed. The majority-minority power imbalance resulted in inequalities and discrimination against the Palestinian Citizens of Israel (PCI). Discussion of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict tends to assume that the issues of the PCIs are the same as the issues of the Palestinians in the Occupied Territories. I believe that the needs of the PCIs are different. Therefore, I have conducted a qualitative case study into possible ways the relationship between the PCIs and the State of Israel shall be improved. To this end, I provide a brief review of the history of the conflict. I explore themes of inequalities and models for change. I analyze the implications of the theories for PCIs and Israelis in the political, social, and economic dimensions. From all these dimensions, I identify opportunities for change. In proposing an ―Agenda for Change,‖ it is my sincere hope that addressing the context of the Israeli-Palestinian relationship may lead to a change in attitude and behaviour that will avoid perpetuating the conflict and its human costs on both sides. -

General Observations About the Free State Provincial Government

A Better Life for All? Fifteen Year Review of the Free State Provincial Government Prepared for the Free State Provincial Government by the Democracy and Governance Programme (D&G) of the Human Sciences Research Council. Ivor Chipkin Joseph M Kivilu Peliwe Mnguni Geoffrey Modisha Vino Naidoo Mcebisi Ndletyana Susan Sedumedi Table of Contents General Observations about the Free State Provincial Government........................................4 Methodological Approach..........................................................................................................9 Research Limitations..........................................................................................................10 Generic Methodological Observations...............................................................................10 Understanding of the Mandate...........................................................................................10 Social attitudes survey............................................................................................................12 Sampling............................................................................................................................12 Development of Questionnaire...........................................................................................12 Data collection....................................................................................................................12 Description of the realised sample.....................................................................................12 -

The Archaeology of the Prussian Crusade

Downloaded by [University of Wisconsin - Madison] at 05:00 18 January 2017 THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE PRUSSIAN CRUSADE The Archaeology of the Prussian Crusade explores the archaeology and material culture of the Crusade against the Prussian tribes in the thirteenth century, and the subsequent society created by the Teutonic Order that lasted into the six- teenth century. It provides the first synthesis of the material culture of a unique crusading society created in the south-eastern Baltic region over the course of the thirteenth century. It encompasses the full range of archaeological data, from standing buildings through to artefacts and ecofacts, integrated with writ- ten and artistic sources. The work is sub-divided into broadly chronological themes, beginning with a historical outline, exploring the settlements, castles, towns and landscapes of the Teutonic Order’s theocratic state and concluding with the role of the reconstructed and ruined monuments of medieval Prussia in the modern world in the context of modern Polish culture. This is the first work on the archaeology of medieval Prussia in any lan- guage, and is intended as a comprehensive introduction to a period and area of growing interest. This book represents an important contribution to promot- ing international awareness of the cultural heritage of the Baltic region, which has been rapidly increasing over the last few decades. Aleksander Pluskowski is a lecturer in Medieval Archaeology at the University of Reading. Downloaded by [University of Wisconsin - Madison] at 05:00 -

9 Purple 18/2

THE CONCORD REVIEW 223 A VERY PURPLE-XING CODE Michael Cohen Groups cannot work together without communication between them. In wartime, it is critical that correspondence between the groups, or nations in the case of World War II, be concealed from the eyes of the enemy. This necessity leads nations to develop codes to hide their messages’ meanings from unwanted recipients. Among the many codes used in World War II, none has achieved a higher level of fame than Japan’s Purple code, or rather the code that Japan’s Purple machine produced. The breaking of this code helped the Allied forces to defeat their enemies in World War II in the Pacific by providing them with critical information. The code was more intricate than any other coding system invented before modern computers. Using codebreaking strategy from previous war codes, the U.S. was able to crack the Purple code. Unfortunately, the U.S. could not use its newfound knowl- edge to prevent the attack at Pearl Harbor. It took a Herculean feat of American intellect to break Purple. It was dramatically intro- duced to Congress in the Congressional hearing into the Pearl Harbor disaster.1 In the ensuing years, it was discovered that the deciphering of the Purple Code affected the course of the Pacific war in more ways than one. For instance, it turned out that before the Americans had dropped nuclear bombs on Japan, Purple Michael Cohen is a Senior at the Commonwealth School in Boston, Massachusetts, where he wrote this paper for Tom Harsanyi’s United States History course in the 2006/2007 academic year.