SIR EDMUND WALKER, SERVANT of CANADA By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EVERDON BUREAU DE CHANGE Corporate Profile Design

Fast, Safe & Convenient Currency Exchange CORPORATE BROCHURE We take pride in exceeding our clients’ expectations by providing foreign exchange services using a wide array of innovative solutions. 2 We take pride in exceeding our client's expectations by providing foreign exchange services using a wide array of innovative solutions 3 EVERDON BUREAU DE CHANGE is a Dun & Bradstreet convenience ensured to keep your business. We maintain certified foreign exchange company headquartered at long-term strategic relationships with retailers, travel Foresight House, 163/165 Broad Street, Marina, Lagos, agents, major corporate and financial institutions to Nigeria. Everdon Bureau de Change was incorporated and provide them with retail foreign exchange and brokerage commenced operations in June 2014. solutions. We are a subsidiary of VFD Group Plc, a financial services Everdon BDC is an authorised dealer for Personal Travel focused proprietary investment company. Everdon Bureau Allowance (PTA) and Business Travel Allowance (BTA). We de Change constitutes a part of the Group's financial also provide solutions to a range of business partners in service solutions chain and specialises in providing offering foreign currency services to their customers. Our currency exchange services to individuals and corporates. services include rate advisory, forex sales and purchase, and we cater for a robust customer base monthly. We believe that exceptional service delivery and performance are essential to our clients’ satisfaction. We also understand that your trust must be earned, and 4 OUR FOCUS We are fashioned around our clients’ need for speed and convenience. Our innovative business approach enables us to render services at a physical location and via digital platforms. -

2020 a Sentimental Journey

0 1 3 Lifescapes is a writing program created to help people tell their life stories, to provide support and guidance for beginner and experienced writers alike. This year marks our thirteenth year running the program at the Brantford Public Library, and A Sentimental Journey is our thirteenth collection of stories to be published. On behalf of Brantford Public Library and this year’s participants, I would like to thank lead instructor Lorie Lee Steiner and editor Shailyn Harris for their hard work and dedication to bringing this anthology to completion. Creating an anthology during a pandemic has been a truly unprecedented experience for everyone involved. Beyond the stress and uncertainty of facing a global contagion, our writers lost the peer support of regular meetings and access to resources. Still, many persevered with their writing, and it is with considerable pride and triumph that I can share the resulting collection of memories and inspiration with you. I know that many of us will look back at 2020 and remember the hardship, the fear, and the loss. It is more important than ever to remember that we – both individually and as a society – have persevered through hard times before, and we will persevere through these times as well. As you read their stories, be prepared to feel both the nostalgia of youth and the triumph of overcoming past adversity. Perhaps you will remember your own childhood memories of travelling with your family, or marvel at how unexpected encounters with interesting people can change perspective and provide insight … and sometimes, change the course of a life. -

2019-26 Financial Services

2019-26 Financial Services Subsidiary Legislation made under ss.6(1), 24(3)(v), 44(4), 61(1), 63(3), 64(3), 150(1), 164(1),166(2), 620(1), 621(1) and 627. FINANCIAL SERVICES (BUREAUX DE CHANGE) REGULATIONS 2020 LN.2020/008 Commencement 15.1.2020 _______________________ ARRANGEMENT OF REGULATIONS. Regulation PART 1 PRELIMINARY 1. Title and Commencement. 2. Interpretation. 3. Application. PART 2 CONDUCT OF BUSINESS Independence 4. Independence. 5. Material interest. 6. Inducements. Advertising and marketing 7. Issue of advertisements. 8. Identification of advertisement issuer. 9. Fair and clear communications. 10. Customer’s understanding of risk. 11. Information about the bureau. 12. Representatives of the bureau. Customer relations 13. Customer agreements. © Government of Gibraltar (www.gibraltarlaws.gov.gi) 2019-26 Financial Services FINANCIAL SERVICES (BUREAUX DE CHANGE) 2020/008 REGULATIONS 2020 14. When written customer agreement required. 15. Customer’s rights. 16. Suitability. 17. Charges. Administration 18. Complaints. 19. Compliance. 20. Supervision. 21. Cessation of business. PART 3 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE AND RISK MANAGEMENT Accounting records 22. Duty to keep accounting records. 23. Reconciliation of customer money. 24. Records to be kept up to date. 25. Audit trail. 26. Conformity with accounting standards. 27. Retention of records. 28. Inspection of records. PART 4 PRUDENTIAL REQUIREMENTS Financial statements 29. Duty to prepare financial statements. 30. Balance sheet to give true and fair view. 31. Profit and loss account to give true and fair view. 32. Form and content of financial statements. 33. Annual financial statements to be submitted to meeting of partners, etc. 34. Additional requirement in case of sole proprietor. -

Economic Bulletin for the Quarter Ending June, 2010 Vol. Xlii No. 2

BANK OF TANZANIA ECONOMIC BULLETIN FOR THE QUARTER ENDING JUNE, 2010 VOL. XLII NO. 2 For any enquiries contact: Directorate of Economic Research and Policy Bank of Tanzania, P.O. Box 2939, Dar es Salaam Tel: +255 (22) 2233328, Fax: +255 (22) 2234060 http://www.bot-tz.org TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY OF ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS .................................................................................. 3 Food Supply Situation ........................................................................................................................... 6 Inflation Developments ......................................................................................................................... 7 2.0 MONETARY AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS ...................................................................... 9 Money and Credit ................................................................................................................................. 9 Interest Rate Developments .................................................................................................................10 Financial Market Operations ...............................................................................................................11 Foreign Exchange Market Operations .................................................................................................13 Bureau de Change Operations .............................................................................................................14 3.0 PUBLIC FINANCE .............................................................................................................................15 -

Bureau De Change Guidelines.Pdf

CENTRAL BANK OF SEYCHELLES INFORMATION ON THE ESTABLISHMENT AND OPERATIONS OF LICENCED BUREAUX DE CHANGE IN SEYCHELLES 1. Regulatory Framework The Central Bank of Seychelles (CBS) is the regulator of Bureaux de Change businesses, governed by the Financial Institutions Act 2004 and the Financial Institutions (Bureau de Change) Regulations 2008. Furthermore, Bureaux de Change need to adhere to the requirements of the Anti-Money Laundering (AML) Act 2006, AML (Amendment) Act 2008 and Prevention of Terrorism Act 2004, administered by the Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU). These guidelines set out the requirements for prospective applicants of a Bureau de Change licence as per the provisions contained in the above-mentioned Act and Regulations. 2. Definition of Bureau de Change A Bureau de Change shall be construed as any company incorporated under the Companies Act 1972 or a branch of a foreign company, registered under the local Companies Act, licenced to solely carry out foreign exchange business. 3. Types of Bureaux de Change licences CBS grants two types of Bureaux de Change licences: a. “Class A” Bureau de Change is licenced to buy and sell foreign currency without the limitation that applies to “Class B” Bureau de Change e.g. it could engage in money transmission services; and b. “Class B” Bureau de Change is restricted to buying and selling foreign currency only in the form of notes, coins and travelers cheques. 4. Application Forms Separate application forms are available for “Class A” and “Class B” applicants; the latter being more straightforward than the former given that the holder of a “Class B” Bureau de Change licence engages in relatively simpler activities. -

Forced Segregation of Black Students in Canada West Public Schools and Myths of British Egalitarianism

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — “We had no desire to be set apart”: Forced Segregation of Black Students in Canada West Public Schools and Myths of British Egalitarianism KRISTIN McLAREN* The practice of school segregation in mid-nineteenth-century Canada West defied popular images of the province as a guardian of British moral and egalitarian ideals. African Canadians in Canada West found themselves excluded from public education or forced into segregation, practices that were against the spirit if not the letter of British and Canadian law. Education laws were changed to accommodate racism, while guardians of the education system tolerated illegal discriminatory practices. A number of historians have described the emergence of segregated racial schools in Canada West as a response to requests by black people to be sepa- rate; however, historical evidence contradicts this assertion. African Canadians in the mid-nineteenth century fought against segregation and refused to be set apart. Numerous petitions to the Education Department complained of exclusion from common schools and expressed desires for integration, not segregation. When black people did open their own schools, children of all ethnic backgrounds were welcome in these institutions. La politique de ségrégation scolaire que l’on pratiquait dans l’Ouest canadien du milieu du XIXe siècle contredit l’image populaire de gardienne des idéaux moraux et égalitaires britanniques que l’on se faisait de la province. Les Afro-Canadiens de l’Ouest canadien étaient privés d’enseignement public ou ségrégués, des pratiques qui allaient à l’encontre de l’esprit sinon de la lettre du droit britannique et cana- dien. Les lois sur l’enseignement ont été modifiées pour laisser place au racisme, tandis que les gardiens du système d’éducation toléraient des pratiques discrimina- toires illicites. -

Ll HERITAGE Mrn~•Ll PATRIMOINE

• El ONTARIO • ESFIDUCIE DU mm !•ll HERITAGE mrn ~•ll PATRIMOINE lll• d TRUST lll• d ONTARIEN An agency of the Government of Ontario Un organisme du gouvernement de !'Ontario This document was retrieved from the Ontario Heritage Act e-Register, which is accessible through the website of the Ontario Heritage Trust at www.heritagetrust.on.ca. Ce document est tiré du registre électronique. tenu aux fins de la Loi sur le patrimoine de l’Ontario, accessible à partir du site Web de la Fiducie du patrimoine ontarien sur www.heritagetrust.on.ca. • I BYLAW NO. 182-2005 -of- THE CORPORATION OF THE CITY OF BRANTFORD A Bylaw to designate the Bell Memorial as having cultural heritage value or interest, and to repeal Bylaw 132-2005 WHEREAS Section 29 of the Ontario Heritage Act, Chapter 0.18, R.S.O. 1990, authorizes the Council of a municipality to enact bylaws to designate real property, including all of the buildings or structures thereon, to be of cultural heritage value or interest; AND WHEREAS the Council of the Corporation of the City of Brantford, on the recommendation of the Brantford Heritage Committee, has carried out the required Notice of Intention to Designate the Bell Memorial: AND WHEREAS no notice of objection to the said designation has been served upon the Clerk of the Municipality; NOW THEREFORE THE COUNCIL OF THE CORPORATION OF THE CITY OF BRANTFORD ENACTS AS FOLLOWS: 1. THAT there is designated as being of cultural heritage value the real property known as Bell Memorial in the City of Brantford, as described in Schedule 'B' attached hereto and forming part of this Bylaw; 2. -

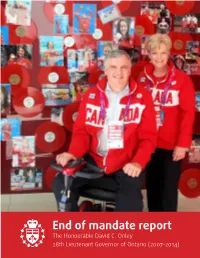

Mr. Onley's End of Mandate Report

End of mandate report The Honourable David C. Onley 28th Lieutenant Governor of Ontario (2007–2014) His Honour the Honourable David C. Onley, OOnt 28th Lieutenant Governor of Ontario Shown in the uniform of Colonel of the Regiment of The Queen’s York Rangers (1st American Regiment) Painted by Juan Martínez ii End of mandate report: The Hon. David C. Onley (2007–2014) Table of contents At a glance 2 Community role 14–17 The Queen’s Diamond Jubilee 24–25 14 Youth and education Introductory messages 3 Science 24 Medal presentations 3 Lieutenant Governor 15 Arts and culture 60 in 60 Chief of Staff 16 Sports and recreation Royal visit 17 Volunteer service organizations Diamond Jubilee Galas Biographies 4–5 Faith communities Honours and awards 26–27 4 His Honour Northern Ontario tour 26 Order of Ontario 5 Her Honour His Honour honoured Ontario honours Constitutional Representational and Ontario awards responsibilities 6 celebratory role 18–23 Lieutenant Governor’s Awards 6 Representing the head of state 18 Welcoming visitors 27 Awards programs supported Powers and responsibilities 19 Representing Ontarians abroad by the Lieutenant Governor 20 Celebrating milestones Core initiatives 7–11 Office operations 28 21 Leading commemorations 7 Accessibility 28 Federal funding Celebrating citizenship 10 Aboriginal peoples in Ontario Provincial funding 22 Uniformed services Connecting with Appendix 29 Ontarians 12–13 29 Groups holding viceregal 12 Engaging Ontarians online patronage Traditional communications 13 Spending time with Ontarians Since 1937, the Lieutenant Governor of Ontario operates out of a suite of offices located in the northwest corner of the Legislative Building at Queen’s Park 1 At a glance Highlights of Mr. -

This Document Was Retrieved from the Ontario Heritage Act E-Register, Which Is Accessible Through the Website of the Ontario Heritage Trust At

This document was retrieved from the Ontario Heritage Act e-Register, which is accessible through the website of the Ontario Heritage Trust at www.heritagetrust.on.ca. Ce document est tiré du registre électronique. tenu aux fins de la Loi sur le patrimoine de l’Ontario, accessible à partir du site Web de la Fiducie du patrimoine ontarien sur www.heritagetrust.on.ca. l~;-&~i ONTARIO HERIT.A:GE;; TRUSf /], /1,li) # If ]-Uff{ BYLAW NO. 132-2005 1 -o.f- c:T 3 1 2019 ;-.. ,... - -~, 'EDTlffi CORPORATION OF THE C.lTY OF BRANTFORD RE· ·· L, CI V ~ Bylaw to designate the Bell Memorial as having cultural heritage value or interest. WHEREAS Section 29 of the Ontario Heritage Act, Chapter 0.18, R.S.O. 1990, authorizes the Council of a municipality to enact bylaws to designate real property, including all of the buildings or structures thereon, to be of cultural heritage value or interest; AND WHEREAS the Council of the Corporation of the City of Brantford, on the recommendation of the Brantford Heritage Committee, has carried out the required Notice of Intention to Designate Bell memorial Park; AND \VHEREAS no notice ofobjection to the said designation has been served upon the Clerk of the Municipality; NOW THEREFORE THE COUNCIL OF THE CORPORATION OF THE CITY OF BRANTFORD ENACTS AS FOLLOWS: I. THAT there is designated as being of cultural heritage value the real property known as Bell Memorial in the City of Brantford, as described in Schedule 'B' attached hereto and fotming part of this Bylaw; 2. THAT the City Solicitor is hereby authorized to cause a copy of the Bylaw to be registered against the property described in Schedule 'A' attached hereto in the proper land registry office; 3. -

Groups Rally to Help Detroit 3

20081208-NEWS--0001-NAT-CCI-CD_-- 12/5/2008 6:44 PM Page 1 ® www.crainsdetroit.com Vol. 24, No. 49 DECEMBER 8 – 14, 2008 $2 a copy; $59 a year ©Entire contents copyright 2008 by Crain Communications Inc. All rights reserved THIS JUST IN AAA gives MGM Grand a Mortgage rates pair of 4-diamond ratings MGM Grand Detroit has earned two top honors in the hospitality industry, winning a pair of Four Dia- mond awards from Heathrow, Fla.-based AAA. dip, then ‘boom’ It marks the first proper- ty in Detroit to get the award for both a restau- rant and a hotel, winning Brokers beat drum; blitz of MORTGAGE RATE DROP for the 400-room hotel and Ⅲ What happened: During the the Saltwater restaurant. refinancing may save year week ending Nov. 28, the John Hutar, vice president national average for 30-year, of hotel operations, said he fixed-rate mortgages dropped to BY DANIEL DUGGAN the hole, said Brian Siebert, requested that AAA con- 5.47 percent from 5.99 percent CRAIN’S DETROIT BUSINESS president of Waterford Town- sider the hotel and Saltwa- the week before. ship-based Watson Financial ter two months after the Ⅲ What caused the drop: The The battered mortgage bro- Group. property Federal Reserve Board’s kers who’ve spent the last “We’ve had a few really opened last announcement to pledge $500 year under the dark cloud of a good days,” he said. “But November. billion for the purchase of credit crunch found a bright we’re still down 70 percent “For NATHAN SKID/CRAIN’S DETROIT BUSINESS mortgage-backed debt and $100 spot just before Thanksgiving from two years ago.” hoteliers, Ronnie Jamil, co-owner, Bella Vino Fine Wine billion for loans from Freddie when interest rates dropped Nonetheless, brokers aim to Mac and Fannie Mae. -

Uot History Freidland.Pdf

Notes for The University of Toronto A History Martin L. Friedland UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS Toronto Buffalo London © University of Toronto Press Incorporated 2002 Toronto Buffalo London Printed in Canada ISBN 0-8020-8526-1 National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data Friedland, M.L. (Martin Lawrence), 1932– Notes for The University of Toronto : a history ISBN 0-8020-8526-1 1. University of Toronto – History – Bibliography. I. Title. LE3.T52F75 2002 Suppl. 378.7139’541 C2002-900419-5 University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial assistance to its publishing program of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council. This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Humanities and Social Sciences Federation of Canada, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. University of Toronto Press acknowledges the finacial support for its publishing activities of the Government of Canada, through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP). Contents CHAPTER 1 – 1826 – A CHARTER FOR KING’S COLLEGE ..... ............................................. 7 CHAPTER 2 – 1842 – LAYING THE CORNERSTONE ..... ..................................................... 13 CHAPTER 3 – 1849 – THE CREATION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO AND TRINITY COLLEGE ............................................................................................... 19 CHAPTER 4 – 1850 – STARTING OVER ..... .......................................................................... -

Proquest Dissertations

A STUDY OP THE RYEESON-CHAEBOMEL CONTROVERSY AND ITS BACKGROUND by Joseph Jean-Guy Lajoie Thesis presented to the Department of Religious Studies of the Faculty of Arts of the University of Ottawa as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts tttltitf . LIBRARIIS » Ottawa, Canada, 1971 UMI Number: EC56186 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI UMI Microform EC56186 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis was prepared under the supervision of Professor R. Choquette, B.A. (Pol. Sc), B.Th., M.Th., S.T.L., M.A. (Chicago), of the Department of Religious Studies of the Faculty of Arts of the University of Ottawa. CURRICULUM STUDIORUM Joseph Jean-Guy Lajoie was born February 8, 1942, in Timmins, Ontario, Canada. He received his B.A. from the University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, in 1964. TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter page INTRODUCTION vi I.- REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE 1 Contemporary Literature 1 Subsequent Literature 9 IT.- HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 21 Development of Education in Upper Canada, 1797-1840 21 Development of Religion in Upper Canada, 1797-1849 24 Development of Education in Upper Canada, 1841-1849 36 III.- THE RYERSON CHARBONNEL CONTROVERSY 47 SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS 64 BIBLIOGRAPHY 66 Appendix 1.