Politics in Digital Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdf Dokument

Udskriftsdato: 2. oktober 2021 2017/1 BTB 91 (Gældende) Betænkning over Forslag til folketingsbeslutning om en uvildig undersøgelse af udlændinge og integrationsministerens håndtering af adskilt indkvartering af mindreårige gifte eller samlevende asylansøgere Ministerium: Folketinget Betænkning afgivet af Udvalget for Forretningsordenen den 23. maj 2018 Betænkning over Forslag til folketingsbeslutning om en uvildig undersøgelse af udlændinge- og integrationsministerens håndtering af adskilt indkvartering af mindreårige gifte eller samlevende asylansøgere [af Mattias Tesfaye (S), Nikolaj Villumsen (EL), Josephine Fock (ALT), Sofie Carsten Nielsen (RV) og Holger K. Nielsen (SF)] 1. Udvalgsarbejdet Beslutningsforslaget blev fremsat den 14. marts 2018 og var til 1. behandling den 26. april 2018. Be- slutningsforslaget blev efter 1. behandling henvist til behandling i Udvalget for Forretningsordenen. Møder Udvalget har behandlet beslutningsforslaget i 2 møder. 2. Indstillinger og politiske bemærkninger Et flertal i udvalget (DF, V, LA og KF) indstiller beslutningsforslaget til forkastelse. Flertallet konstaterer, at sagen om udlændinge- og integrationsministerens håndtering af adskilt ind- kvartering af mindreårige gifte eller samlevende asylansøgere er blevet diskuteret i mange, lange samråd, og at sagen derfor er belyst. Flertallet konstaterer samtidig, at ministeren flere gange har redegjort for forløbet. Det er sket både skriftligt og mundtligt. Flertallet konstaterer også, at den kritik, som Folketingets Ombudsmand rettede mod forløbet i 2017, er en kritik, som udlændinge- og integrationsministeren har taget til efterretning. Det gælder både kritikken af selve ordlyden i pressemeddelelsen og kritikken af, at pressemeddelelsen medførte en risiko for forkerte afgørelser. Flertallet mener, at det afgørende har været, at der blev lagt en så restriktiv linje som muligt. For flertallet ønsker at beskytte pigerne bedst muligt, og flertallet ønsker at bekæmpe skikken med barnebru- de. -

Den Muslimske Stemmeguide 2015

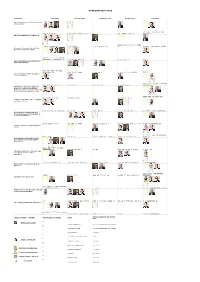

Den Muslimske Stemmeguide 2015 Denne stemmeguide er lavet som service til muslimske vælgere til folketingsvalget i 2015. Guiden tilsigter at skabe et overblik over folketingskandidaternes holdning til emner, der har en særlig interesse for muslimske borgere i Danmark. Det er ikke guidens formål til at fremme bestemte kandidater eller partier, men hensigten er at gøre det nemmere, så man som vælger på kort tid kan skabe sig et overblik over kandidaterne i ens egen storkreds. På den måde ønsker vi at hjælpe muslimske vælgere med at træffe et mere politisk bevidst valg, når de vælger at afgive deres stemme. De grafiske fremstillinger i guiden viser, hvilke holdninger er mest udbredte i hvert parti og giver et samlet billede af, hvordan alle opstillede kandidater placerer sig på de enkelte spørgsmål. Listen er primært udarbejdet på baggrund af valgtesten på netavisen 180grader, som er en borgerlig-liberal netavis, samt valgtesten fra DR. Vær opmærksom på, at listen over politikere ikke er udtømmende, da det ikke er alle opstillede kandidater, som har deltaget i begge valgtests. Kandidater, der ikke har deltaget i testen på 180grader er blevet frasorteret, da alle undtaget et enkelt udsagn er hentet fra dem. Kandidater opstillet udenfor partier medvirker ikke. Sådan bruges guiden I listen over storkredse, skal du vælge storkredsen, hvor du har bopæl i og er stemmeberettiget. Her vil du finde en liste over de opstillede kandidater inddelt efter partier samt deres standpunkter til en række udsagn. Du kan også få et overblik over, hvilke holdninger er mest udbredte hos hvert parti samt på tværs af partierne, ved at se på listen over diagrammer. -

Kandidattest Fv15

KANDIDATTEST FV15 SPØRGSMÅL HELT UENIG DELVIST UENIG HVERKEN/ELLER DELVIST ENIG HELT ENIG Efter folkeskolereformen får eleverne for lange skoledage CCCC IIIIII KKKKKKKKKK OOO AAA B F O VVVVVV AAAAA BBB C FFFFF O VV O B C I OOOO V ØØ ÅÅ ØØØØØØØ Å Afgiften på cigaretter skal sættes op AAAAA B CC F KKK O V ØØØØ C IIIIII K OOOOO VV F I O VVVVV A B C KK O V ØØ Å AA BBB CC FFFF KKKK O ØØØ ÅÅ Et besøg hos den praktiserende læge skal koste eksempelvis 100 kr. AAAAAAA CCCC FFFFFF KKKKKK OOOOOOOO V ØØØØØØØØØ ÅÅ A BB C KKK OO VVVV C V B II K VVV Å BB IIIII Mere af ældreplejen skal udliciteres til private virksomheder AAAA BB FFFFFF KKK OOO ØØØØØØØØØ ÅÅ AAAA BB KKK OOOO C KKK OO Å B CCCCC I K O VVVVVVVV IIIIII V Man skal hurtigere kunne genoptjene retten til dagpenge AAAAA B FFFFFF KKKKKK OOOOOOO BBB CCCC IIIIIII K VV CC O VVV AA B K O VV A KK OO VV Å ØØØØØØØØØ ÅÅ Virksomheder skal kunne drages til ansvar for, om deres udenlandske underleverandører i Danmark overholder danske regler om løn, moms og skat AAAAA BBB CC FFFFFF KKK B CC IIIIIII KK O VVV A C KKK O VVVV C O AA B KK O VV Å OOOOOO ØØØØØØØØØ ÅÅ Vækst i den offentlige sektor er vigtigere end skattelettelser B CCCCCC IIIIIII O VVVVVVVVV BB KK OO KKKK OO ÅÅ AAAAAA BB KKK OO Å AA FFFFFF K OOO ØØØØØØØØØ Investeringer i kollektiv trafik skal prioriteres højere end investeringer til fordel for privatbilisme III KK OOOOO VVV Ø CCC IIII OO VVVV AAA BB CC KKKK O V AAA BB C FFF KKKK O V Ø Å AA FFF O ØØØØØØØ ÅÅ Straffen for grov vold og voldtægt skal skærpes CCCC IIIIIII KKKK OOOOOOOOOO BBB F ØØØ A B -

Opskriften På Succes Stort Tema Om Det Nye Politiske Landkort

UDGAVE NR. 5 EFTERÅR 2016 Uffe og Anders Opskriften på succes Stort tema om det nye politiske landkort MAGTDUO: Metal-bossen PORTRÆT: Kom tæt på SKIPPER: Enhedslistens & DI-direktøren Dansk Flygtningehjælps revolutionære kontrolfreak topchef www.mercuriurval.dk Ledere i bevægelse Ledelse i balance Offentlig ledelse + 150 85 250 toplederansættelser konsulenter over ledervurderinger og i den offentlige sektor hele landet udviklingsforløb på over de sidste tre år alle niveauer hvert år Kontakt os på [email protected] eller ring til os på 3945 6500 Fordi mennesker betyder alt EFTERÅR 2016 INDHOLD FORDOMME Levebrød, topstyring og superkræfter 8 PORTRÆT Skipper: Enhedslistens nye profil 12 NYBRUD Klassens nye drenge Anders Samuelsen og Uffe Elbæk giver opskriften på at lave et nyt parti. 16 PARTIER Nyt politisk kompas Hvordan ser den politiske skala ud i dag? 22 PORTRÆT CEO for flygningehjælpen A/S Kom tæt på to-meter-manden Andreas Kamm, som har vendt Dansk Flygtningehjælp fra krise til succes. 28 16 CIVILSAMFUND Danskerne vil hellere give gaver end arbejde frivilligt 34 TOPDUO Spydspidserne 52 Metal-bossen Claus Jensen og DI-direktøren Karsten Dybvad udgør et umage, men magtfuldt par. 40 INDERKREDS Topforhandlerne Mød efterårets centrale politikere. 44 INTERVIEW Karsten Lauritzen: Danmark efter Brexit 52 BAGGRUND Den blinde mand og 12 kampen mod kommunerne 58 KLUMME Klumme: Jens Christian Grøndahl 65 3 ∫magasin Efterår 2016 © �∫magasin er udgivet af netavisen Altinget ANSVARSHAVENDE CHEFREDAKTØR Rasmus Nielsen MAGASINREDAKTØR Mads Bang REDAKTION Anders Jerking Erik Holstein Morten Øyen Jensen Klaus Ulrik Mortensen Kasper Frandsen Mads Bang Hjalte Kragesteen Sine Riis Lund Kim Rosenkilde Rikke Albrechtsen Anne Justesen Frederik Tillitz Erik Bjørn Møller Toke Gade Crone Kristiansen Søren Elkrog Friis Emma Qvirin Holst Carsten Terp Rasmus Løppenthin Amalie Bjerre Christensen Tyson W. -

University of Copenhagen FACULTY of SOCIAL SCIENCES Faculty of Social Sciences UNIVERSITY of COPENHAGEN · DENMARK PHD DISSERTATION 2019 · ISBN 978-87-7209-312-3

Arctic identity interactions Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s and Denmark’s foreign policies Jacobsen, Marc Publication date: 2019 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (APA): Jacobsen, M. (2019). Arctic identity interactions: Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s and Denmark’s foreign policies. Download date: 11. okt.. 2021 DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE university of copenhagen FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES faculty of social sciences UNIVERSITY OF COPENHAGEN · DENMARK PHD DISSERTATION 2019 · ISBN 978-87-7209-312-3 MARC JACOBSEN Arctic identity interactions Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s and Denmark’s foreign policies Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s and Denmark’s foreign policies and Denmark’s Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s identity interactions Arctic Arctic identity interactions Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s and Denmark’s foreign policies PhD Dissertation 2019 Marc Jacobsen DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE university of copenhagen FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES faculty of social sciences UNIVERSITY OF COPENHAGEN · DENMARK PHD DISSERTATION 2019 · ISBN 978-87-7209-312-3 MARC JACOBSEN Arctic identity interactions Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s and Denmark’s foreign policies Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s and Denmark’s foreign policies and Denmark’s Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s identity interactions Arctic Arctic identity interactions Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s and Denmark’s foreign policies PhD Dissertation 2019 Marc Jacobsen Arctic identity interactions Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s and Denmark’s foreign policies Marc Jacobsen PhD Dissertation Department of Political Science University of Copenhagen September 2019 Main supervisor: Professor Ole Wæver, University of Copenhagen. Co-supervisor: Associate Professor Ulrik Pram Gad, Aalborg University. -

The Nordic Countries and the European Security and Defence Policy

bailes_hb.qxd 21/3/06 2:14 pm Page 1 Alyson J. K. Bailes (United Kingdom) is A special feature of Europe’s Nordic region the Director of SIPRI. She has served in the is that only one of its states has joined both British Diplomatic Service, most recently as the European Union and NATO. Nordic British Ambassador to Finland. She spent countries also share a certain distrust of several periods on detachment outside the B Recent and forthcoming SIPRI books from Oxford University Press A approaches to security that rely too much service, including two academic sabbaticals, A N on force or that may disrupt the logic and I a two-year period with the British Ministry of D SIPRI Yearbook 2005: L liberties of civil society. Impacting on this Defence, and assignments to the European E Armaments, Disarmament and International Security S environment, the EU’s decision in 1999 to S Union and the Western European Union. U THE NORDIC develop its own military capacities for crisis , She has published extensively in international N Budgeting for the Military Sector in Africa: H management—taken together with other journals on politico-military affairs, European D The Processes and Mechanisms of Control E integration and Central European affairs as E ongoing shifts in Western security agendas Edited by Wuyi Omitoogun and Eboe Hutchful R L and in USA–Europe relations—has created well as on Chinese foreign policy. Her most O I COUNTRIES AND U complex challenges for Nordic policy recent SIPRI publication is The European Europe and Iran: Perspectives on Non-proliferation L S Security Strategy: An Evolutionary History, Edited by Shannon N. -

Folketingsbeslutning Om Et Dansk Militært Bidrag Til En Multinational Indsats I Mellemøsten"

Forhandling i Folketinget om beslutningsforslag nr. B 114: "Forslag til folketingsbeslutning om et dansk militært bidrag til en multinational indsats i Mellemøsten" Første behandling tirsdag 17 februar 1998 Teksten ligger i RTF-format Downloadet fra "Fred på Nettet" OnLine Biblioteket - FRED.dk/biblion/ "OnLine Biblioteket" i Fred på Nettet er startet af Aldrig Mere Krig ved Tom Vilmer Paamand og Holger Terp Kommentarer sendes til [email protected] B 114 (som fremsat): Forslag til folketingsbeslutning om et dansk militært bidrag til en multinational indsats i Mellemøsten. Folketinget giver sit samtykke til et dansk militært bidrag til en multinational indsats i Mellemøsten. Det danske militære bidrag skal medvirke til at sikre Iraks efterlevelse af sine forpligtelser i henhold til FNs sikkerhedsrådsresolution 687 af 3. april 1991. Bemærkninger til forslaget I. Den 3. april 1991 vedtog FNs Sikkerhedsråd resolution 687 om våbenhvilen mellem Irak og Kuwait og de FN-medlemslande, der samarbejdede med Kuwait i henhold til resolution 678 af 29. november 1990. Resolution 678, som gav mandat til angrebet på Irak i 1991, bemyndigede i henhold til FN Pagtens kapitel VII disse lande til at anvende alle nødvendige midler til at genoprette international fred og sikkerhed i området. Resolution 687 bekræfter gyldigheden af de tidligere vedtagne resolutioner om krisen, herunder resolution 678. Resolution 687 gør våbenhvilen mellem de FN-medlemslande, der samarbejdede med Kuwait på den ene side og Irak på den anden side betinget af, at Irak lever op til en række krav, herunder om brug, udvikling og tilintetgørelse af masseødelæggelsesvåben. UNSCOM (United Nations Special Commission) blev oprettet til at gennemføre inspektioner af Iraks kapaciteter på de biologiske og kemiske områder og f.s.v.a. -

En Kortlægning Af Debatten Om Corona I Mediers Og Politikeres Kommentarspor På Facebook

Krig og kærlighed i coronaens tid En kortlægning af debatten om corona i mediers og politikeres kommentarspor på Facebook Juli 2021 Om rapporten Den 31. december 2019 advarer Kina for første gang om udbrud af noget, I denne rapport dykker vi ned i debatten om corona i danske mediers og som man mener, er en form for lungebetændelse i Wuhanprovinsen. En politikers kommentarspor på Facebook fra starten af 2020 til og med måned senere, den 30. januar 2020, erklærer WHO udbruddet af februar 2021. Hvad var omfanget af debatten? Hvad diskuterede vi mest? coronavirus for en ”International nødssituation”. Samme dag offentliggør Hvad hidsede vi os op over? Og inden for hvilke emner udviste vi mest den danske Sundhedsstyrelse en udmelding om, at ”faren for, at en anerkendelse? smittet person kommer til Danmark er lav”. Mens coronaen har raset udenfor vinduet det seneste år, har vi trænet to I dag raser coronapandemien på andet år, og Danmark har – sammen med sprogalgoritmer til at detektere hhv. sproglige angreb og sproglig resten af verden – gennemlevet den største sundhedskrise i nyere tid. anerkendelse i kommentarsporene. Med brug af big data analyse og de to Siden 2020 har ord som restriktioner, samfundssind, forsamlingsforbud, algoritmer kan vi nu for første gang analysere tonen og temaerne i den tillid, vaccine, smittetryk, mink og nedlukning været på lystavlen hos de samlede offentlige debat om corona, som den tog sig ud på 199 politikeres fleste danskere. Pandemien - og ikke mindst håndteringen af den - har og 477 mediers Facebooksider siden starten af 2020. været debatteret heftigt over kaffen, over hækken, på tv og ikke mindst på God læselyst! Facebook. -

Pdf Dokument

Udskriftsdato: 24. september 2021 2016/1 BTB 130 (Gældende) Betænkning over Forslag til folketingsbeslutning om behandlingsret inden for behandling af type 1diabetes Ministerium: Folketinget Betænkning afgivet af Sundheds- og Ældreudvalget den 30. maj 2017 Betænkning over Forslag til folketingsbeslutning om behandlingsret inden for behandling af type 1-diabetes [af Kirsten Normann Andersen (SF) og Jacob Mark (SF)] 1. Udvalgsarbejdet Beslutningsforslaget blev fremsat den 31. marts 2017 og var til 1. behandling den 17. maj 2017. Beslut- ningsforslaget blev efter 1. behandling henvist til behandling i Sundheds- og Ældreudvalget. Møder Udvalget har behandlet beslutningsforslaget i 2 møder. 2. Indstillinger og politiske bemærkninger Et flertal i udvalget (S, DF, V, LA, RV og KF) indstiller beslutningsforslaget til forkastelse. Dansk Folkepartis medlemmer af udvalget er enige med forslagsstillerne i, at det er uacceptabelt, at det er så vanskeligt for de mennesker, som får stillet en diabetesdiagnose og med lægens ord kan have gavn af en insulinpumpe og en glukosesensor at få dette. Det er samtidig urimeligt, at der skal være så store forskelle, alt efter hvilken region man bor i. Men da der p.t. verserer en sag i Ankestyrelsen, ønsker DF at afvente Ankestyrelsens afgørelse og tage disse udfordringer med i den diabetesplan, som skal udarbejdes sammen med satspuljepartierne. Et mindretal i udvalget (EL, ALT og SF) indstiller beslutningsforslaget til vedtagelse uændret. Socialistisk Folkepartis medlemmer af udvalget stemmer for beslutningsforslaget, fordi der er borgere og familier, der her og nu er i klemme, fordi regioner og kommuner stadig ikke kan blive enige om, hvem der skal bevilge de nødvendige glukosesensorer og insulinpumper. -

Betænkning Afgivet Af Uddannelses- Og Forskningsudvalget Den 27

Til lovforslag nr. L 210 Folketinget 2020-21 Betænkning afgivet af Uddannelses- og Forskningsudvalget den 27. maj 2021 Betænkning over Forslag til lov om ændring af lov om akkreditering af videregående uddannelsesinstitutioner (Uddannelsesfilialer) [af uddannelses- og forskningsministeren (Ane Halsboe-Jørgensen)] 1. Ændringsforslag [Afgrænsning af henlæggelse af uddannelser og uddannel‐ Enhedslistens medlemmer af udvalget har stillet 1 æn‐ sesudbud til uddannelsesfilialer] dringsforslag til lovforslaget. 4. Udvalgsarbejdet 2. Indstillinger Lovforslaget blev fremsat den 14. april 2021 og var til Et flertal i udvalget (udvalget med undtagelse af EL og 1. behandling den 28. april 2021. Lovforslaget blev efter 1. LA) indstiller lovforslaget til vedtagelse uændret. behandling henvist til behandling i Uddannelses- og Forsk‐ Et mindretal i udvalget (EL) indstiller lovforslaget til ningsudvalget. vedtagelse med det stillede ændringsforslag. Et andet mindretal i udvalget (LA) indstiller lovforslaget Oversigt over lovforslagets sagsforløb og dokumenter til forkastelse ved 3. behandling. Mindretallet vil stemme Lovforslaget og dokumenterne i forbindelse med ud‐ imod det stillede ændringsforslag. valgsbehandlingen kan læses under lovforslaget på Folketin‐ Alternativet, Kristendemokraterne, Inuit Ataqatigiit, Si‐ gets hjemmeside www.ft.dk. umut, Sambandsflokkurin og Javnaðarflokkurin havde ved betænkningsafgivelsen ikke medlemmer i udvalget og der‐ Møder med ikke adgang til at komme med indstillinger eller politi‐ Udvalget har behandlet lovforslaget i 2 møder. ske bemærkninger i betænkningen. Høringssvar En oversigt over Folketingets sammensætning er optrykt Et udkast til lovforslaget har inden fremsættelsen været i betænkningen. sendt i høring, og uddannelses- og forskningsministeren 3. Ændringsforslag med bemærkninger sendte den 11. februar 2021 dette udkast til udvalget, jf. UFU alm. del – bilag 51. Den 14. april 2021 sendte ud‐ Ændringsforslag dannelses- og forskningsministeren høringssvarene og et hø‐ ringsnotat til udvalget. -

Ugeplan for Folketinget

Ugeplan for Folketinget Udkast Ugeplan for Folketinget 16. marts - 22. marts 2020 (Uge 12) Tirsdag den 17. marts 2020 kl. 13.00 11. marts 2020 Lovsekretariatet 1. behandling af forslag til lov om ændring af lov om fremme af besparelser i (L 116) KEF energiforbruget, lov om fremme af energibesparelser i bygninger, afskrivningsloven og ligningsloven samt ophævelse af en række love under Klima-, Energi- og Forsyningsministeriets område. (Tilskud til energibesparelser og energieffektiviseringer m.v.). (Af klima-, energi- og forsyningsministeren) 1. behandling af forslag til lov om ændring af lov om luftfart og ophævelse af (L 120) TRU lov om forlængelse af Danmarks deltagelse i det skandinaviske luftfartssamarbejde. (Offentliggørelse af nationalitetsregistret, arbejdsmiljø samt indberetning af begivenheder). (Af transportministeren) 1. behandling af forslag til lov om ændring af lov om luftfart. (Harmonisering (L 121) TRU af droneområdet). (Af transportministeren) Onsdag den 18. marts 2020 kl. 13.00 Forespørgsel til statsministeren af Kristian Thulesen Dahl (DF), Mads (F 55) UUI Fuglede (V), Pernille Vermund (NB) og Alex Vanopslagh (LA) om at flygtninge- og migrantstrømmen fra Tyrkiet stoppes, inden den når ind over Danmarks grænser. (Hasteforespørgsel). Eventuel afstemning udsættes til tirsdag den 24. april 2020. Spørgetiden starter kl. 15.00. Besvarelse af oversendte spørgsmål til ministrene (spørgetid). 1. behandling af forslag til folketingsbeslutning om at ophæve (B 59) TRU arealreservationer i den nordlige Ring 5-transportkorridor. (Af Martin Lidegaard (RV), Morten Messerschmidt (DF), Anne Valentina Berthelsen (SF), Henning Hyllested (EL), Mette Abildgaard (KF), Susanne Zimmer (ALT) og Mette Thiesen (NB) m.fl.) 1. behandling af forslag til lov om ændring af lov om kystbeskyttelse, lov om (L 132) MOF miljøvurdering af planer og programmer og af konkrete projekter (VVM) og lov om planlægning. -

Foghs Enegang Bringer Dansk EU-Enhed I Fare

Nr.4_side_35-39.qxd 24-01-03 18:09 Side 35 Mandagmorgen EU Foghs enegang bringer dansk EU-enhed i fare Sololøb. Fogh orienterede medierne om sine EU-visioner før ja-partierne - Det bryder med mange års koor- dinering af EU-politikken og kan svække dansk indflydelse i EU - Flere udmeldinger er vidtgående og har ikke garanti for flertal i Folketinget - Debatten om en EU-præsident har overskygget de øvrige udspil BRUXELLES - Da statsministeren onsdag i forrige uge re- og socialminister mener ikke, at Socialdemokratiet skulle præsentere sine EU-visioner ved en tale i Dansk og de Radikale skal aftale alting i detaljer med regerin- Institut for Internationale Studier (DIIS), var medierne gen, men peger på, at en tæt kontakt er naturlig, og at bedre orienteret om talens indhold end både de leden- det også hidtil har været sådan. de ja-partier og Udenrigsministeriet. Statsministerens Hverken Niels Helveg Petersen eller Henrik Dam tale var dagen forinden blevet lækket til danske og Kristensen, der er de to ja-partiers repræsentanter i udenlandske medier - bl.a. Politiken og Financial Konventet om Europas fremtid, var orienteret om Times. På samme tidspunkt blev Udenrigsministeriet statsministerens stribe af ganske detaljerede forslag bekendt med talens indhold, mens de ledende politi- eller begrundelsen for dem. De to, der i høj grad er kere fra Socialdemokratiet og de Radikale, der skal med til at tegne oppositionens EU-holdninger, hørte bære fremtidens danske europapolitik igennem sam- først om Foghs EU-forslag, da pressen udbad sig men med V og K, ikke var orienterede om tankerne i kommentarer. De kendte f.eks.