Art Spiegelman, Metamaus. a Look Inside a Modern Classic (New York: Pantheon Books, 2011), Pp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Graphic Novels for Children and Teens

J/YA Graphic Novel Titles The 9/11 Report: A Graphic Adaptation Sid Jacobson Hill & Wang Gr. 9+ Age of Bronze, Volume 1: A Thousand Ships Eric Shanower Image Comics Gr. 9+ The Amazing “True” Story of a Teenage Single Mom Katherine Arnoldi Hyperion Gr. 9+ American Born Chinese Gene Yang First Second Gr. 7+ American Splendor Harvey Pekar Vertigo Gr. 10+ Amy Unbounded: Belondweg Blossoming Rachel Hartman Pug House Press Gr. 3+ The Arrival Shaun Tan A.A. Levine Gr. 6+ Astonishing X-Men Joss Whedon Marvel Gr. 9+ Astro City: Life in the Big City Kurt Busiek DC Comics Gr. 10+ Babymouse Holm, Jennifer Random House Children’s Gr. 1-5 Baby-Sitter’s Club Graphix (nos. 1-4) Ann M. Martin & Raina Telgemeier Scholastic Gr. 3-7 Barefoot Gen, Volume 1: A Cartoon Story of Hiroshima Keiji Nakazawa Last Gasp Gr. 9+ Beowulf (graphic adaptation of epic poem) Gareth Hinds Candlewick Press Gr. 7+ Berlin: City of Stones Berlin: City of Smoke Jason Lutes Drawn & Quarterly Gr. 9+ Blankets Craig Thompson Top Shelf Gr. 10+ Bluesman (vols. 1, 2, & 3) Rob Vollmar NBM Publishing Gr. 10+ Bone Jeff Smith Cartoon Books Gr. 3+ Breaking Up: a Fashion High graphic novel Aimee Friedman Graphix Gr. 5+ Buffy the Vampire Slayer (Season 8) Joss Whedon Dark Horse Gr. 7+ Castle Waiting Linda Medley Fantagraphics Gr. 5+ Chiggers Hope Larson Aladdin Mix Gr. 5-9 Cirque du Freak: the Manga Darren Shan Yen Press Gr. 7+ City of Light, City of Dark: A Comic Book Novel Avi Orchard Books Gr. -

Check All That Apply)

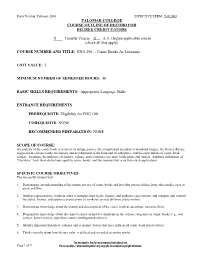

Form Version: February 2001 EFFECTIVE TERM: Fall 2003 PALOMAR COLLEGE COURSE OUTLINE OF RECORD FOR DEGREE CREDIT COURSE X Transfer Course X A.A. Degree applicable course (check all that apply) COURSE NUMBER AND TITLE: ENG 290 -- Comic Books As Literature UNIT VALUE: 3 MINIMUM NUMBER OF SEMESTER HOURS: 48 BASIC SKILLS REQUIREMENTS: Appropriate Language Skills ENTRANCE REQUIREMENTS PREREQUISITE: Eligibility for ENG 100 COREQUISITE: NONE RECOMMENDED PREPARATION: NONE SCOPE OF COURSE: An analysis of the comic book in terms of its unique poetics (the complicated interplay of word and image); the themes that are suggested in various works; the history and development of the form and its subgenres; and the expectations of comic book readers. Examines the influence of history, culture, and economics on comic book artists and writers. Explores definitions of “literature,” how these definitions apply to comic books, and the tensions that arise from such applications. SPECIFIC COURSE OBJECTIVES: The successful student will: 1. Demonstrate an understanding of the unique poetics of comic books and how that poetics differs from other media, such as prose and film. 2. Analyze representative works in order to interpret their styles, themes, and audience expectations, and compare and contrast the styles, themes, and audience expectations of works by several different artists/writers. 3. Demonstrate knowledge about the history and development of the comic book as an artistic, narrative form. 4. Demonstrate knowledge about the characteristics of and developments in the various subgenres of comic books (e.g., war comics, horror comics, superhero comics, underground comics). 5. Identify important historical, cultural, and economic factors that have influenced comic book artists/writers. -

A Video Conversation with Pulitzer Prize Recipient Art Spiegelman

Inspicio the last laugh Introduction to Art Spiegelman. 1:53 min. Photo & montage by Raymond El- man. Music: My Grey Heaven, from Normalology (1996), by Phillip Johnston, Jedible Music (BMI) A Video Conversation with Pulitzer Prize Recipient Art Spiegelman By Elman + Skye From the Steven Barclay Agency: rt Spiegelman (b. 1948) has almost single-handedly brought comic books out of the toy closet and onto the A literature shelves. In 1992, he won the Pulitzer Prize for his masterful Holocaust narrative Maus— which por- trayed Jews as mice and Nazis as cats. Maus II continued the remarkable story of his parents’ survival of the Nazi regime and their lives later in America. His comics are best known for their shifting graphic styles, their formal complexity, and controver- sial content. He believes that in our post-literate culture the im- portance of the comic is on the rise, for “comics echo the way the brain works. People think in iconographic images, not in holograms, and people think in bursts of language, not in para- graphs.” Having rejected his parents’ aspirations for him to become a dentist, Art Spiegelman studied cartooning in high school and began drawing professionally at age 16. He went on to study art and philosophy at Harpur College before becoming part of the underground comix subculture of the 60s and 70s. As creative consultant for Topps Bubble Gum Co. from 1965-1987, Spie- gelman created Wacky Packages, Garbage Pail Kids and other novelty items, and taught history and aesthetics of comics at the School for Visual Arts in New York from 1979-1986. -

Art Spiegelman in Conversation and with Phillip Johnston: Martin Scorsese WORDLESS!

2014 Winter/Spring Season JAN 2014 Bill Beckley, I’m Prancin, 2013, Cibachrome photograph, 72”x48” Published by: BAM 2014 Winter/Spring Sponsor: BAM 2014 Winter/Spring Season #FRANLEBOWITZ #WORDLESS Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Karen Brooks Hopkins, Chairman of the Board President William I. Campbell, Joseph V. Melillo, Vice Chairman of the Board Executive Producer Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board Fran Lebowitz Art Spiegelman in Conversation and with Phillip Johnston: Martin Scorsese WORDLESS! BAM Howard Gilman Opera House Words / Music / Comix Jan 19 at 7pm BAM Howard Gilman Opera House Approximate running time: one hour and 30 minutes; no intermission Jan 18 at 7:30pm Approximate running time: one hour and 30 minutes; no intermission Picture stories by Frans Masereel, H.M. Bateman, Lynd Ward, Otto Nuckel, Milt Gross, Si Lewen, and Art Spiegelman Music by Phillip Johnston Originally commissioned by Sydney Opera House for GRAPHIC BAM 2014 Winter/Spring Season sponsor: Fran LebowitzinConversationwithMartin Scorsese Fran Public Speaking Public Fran Lebowitz. Photo courtesy Fran Who’s Who FRAN LEBOWITZ portant that you emphasize similarities... there is practically nobody willing to identify themselves as American anymore because everybody is too Purveyor of urban cool, witty chronicler of the busy identifying themselves with the area of their ”me decade,” and the cultural satirist whom lives in which they feel the most victimized.” On many call the heir to Dorothy Parker, Fran aging: “At a certain point, the worst picture taken Lebowitz remains one of the foremost advocates of you when you are 25 is better than the best of the Extreme Statement. -

Západočeská Univerzita V Plzni Fakulta Filozofická Bakalářská Práce

Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Bakalářská práce Art Spiegelman – “Of Mice and Men” Monika Majtaníková Plzeň 2014 Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Katedra anglického jazyka a literatury Studijní program Filologie Studijní obor Cizí jazyky pro komerční praxi Kombinace angličtina – němčina Bakalářská práce Art Spiegelman – “Of Mice and Men” Monika Majtaníková Vedoucí práce: Mgr. et Mgr. Jana Kašparová Katedra anglického jazyka a literatury Fakulta filozofická Západočeské univerzity v Plzni Plzeň 2014 Prohlašuji, že jsem práci zpracoval(a) samostatně a použil(a) jen uvedených pramenů a literatury. Plzeň, duben 2014 ………………………….......... Acknowledgement I would like to express my honest acknowledgement to my supervisor, Mgr. et Mgr. Jana Kašparová, for her professional guidance, useful advice, patience and continual support. Table of Contents 1 Introduction .................................................................................................... 1 2 Art Spiegelman ............................................................................................... 2 2.1 Early life .................................................................................................. 2 2.2 Education ................................................................................................. 3 2.3 Beginning of his writing career ............................................................... 4 2.4 Personal and contemporary life ............................................................... 9 2.5 Interesting -

Maybe More Than the Reading, I Enjoyed the Pictures. I Was Raised in a Strictly Spanish-Speaking Household, Where English Was Only My Second Language at School

Preface: A Powerful Language I’ve always enjoyed reading; maybe more than the reading, I enjoyed the pictures. I was raised in a strictly Spanish-speaking household, where English was only my second language at school. So reading (especially out loud) was always a bit more challenging for me growing up. Nevertheless, I always tried but I never got the same satisfaction of understanding when I read a regular book, as opposed to when I’d read a book with pictures. Far from being interested in children’s books, I was reading Jim Davis’ collections of Garfield comic strips in my childhood. Though, many of the adults around me didn’t consider this to be adequate reading for me.1 They didn’t see how I could ever benefit from reading three- panel illustrations. Well actually, these witty comic strips were the gateway into reading for me.2 Sometime around the beginning of high school, I got my hands on a copy of Alan Moore’s Watchmen. It was the first time I experienced a graphic novel and I loved it. I loved it so much I became obsessed with that book and read it multiple times and shared it with others. And that’s how I became hooked on graphic novels. Introduction: Guess How I Started I spent over two weeks reading graphic novels and comics…for fun. It was really relaxing, even though I had to go through all of my reads at a pretty fast pace because I had so many books. The ratio of books I read in that amount of time was astonishing. -

The Memory and Legacy of Trauma in Art Spiegelman's Maus Author(S): Puneet Kohli Source: Prandium - the Journal of Historical Studies, Vol

The Memory and Legacy of Trauma in Art Spiegelman's Maus Author(s): Puneet Kohli Source: Prandium - The Journal of Historical Studies, Vol. 1, No. 1 (Spring, 2012). Published by: The Department of Historical Studies, University of Toronto Mississauga Stable URL: http://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/prandium/editor/submission/16285/ Prandium: The Journal of Historical Studies 1 The Memory and Legacy of Trauma in Art Spiegelman’s Maus “Historical understanding is like a vision, or rather like an evocation of images”1 Amongst the plethora of Holocaust literature, monuments, films, documentaries, and exhibitions, Art Spiegelman’s graphical representation of the Holocaust and its memory in Maus I and II is one of the most poignant, striking, and creative. Groundbreaking in his approach, Spiegelman reinterprets and expands both the comic form and traditional mediums of telling history to express and relate the history of his survivor-father. Spiegelman also explores and addresses the burden and legacy of traumatic memory on second-generation survivors. Interweaving a variety of genres, characterizations, temporalities, and themes, Maus depicts the process of, and Spiegelman’s relationship to, remembrance through a combination of images and text. This paper situates Spiegelman’s work within the framework of second-generation Holocaust literature and post-memory, and will discuss the debate regarding Spiegelman’s representation of the memory process and the Holocaust in the comic medium, along with his use of animal characters instead of humans. Moreover the essay will critically analyze and enumerate the various themes within Maus such as the relation between past and present and the recording of memory. -

Graphic Novels in Academic Libraries: from Maus to Manga and Beyond

This article is a post-print copy. The final published article can be accessed at: O’English, L. Matthews, G., & Blakesley, E. (2006). Graphic novels in academic libraries: From Maus to manga and beyond. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 32(2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2005.12.002. Graphic Novels in Academic Libraries: From Maus to Manga and Beyond Lorena O’English Social Sciences Reference/Instruction Librarian Washington State University Libraries PO Box 645610 Pullman WA 99164-5610 [email protected] J. Gregory Matthews Cataloging Librarian Washington State University Libraries PO Box 645610 Pullman WA 99164-5610 [email protected] Elizabeth Blakesley Lindsay Assistant Dean, Public Services and Outreach Former Head, Library Instruction Washington State University Libraries PO Box 645610 Pullman WA 99164-5610 [email protected] 1 Graphic Novels in Academic Libraries: From Maus to Manga and Beyond Abstract This article addresses graphic novels and their growing popularity in academic libraries. Graphic novels are increasingly used as instructional resources, and they play an important role in supporting the recreational reading mission of academic libraries. The article will also tackle issues related to the cataloging and classification of graphic novels and discuss ways to use them for marketing and promotion of library services. A Brief Introduction to Graphic Novels Graphic novels grew out of the comic book movement in the 1960s and came into existence at the hands of writers who were looking to use the comic book format to address -

Superhero Comics: Artifacts of the U.S. Experience Dr

Superhero Comics: Artifacts of the U.S. Experience Dr. Julian C. Chambliss Sequential SmArt: A Conference on Teaching with Comics, May 19, 2012 Julian Chambliss is Associate Professor of History at Rollins College. n the last two decades, comic books and comic book heroes have experienced increased scholarly I interest. This attention has approached comic books and characters as myth, sought context of the superhero archetype, and used comic books as cultural markers for postwar America. What all of these efforts share is an acknowledgement that comic books and superheroes offer a distinct means to understand U. S. culture.1 The place of comic books in contemporary discussion of the American experience has been seen as space linked to popular culture. The comic book genre, especially its most popular aspect, the superhero, uses visual cues to reduce individual characters into representations of cultural ideas. This process has allowed characters to become powerful representations of nationalism (Superman), or the search for societal stability (Batman), or struggles over femininity (Wonder Woman). Scholars have established the importance of heroic characterization as a means to inform societal members about collective expectations and behavioral ideas.2 In many ways, the use of comics in the classroom has become standardized over the last few years as teachers have discovered the medium’s ability to engage students. Indeed, academic conferences like this one have grown in number as scholars have rediscovered what we all know: kids who read comics tend to go on and read other material.3 Perhaps the most visible and lauded use of comics is in the History classroom, following the pattern established with the successful integration of comics focused on war and politics, found notably in Maus by Art Spiegelman and, more recently, in Alan’s War: The Memories of G.I. -

The Politics of Truth and Reconciliation in Post-Conflict Comics

Redwood, H. and Wedderburn, A. (2019) A cat-and-Maus game: the politics of truth and reconciliation in post-conflict comics. Review of International Studies, 45(4), pp. 588-606. (doi: 10.1017/s0260210519000147). This is the author’s final accepted version. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/210169/ Deposited on: 19 February 2020 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk A CAT-AND-MAUS GAME: THE POLITICS OF TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION IN POST-CONFLICT COMICS Henry Redwood, King’s College London A: The Strand, London, WC2R 2LS, UK. E: [email protected] BIO: Henry Redwood is an ESRC post-doctoral fellow in the Department of War Studies, King's College London. Alister Wedderburn, Australian National University. A: 130 Garran Road, Canberra, ACT, Australia. E: [email protected] BIO: Alister Wedderburn is the John Vincent Postdoctoral Research Fellow in International Relations at the Australian National University. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: Previous iterations of this paper were read by Tim Aistrope, Claudia Aradau, Lindsay Clark, Kyle Grayson, Luke Hennessy, Rachel Kerr, Rhiannon Nielsen, Dave Norman and Ben Zala. We are grateful to all of them for their engagement. Thanks are also owed to the RIS editorial team and the three reviewers for their constructive and generous stewardship. Sierrarat is reproduced here with the permission of John Caulker. MAUS: A Survivor’s Tale: My Father Bleeds History, Copyright © Art Spiegelman, 1973, 1980, 1981, 1982, 1983, 1984, 1985, 1986. -

Stony Brook University

SSStttooonnnyyy BBBrrrooooookkk UUUnnniiivvveeerrrsssiiitttyyy The official electronic file of this thesis or dissertation is maintained by the University Libraries on behalf of The Graduate School at Stony Brook University. ©©© AAAllllll RRRiiiggghhhtttsss RRReeessseeerrrvvveeeddd bbbyyy AAAuuuttthhhooorrr... The Graphic Memoir and the Cartoonist’s Memory A Dissertation Presented by Alice Claire Burrows to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature Stony Brook University August 2016 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Alice Claire Burrows We, the dissertation committee for the above candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this dissertation. _________________________________________________________ Raiford Guins, Professor, Chairperson of Defense _________________________________________________________ Robert Harvey, Distinguished Professor, Cultural Analysis & Theory, Dissertation Advisor _________________________________________________________ Krin Gabbard, Professor Emeritus, Cultural Analysis & Theory _________________________________________________________ Sandy Petrey, Professor Emeritus, Cultural Analysis & Theory _________________________________________________________ David Hajdu, Associate Professor, Columbia University, Graduate School of Journalism This dissertation is accepted by the Graduate School ___________________________ Charles Taber Dean of the Graduate School ii Abstract of the Dissertation -

The Depiction of Jewish People's Struggle Against Negative

THE DEPICTION OF JE:,SH 3E23/E‘S STR8GG/E AGAINST NEGATIVE STEREOTYPES IN ART SP,EGE/MA1‘S GRA3H,C 129E/ MAUS Nasti Mudita Study Program of English, Faculty of Cultural Studies, Universitas Brawijaya ABSTRACT Jewish people have been facing discrimination and negative stereotyping for ages. Conflicts between the majority and Jewish communities, propagated by racial prejudice, result in violent acts committed by the society to isolate the Jews. MAUS is a biography of Art Spiegelman‘s father, 9ladeN Spiegelman, which tells about his experience in surviving the persecution of Jewish people in Poland during :orld :ar ,,, and also about Art Spiegelman‘s efforts to defy the lingering stereotypes of Jewish people in the present. This research is conducted to analyze the acts of discrimination and negative stereotyping against -ews and the author‘s efforts to defy them. Sociological approach is utilized in this research in order to explain the root of prejudice and discrimination against Jewish people, as well as the negative stereotypes labeled to them. The finding of this research shows that Vladek Spiegelman, the main character, faced various violent discriminatory acts inflicted against Jews due to the 1azi‘s racial propaganda. The propaganda affected the majority by creating an ingroup-outgroup bias, thus forcing the minority Jews into isolation. Nevertheless, Vladek Spiegelman survived using cunningness and hard-work ethic; both are stereotypes highly associated with Jews. On the other hand, Art Spiegelman faced difficulties in portraying his father in the graphic novel, since Vladek Spiegelman‘s aforementioned positive traits becomes negative in the present. The father-and-son conflict brought Art Spiegelman into self-doubting his identity as a Jew.