Gilded Age and Bureaucratic Accounts of the Minisink, 1889 to the Present Wendy Harris

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE INDIANS of LENAPEHOKING (The Lenape Or Delaware Indians)

THE INDIANS OF LENAPEHOKING (The Lenape or Delaware Indians) By HERBERT C.KRAFT NCE JOHN T. KRAFT < fi Seventeenth Century Indian Bands in Lenapehoking tN SCALE: 0 2 5 W A P P I N Q E R • ' miles CONNECTICUT •"A. MINISS ININK fy -N " \ PROTO-MUNP R O T 0 - M U S E*fevj| ANDS; Kraft, Herbert rrcrcr The Tndians nf PENNSYLVANIA KRA hoking OKEHOCKING >l ^J? / / DELAWARE DEMCO NO . 32 •234 \ RINGVyOOP PUBLIC LIBRARY, NJ N7 3 6047 09045385 2 THE INDIANS OF LENAPEHOKING by HERBERT C. KRAFT and JOHN T. KRAFT ILLUSTRATIONS BY JOHN T. KRAFT 1985 Seton Hall University Museum South Orange, New Jersey 07079 145 SKYLAND3 ROAD RINGWOOD, NEW JERSEY 07456 THE INDIANS OF LENAPEHOKING: Copyright(c)1985 by Herbert C. Kraft and John T. Kraft, Archaeological Research Center, Seton Hall University Museum, South Orange, Mew Jersey. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book--neither text, maps, nor illustrations--may be reproduced in any way, including but not limited to photocopy, photograph, or other record without the prior agreement and written permission of the authors and publishers, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address Dr. Herbert C. Kraft, Archaeological Research Center, Seton Hall University Museum, South Orange, Mew Jersey, 07079 Library of Congress Catalog Number: 85-072237 ISBN: 0-935137-00-9 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The research, text, illustrations, and printing of this book were made possible by a generous Humanities Grant received from the New Jersey Department of Higher Education in 1984. -

![Land Title Records in the New York State Archives New York State Archives Information Leaflet #11 [DRAFT] ______](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8699/land-title-records-in-the-new-york-state-archives-new-york-state-archives-information-leaflet-11-draft-1178699.webp)

Land Title Records in the New York State Archives New York State Archives Information Leaflet #11 [DRAFT] ______

Land Title Records in the New York State Archives New York State Archives Information Leaflet #11 [DRAFT] __________________________________________________________________________________________________ Introduction NEW YORK STATE ARCHIVES Cultural Education Center Room 11A42 The New York State Archives holds numerous records Albany, NY 12230 documenting title to real property in New York. The records range in date from the early seventeenth century to Phone 518-474-8955 the near present. Practically all of the records dating after FAX 518-408-1940 the early nineteenth century concern real property E-mail [email protected] acquired or disposed by the state. However, many of the Website www.archives.nysed.gov earlier records document conveyances of real property ______________________________________________ between private persons. The Archives holds records of grants by the colony and state for lands above and under Contents: water; deeds issued by various state officers; some private deeds and mortgages; deeds to the state for public A. Indian Deeds and Treaties [p. 2] buildings and facilities; deeds and cessions to the United B. Dutch Land Grants and Deeds [p. 2] States; land appropriations for canals and other public purposes; and permits, easements, etc., to and from the C. New York Patents for Uplands state. The Archives also holds numerous records relating and Lands Under Water [p. 3] to the survey and sale of lands of the colony and state. D. Applications for Patents for Uplands and Lands Under Water [p. 6] This publication contains brief descriptions of land title records and related records in the Archives. Each record E. Deeds by Commissioners of Forfeitures [p. 9] series is identified by series number (five-character F. -

Our Town and Schools (Pdf)

OUR TOWN HISTORY As the melting Wisconsin Glacier slowly retreated north 20,000 years ago, it left behind Lake Passaic in the curves of the Watchung Mountains. The land that is now Chatham was at the bottom of that lake, nearly 160 feet below the surface. The only visible sign of what would become Chatham was a long island formed by the top of the hill at Fairmount Avenue, known as Long Hill. Lake Passaic drained into the sea when the ice cap melted near Little Falls. The Passaic River slowly made its winding path through the marshlands. Early Settlers Six or seven thousand years ago the first people to settle in the area were the Lenni Lenape (“Original People”) Indians. It is believed that the Lenape migrated from Canada and possibly Siberia in search of a warmer climate. The Minsi group of Lenni Lenape occupied the northern section of New Jersey, including the area of present-day Chatham. In early summer the Lenape journeyed to the sea to feast on clams and oysters. Traveling from the northwest, they followed a path along the Passaic River through the Short Hills to the New Jersey shore. The trail became known as the Minisink Trail and followed a route that includes what is now Main Street in Chatham. The Lenni Lenape forded the Passaic River at a shallow point east of Chatham at a place they called “the Crossing of the Fishawack in the Valley of the Great Watchung.” “Fishawack” and “Passaic” are two versions of the many ways early settlers tried to spell the name they heard the Indians call the river. -

Pike Heritage for Website-2

209 East Harford Street Milford, PA 18337 570-296-8700 www.pikechamber.com Four Guided Tours by Automobile Highlighting the Historic Sites and Natural Heritage of Pike County, Pennsylvania • Bushkill to Historic Milford to Matamoras • Shohola to Lackawaxen to Kimbles • • Lake Wallenpaupack • Greentown to Promised Land to Pecks Pond • • Historic Sites and Places • Natural and Recreational Areas • Welcome to Pike County! For the convenience of you, the heritage-interested traveler, the diamond-shaped geography of Pike County has been divided into four tours, each successively contiguous to the next, making a complete circuit. With this design in mind, you are now ready to begin your exploration of Pike County. Enjoy! D e l a w a re R i v e LACKAWAXEN r K rTw Minisink Ford, NY ou o New York T Rowland I Barryville, NY Kimbles 4006 d J H R L s e bl Wilsonville im Lackawaxen Lackawaxen G Shohola K M River T o N u r Tw Paupack Tafton Greeley SHOHOLA o Mill Rift O Blooming 1 New York e Grove 0 e 0 13 Twin 7 0 r 1 h Lakes T T PALMYRA Lords Valley 101 Port Jervis, NY Shohola MILFORDWESTFALL 7 84 o ur Falls 84 Pike County r Park F u Matamoras Greentown BLOOMING o GREENE F GROVE DINGMAN 84 209 P r E 6 u Gold Key C e r o Pecks Cliff Park D R i v T PROMISED LAND Lake 1 re Pond 00 Milford Q STATE PARK T 20 2 a 09 B o w Raymondskill a u Falls l r e F e D o A n R u N 200 O r 4 G r W u D New Jersey o T PORTER Childs Pennsylvania Recreation Site DELAWARE Dingmans Ferry Bridge Dingmans Falls 2 Dingmans Ferry 0 0 3 PEEC A Delaware Water Gap LEHMAN National Recreation Area A R Mountain Laurel N e Center for the G W n Performing Arts1 0 D 0 O Bushkill 2 ur Falls To Bushkill Tour Starts Here Map by James Levell 209 East Harford Street Milford, PA 18337 570-296-8700 www.pikechamber.com tarting at the light on US Route 209 in Bushkill, you are in the middle of the Dela- ware Water Gap National Recreation Area (DWGNRA) on the Pennsylvania side of the Delaware River. -

Elmira C. Jerome, Chippewa. Minacinink, the Indian Word For

A WEEKLY NEWSPAPER EDITED AND PRINTED BY THE STUDENTS OF THE CARLISLE INDIAN INDUSTRIAL SCHOOL VOLUME FIVE CARLISLE, PA., NOVEMBER 6, 1908 NUMBER NINE THE MUNSEE INDIANS. and other tribes, so that the Munsee should not feel above those lower, or were all scattered. Therefore it is be jealous of those who are trying to Elmira C. Jerome, Chippewa. almost impossible to estimate their reach the top. No matter how sim Minacinink, the Indian word for exact numbers. In 1765 those on the ple the task is do it willingly and Munsee, means a place where Susquehanna numbered about 750. do not do the easiest work and leave stones are gathered together. The In 1843 those living in the United the harder for some one else. Munsee, being one of the three States, mostly with the Delaware A person who works with a cheer principal divisions of the Delaware in Kansas, were about 200 in number, ful face and spirit can accomplish tribe of Indians, have also the three while the others, besides those who much more than the one who goes most important clans, as the Dela had moved to Canada, were with the about his work grumbling. ware, namely, Wolf, Turtle and Tur Shawnee and Stockbridge. ^ /// key. The Munsee are known as the In 1885 the only Munsee Indians MY VISIT TO THE SHOE SHOP. Wolf tribe of the Delaware. They recognized in the United States were formerly occupied the regions around living with a band of Chippewas in Edith Harris, Catawba. the headwaters of the Delaware in Franklin county, Kansas, and to New York, New Jersey and Pennsyl gether numbered only 72. -

Introduction: the Dutch-Munsee Frontier

– Introduction – THE DUTCH-MUNSEE FRONTIER “We regard the frontier not as a boundary or line, but as a territory or zone of interpenetration between two previously distinct societies.” Howard Lamar and Leonard Thompson, The Frontier in History1 n New Netherland, the Dutch colony that would later become New IYork, Europeans and Native Americans coexisted, interacting with one another throughout the life of the colony. Europeans and the indigenous inhabitants of the Hudson River valley first encountered one another in 1524 during the voyage of Giovanni da Verrazzano. Sustained contact between the two groups began in 1609 when Henry Hudson rediscov- ered the region for Europeans. He was quickly followed by Dutch mer- chants and traders, transient settlers, and finally permanent European colonists. Over time, the Dutch extended their political sovereignty over land already claimed by Native Americans. In this territory, Indians and Europeans interacted on a number of levels. They exchanged land and goods, lived as neighbors, and faced one another in European courts. During their interaction, periods of peace and relative harmony were punctuated by outbreaks of violence and warfare. After seventy years, Europeans and Indians continued to coexist in the lower Hudson River valley. Some Native people had been vanquished from their traditional homelands such as Manhattan Island. Others remained, many living in close proximity to the Dutch and other Europeans. While many native people maintained their own cultural outlook, others clearly became acculturated to one degree or another. All lived in a society which was dominated politically and economically by Europeans, forcing Native Americans to at least accommodate themselves to the Dutch, and at times to modify their cultural practices in order to survive in an increas- ingly European-dominated context. -

Lenape Ridge to Minisink Trail Loop at Huckleberry Ridge State Forest

JOE 2019 Information Packet for Moderate Lenape Ridge/Minisink Trail Loop Hike (afternoon) Day: Saturday Afternoon Start Time: 12:30 pm End Time: 4:30 pm Co-Leader: Terry Auspitz Co-Leader: Gayle Nadler Limit: 12 people Transportation: Personal Cars Driver: Terry Auspitz - Car Radios: 2 / First Aid Kit: 1 Susan Kappel - Car Catherine Gibson - Car Fees: none Travel Distance: 14 Mile – One way Travel Time: 16 Min.- One Way Moderate Lenape Ridge/Minisink Trail Loop Hike (afternoon) This easy-moderate loop hike follows the Lenape Ridge within the Huckleberry Ridge State Forest, with interesting vegetation and panoramic views over the Heinlein Pond, Shawangunk Ridge in NY, High Point in NJ and beyond. This hike is a very simple, narrow loop, a four-mile hike which passes through rhododendron and hemlock forests. Since it is a ridge walk, it’s an easy-going journey with minimal ups and downs once you attain the ridgelines. Approx. 630+ Ft. overall elevation gain. • Bring: Food, Water, Hiking Shoes, Walking Stick, Hat • Distance from Camp: 14 Miles /16 Min. One Way Websites of interest: • Paul Takes a Hike - Key Pictures of the trail • The Trails of NJ and NY in Pictures • Gone Hiking Blog of Lenape Ridge and Minisink Trails Logistics: Depart Camp: 12:30 pm • 12:30 pm – 1:00 pm Travel to Trailhead and prep • 1:00 pm – 4:00 pm Hike Trail (three hours to hike four miles) • 4:00 pm – 4:30 pm Return to camp Page 1 of 7 JOE 2019 Information Packet for Moderate Lenape Ridge/Minisink Trail Loop Hike (afternoon) Trail Description From the parking area, head north on a footpath, following the red blazes of the Lenape Ridge Trail and the yellow blazes of the Minisink Trail. -

This Document Does Not Meet the Current Format Guidelines of The

DISCLAIMER: This document does not meet current format guidelines Graduate School at the The University of Texas at Austin. of the It has been published for informational use only. Copyright by Jesse Harrison Ritner 2019 The Report Committee Jesse Harrison Ritner Certifies that this is the approved version of the following report: A More Perfect Nature: The Making of Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area, 15,000BP - present APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Erika Bsumek, Supervisor Robert Olwell A More Perfect Nature: The Making of Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area, 15,000BP - present by Jesse Harrison Ritner Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May, 2019 Acknowledgements I would be remiss if I did not thank Dr. Erika Bsumek for the academic and emotional support she has so kindly offered me throughout the past two years. I would also like to thank Dr. Robert Olwell for serving on my committee. iv Abstract A More Perfect Nature: The Making of Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area, 15,000BP - present Jesse Harrison Ritner, MA The University of Texas at Austin, 2019 Supervisor: Erika Bsumek This report explores the history of the Minisink Valley and the stories told about it. I examine how stories about the place influenced how people understood the past, and how these pasts were used to imagine potential futures. I pay special attention to discourses about nature as well as settler-colonial discourses. -

Upper Delaware River: Making the Connections

Upper Delaware River: Making the Connections Thank you for the support of: This document was prepared for the New York State Department of State with funds provided under Title 11 of the Environmental Protection Fund. Upper Delaware River: Making the Connections 1. Introduction 1.1. The Plan 1.2. The Stakeholders 1.3. Geography 1.3.1. The River, Three States, a Bunch of Counties and a Lot of Towns 1.3.2. Along the Roads and in the Hamlets 1.4. Natural Gas 2. Economic Development and Tourism 2.1. Introduction/Existing Conditions 2.2. Issues and Challenges 2.2.1. Lack of Lodging/Accommodations 2.2.2. Short Tourism Season 2.2.3. Other challenges identified 2.3. Opportunities and Assets 2.3.1. Get Your Feet Wet in the Upper Delaware 2.3.2. Getting Healthy 2.3.3. Finding Spirituality 2.3.4. Build Relationships 2.3.5. Watch the Birds 2.3.6. Go Fish 2.3.7. Experience History 2.3.8. Fall, Winter and Spring are also Nice Here 2.3.9. Enjoy Any One of a Number of Unique and Fun Events 2.3.10. Meet some Really Nice People 2.3.11. Become one of the Really Nice People 2.4. Vision and Strategies: Potential Projects, and Partnerships 2.4.1. Branding and Marketing 2.4.2. Developing Tools and Resources That Will Increase Access to Information and Interpretation 2.4.3. Improving Esthetics, Enhancing Identity 2.4.4. Improving the Infrastructure and Services 2.4.4.1. Internet and Cell Phone 2.4.4.2. -

The Upper Delaware Council, Inc

The quarterly nev/slettcr about the environment and people of the Upper Delavvare River ^ Vblume 12 Number 3 Published by the Upper Delaware Council, Inc. Fall 1999 In This Issue... Tusten Mountain Hiking Trail Nov/ Accessible to thc Public Pages 1 and 4 Representative Profile Marian Hrubovcak. PA DCNR UDC s Raft Trip V/cll-Reccivcd ^^^^^^^Kag^^^^^^^^B Delaware River Watershed Conference Set Nov 15-17 ^^^^^^^ Record Numbers for Sojourn. Water Monitoring on Agenda ^^^^ Rohman s Hotel Celebrates 150th Anniversary in Shohola '•mm^mm . .... t.—— UDC Awards 1999 Round of The view from the top makes the 590 vertical foot climb worthwhile on the Tusten Mountain Technical Assistance Grants Trail newiy opened to the public as a joint venturef^f the Boy Scouts of America and the National Park Service, facilitated by Town of Tusten Supervisor Dick Crandall. (Ramie Photo) P TheUppe.r DelrHvare HIkmg Tmll woicomcs submissions and Boating, fishing, swimming, camping, challenge directing folks to accessible, ' new subscribers.XfrecX' biirdwatching, biking, hunting ... the Upper dev^lbped trails.. ' Send Items to Newsletter Delaware River Valley offers a variety of The question recently became easier to 1 Editor Laurie Ramie at the I Upper Dclaviiarc Council, activities for recreation-minded visitors and answer thanks to the (areater New York 211 Bridge SL. PO. Box 192. residerits. Council of the Boy Scouts of America. •Narrovysburg. N.Y. 12764. But how about hiking? The^ Scouts entered into an agreement 1 Piease update our mailing I list by filling out the coupon i Good question. Difficult answer ^with"fSiPS in July 1999 to open the three- I on Page 7 Thank you. -

Historic Indian "Paths of Pennsylvania

Historic Indian "Paths of Pennsylvania HIS is a preliminary report. The writer is in the midst of a study of Pennsylvania's Indian trails, undertaken at the Trequest of the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Com- mission and under the special direction of S. K. Stevens, State His- torian. The examination of source materials, which are far more abundant than was supposed when the project was initiated, has not yet been completed. Much remains to be done in the field and in libraries and manuscript repositories such as The Historical Society of Pennsylvania, the American Philosophical Society, the Archives of the Moravian Church, and in the Land Office at Harrisburg, although in each of these places the writer has already spent much time. In research work of any magnitude, it is well at times to pause to get one's bearings—to see what has been accomplished, what still needs to be done, and what methods have proved themselves best to carry the work through to completion. To the writer himself, this report has already served its purpose. To others who may be inter- ested, it is hoped that its materials, incomplete though they are, may help to a better understanding of Indian trails and the events in Pennsylvania's history that depended upon them. It is impossible here to name the hundreds of persons in Pennsyl- vania, New York, Ohio, Maryland, Virginia and North Carolina who have generously assisted me in this work. It is a great fraternity, this Brotherhood of Indian Trail Followers. To them all I say, "Thank you. -

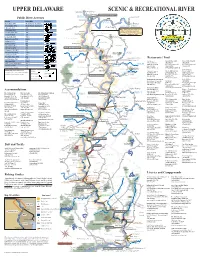

Map Inside.Pmd

UPPER DELAWARE L% SCENIC & RECREATIONAL RIVER Balls Eddy To Binghamton )"17 Hancock West Branch Hancock/Buckingham Bridge Public River Accesses Delaware River " To Downsville 17 )"30 ShehawkenL% )" ¨¦§86 HHV 10V` 1CV :H1C1 1V !( East Branch L% Delaware River :CCRR7 ^ _ V `:JH.VC:1:`V 330 Hancock (! East Branch .V.:1@VJ^ _ V `:JH.VC:1:`V (! )"17 To Roscoe )"370 Beaverkill River :JHQH@ ^_ Fishs Eddy Note: Most land within the river QH@]Q` ^ _ % ! StockportL corridor is privately owned and %H@1J$.:I^ _ 8 )"97 should be treated with due respect. Stockport Town of (Q`R01CCV^_ (! Please don't trespass or litter. 191 French Woods (QJ$RR7^_ 8 )" State Forest Preserve :@V +`VV@^_ 8 Buckingham 325 "28 ,VCC:I^_ !( ) Abe Lord Creek +:CC1HQQJ^ _ BuckinghamL% +QH.VH QJ^_ )"97 Hancock Lordville/Equinunk Bridge LordvilleL% :I:H%^ _ (!" Lordville 320 Bouchoux Trail @1JJV`/:CC^_ 8 !( Township Equinunk (! :``Q1G%`$^_ 8 ! Basket Creek Rock Valley State North Branch :`G7 Q1J^ _ 8 Forest Preserve Equinunk Creek Bouchoux Trail 1VJ21CV310V`^_ State Forest Preserve (:H@:1:6VJ^ _ 8 Long Eddy Pool Delaware County, NY Restaurants / Food ! Sullivan County, NY 1$.C:JR^_ 8 Calder House !( Long Eddy Cafe Devine * Gerard’s River Grill Nora’s Luvin’ Spoonful 315 (! Museum L% 33 Lower Main St. 251 Bridge St. 141 Kirk Rd. +Q`11J/:`I^_ 8 Long Eddy 134 Basket Creek )"191 Basket Historical UV East Branch Callicoon, NY 12723 Narrowsburg, NY 12764 Narrowsburg, NY 12764 Society 2QJ$:%]^_ L% (845) 887-3076 (845) 252-6562 (845) 252-3891 1018 Basket Creek ]:``Q1G%.^_ Manchester Township UV Crystal Lake www.cafedevine.com www.gerardsrivergrill.com Town of State Reservation Peck’s Market * CV:VQ V7QIV`:H1C1 1V :JR (! L% :`@1J$ `: .